Milton Keynes Trail

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

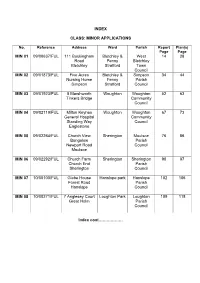

Index Class: Minor Applications Min 01 09/00637

INDEX CLASS: MINOR APPLICATIONS No. Reference Address Ward Parish Report Plan(s) Page Page MIN 01 09/00637/FUL 111 Buckingham Bletchley & West 14 28 Road Fenny Bletchley Bletchley Stratford Town Council MIN 02 09/01873/FUL Five Acres Bletchley & Simpson 34 44 Nursing Home Fenny Parish Simpson Stratford Council MIN 03 09/01923/FUL 8 Marshworth Woughton Woughton 52 63 Tinkers Bridge Community Council MIN 04 09/02119/FUL Milton Keynes Woughton Woughton 67 73 General Hospital Community Standing Way Council Eaglestone MIN 05 09/02264/FUL Church View Sherington Moulsoe 76 86 Bungalow Parish Newport Road Council Moulsoe MIN 06 09/02292/FUL Church Farm Sherington Sherington 90 97 Church End Parish Sherington Council MIN 07 10/00100/FUL Glebe House Hanslope park Hanslope 102 106 Forest Road Parish Hanslope Council MIN 08 10/00271/FUL 7 Anglesey Court Loughton Park Loughton 109 118 Great Holm Parish Council Index cont……………… CLASS: OTHER APPLICATIONS No. Reference Address Ward Parish Report Plan(s) Page Page OTH 01 09/01872/FUL 1 Rose Cottages Wolverton Wolverton & 122 130 Mill End Greenleys Wolverton Mill Town Council OTH 02 09/01907/FUL 6 Twyford Lane Walton park Walton 135 140 Walnut Tree parish Council OTH 03 09/02161/FUL 16 Stanbridge Stony Stony 143 148 Court Stratford Stratford Stony Stratford Town Council OTH 04 09/02217/FUL 220A Wolverton Linford North Great Linford 152 159 Road Parish Blakelands Council OTH 05 10/00117/FUL 98 High Street Olney Olney Town 162 166 Olney Council OTH 06 10/00049/FUL 63 Wolverton Newport Newport 168 174 Road Pagnell North Pagnell Newport Pagnell Town Council OTH 07 10/00056/FUL 24 Sitwell Close Newport Newport 177 182 Newport Pagnell Pagnell North Pagnell Town Council CLASS: OTHER APPLICATIONS – HOUSES IN MULTIPLE OCCUPATION No. -

Milton Keynes' Parks a Guide to Event & Filming Locations

Milton Keynes’ Parks A guide to event & filming locations The parks are ideal places to hold an event, from community picnics to large concerts and festivals or to use for a filming or photographic project. We welcome requests from groups and organisations to organise their own events and activities in the parks in Milton Keynes. This guide has been written as a guide to choosing our parks for an event or filming location. [email protected] 01908 233600 Contents 1. Introduction 2. Map 3. Parks / Venues 4. Campbell Park 5. Willen Lake North 6. Willen Lake South 7. Furzton Lake 8. Caldecotte Lake 9. Linford Manor Park 10. Tree Cathedral 11. Concrete Cows 12. Using our parks for filming purposes Introduction The parks are ideal places to host your own event from community picnics to festivals or for filming opportunities. We welcome requests from groups and organisations to organise their own events and activities in the parks in Milton Keynes. Many regional and national events have taken place in our parkland making Milton Keynes a great location. It has good road and rail links, being just 30 minutes rail journey from Birmingham and London, with major road links M1 and A5 flowing through the city. Due to the unique makeup of Milton Keynes the parkland areas available for events or filming range from a large central city park to lakes and woodland and are suitable for many different occasions. Recommended parkland areas include: • Campbell Park • Willen Lake North • Willen Lake South • Furzton Lake • Caldecotte Lake • Great Linford Manor Park • Tree Cathedral • Concrete Cows (photos/filming only) • Roman Villa, Bancroft (Suitable for small events only) • Millfield (Suitable for small events only) Within this guide each recommended parkland area has a dedicated page explaining valuable information and statistics. -

CAMPBELL PARK, MILTON KEYNES AMENDED August 2018

Understanding Historic Parks and Gardens in Buckinghamshire The Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust Research & Recording Project CAMPBELL PARK, MILTON KEYNES AMENDED August 2018 The Stanley Smith (UK) Horticultural Trust Bucks Gardens Trust HISTORIC SITE BOUNDARY NB the south-west corner of Campbell Park (the environs of Marlborough Street) overlaps with part of the north-east corner of Central Milton Keynes (qv). Bucks Gardens Trust, Site Dossier: Campbell Park, Milton Keynes, MKC A 2018 NB the south-west corner of Campbell Park (the environs of Marlborough Street) overlaps with part of the north-east corner of Central Milton Keynes (qv). 2 INTRODUCTION Background to the Project This site dossier has been prepared as part of The Buckinghamshire Gardens Trust (BGT) Research and Recording Project, begun in 2014. This site is one of several hundred designed landscapes county-wide identified by Bucks County Council (BCC) in 1998 (including Milton Keynes District) as potentially retaining evidence of historic interest, as part of the Historic Parks and Gardens Register Review project carried out for English Heritage (now Historic England) (BCC Report No. 508). The list is not definitive and further parks and gardens may be identified as research continues or further information comes to light. Content BGT has taken the Register Review list as a sound basis from which to select sites for appraisal as part of its Research and Recording Project for designed landscapes in the historic county of Bucks (pre-1974 boundaries). For each site a dossier is prepared by volunteers trained on behalf of BGT by experts in appraising designed landscapes who have worked extensively for English Heritage/Historic England on its Register Upgrade Project. -

Campbell Wharf

CAMPBELL WHARF MILTON KEYNES For a taste of city living, enjoying the ever-changing colours of the seasons, the tranquillity of the canal and the sound and feel of nature – Campbell Wharf is for every side of life. 1 - 5 BEDROOM HOMES JOB NUMBER TITLE PG VERSION DATE Size at 100% CR LOCAL AREA INSERT 1 A4P DESIGNER Org A/W A/W AMENDS C: DATE: CAMPBELL WHARF AROUND THE AREA WELCOME TO LIFE IN CAMPBELL WHARF T R IC Based in the heart of Milton Keynes, enjoy green spaces, shops, cafés K F O 4 R D S T and a 111-berth marina in a much sought-after location in the city. R E E T On your doorstep Education Travel Featuring a wide range of amenities all Your new home at Campbell Wharf is Well positioned whether you’re working within easy reach of Campbell Wharf, surrounded by a range of schools, so locally or commuting. London, Birmingham Milton Keynes has two shopping centres, your children have lots of options for the and other major cities are easy to reach, M1 a range of nightlife, activities and best start and continuation of their and there are lots of local attractions within entertainment, all surrounded by green education. a few minutes reach of your doorstep. L space, to give a balance to your quality O N D of life. O 13 N Asquith Court School R O Centre MK – 2 minutes A D 14 Giggles at Down Barns Pre School 1 Garden Square Campbell Park – 3 minutes AY S W 15 NK Downs Barn Infant School Xscape Entertainment Complex – 3 minutes MO 2 Canal Square H3 Intu Milton Keynes – 22 minutes 16 Oldbrook First School 3 Canalside Pub 17 Southwood Schoovl -

8 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

8 bus time schedule & line map 8 Central Milton Keynes View In Website Mode The 8 bus line (Central Milton Keynes) has 6 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Central Milton Keynes: 10:52 PM (2) Oxley Park: 6:03 AM - 9:52 PM (3) Walnut Tree: 6:08 AM - 10:10 PM (4) Wavendon Gate: 6:43 PM (5) Westcroft: 7:22 PM - 10:42 PM (6) Westcroft: 6:35 PM - 8:52 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 8 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 8 bus arriving. Direction: Central Milton Keynes 8 bus Time Schedule 25 stops Central Milton Keynes Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 10:52 PM Walton High School, Walnut Tree Tuesday 10:52 PM Lichƒeld Down, Walnut Tree 146 Lichƒeld Down, Milton Keynes Wednesday 10:52 PM Bourton Low, Walnut Tree Thursday 10:52 PM Bourton Low, Milton Keynes Friday 10:52 PM Elgar Grove, Browns Wood Saturday 10:52 PM 22 Elgar Grove, Milton Keynes Hindmithe Gardens, Old Farm Park Britten Grove, Milton Keynes 8 bus Info Byrd Crescent, Wavendon Gate Direction: Central Milton Keynes 32 Gable Thorne, Milton Keynes Stops: 25 Trip Duration: 36 min Gregories Drive, Wavendon Gate Line Summary: Walton High School, Walnut Tree, Gregories Drive, Milton Keynes Lichƒeld Down, Walnut Tree, Bourton Low, Walnut Tree, Elgar Grove, Browns Wood, Hindmithe Gardens, Dixie Lane, Wavendon Gate Old Farm Park, Byrd Crescent, Wavendon Gate, Gregories Drive, Wavendon Gate, Dixie Lane, Walton High School, Walnut Tree Wavendon Gate, Walton High School, Walnut Tree, Walnut Tree Roundabout South, -

Updated Electorate Proforma 11Oct2012

Electoral data 2012 2018 Using this sheet: Number of councillors: 51 51 Fill in the cells for each polling district. Please make sure that the names of each parish, parish ward and unitary ward are Overall electorate: 178,504 190,468 correct and consistant. Check your data in the cells to the right. Average electorate per cllr: 3,500 3,735 Polling Electorate Electorate Number of Electorate Variance Electorate Description of area Parish Parish ward Unitary ward Name of unitary ward Variance 2018 district 2012 2018 cllrs per ward 2012 2012 2018 Bletchley & Fenny 3 10,385 -1% 11,373 2% Stratford Bradwell 3 9,048 -14% 8,658 -23% Campbell Park 3 10,658 2% 10,865 -3% Danesborough 1 3,684 5% 4,581 23% Denbigh 2 5,953 -15% 5,768 -23% Eaton Manor 2 5,976 -15% 6,661 -11% AA Church Green West Bletchley Church Green Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1872 2,032 Emerson Valley 3 12,269 17% 14,527 30% AB Denbigh Saints West Bletchley Saints Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1292 1,297 Furzton 2 6,511 -7% 6,378 -15% AC Denbigh Poets West Bletchley Poets Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1334 1,338 Hanslope Park 1 4,139 18% 4,992 34% AD Central Bletchley Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Central Bletchley Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 2361 2,367 Linford North 2 6,700 -4% 6,371 -15% AE Simpson Simpson & Ashland Simpson Village Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 495 497 Linford South 2 7,067 1% 7,635 2% AF Fenny Stratford Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Fenny Stratford Bletchley & Fenny Stratford 1747 2,181 Loughton Park 3 12,577 20% 14,136 26% AG Granby Bletchley & Fenny Stratford Granby Bletchley -

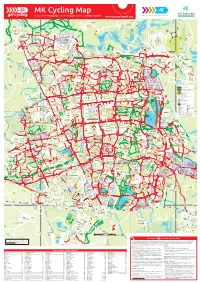

MK Cycling Map a Map of the Redways and Other Cycle Routes in Milton Keynes

MK Cycling Map A map of the Redways and other cycle routes in Milton Keynes www.getcyclingmk.org Stony Stratford A B C Little D Riv E Linford er Great O Nature Haversham Dovecote use Reserve Ouse Valley Park Spinney Qu e W en The H Grand Union Canal a A5 Serpentine te i E r g le L h a se Haversham a n u S Riv t O ne o er Grea Village School t r r e S e tr Burnt t e et Covert Sherington Little M Russell Linford 1 Stony Stratford Street Ouse Valley Park Park L Library i School St Mary and St Giles t t Lakelane l Ousebank C of E Junior School Co e lt L Spinney WOLVERTON s H i ol n m f MILL Road o Old W r Wolverton Ro olv Manor d ad Strat Tr ert ford Road on L ad i R Farm a Lathbury o n oad n R Slated Row i e n t t y Ouse Valley Park to STONY e School g R n e i o r r t Stantonbury STRATFORD a OLD WOLVERTON Haversham e L d h o S Lake y S n r Lake a d o W o n WOLVERTON MILL W d n Portfields e Lathbury a s e lea EAST W s R S s o E Primary School t House s tr R oa at e b C n fo r o hi u e r u ch n e d c rd ele o d The R r O rt u o y swo y H e Q ad n r y il t Radcliffe t l lv R h 1 a i n Lan 1 e v e e Ca School Wolverton A r er P r G Gr v L e eat e v Wyvern Ou a i n R M se Bury Field l A u k il d School l L e e i H din i l y gt a t s f le on A t al WOLVERTON MILL l o n e e G ve C Wolverton L r h G u a L a d venu Queen Eleanor rc i A SOUTH r h Library n n S C Primary School e A tr R Blackhorse fo e H1 at M y ee d - le t iv n r a y sb e Stanton REDHOUSE d o a u r Bradwell o Lake g d R r V6 G i a L ew y The r n Newport n n o g o e Low Park PARK a -

Cast Your Vote! Have Your Say! REFERENDUM See Page 3

ISSUE: AUTUMN 2018 Homeground THE MAGAZINE FROM THE MAGAZINE FROM Campbell Park Parish Council WILLEN WINTERHILL OLDBROOK FISHERMEAD SPRINGFIELD NEWLANDS WOOLSTONE The Mayor will be casting his vote Cast your vote! Have your say! REFERENDUM see page 3 CAMPBELL PARK PARISH COUNCIL Caring within the community CAMPBELL PARK PARISH COUNCIL OFFICE HOURS: 1 Pencarrow Place, Fishermead, Milton Keynes MK6 2AS 10am - 4pm Monday to Thursday T 01908 608559 10am - 3pm on a Friday Ward Members of CAMPBELL PARK PARISH COUNCIL Campbell Park Parish Council serves nearly 6,000 households in Fishermead, Oldbrook, Springfield, Willen and Woolstone, the leisure area of Newlands and the retail area of Winterhill. OLDBROOK VACANT SEAT KATHERINE KENT TOM FRASER VICE CHAIR LARRY HARRIS TUBO URANTA ELAINE DICERBO 01908 331935 01908 607033 BRIAN GREENWOOD 01908 675766 01908 982626 07885 518252 07956 384000 FISHERMEAD CHAIR OF COUNCIL PENELOPE DARRON MARTIN DAVID PRIEST TERRY BAINES HALTON-DAVIS KENDRICK PETCHEY 07508 312412 07846 697237 01908 696034 01908 669067 01908 605488 07712 485255 WILLEN SPRINGFIELD WOOLSTONE VACANT SEAT VACANT SEAT ADAN KAHIN NANA OGUNTOLA CHRIS BROWN DAVID PAFFORD 01908 608559 07949 335822 01908 608559 01908 608559 Staff CAMPBELL PARK PARISH COUNCIL CLERK TO COUNCIL DEPUTY CLERK COMMUNITY OFFICER/ ENVIRONMENT OFFICERS FINANCE OFFICER P/TIME ADMIN ASSISTANT P/TIME DOMINIC WARNER ELAINE WEBB COMMITTEE CLERK P/TIME JOHN McLINTON LISA BRADLEY TRACEY WAISTNEDGE TRACEY JONES MITCH MITCHENER HOW TO CONTACT US OFFICE OPENING HOURS HOW TO CONTACT -

FRIDAY 10TH - SUNDAY 12TH MAY 2019 a Variety of Walks Across Three Days for All Ages and Abilities

WALKING FESTIVAL FRIDAY 10TH - SUNDAY 12TH MAY 2019 A variety of walks across three days for all ages and abilities Wondering where to walk now? If you’re feeling inspired after joining us for our Walking Festival, don’t stop now as there are many ways to keep walking in Milton Keynes. We organise a range of walks across the city, both during the week and at weekends, for people of all ages and abilities. Alternatively, a selection of self-guided walks can be downloaded from our website, including our 25-mile Challenge Walk. For more information: Visit: www.theparkstrust.com Email: [email protected] Call: 01908 255379 theparkstrust @theparkstrust theparkstrust Welcome DATE AND TIME: Fri 10 May 2019, 10:00am WALK TITLE: WILLEN HOSPICE WALK WALK DESCRIPTION: Take a walk by Willen Lake with the company and support of the Willen Hospice Walking Team. Come prepared for countryside walking and uneven paths. This walk Walk 1 will be at a gentle pace. Tea and coffee will be available after completing the walk. WALK LENGTH: 1 hour. GRADING: LOCATION: Willen Lake North. MEETING POINT/PA RKING: Meet at The Wellbeing Centre, Community Hub entrance via car park 2 at Willen Hospice, Milton Road, MK15 9AB. COST: Free. BOOKING INFORMATION: Booking essential. Book online at www.theparkstrust.com For further information please contact: [email protected] 01908 255379. DATE AND TIME: Fri 10 May 2019, 9:00pm WALK TITLE: BAT WALK WALK DESCRIPTION: Take a walk with local bat enthusiasts and discover these fascinating nocturnal Walk 2 creatures. Come prepared for countryside walking and uneven paths. -

Castlethorpe Neighbourhood Plan Referendum – 22Nd July 2021 General Information for Voters

Castlethorpe Neighbourhood Plan Referendum – 22nd July 2021 General Information for voters About this document On 22nd July 2021 there will be a referendum for residents in Castlethorpe parish on the Castlethorpe Neighbourhood Plan. The Castlethorpe Parish Council has prepared the Neighbourhood Plan for its parish and it has been agreed that the referendum area will cover the whole parish area. This document explains more about the referendum that is going to take place and how you can take part. It also gives you information about the Town and Country Planning system. The Referendum The referendum on 22nd July 2021 will ask you to vote ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a question. For this referendum you will receive a ballot paper with this question: “Do you want Milton Keynes Council to use the Neighbourhood Plan for Castlethorpe to help it decide planning applications in the neighbourhood area?” How do I vote in the referendum? You show your choice by putting a cross (X) in the ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ box on your ballot paper. Put a cross in only one box or your vote will not be counted. If the referendum comes out in favour of the Neighbourhood Plan it will be adopted, and if adopted, the Neighbourhood Plan will become part of the Development Plan. The Town and Country Planning System The planning system helps to decide what gets built, where and when. It is essential for supporting economic growth, improving people’s quality of life, and protecting the natural and historic environment. Most new buildings, major changes to existing buildings or major changes to the local environment need planning permission. -

Milton Keynes Councillors

LIST OF CONSULTEES A copy of the Draft Telecommunications Systems Policy document was forwarded to each of the following: MILTON KEYNES COUNCILLORS Paul Bartlett (Stony Stratford) Jan Lloyd (Eaton Manor) Brian Barton (Bradwell) Nigel Long (Woughton) Kenneth Beeley (Fenny Stratford) Graham Mabbutt (Olney) Robert Benning (Linford North) Douglas McCall (Newport Pagnell Roger Bristow (Furzton) South) Stuart Burke (Emerson Valley) Norman Miles (Wolverton) Stephen Clark (Olney) John Monk (Linford South) Martin Clarke (Bradwell) Brian Morsley (Stantonbury) George Conchie (Loughton Park) Derek Newcombe (Walton Park) Stephen Coventry (Woughton) Ian Nuttall (Walton Park) Paul Day (Wolverton) Michael O’Sullivan (Loughton Park) Reginald Edwards (Eaton Manor) Michael Pendry (Stony Stratford) John Ellis (Ouse Valley) Alan Pugh (Linford North) John Fairweather (Campbell Park) Christopher Pym (Walton Park) Brian Gibbs (Loughton Park) Hilary Saunders (Wolverton) Grant Gillingham (Fenny Stratford) Patricia Seymour (Sherington) Bruce Hardwick (Newport Pagnell Valerie Squires (Whaddon) North) Paul Stanyer (Furzton) William Harnett (Denbigh) Wedgwood Swepston (Emerson Euan Henderson (Newport Pagnell Valley) North) Cec Tallack (Campbell Park) Irene Henderson (Newport Pagnell Bert Tapp (Hanslope Park) South) Christine Tilley (Linford South) David Hopkins (Danesborough) Camilla Turnbull (Whaddon) Janet Irons (Bradwell Abbey) Paul White (Danesborough) Harry Kilkenny (Stantonbury) Isobel Wilson (Campbell Park) Michael Legg (Denbigh) Kevin Wilson (Woughton) David -

Campbell Park Northside Development Brief Proposed Amendments

ANNEX B Urban Design & Landscape Architecture Campbell Park Northside Development Brief Proposed Amendments www.milton-keynes.gov.uk/udla February 2018 Campbell Park Northside Development Brief: Proposed Amendments This document has been prepared by Milton Keynes Council’s Urban Design and Landscape Architecture Team. For further information please contact: Neil Sainsbury, Head of Placemaking Growth, Economy and Culture Milton Keynes Council PO Box 113, Civic Offices 1 Saxon Gate East Milton Keynes, MK9 3HN T +44 (0) 1908 252708 F +44 (0) 1908 252329 E [email protected] 2 Urban Design & Landscape Architecture Contents SECTION 1 INTRODUCTION SECTION 3 CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS SECTION 5 DEVELOPMENT AND DESIGN PRINCIPLES 5.1 Introduction pg33 1.1 Introduction pg05 3.1 Introduction pg19 5.2 Layout pg33 1.2 Purpose of Development Brief pg06 3.2 Surrounding Area pg19 5.3 Key Frontages and Buildings pg35 1.3 Location, Site Details and 3.3 Site Analysis pg21 Land Ownership pg07 3.4 Existing Access pg24 5.4 Density and Building Heights pg37 1.4 Structure of Brief pg08 3.5 Summary Opportunities 5.5 Detailed Design Appearance pg37 and Challenges pg25 5.6 Sustainable Construction and Energy Efficiency pg39 5.7 Access and Movement pg39 5.8 Parking pg41 5.9 Public Realm and Landscaping pg42 SECTION 2 POLICY CONTEXT SECTION 4 DEVELOPMENT PROPOSALS 5.10 Public Art pg43 2.1 Policy Context pg11 4.1 Development Proposals pg29 5.11 Superfast / Ultrafast Broadband pg43 www.milton-keynes.gov.uk/udla 3 Campbell Park Northside Development Brief: Proposed