Lfe: the Learning Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Urban Spaces Optimising Design for Comfort, Safety and Economic Vitality

Smart Urban Spaces Optimising design for comfort, safety and economic vitality Urban planners often ponder over the ways in which people will move through their designs, interact with the environment and with each other, and how best to utilise the spaces provided. Buro Happold’s Smart Space team have proven track record in optimising design of urban spaces and masterplans to enhance Capacity expansion of Makkah during Hajj visitor experience. We understand the benefits obtained from efficient layouts, intuitive wayfinding, and effective operational management. Madinah masterplan, optimising building massing to maximise shading comfort Our consultants enable a better understanding of the impacts of designs. Through the forecasting of movement and activity patterns, tailored to the specific use, our pedestrian flow modelling informs design and management in order to optimise the use of urban spaces and enhance user experience. The resulting designs are therefore extensively tested with a minimised risk of undesirable and/or unsafe congestion. We help clients better understand existing activity patterns Cardiff city centre masterplan and/or visitor preferences. With a holistic look at pedestrian and Footfall analysis of St Giles Circus, London vehicular desire lines, we can formulate a strategy to encourage footfall through the new developments. Accurate modelling provides a basis on which to assess potential risks and implement counter measures to negative factors such as poor access, fear of crime, inadequate parking facilities and lack of signage. In addition, it allows us to optimise the placement of activities – for example, placing retail in areas where the most footfall is expected; identifying appropriate spaces to locate other social activities; etc. -

Global Design Sprints: How to Reimagine Our Streets in an Era of Autonomous Vehicles

GLOBAL DESIGN SPRINTS: HOW TO REIMAGINE OUR STREETS IN AN ERA OF AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES OUTCOMES FROM CITIES AROUND THE WORLD URBAN STREETS IN THE AGE OF AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES CONTENTS - 2017 - GLOBAL DESING SPRINT OUTCOMES 2 Global Design Sprints - 2017 URBAN STREETS IN THE AGE OF AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES 1. INTRODUCTION Technological advancement for autonomous vehicles accelerated in 2015 Using this format, we hosted a series of global events to speculate and The following report is the result of this series of Global Design Sprints and, suddenly, everyone was talking about a future of autonomous and brainstorm the question of : – a collaboration of 138 sprinters from across the world. The executive connected vehicles. At BuroHappold, we wanted to understand what summary compares the different discussions and outcomes of the Sprints it might mean for our cities. How will our cities be impacted? Will there ‘HOW CAN URBAN STREETS BE RECLAIMED AND REIMAGINED and summarizes some of the key takeaways we collected. The ideas that be more or less traffic? Which ownership model for autonomous and THROUGH THE INTRODUCTION OF CONNECTED AND emerged range from transforming a residential neighbourhood from a car- connected vehicles will prevail? These are questions that many have asked, AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES?‘ zone to a care-zone to the introduction of the flexible use of a road bridge but no one can really answer today – even with the most sophisticated based on the demand from commuters, tourists, cyclists, and vehicular forecasting models. We cannot predict how people will respond to such a By bringing together people from the technology sector, the urban traffic. -

Read the SPUR 2012-2013 Annual Report

2012–2013 Ideas and action Annual Report for a better city For the first time in history, the majority of the world’s population resides in cities. And by 2050, more than 75 percent of us will call cities home. SPUR works to make the major cities of the Bay Area as livable and sustainable as possible. Great urban places, like San Francisco’s Dolores Park playground, bring people together from all walks of life. 2 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 3 It will determine our access to economic opportunity, our impact on the planetary climate — and the climate’s impact on us. If we organize them the right way, cities can become the solution to the problems of our time. We are hard at work retrofitting our transportation infrastructure to support the needs of tomorrow. Shown here: the new Transbay Transit Center, now under construction. 4 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 5 Cities are places of collective action. They are where we invent new business ideas, new art forms and new movements for social change. Cities foster innovation of all kinds. Pictured here: SPUR and local partner groups conduct a day- long experiment to activate a key intersection in San Francisco’s Mid-Market neighborhood. 6 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 SPUR Annual Report 2012–13 7 We have the resources, the diversity of perspectives and the civic values to pioneer a new model for the American city — one that moves toward carbon neutrality while embracing a shared prosperity. -

Delivering Building Performance

MAY 2016 Full Report DELIVERING BUILDING PERFORMANCE With thanks to sponsors: © 2016 UK Green Building Council Registered charity number 1135153 Delivering Building Performance | 1 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 2 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 7 Overcoming barriers to delivering building performance 9 Conclusion 28 C-Suite Headlines 30 References 32 Delivering Building Performance | 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PROJECT STEERING GROUP Project steering group: ■ Julian Sutherland, Cundall (formerly Atkins): Project Chair ■ Lynne Ceeney, Lytton Consulting: Project Manager on behalf of UK-GBC ■ Chris van Dronkelaar, BuroHappold/UCL: Project Researcher ■ Mark Allen, Saint Gobain ■ John Davies, Derwent London ■ Emma Hines, Tarmac ■ Judit Kimpian, AHR ■ Duncan Price, BuroHappold ■ Sarah Ratcliffe, Better Buildings Partnership UK-GBC is grateful to project sponsors, Buro Happold, Saint Gobain and Tarmac. INTERVIEWEES Interviewees were drawn from the following sectors: Investors, developers, owner occupiers, leasing occupiers, managing agents, facilities managers, professional services, manufacturers and membership organisations. We would like to specifically thank: ■ BRE (Andy Lewry) ■ Canary Wharf Group (Dave Hodge, Rita Margarido and Lugano Kapembwa) ■ The Crown Estate (Jane Wakiwaka) ■ Derwent London (John Davies) ■ Hoare Lea (Julie Godefroy) ■ IES (Sarah Graham and Naghman Khan) ■ John Lewis Partnership (Phil Birch) ■ Land Securities (Caroline Hill and Neil Pennell) ■ Legal and General (Debbie Hobbs) ■ Lend Lease (Hannah Kershaw) ■ Marks and Spencer (Kate Neale) ■ M J Mapp (Carl Brooks) ■ Tarmac (Tim Cowling) ■ UPP (James Sandie) ■ Wilkinson Eyre (Gary Clark) ■ Participants in the UK-GBC seminar at Ecobuild ■ Participants in the Edge seminar at Ecobuild Executive Summary Delivering Building Performance | 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The performance in operation, of the vast majority of our buildings, is simply not commensurate with the challenge of meeting our carbon targets. -

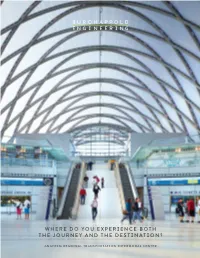

Where Do You Experience Both the Journey and the Destination?

WHERE DO YOU EXPERIENCE BOTH THE JOURNEY AND THE DESTINATION? ANAHEIM REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION INTERMODAL CENTER SMARTER FASTER I NTEGRATED SOLUTIONS FOR CIVIC ARCHITECTURE VISION To catalyze transit-oriented growth, Orange County envisioned a world-class gateway linking regional transportation systems, providing convenient access to the area’s renowned destinations, and offering distinctive restaurants, shops and events. The iconic, LEED Platinum landmark embodies the region’s commitment to a vital, sustainable future. CHALLENGE As a modern multi-modal transportation hub designed to connect eight existing public and private transportation systems as well as future streetcar and high-speed rail lines, ARTIC involved extensive coordination of complex infrastructure. When combined with aggressive sustainability targets— including 30% reduction of both energy and water use—and the desire for a landmark design, the project demanded a fully integrated design solution to achieve project goals within budget tolerances. SOLUTION Taking a holistic design approach using BIM and advanced computational design and analysis tools allowed the design team to propose a complex catenary-shaped enclosure employing lightweight ETFE panels. In addition to optimizing the design for energy performance and constructability, the models facilitated cost estimating, construction sequencing, just-in-time ordering, and digital fabrication. VALUE The integrated solution leveraged the ETFE enclosure to address multiple goals. The translucent and insulating panels with varied frit patterns maximized daylight while reducing solar heat gain. Equally important, at just one-tenth the weight of glass, these lightweight panels required a less costly steel support structure. The modeling also enabled strategies for natural ventilation and water recycling that will reduce resource consumption and operating costs over time. -

Design Checks for Electrical Services

A BSRIA Guide www.bsria.co.uk Design Checks for Electrical Services A quality control framework for electrical engineers By Kevin Pennycook Supported by BG 3/2006 Design considerations Design issues Calculations Systems and equipment PREFACE Donald Leeper OBE The publication of Design Checks for Electrical Services is a welcome addition to the well received and highly acclaimed Design Checks for HVAC, published in 2002. The design guidance sheets provide information on design inputs, outputs and practical watch points for key building services design topics. The guidance given complements that in CIBSE Guide K, Electricity in Buildings, and is presented in a format that can be easily incorporated into a firm’s quality assurance procedures. From personal experience I have seen the benefit of such quality procedures. Once embedded within a process information management system, the guidance in this book will ensure consistent and high quality design information. When used for validation and verification, the design checks and procedures can also make a key contribution to a risk management strategy. The easy-to-follow layout and the breadth of content makes Design Checks for Electrical Services a key document for all building services engineers. Donald Leeper OBE President, CIBSE 2005-06 Consultant, Zisman Bowyer and Partners LLP DESIGN CHECKS FOR ELECTRICAL SERVICES © BSRIA BG 3/2006 Design considerations Design issues Calculations Systems and equipment ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS BSRIA would like to thank the following sponsors for their contributions to this application guide: Griffiths and Armour Professional Risk hurleypalmerflatt Atkins Consultants Limited Mott MacDonald Limited Faber Maunsell EMCOR Group (UK) plc Bovis Lend Lease Limited The project was undertaken under the guidance of an industry steering group. -

• Annual Revie%

Nor — 1.3 , • ' +. • /1 111W • • " 1.74, - Amp --"P= ' • k 1 • - • -4 st :.i;, ' „ , •-• Engineers Without Borders U14 I t. , 4 Annual Revie% September 2005 - August 200( te o f IL)ridge anchor in rural Malawi supported by an EWE3,-UK bursary [Daniel Carrkvic Mission To facilitate human development through engineering. Introduction Aims • To educate and raise awareness of students and others about issues in Annual Review human development; * to promote research related to, and actively contribute towards, engineering Engineers Without Borders UK is a student-run charity whose focus is on technical solutions for human development; contributions to international development. This report summarises our main • provide an ongoing supply of competent and knowledgeable professional activities for the academic year from September 2005 to August 2006. development workers, and; • to become a mark of excellence for those looking to become involved with The highlights are reported by our members, branch committee members and development work. core co-ordinators in the following sections: 1 - Introduction: Mission and Chief Executives' Summary Approach 3 - Our Team: EWB-UK Core Team, Trustees, Branches and Professional Network • Training and educating students and recent graduates in development theory 7 - Training and practice; 8 - Awareness: Events, Publicity and Education • using student volunteers and academics to undertake research; 9 - Placements • making use of professional volunteers to support our work; 11 - Research • providing suitable -

Buro Happold

Buro Happold Buro Happold Our distinctive culture and philosophy is based on the principles care, value and of elegance Bath Belfast Birmingham Edinburgh Glasgow Berlin Leeds Copenhagen London Milan Manchester Moscow Munich Warsaw New York Boston Chicago San Francisco Beijing Los Angeles Honk Kong Mumbai Abu Dhabi Cairo Dubai Jeddah Kuwait Riyadh 12 countries, 28 offices, 1500 people US Office Offices: Services: Buro Happold est’b. 1999 Boston, New York, Structural Engineering Chicago, Los Angeles, Designing US Bridge Engineering and San Francisco projects since MEP Engineering 1980s Staff: 200 Environmental Consulting Special Structures Awards Select Clients • American Council of • Friends of the HighLine Sustainability Engineering • Harvard University Companies Façade Design • Walton Foundation • American Institute of Lighting Architects • Lyme Properties • American Institute of • Smithsonian Institution Simulation Analysis Steel Construction • City of New York • City of New York • Safdie Architects Fire Engineering • ENR/New York • FXFowle Architects • Master Planning Aga Khan Award for • US GSA Architecture • SL Green Realty Code & Accessibility • National Council of Structural Engineers Corporation • NY State Society of • New Doha International Professional Airport Engineers • Battery Park City Authority Buro Happold North America Buro Happold FACADES STRUCTURAL SUSTAINABILITY LIGHTING ENERGY & MEP INFRASTRUCTURE FIRE & LIFE SAFETY MASTER PLANNING Interdisciplinary makes a difference Office est’b. Offices: Services: Buro Happold 2002 -

Enginuity 2017 Competition TEAM IMPROVEMENT TABLE

Enginuity 2017 Competition TEAM IMPROVEMENT TABLE During period 10 (Early Years) Position Name Sponsor Location Imp rovement 1 The Transatlantic Trade Union Steer Davies Gleave Colombia 21 % 2 Mouchel Scousers WSP UK 19 % 3 Geotopia WSP UK 18 % 4 Prestige Worldwide WSP United States 14 % 5 Taken For Granite Arcadis UK 12 % 6 Le Nain Rouge WSP United States 12 % 7 JaCUB's Builders Jacobs Ireland 11 % 8 Make New Zealand Great Again OPUS International Consultants New Zealand 11 % 9 Global Construction WSP Qatar 11 % 10 The Business Campaigner WSP Qatar 11 % 11 GDL Rail WSP UK 11 % 12 Build Everything Create Anything Beca New Zealand 10 % 13 Making Work Holistic, now part of Enginuity MWH now part of Stantec UK 10 % 14 Creepy Crawleys UK Power Networks UK 10 % 15 Southerners WSP UK 10 % 16 JuMEngi WSP UK 10 % 17 The Brummies WSP UK 10 % 18 TheBestBecaTeamSoFar Beca New Zealand 9 % 19 Bechtel-ligence Bechtel UK 9 % 20 Green is the New Black Cundall UK 9 % 21 FNGenius Mott Macdonald UK 9 % 22 FMAC Construction Mott Macdonald UK 9 % 23 Never Tell Me The Odds WSP United States 9 % 24 Exe-Men WSP UK 9 % 25 CH2Much CH2M UK 8 % 26 #Hatchtag_winning Hatch Canada 8 % 27 Pa-shock Independent UK 8 % 28 Motts Water Warriors Mott Macdonald UK 8 % 29 Magnitude Management OPUS International Consultants New Zealand 8 % 30 Robert's Lucky Birds Robert Bird Group UK 8 % 31 Synergy WSP United States 8 % 32 Unleash the CampbellReith Campbell Reith Hill LLP UK 7 % 33 Cundallicious Cundall UK 7 % 34 JAPK MWH now part of Stantec Taiwan 7 % 35 IJC Ltd MWH now part -

Awards and Recognition Banquet

14th Annual Architectural Engineering AWARDS AND RECOGNITION BANQUET Thursday, February 28, 2019 Scott Conference Center - Omaha, NE Learn Today Build Tomorrow WELCOME Dear Alumni, Industry Partners, Students and Friends: It is my pleasure to welcome you to our Annual Durham School Architectural Engineering Awards Banquet. I am in my fourth year as Director of The Durham School, and during this time, I have grown to appreciate our outstanding AE program and the many exceptional, national-level achievements of our students and our faculty. The collaboration and support of industry is simply amazing! Let me take this important opportunity to say Thank You. In consultation with all stakeholders, we are strategically planning to set our agenda for the coming years. Industry collaboration is a hallmark of our School and will continue to be integral in all aspects of our instructional and research missions. Architectural Engineering and Construction has a huge footprint in Nebraska, and we will continue to engage our partners to provide a sustained, well-educated workforce who is innovative, yet practical and solution-oriented. University and College leadership is committed to helping The Durham School offer the best architectural engineering program in the nation. This includes expanding the number of graduates to meet the ever-increasing industry demand, increasing our outreach activities to a national level, taking the lead as the producer of AE faculty through a quality Ph.D. program, training the professoriate nationally in teaching and learning, and offering research programs that are making a difference in the AEC industry. We are continuously updating our curriculum to ensure our students are learning the most current technologies as related to their field, while never losing sight of the fundamentals. -

St Catherine and Firwood Academy

Client St Catherine and Firwood Academy Borough Council of Bolton Lead Designer Sheppard Robson Value £35.1M Contract Period 104 Contract Form Partnership for Schools Bespoke Type of Work New Build Kier St Catherine's and Firwood Academy in Bolton is the country's first 'superschool'. It has been built in the grounds of the existing school which was in use and demolished upon completion of the new school. The new Academy accommodates up to 1286 students aged 2-19 years and are developed holistically by including a one form entry primary school to replace an existing nearby school within the academy. The Academy provides 26 nursery places for ages 3-5, 210 places for students aged 5-11, 750 (5FE) places for students aged 11-16, 100 places for students aged 11-16 in the special school, and 200 post- 16 places. The Academy specialise in Mathematics and computing and business and enterprise. The full service campus will extend its links to partners in the business world to ensure that the curriculum provides experienced based learning. This supports the development of an enterprise culture for the students and gives them direct experience of the working environment. The Campus will be the biggest centre for employment in the local community and its integrated provision will support the medical, social and human services essential to meet the wider needs of children, young people and their families as well as in education. Client Benefits The provision of a new Academy incorporating Junior, Primary, Secondary and 6th form provision. The academy has also incorporated a Special Needs School with provision of up to 120 places. -

Annual Review Contents

18 /19 ANNUAL REVIEW CONTENTS WELCOME CHIEF EXECUTIVE SENIOR CHIEF OPERATING AND OFFICER PARTNER FINANCIAL OFFICER Neil Squibbs Paul Rogers James Bruce 6 10 14 SPECIALISTS CAROLINA FLORIAN Associate Lighting Designer 28 DAVOOD LIAGHAT Head of Bridge Engineering and Civil Structures 46 CHARIS COSMAS Associate Facades Engineer 54 COVER The south stand “trees” at Tottenham Hotspur stadium in London. BUROHAPPOLD 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS SECTORS FEATURES Image: NASA Image: SPORT AND CLIMATE TECHNOLOGY COMMUNITIES PEOPLE ENTERTAINMENT Engineers versus carbon How digital innovation Mass housing design that Why everyone benefits 22 in the race to avert global is enabling exceptional improves quality from our inclusive culture environmental disaster. outcomes. of life. and progressive approach. 18 36 62 72 COMMERCIAL 30 CULTURAL 40 DETAILS SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 48 BEYOND ENGINEERING Stories from around the practice. AIR AND RAIL 82 56 FINANCIAL URBAN INFORMATION DEVELOPMENT The year in figures. 66 90 EDUCATION THE LAST WORD Sir Ted Happold. 76 98 4 ANNUAL REVIEW 18/19 BUROHAPPOLD 5 NEIL SQUIBBS CEO INTRODUCTION We will always strive to deliver solutions with a sense of economy for our inding solutions is what we This might inform a design solution. planet and its do. What we at BuroHappold Perhaps an alternative solution that resources. know is that the solution to doesn’t require construction or other a particular problem does intervention might be the answer. not come fully formed. Using all the tools at our disposal, our Consultancy is about making that Fpeople examine each issue from every technical expertise accessible. Our angle before arriving at an answer.