Mcnair SCHOLARS PROGRAM RESEARCH JOURNAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISPENSATION and ECONOMY in the Law Governing the Church Of

DISPENSATION AND ECONOMY in the law governing the Church of England William Adam Dissertation submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Wales Cardiff Law School 2009 UMI Number: U585252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585252 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..................................................................................................................................VI ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................................................................................VII TABLE OF STATUTES AND MEASURES............................................................................................ VIII U K A c t s o f P a r l i a m e n -

St. Mary-The-Virgin a Ll F O R J Es Us , to Th E G L O Ry of G Od Th E F a Th Er , in Th E P Ow E R of the H O Ly Sp I R It

3 ST. LEONARDS AVENUE. HA3 8EJ www.stmaryskenton.org 5TH JANUARY 2020 St. Mary-the-Virgin A ll f o r J es us , to th e G l o ry of G od th e F a th er , in th e p ow e r of the H o ly Sp i r it. Welcome to St Mary’s Clergy: on the Feast of The Father Matthew Cashmore SSC Epiphany of The Lord [email protected] 020 3882 0553 [24/7] A3 Versions of this sheet are available Father Edward Lewis Chaplain to Her Majesty The Queen Please come to help plan our Surrogate Rosary of Our Lady year at St Mary’s – Monday th [email protected] Rosary is said at 6 January at 7.00pm. 07500 557953 [24/7] 6.00pm on Tuesday evenings and Thanks to everyone who Self Supporting Minister everyone is welcome. prepared the Church for Father Mike Still Christmas. It looks stunning [email protected] and is the result of dedicated people working hard. Priest In Residence The Rev’d. Canon Fr. John Metivier SSC The Fulham Epiphany Festival is on the 11th January at Churchwardens: Southwark Cathedral See the Kenrick Elliott - 020 8204 3606 poster in church. All welcome. Winslow Maloney - 020 8933 7088 St-Marys-WiFi Access the internet We need new people for the Please let Fr. Edward or Fr. Matthew using our new WiFi. intercession rota. All training is know of illness or other need as soon as Password is possible, both are available 24/7 on the holymary provided and it’s a wonderful way to offer yourself in service numbers above. -

Coidfoesec Gnatsaeailg

DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA YEARBOOK & CALENDAR 2017 £3.00 EastAnglia2017YearbookFrontSection_Layout 1 22/11/2016 11:29 Page 1 1 DIOCESE OF EAST ANGLIA (Province of Westminster) Charity No. 278742 Website: www.rcdea.org.uk Twinned with The Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem and The Apostolic Prefecture of Battambang, Cambodia PATRONS OF THE DIOCESE Our Lady of Walsingham, 24th September St Edmund, 20th November St Felix, 8th March St Etheldreda, 23rd June BISHOP Rt Rev Alan Stephen Hopes BD AKC Bishop’s Residence: The White House, 21 Upgate, Poringland, Norwich, Norfolk NR14 7SH. Tel: (01508) 492202 Fax:(01508) 495358 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rcdea.org.uk Cover Illustration: Bishop Alan Hopes has an audience with Pope Francis during a Diocesan pilgrimage to Rome in June 2016 EastAnglia2017YearbookFrontSection_Layout 1 22/11/2016 11:29 Page 2 2 Contents CONTENTS Bishop’s Foreword........................................................................................ 5 Diocese of East Anglia Contacts................................................................. 7 Key Diary Dates 2017.................................................................................. 14 Pope Francis................................................................................................ 15 Catholic Church in England and Wales..................................................... 15 Diocese of East Anglia................................................................................ 19 Departments...................................................................... -

Faithfulcross

FAITHFUL CROSS A HISTORY OF HOLY CROSS CHURCH, CROMER STREET by Michael Farrer edited by William Young ii FAITHFUL CROSS A HISTORY OF HOLY CROSS CHURCH, CROMER STREET by Michael Farrer edited by William Young, with additional contributions by the Rev. Kenneth Leech, and others Published by Cromer Street Publications, Holy Cross Church, Cromer Street, London WC1 1999 © the authors Designed by Suzanne Gorman Print version printed by ADP, London. The publishers wish to acknowledge generous donations from the Catholic League and members of the Regency Dining Club, and other donors listed in the introduction, which have made this book possible. iii Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................... vi Introduction .................................................................................................. 1 The Anglo-Catholic Mission ........................................................................ 5 Late Victorian Cromer Street ..................................................................... 17 Holy Cross and its Architect ...................................................................... 23 The Consecration ........................................................................................ 28 The Rev. and Hon. Algernon Stanley ........................................................ 33 The Rev. Albert Moore .............................................................................. 37 The Rev. John Roffey ................................................................................ -

A Glorious and Salutiferous Œconomy...?

A Glorious and Salutiferous Œconomy...? An ecclesiological enquiry into metropolitical authority and provincial polity in the Anglican Communion Alexander John Ross Emmanuel College A dissertation submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Divinity Faculty University of Cambridge April 2018 This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It is not substantially the same as any that I have submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for a degree or diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. I further state that no substantial part of my dissertation has already been submitted, or, is being concurrently submitted for any such degree, diploma or other qualification at the University of Cambridge or any other University or similar institution except as declared in the Preface and specified in the text. It does not exceed the prescribed word limit for the Faculty of Divinity Degree Committee. 2 Alexander John Ross A Glorious and Salutiferous Œconomy…? An ecclesiological enquiry into metropolitical authority and provincial polity in the Anglican Communion. Abstract For at least the past two decades, international Anglicanism has been gripped by a crisis of identity: what is to be the dynamic between autonomy and interdependence? Where is authority to be located? How might the local relate to the international? How are the variously diverse national churches to be held together ‘in communion’? These questions have prompted an explosion of interest in Anglican ecclesiology within both the church and academy, with particular emphasis exploring the nature of episcopacy, synodical government, liturgy and belief, and common principles of canon law. -

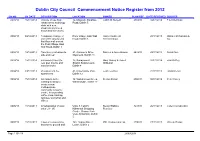

Commencement Notice Register from 2012

Dublin City CouncilCommencement Notice Register from 2012 CN NO CN DATE DESCRIPTION LOCATION OWNER PLAN REF DATE RECEIVED BUILDER 0001/14 16/01/2014 Change of use from 16, Maypark, Malahide Judith M. Nugent 2969/13 02/01/2014 T & I Merriman restaurant to audiology Road, Dublin 5 clinic with new shopfront signage & associated site works 0002/13 04/12/2013 Temporary change of Point Village, East Wall Harry Crosbie (In 25/11/2013 Michael McNamara & use of the ground and Road, Dublin 1. Receivership) Co. first floor mall area at the Point Village, East Wall Road, Dublin 1 0003/13 10/12/2013 Two-storey extension to 21, Glasnevin Drive, Damien & Anne Owens 2432/13 25/11/2013 Denis Finn side and rear Glasnevin, Dublin 11 0003/14 15/01/2014 Extension (35m2) to 15, Sandymount Mary Dowey & Robert 02/01/2014 Paul Dufficy rear plus interior and Strand, Sandymount, McMullan exterior works Dublin 4 0004/13 29/11/2013 Provision of 4 no. 41, Ravensdale Park, Jean Leonard 22/11/2013 David Mellon apartments Dublin 12 0004/14 15/01/2014 Alterations to the 12, Walkinstown Green, Declan Ronan 2960/13 02/01/2014 Peter Casey existing building to Walkinstown, Dublin 12 create a new multi-purpose community resource centre, incorporating coffee shop, training facilities, workshop and offices. 0005/13 11/12/2013 Amalgamation of retail Units 3 4 and 5 Kieran Wallace 3233/13 26/11/2013 Collen Construction units U3 - U5 Kilbarrack Shopping Receiver Centre, Grange Park View, Kilbarrack, Dublin 5 0007/13 11/12/2013 Fitout of restaurant to 141, Baggot Street PNL Restaurants Ltd. -

General Mctovb of 2&Riti£F> An& Foreign Literature ALL NEW WOKKS

OL. IRegiiteredf orTrmumluUm Abroad. f^6 1044—V XLIV. | -jspjto' n THE "|Vf °XA B AND General Mctovb of 2&riti£f> an& forei gn literature CONTAINING A COMPLETE ALPHABETICAL LIST OP ALL NEW WOKKS PUBLISHED IN GREAT BRITAIN AND EVERY WORK OF INTER EST PUBLISHED ABROAD [Issued on tbe 1st and 15th. of eech Month ] i Pake sa. March 15, 1 881 §S: ?S ra con"te isrrcs LITEBAB.Y INTELLIGENCE 201—213 PUBLISEEBS' NOTICES OF BOOKS JTTST ISSUED 207 OBITUARY .¦ , 208 BOOKS RECEIVED , 208—213 INDEX TO BOOKS PUBLISHED IN 0-REAT BRITAIN BETWEEN MARCH 1 AND 15 213, 214 BOOKS PTTBUSHBD IN GREAT BRITAIN FROM MARCH 1 TO 15 214—218 AMEBICAN NEW BOOKS 218, 219 BOOKS NOW ITR8T ADVERTISED AS PUBLISHED 219—223, 240 «¦« aa ¦ vv —' w ^~^ ^" ^ BOOKS ^™ *** *• ¦ ^ B ^^^^ p ^ p ^ # # A ft 0 0 0ft # ft 1 4 A i £ A A A ft 1 A ¦ a a A A a A a a £ A a a A A a A A tt t 0 A A ¦ 0 t 0 0 ft • 0 • % • ^ # • # ft w 0 • • • ft VV • • • • * ^^ ** ^ *^ ^ IN THE PKESS a* 219—231, 240 » * «»_ _ _ _ _ i. NW EDITIONS AND BOOKS LATELY PUBLISHED 230, 231 MISCELLANEOUS 282—239 BUSINESSESvuku-u j iooj uo FORVAJXt, SALEoAXfXS *o*284 " " • ' ASSISTANTS WANTED . 234, 235 WANT SITUATIONS " ' 235 1%^%^%^^V^lH b^^A - _ . '. .^ _ -a- ^ A. BOOKS WANTED TO PURCHASE , 236—239 I 3ST3DEJ3C TO ADVERTISERS ood jktaF&Son ,.; 222 234 (G.) 234 (James) 232 Hodgson.CA.)& Sons 234 NewmanOlyett S^^ & Co Holden 223 lyrHjtt-), Waldron 223 Leipsig Bibliographic Institution . -

Banking Act Unclaimed Money As at 31 December 2007

Commonwealth of Australia Gazette No. ASIC 40A/08, Wednesday, 21 May 2008 Published by ASIC ASIC Gazette Contents Banking Act Unclaimed Money as at 31 December 2007 RIGHTS OF REVIEW Persons affected by certain decisions made by ASIC under the Corporations Act 2001 and the other legislation administered by ASIC may have rights of review. ASIC has published Regulatory Guide 57 Notification of rights of review (RG57) and Information Sheet ASIC decisions – your rights (INFO 9) to assist you to determine whether you have a right of review. You can obtain a copy of these documents from the ASIC Digest, the ASIC website at www.asic.gov.au or from the Administrative Law Co-ordinator in the ASIC office with which you have been dealing. ISSN 1445-6060 (Online version) Available from www.asic.gov.au ISSN 1445-6079 (CD-ROM version) Email [email protected] © Commonwealth of Australia, 2008 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all rights are reserved. Requests for authorisation to reproduce, publish or communicate this work should be made to: Gazette Publisher, Australian Securities and Investment Commission, GPO Box 9827, Melbourne Vic 3001 ASIC GAZETTE Commonwealth of Australia Gazette ASIC 40A/08, Wednesday, 21 May 2008 Banking Act Unclaimed Money Page 2 of 463 Specific disclaimer for Special Gazette relating to Banking Unclaimed Monies The information in this Gazette is provided by Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions to ASIC pursuant to the Banking Act (Commonwealth) 1959. The information is published by ASIC as supplied by the relevant Authorised Deposit-taking Institution and ASIC does not add to the information. -

Pew Sheet 6Th January 2019

For Our Prayers Week beginning 6th January 2019 We pray for the Holy Catholic Church and our Parish: Divine Office Week 2 th Pope Francis ; The Archbishop of Canterbury Justin; The Monday 7 Christmas Feria Bishop of Londonarted The Rt Revd & Rt Hon Dame Sarah 8:15 Morning Prayer & Mass Mullally. Our Bishop Jonathan; Our Churchwardens, Ken, 5:45 Evening Prayer Winslow and PCC Members. For all persecuted Christians. Intention: Those training for ministry: Mike Still Pray for Pastors Irani,Saeed, Li Hepping Pastors in Iran, Years Mind: Edwin John Taylor, Clara Lavinia Soar, Ivy Verney, and those in communist ‘re-education’ camps Hyla Rose Holden (priest) ************************************************** We pray daily for the elderly, infirm, those in need; for those being Tuesday 8th Christmas Feria nursed in hospitals or at home; those who have asked for prayers: 8:15 Morning Prayer Christine Smith; Del Carter; Florence & Massias Sylvester; 10:15 Parish Prayer Group John Capper; James Scott; Margarita; Brian Foy; Lina & Clive 6:00 Holy Rosary Thomas; Georgina; Debbie DeSouza; Noel Small; Mark; Ivan 6:30 Evening Prayer & Adoration Cowans; Anthony Thomas; Valerie Southwood; Edward Huntley; Valerie D’Souza; Corine Farmer; Margaret Shand; 7:00 Mass Mark Taylor; Karl Liechti; Peggy Aris; Debra; Bunny Martin; Intention: Those at the margins of society Years Mind: Edward James Misseldine, Thomas Smith, William Soar, Penny; Maureen; Lisa Rice: Andrew McAlister; Julie; Alison, Philip Bevan, pr., Amy Prudence Wallis , Frederick Rosche Khial, Blaise, -

Universally Condemned’ by Amaris Cole One Lay Blogger, Anne Brooke, Called the This Was the Case

E I D S IN Spend the evening with Joan Collins E6 THE SUNDAY, APRIL 21, 2013 No: 6173 www.churchnewspaper.com PRICE £1.35 1,70j US$2.20 CHURCH OF ENGLAND THE ORIGINAL CHURCH NEWSPAPER ESTABLISHED IN 1828 NEWSPAPER Marriage report ‘universally condemned’ By Amaris Cole One lay blogger, Anne Brooke, called the this was the case. “I greatly welcome this clear and positive latest outcry a ‘real humdinger’. The Rt Rev Christopher Cocksworth statement about the unique place that mar- THE CHURCH of England’s new report on She wrote: “So, this new Church of Eng- said: “I would like them to know that they riage holds within society as a whole. It marriage has been ‘universally con- land Report tells us that the only sexual are obviously welcome in the life of the makes clear that there is no such thing as demned’, commentators are claiming. norm is for men and women to be married Church and will find many people in the “civil” or “religious” marriage as though The ‘Men and Women in Marriage’ docu- to the opposite gender which is apparently same position as them and that their parish the two were different: they are not and ment could see gay couples receiving What God Wants, and everything else is a priest will want to offer them the love, care never have been.” prayers similar to those said in a marriage sinful second-rate lifestyle, otherwise and attention of the Church.” But Christians for Equal Marriage UK, service thanks to the document released known as The Work Of The Devil. -

The Ordinariate Liturgy THERE IS a Story About Mgr Graham Leonard, Formerly Anglican Bishop of London, Being Asked by Cardinal H

The Ordinariate Liturgy THERE IS a story about Mgr Graham Leonard, formerly Anglican Bishop of London, being asked by Cardinal Hume what he valued in the worship of the Church of England and would miss as a Catholic. He replied that it would be the Prayer Book Offices of Matins and Evensong, and in particular the psalms in course, following the Coverdale Psalter, as set in the Book of Common Prayer. There is no doubt that the daily services are the jewel in the crown and, when both Pope Paul VI and Pope Benedict XVI expressed their admiration for Anglican worship, it was the public celebration of the Offices that they had most clearly in mind. Small wonder then that the Ordinariate clergy in the United Kingdom particularly value the availability to them, as Catholics, of Morning and Evening Prayer in the Prayer Book tradition, as distilled in the Customary of Our Lady of Walsingham. But what of the Mass? Looking back at the classical Anglican rite of Holy Communion, this is clearly a Protestant service. Yet there is much that can be rescued. The Ordinariate’s Order of Mass incorporates this material and presents it in a shape largely familiar to congregations of the period up to about 1965 in such unlawful but widely used adaptations of the Roman Mass as the English Missal and Anglican Missal. Fifty years have now elapsed and Anglo-catholic congregations in England and Wales have almost entirely used the modern Anglican and Roman rites during this period. Nevertheless, it is good that there is a distinct Ordinariate Order of Mass, that it is in the sacral language of the Prayer Book, and that, though it will not be usable in many pastoral contexts, there will be some in which it is entirely right. -

To View a Century Downtown: Sydney University Law School's First

CENTURY DOWN TOWN Sydney University Law School’s First Hundred Years Edited by John and Judy Mackinolty Sydney University Law School ® 1991 by the Sydney University Law School This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism, review, or as otherwise permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Typeset, printed & bound by Southwood Press Pty Limited 80-92 Chapel Street, Marrickville, NSW For the publisher Sydney University Law School Phillip Street, Sydney ISBN 0 909777 22 5 Preface 1990 marks the Centenary of the Law School. Technically the Centenary of the Faculty of Law occurred in 1957, 100 years after the Faculty was formally established by the new University. In that sense, Sydney joins Melbourne as the two oldest law faculties in Australia. But, even less than the law itself, a law school is not just words on paper; it is people relating to each other, students and their teachers. Effectively the Faculty began its teaching existence in 1890. In that year the first full time Professor, Pitt Cobbett was appointed. Thus, and appropriately, the Law School celebrated its centenary in 1990, 33 years after the Faculty might have done. In addition to a formal structure, a law school needs a substantial one, stone, bricks and mortar in better architectural days, but if pressed to it, pre-stressed concrete. In its first century, as these chapters recount, the School was rather peripatetic — as if on circuit around Phillip Street.