Book Proceed. N.10.Indb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPSFC Annual Report 1953

INTERNATIONAL PACIFIC SALMON FISHERIES COMMISSION APPOINTED UNDER A CONVENTION BETWEEN CANADA AND THE UNITED STATES FOR THE PROTECTION, PRESERVATION AND EXTENSION OF THE SOCKEYE SALMON FISHERIES IN THE FRASER RIVER SYSTEM ANNUAL REPORT 1953 COMMISSIONERS ROBERT J. SCHOETTLER SENATOR THOMAS REID A. J. WHITMORE ALBERT M. DAY ELTON B. JONES H. R. MacMILLAN OFFICERS LOYD A. ROYAL ROY I. JACKSON Director Assistant Director NEW WESTMINSTER CANADA 1954 FIGURE 1.-Sockeye spawning scene on the Upper Horsefly River in August 1953, showing the remarkable "Rebirth" of the Quesnel sockeye run. REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL PACIFIC SALMON FISHERIES COMMISSION FOR THE YEAR 1953 In the year 1937 the President of the United States of America and the Government of the Dominion of Canada, recognized that the protection, preservation and extension of the soclieye salmon fisheries in the Fraser River system were of common concern to the United States of America and the Dominion of Canada: that the supply of this fish in recent years had been greatly depleted and that it was of importance to the interests of both countries that this source of wealth be restored and 1tiaintained. A Conv'.ention to the above effect was ratified on July 28, 1937, including therein specific terms of reference for accomplishing the protection, preservation and extension of the sockeye salmon fisheries in the Fraser River system and an equal sharing of the allowable harvest of the resource. The Commission, appointed under the Convention, has now functioned for the initial treaty period of sixteen years with the members appointed originally by Canada and the United States and with individual replacement members appointed later by each country as vacancies occurred. -

Salmon Development Techniques, Their Present Status, and Their Possible Applications to the British Columbia Salmon Stocks

RESTRICTED FOR DEPARTMENTAL USE ONLY DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES OF CANADA RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT BRANCH SALMON DEVELOPMENT TECHNIQUES, THEIR PRESENT STATUS, AND THEIR POSSIBLE APPLICATIONS TO THE BRITISH COLUMBIA SALMON STOCKS VANCOUVER, B. C. OCTOBER. 1966 , RESTRICTED FOR DEPARTMENTAL USE ONLY DEPARTMENT OF FlSHERIES OF CANADA RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT BRANCH SALM 0 N DEVEL 0 PM ENT TE CH NI Q U ES, THEIR PRESENT STATUS, AND THEIR POSSIBLE APPLICATIONS TO THE BRITISH COLUMBIA SALMON STOCKS VANCOUVER, B. C. OCTOBER. 1966, ii CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT vii 1 INTRODUCTION l 2 SALMON DEVELOPMENT TECIIlHQUES 12 1 Hatc;:hery Propagation 12 1 Chinook and Coho Salmon 12 l History 12 2 Recent Advances 13 - Disease Control, Nutrition, Release Practices, Donor Stock 3 Current Program 19 4 Present Status of Hatchery Production 21 - Columbia River Chinook Salmon Hatchery Evaluation Program 21 - Evaluation of the Washington State Chinook and Coho Hatchery Program - Recent Increases in Coho Production by Columbia River Hatcheries 28 2 Sockeye Salmon 29 3 Chum and Pink Salmon 35 4 Summary and Conclusions 43 1 Chinook and Coho Salmon 43 2 Sockeye Salmon 45 3 Pink and Chum Salmon 46 5 References 47 2 Spawning Channels and Controlled Flow Projects 48 1 Introduction 48 2 Assessment of Existing Spawning Channels 50 ) Summary and Conclusions 63 4 Supplemental Information on Existing Spawning Channels and Allied Projects Completed to Date 64 - Nile Creek, Jones Creek, Horsefly Lake, Robertson Creek, Great Central Lake, Seton Creek, Pitt River, Big Qualicum River, Nanika -

Eocene Paleo-Physiography and Drainage Directions, Southern Interior Plateau, British Columbia1

215 Eocene paleo-physiography and drainage directions, southern Interior Plateau, British Columbia1 Selina Tribe Abstract: A map of reconstructed Eocene physiography and drainage directions is presented for the southern Interior Plateau region, British Columbia south of 53°N. Eocene landforms are inferred from the distribution and depositional paleoenvironment of Eocene rocks and from crosscutting relationships between regional-scale geomorphology and bedrock geology of known age. Eocene drainage directions are inferred from physiography, relief, and base level elevations of the sub-Eocene unconformity and the documented distribution, provenance, and paleocurrents of early Cenozoic fluvial sediments. The Eocene landscape of the southern Interior Plateau resembled its modern counterpart, with highlands, plains, and deeply incised drainages, except regional drainage was to the north. An anabranching valley system trending west and northwest from Quesnel and Shuswap Highlands, across the Cariboo Plateau to the Fraser River valley, contained north-flowing streams from Eocene to early Quaternary time. Other valleys dating back at least to Middle Eocene time include the North Thompson valley south of Clearwater, Thompson valley from Kamloops to Spences Bridge, the valley containing Nicola Lake, Bridge River valley, and Okanagan Lake valley. During the early Cenozoic, highlands existed where the Coast Mountains are today. Southward drainage along the modern Fraser, Chilcotin, and Thompson River valleys was established after the Late Miocene. Résumé : Cet article présente une carte reconstituée de la géographie physique et des directions de drainage, à l’Éocène, pour la région du plateau intérieur de la Colombie-Britannique, au sud du 53e parallèle Nord. Les formes de terrain à l’Éocène sont déduites de la distribution et du paléoenvironnement de déposition des roches de l’Éocène et à partir de relations de recoupement entre la géomorphologie à l’échelle régionale et la géologie du socle, d’âge connu. -

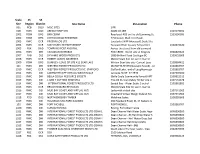

Scale Site SS Region SS District Site Name SS Location Phone

Scale SS SS Site Region District Site Name SS Location Phone 001 RCB DQU MISC SITES SIFR 01B RWC DQC ABFAM TEMP SITE SAME AS 1BB 2505574201 1001 ROM DPG BKB CEDAR Road past 4G3 on the old Lamming Ce 2505690096 1002 ROM DPG JOHN DUNCAN RESIDENCE 7750 Lower Mud river Road. 1003 RWC DCR PROBYN LOG LTD. Located at WFP Menzies#1 Scale Site 1004 RWC DCR MATCHLEE LTD PARTNERSHIP Tsowwin River estuary Tahsis Inlet 2502872120 1005 RSK DND TOMPKINS POST AND RAIL Across the street from old corwood 1006 RWC DNI CANADIAN OVERSEAS FOG CREEK - North side of King Isla 6046820425 1007 RKB DSE DYNAMIC WOOD PRODUCTS 1839 Brilliant Road Castlegar BC 2503653669 1008 RWC DCR ROBERT (ANDY) ANDERSEN Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1009 ROM DPG DUNKLEY- LEASE OF SITE 411 BEAR LAKE Winton Bear lake site- Current Leas 2509984421 101 RWC DNI WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. MAHATTA RIVER (Quatsino Sound) - Lo 2502863767 1010 RWC DCR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. STAFFORD Stafford Lake , end of Loughborough 2502863767 1011 RWC DSI LADYSMITH WFP VIRTUAL WEIGH SCALE Latitude 48 59' 57.79"N 2507204200 1012 RWC DNI BELLA COOLA RESOURCE SOCIETY (Bella Coola Community Forest) VIRT 2509822515 1013 RWC DSI L AND Y CUTTING EDGE MILL The old Duncan Valley Timber site o 2507151678 1014 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD Sandal Bay - Water Scale. 2 out of 2502861881 1015 RWC DCR BRUCE EDWARD REYNOLDS Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1016 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Ladysmith virtual site 2507541962 1017 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Coastland Virtual Weigh Scale at Mu 2507541962 1018 RTO DOS NORTH ENDERBY TIMBER Malakwa Scales 2508389668 1019 RWC DSI HAULBACK MILLYARD GALIANO 200 Haulback Road, DL 14 Galiano Is 102 RWC DNI PORT MCNEILL PORT MCNEILL 2502863767 1020 RWC DSI KURUCZ ROVING Roving, Port Alberni area 1021 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD-DEAN 1 Dean Channel Heli Water Scale. -

Quesnel /Horsefly Lakes Residential Land Assessment

Quesnel /Horsefly Lakes Residential Land Assessment Prepared for: Cariboo Regional District In partnership with Department of Fisheries and Oceans & The Real Estate Foundation of BC August 2009 Head Office: 2144 Kinglet Road Williams Lake BC V2G 5M3 T: (250) 267 2445 F: (250) 305 2445 E: [email protected] Quesnel / Horsefly Lakes Residential Land Assessment 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...............................................................................3 1.1 PUBLIC CONSULTATION SURVEYS ................................................................................................................................3 1.2 PUBLIC INFORMATION...............................................................................................................................................4 1.3 ENVIRONMENTALLY SENSITIVE AREAS (ESAS)................................................................................................................4 1.4 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................................................................5 2. LOCAL GEOGRAPHY...................................................................................6 2.2 TOPOGRAPHY ..........................................................................................................................................................7 2.3 BIOGEOCLIMATIC ECOSYSTEM CLASSIFICATION (BECS)....................................................................................................7 -

2007-06 Pleasure Craft Sewage Regulations

TRANSPORT CANADA OFFICE OF BOATING SAFETY PACIFIC PLEASURE CRAFT COURTESY CHECK BULLETIN Bulletin 06-07 Oct 30,2007 Sewage Discharges (Pleasure Craft) This Transport Canada (TC), Office of Boating Safety Pacific PCCC bulletin is issued under the authority of the Regional Manager Boating Safety, Transport Canada in order to provide clarity and direction to PCCC checkers. The information in this bulletin provides additional and updated information to the TC PCCC manual. Any questions or enquires concerning this bulletin or any other particulars of the TC PCCC program are to be directed to Boating Safety Officer Mike Mitchell, Officer Primary Interest Transport Canada Pleasure Craft Courtesy Check Program. mailto:[email protected] (250-363-0099) Introduction: The Pleasure Craft Sewage Prevention Regulations have been repealed and replaced by subdivision 4, of The Regulations for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships and for Dangerous Chemicals Act. This bulletin is an amendment to the PCCC manual March 2004, 4th Edition. Please, remove or cross out the ‘The Pleasure Craft Sewage Prevention Regulations’ section and insert this bulletin. Reference to the Regulations in this bulletin are not complete, this information has been edited and modified for the purposes of the bulletin, only some of the provisions related to pleasure craft have been included in this bulletin. The complete text of the regulations can be found at the following Internet link: http://www.tc.gc.ca/acts- regulations/GENERAL/C/csa/regulations/400/csa450/csa450.html#p2d4- sewage 1. Interpretations: a. Sewage; Sewage means human body wastes and wastes from other living animals. Drainage and other wastes from toilets and other receptacles intended to receive or retain human body wastes. -

For Fraser River Chinook Salmon Conservation) Pour Le Saumon Quinnat Du Fraser

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2002/085 Document de recherche 2002/085 Not to be cited without Ne pas citer sans permission of the authors * autorisation des auteurs * A discussion paper on possible new Document de travail sur les nouveaux stock groupings (Conservation Units) agrégats possibles de stocks (unités de for Fraser River chinook salmon conservation) pour le saumon quinnat du Fraser J. R. Candy1, J. R. Irvine1, C. K. Parken1, S. L. Lemke2, R. E. Bailey2, M. Wetklo1 and K. Jonsen1 1 Fisheries and Oceans Canada Science Branch, Pacific Biological Station Nanaimo, B.C. V9T 6N7 2Fisheries and Oceans Canada B.C. Interior, Resource Management 1278 Dalhousie Drive, Kamloops, B.C. V2B 6G3 * This series documents the scientific basis for the * La présente série documente les bases scientifiques evaluation of fisheries resources in Canada. As such, des évaluations des ressources halieutiques du Canada. it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames Elle traite des problèmes courants selon les échéanciers required and the documents it contains are not dictés. Les documents qu’elle contient ne doivent pas intended as definitive statements on the subjects être considérés comme des énoncés définitifs sur les addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing sujets traités, mais plutôt comme des rapports d’étape investigations. sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans la language in which they are provided to the langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit envoyé au Secretariat. -

Rangifer Tarandus Caribou) in BRITISH COLUMBIA

THE EARLY HISTORY OF WOODLAND CARIBOU (Rangifer tarandus caribou) IN BRITISH COLUMBIA by David J. Spalding Wildlife Bulletin No. B-100 March 2000 THE EARLY HISTORY OF WOODLAND CARIBOU (Rangifer tarandus caribou) IN BRITISH COLUMBIA by David J. Spalding Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Wildlife Branch Victoria BC Wildlife Bulletin No. B-100 March 2000 “Wildlife Bulletins frequently contain preliminary data, so conclusions based on these may be sub- ject to change. Bulletins receive some review and may be cited in publications. Copies may be obtained, depending upon supply, from the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, Wildlife Branch, P.O. Box 9374 Stn Prov Gov, Victoria, BC V8W 9M4.” © Province of British Columbia 2000 Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Spalding, D. J. The early history of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in British Columbia (Wildlife bulletin ; no. B-100) Includes bibliographical references : p. 60 ISBN 0-7726-4167-6 1. Woodland caribou - British Columbia. 2. Woodland caribou - Habitat - British Columbia. I. British Columbia. Wildlife Branch. II. Title. III. Series: Wildlife bulletin (British Columbia. Wildlife Branch) ; no. B-100 QL737.U55S62 2000 333.95’9658’09711 C00-960085-X Citation: Spalding, D.J. 2000. The Early History of Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) in British Columbia. B.C. Minist. Environ., Lands and Parks, Wildl. Branch, Victoria, BC. Wildl. Bull. No. 100. 61pp. ii DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks. In cases where a Wildlife Bulletin is also a species’ status report, it may contain a recommended status for the species by the author. -

Geology and Mineral Deposits

Energiand Mink& Division Geological Survey Branch GEOLOGY AND MINERAL DEPOSITS OF THE QUESNEL RIVER- HORSEFLY MAP AREA, CENTRAL QUESNEL TROUGH, BRITISH COLUMBIA NTS MAP SHEETS 93A/5,6,7, 11,12,13; 93B/9,16; 93G/1; 93W4 By A. Panteleyev, P.Eng., D.G. Bailey, P.Geo. M.A. Bloodgood, P.Geo. and K.D. Hancock, P.Geo. BULLETIN 97 Canadian Cataloguingin Publication Data Main entry under title: Geology and mineral deposits of Ule Quesnel Riva~ Horsefly mal area, central Qnesnel Trough, British Columbia NIS map sheets 93A15,6.7.11,12,13: 93BR. 16: 93W1; 93W4 (Bulletin ; 97) Issued bv Gecloeical- Survev Branch. Includes bibliographical references: p. VICTORIA ISBN 0-7726-2973-0 BRITISH COLUMBIA CANADA 1. Geology - British Columbia - Quesrvel Riva Region August 1996 2. Geochemistry - British Columbia - Qnesnel River Region. 3. Geology, Economic - British Columbia - Qwsnel River Region. 4. Mines and mined resources - British Columbia - Quesnel River Region. I. Panteleyev, Andrejs, 1942 U. British Columbia. Ministryof Employment and Investment m.Bhh Cohnnbia. Ceorogical Survey Branch. N.Title. V. Series: Bulletin (British Columbia. Ministryof Employmentandlnvesunent) ; 97. QE187.G46 1996 557.11'75 w-9-9 Frontispiece. Quesnel River, viewlooking east (upstream)from the QR deposit towards Quesnel Forks British Columbia iv Geological Survey Branch Ministry of Employment and lnvesnnent The Quesnel and Horsefly rivers traverse the north- the easternmostpart of the map area. Metamorph,c gradein westerly trending axis of the central Qnesnel belt, also the volcanic rocksis subgreenschist, consistent with burial known as the 'Quesnel Trough'. Since 1859 the region has metamorphism. Commonlythere is extensive chl'xitization been thesite of significantplacer gold prcductiou including of mafic minerals; zeolite and calcite fill arnyf;dules and some very large-scale mining operations.The identification occur in fractures in rocks throughout the regi.on. -

History of the Provincial Forest Inventory Program

A HISTORY OF THE BRITISH COLUMBIA PROVINCIAL FOREST INVENTORY PROGRAM* PART TWO THE POGUE ERA: 1940 - 1960 Written by ROBERT E. BREADON “Too bad it isn’t morning, so we could fly at ‘er again!” Mickey Pogue et al. MAY 2017 THE ORIGINAL WORK WAS COMPLETED IN 1995 © Forest History Association of British Columbia, Victoria, B.C. *This version contains some changes made to the final edit by Jacy Eberlein, who digitized and created this file in July 2014 using a printed copy lent by Bob Breadon. Formatting, design and additional editing were carried out by John Parminter in 2016 and 2017. ii INTRODUCTION In 1991, while gathering material for articles on the early history of the Research Branch of the B.C. Forest Service, I began to realize that many old-timers of the 1920s and 1930s were still active and alert. I also discovered that several had worked in both the research and forest surveys divisions. A little more digging indicated that there were still around 30 survivors who had worked in forest surveys during the pre-war period. I felt that it would be worthwhile for someone to interview these old-timers, and preserve a record of their experiences in the B.C. Forest Service while the opportunity still existed. I discussed the matter with Dave Gilbert, Director of the current Resource Inventory Branch, and he concurred. He also felt that any history project of this nature should cover events right up to the present time. I then commenced to seek a volunteer to write the next section of the project. -

Canadian Rocky Mountains Ecoregional Assessment

CANADIAN ROCKY MOUNTAINS ECOREGIONAL ASSESSMENT Volume Two: Appendices British Columbia Conservation Data Centre CANADIAN ROCKY MOUNTAINS ECOREGIONAL ASSESSMENT • VOLUME 2 • APPENDICES i Citation: Rumsey, C., M. Wood, B. Butterfield, P. Comer, D. Hillary, M. Bryer, C. Carroll, G. Kittel, K.J. Torgerson, C. Jean, R. Mullen, P. Iachetti, and J. Lewis. 2003. Canadian Rocky Mountains Ecoregional Assessment, Volume Two: Appendices. Prepared for The Nature Conservancy and the Nature Conservancy of Canada. Cover page photo credits: Top, left to right: The Nature Conservancy of Canada’s Mount Broadwood Conservation Area (Dave Hillary); Water howellia (howellia aquatilis); Grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) (Dave Fraser); Northern Leopard Frog (rana pipiens), Columbia Valley Wildlife Management Area (Dave Hillary); Maligne Lake, Jasper National Park (Pierre Iachetti) Bottom, left to right: Mission Valley, Montana (Marilyn Wood); Palouse Prairie, Idaho (KJ Torgerson); Harlequin duck (histrionicus histrionicus) CANADIAN ROCKY MOUNTAINS ECOREGIONAL ASSESSMENT • VOLUME 2 • APPENDICES ii TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX 1.0 SPECIES CONSERVATION TARGETS...................................................... 1 APPENDIX 1.1 CONSERVATION TARGETS CHARACTERISTICS............................... 23 APPENDIX 1.2 HABITATS/ECOSYSTEMS CONSERVATION TARGETS .................... 24 APPENDIX 1.3 GOALS CAPTURED IN THE CANADIAN ROCKY MOUNTAINS ECOREGIONAL PORTFOLIO ................................................................... 27 APPENDIX 2.0 ECOLOGICAL LAND UNITS -

Quesnel /Horsefly Lakes Residential Land Assessment

Quesnel /Horsefly Lakes Residential Land Assessment Prepared for: Cariboo Regional District In partnership with Department of Fisheries and Oceans & The Real Estate Foundation of BC August 2009 Head Office: 2144 Kinglet Road Williams Lake BC V2G 5M3 T: (250) 267 2445 F: (250) 305 2445 E: [email protected] Quesnel / Horsefly Lakes Residential Land Assessment 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...............................................................................3 1.1 PUBLIC CONSULTATION SURVEYS ................................................................................................................................3 1.2 PUBLIC INFORMATION...............................................................................................................................................4 1.3 ENVIRONMENTALLY SENSITIVE AREAS (ESAS)................................................................................................................4 1.4 RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................................................................................................................5 2. LOCAL GEOGRAPHY...................................................................................6 2.2 TOPOGRAPHY ..........................................................................................................................................................7 2.3 BIOGEOCLIMATIC ECOSYSTEM CLASSIFICATION (BECS)....................................................................................................7