King's Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Saffron Burrows, Oliver Chris and Belinda Stewart-Wilson join cast of Everything I Ever Wanted to Tell My Daughter About Men 29 January 2020 Shakespeare’s Globe is delighted to announce further casting for Everything I Ever Wanted to Tell My Daughter About Men, a new black comedy by actor and writer Lorien Haynes, directed by Tara Fitzgerald (Brassed Off, Game of Thrones), being hosted in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse on Thursday 20 February. Everything I Ever Wanted to Tell My Daughter About Men traces a woman’s relationship history backwards, exploring the impact of sexual assault, addiction and teen pregnancy on her adult relationships. Presented in association with RISE and The Circle, all profits from this event will go towards supporting survivors of sexual violence. Thanks in huge part to RISE’s work, the event will also mark the planned introduction of the Worldwide Sexual Violence Survivor Rights United Nations Resolution later this year, which addresses the global issue of sexual violence and pens into existence the civil rights of millions of survivors. Nobel-Prize nominee and founder of Rise, Amanda Nguyen, will introduce the evening. A silent auction will also take place on the night to highlight and raise awareness for the support networks available to those in need. Audience members will be able to bid on props from the production as well as a selection of especially commissioned rotary phones, exclusively designed by acclaimed British artists including Harland Miller, Natasha Law, Bella Freud and Emma Sargeant. The money raised by each phone will go to a rape crisis helpline chosen by the artist. -

3D Computer Modelling the Rose Playhouse Phase I (1587- 1591) and Phase II (1591-1606)

3D Computer Modelling The Rose Playhouse Phase I (1587- 1591) and Phase II (1591-1606) *** Research Document Compiled by Dr Roger Clegg Computer Model created by Dr Eric Tatham, Mixed Reality Ltd. 1 BLANK PAGE 2 Contents Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………….………………….………………6-7 Foreword…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….9-10 1. Introduction……………………..………...……………………………………………………….............………....11-15 2. The plot of land 2.1 The plot………………………………………………..………………………….………….……….……..…17-19 2.2 Sewer and boundary ditches……………………………………………….……………….………….19-23 3. The Rose playhouse, Phase I (1587-1591) 3.1 Bridges and main entrance……………………..……………………………………,.……………….25-26 3.2 Exterior decoration 3.2.1 The sign of the Rose…………………………………………………………………………27-28 3.2.2 Timber frame…………………………………………………..………………………………28-31 3.3. Walls…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….32-33 3.3.1 Outer walls………………………………………………………….…………………………..34-36 3.3.2 Windows……………………………………………………………..…………...……………..37-38 3.3.3 Inner walls………………………………………………………………………………………39-40 3.4 Timber superstructure…………………………………………….……….…………….…….………..40-42 3.4.1 The Galleries………………………………………………..…………………….……………42-47 3.4.2 Jutties……………………………………………………………...….…………………………..48-50 3.5 The yard………………………………………………………………………………………….…………….50-51 3.5.1 Relative heights………………………………………………...……………...……………..51-57 3.5.2. Main entrance to the playhouse……………………………………………………….58-61 3.6. ‘Ingressus’, or entrance into the lower gallery…………………………..……….……………62-65 3.7 Stairways……………………………………………………………………………………………………....66-71 -

Shakespeare and London Programme

andShakespeare London A FREE EXHIBITION at London Metropolitan Archives from 28 May to 26 September 2013, including, at advertised times, THE SHAKESPEARE DEED A property deed signed by Mr. William Shakespeare, one of only six known examples of his signature. Also featuring documents from his lifetime along with maps, photographs, prints and models which explore his relationship with the great metropolis of LONDONHighlights will include the great panoramas of London by Hollar and Visscher, a wall of portraits of Mr Shakespeare, Mr. David Garrick’s signature, 16th century maps of the metropolis, 19th century playbills, a 1951 wooden model of The Globe Theatre and ephemera, performance recording and a gown from Shakespeare’s Globe. andShakespeare London In 1613 William Shakespeare purchased a property in Blackfriars, close to the Blackfriars Theatre and just across the river from the Globe Theatre. These were the venues used by The Kings Men (formerly the Lord Chamberlain’s Men) the performance group to which he belonged throughout most of his career. The counterpart deed he signed during the sale is one of the treasures we care for in the City of London’s collections and is on public display for the first time at London Metropolitan Archives. Celebrating the 400th anniversary of the document, this exhibition explores Shakespeare’s relationship with London through images, documents and maps drawn from the archives. From records created during his lifetime to contemporary performances of his plays, these documents follow the development of his work by dramatists and the ways in which the ‘bardologists’ have kept William Shakespeare alive in the fabric of the city through the centuries. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace

No. 495 - June 2016 President: Vice President: Simon Russell Beale CBE Nickolas Grace Nothing like a Dame (make that two!) The VW’s Shakespeare party this year marked Shakespeare’s 452nd birthday as well as the 400th anniversary of his death. The party was a great success and while London, Stratford and many major cultural institutions went, in my view, a bit over-bard (sorry!), the VW’s party was graced by the presence of two Dames - Joan Plowright and Eileen Atkins, two star Shakespeare performers very much associated with the Old Vic. The party was held in the Old Vic rehearsal room where so many greats – from Ninette de Valois to Laurence Olivier – would have rehearsed. Our wonderful Vice-President, Nickolas Grace, introduced our star guests by talking about their associations with the Old Vic; he pointed out that we had two of the best St Joans ever in the room where they would have rehearsed: Eileen Atkins played St Joan for the Prospect Company at the Old Vic in 1977-8; Joan Plowright played the role for the National Theatre at the Old Vic in 1963. Nickolas also read out a letter from Ronald Pickup who had been invited to the party but was away in France. Ronald Pickup said that he often thought about how lucky he was to have six years at the National Theatre, then at Old Vic, at the beginning of his career (1966-72) and it had a huge impact on him. Dame Joan Plowright Dame Joan Plowright then regaled us with some of her memories of the Old Vic, starting with the story of how when she joined the Old Vic school in 1949 part of her ‘training’ was moving chairs in and out of the very room we were in. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Shakespeare’s Globe announces casting for The Taming of the Shrew and Women Beware Women 10 January 2020 Shakespeare’s Globe is delighted to announce full casting for the next two productions opening in the candlelit Sam Wanamaker Playhouse in February: The Taming of the Shrew, directed by Maria Gaitanidi, and Thomas Middleton’s Women Beware Women, directed by Amy Hodge. In an exciting and experimental production, roles for The Taming of the Shrew are to be played by different company members at different performances. The full company comprises: Raymond Anum: Raymond graduated from RADA last year and recently appeared in Youth Without God at The Coronet Theatre. Theatre credits while training include Love and Money, Romeo & Juliet, Philistines and The Last Days of Judas Iscariot (RADA). Ryan Ellsworth: Ryan returns to the Globe, having performed in a Read Not Dead rehearsed reading of The Custom of the Country in 2017. Other recent theatre work includes The Wizard of Oz (Sheffield Crucible), Labyrinth (Hampstead Theatre), Henry V (Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre) and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (Theatr Clwyd). Television includes Angel of Darkness (Netflix) and Island at War (ITV). Film includes A Royal Winter and Bel Ami. Mattia Mariotti: Mattia’s recent theatre work includes La Mai Banale Banalità del Male (Teatro Instabile Genoa), The Temptation of St Anthony (Venue 45, Edinburgh Fringe Festival) and We Long Endure (Barron Theatre, St Andrews). Television includes Invisible Milk. Evelyn Miller: Evelyn returns to the Playhouse having appeared in Deep Night Dark Night earlier this year. She was also part of the Globe on Tour 2019 company, where she performed around the world in Pericles, Comedy of Errors and Twelfth Night. -

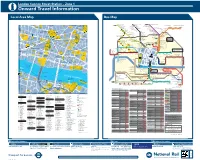

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Cannon Street Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map Palmers Green North Circular Road Friern Barnet Halliwick Park 149 S GRESHAM STREET 17 EDMONTON R 141 1111 Guildhall 32 Edmonton Green 65 Moorgate 12 A Liverpool Street St. Ethelburga’s Centre Wood Green I 43 Colney Hatch Lane Art Gallery R Dutch WALTHAMSTOW F for Reconcilation HACKNEY 10 Church E Upper Edmonton Angel Corner 16 N C A R E Y L A N E St. Lawrence 17 D I and Peace Muswell Hill Broadway Wood Green 33 R Mayor’s 3 T 55 ST. HELEN’S PLACE for Silver Street 4 A T K ING S ’S ARMS YARD Y Tower 42 Shopping City ANGEL COURT 15 T Jewry next WOOD Hackney Downs U Walthamstow E E & City 3 A S 6 A Highgate Bruce Grove RE 29 Guildhall U Amhurst Road Lea Bridge Central T of London O 1 E GUTTER LANE S H Turnpike Lane N St. Margaret G N D A Court Archway T 30 G E Tottenham Town Hall Hackney Central 6 R O L E S H GREEN TOTTENHAM E A M COLEMAN STREET K O S T 95 Lothbury 35 Clapton Leyton 48 R E R E E T O 26 123 S 36 for Whittington Hospital W E LOTHBURY R 42 T T 3 T T GREAT Seven Sisters Lea Bridge Baker’s Arms S T R E E St. Helen S S P ST. HELEN’S Mare Street Well Street O N G O T O T Harringay Green Lanes F L R D S M 28 60 5 O E 10 Roundabout I T H S T K 33 G M Bishopsgate 30 R E E T L R O E South Tottenham for London Fields I 17 H R O 17 Upper Holloway 44 T T T M 25 St. -

PRESS-RELEASE-Shakespeares-Globe-Announces-Winter-Season.Pdf

PRESS RELEASE SHAKESPEARE’S GLOBE ANNOUNCES 2021/22 WINTER SEASON IN THE SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE 1 September 2021 Shakespeare’s Globe has announced its Winter Season for 2021/22 in the candlelit Sam Wanamaker Playhouse. The season will feature Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure directed by Blanche McIntyre, Hamlet directed by Sean Holmes, The Merchant of Venice directed by Abigail Graham, and a festive reimagining of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Fir Tree written by Hannah Khalil. Alongside productions in the Playhouse, there will also be two week-long festivals (including the return of Shakespeare and Race) and half-term events for families. The Globe will continue to reach audiences at home and internationally through livestreamed productions of Measure for Measure, Hamlet and The Merchant of Venice. Michelle Terry, Artistic Director, said: “As we slowly emerge from a period of deep uncertainty, change and challenge, we turn to these plays to ask some of the most profound questions about who we are, why we are, and what on earth can we do about it. In a quest for love, identity, justice or revenge, these plays are full of people making conscious and unconscious choices that determine either their salvation or destruction. This is a season deliberately designed to tackle the big moral questions and complexities with heart, humour and humanity.” For the very first time, audiences will be able to buy tickets to the main productions in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse for £5, with 48 standing tickets available per show. The Globe’s Summer Season continues until 30 October, and despite restrictions and continued difficulties with the pandemic, has successfully welcomed over 86,000 audience members into 150 performances, with only 2 cancelled to date. -

25, Playhouses and Other Early Modern Playing Venues Leslie Thomson, University of Toronto

Audiences at the Red Bull: A Review of the Evidence Recently, the view that the Red Bull audience consisted largely of “unlettered” members of the lower classes has been challenged by several scholars, notably Marta Straznicky, Tom Rutter and Eva Griffith. On the other hand, Mark Bayer seems to confirm the traditional view, though he rejects the assumption that this meant the performances were of low artistic value. In this paper I look carefully at the very limited amount of evidence that survives about the patrons of the Red Bull, focusing especially on the period prior to 1625. This evidence consists essentially of a few contemporary references and a group of extant plays believed with varying degrees of certainty to have been performed there. My thesis is that all the above-mentioned scholars are partially right. Early modern theatre companies had to appeal to several different audiences at the same time; while there certainly were apprentices and artisans in the yard, the higher-paying, more numerous, and more socially-prestigious audience in the galleries was likely the main focus of the company’s attention. This audience may have contained a higher proportion of “citizens” than at the Globe, but its main distinguishing feature was a more conservative world view and theatrical taste. Douglas Arrell, University of Winnipeg ******************** Catherine Clifford SAA 2015: Playhouses and Other Early Modern Playing Venues University of Texas at Arlington [email protected] Anne of Denmark’s Temporary Courtyard Theatre and the Consecration of a New Court at Somerset House in 1614 On February 2, 1614, upon the near-completion of extensive renovations at Somerset House, soon to be known as Denmark House, Anne of Denmark hosted a wedding celebration for one of her ladies-in-waiting at her palace. -

Escape the Ordinary...On a Long London Weekend (With Harry Potter Bonus!) Page 2 of 20 Trip Summary

Melanie Tucker 6099230304 Travel Designer [email protected] Rare Finds Travel Design http://www.rarefindstravel.com Escape the Ordinary...on a Long London Weekend (with Harry Potter Bonus!) Page 2 of 20 Trip Summary Day 1 Welcome to London! How to get into the city Lodging choice #1: The Bloomsbury Hotel - The Bloomsbury Hotel Lodging Option #2: 40 Winks (if you want something REALLY special) Lodging choice #3: The Morgan Hotel (where I stay!) Lodging Option #4: One Fine Stay (if you've got a big group) Get oriented with a Free On Foot Tour Trace your American roots at the Ben Franklin House & Mayflower Pub Meet Tom Machett, your London Ambassador for a custom pub crawl tonight A novel dinner idea... Dine in the Dark at Dans Le Noir! Day 2 Morning Scavenger Hunt of British Museum with THATMuse - PDF British Museum map.pdf Afternoon Tea Bus Tour The Big Sites (map below so you can get your bearings) Dinner choice #1: Butler-ed picnic in the park for lunch! Dinner choice #2: Wahacka Dinner choice #3: Bailey's Fish & Chips Want to see a Broadway show in the West End? Day 3 HIGHLY RECOMMENDED Lunchtime East End Food Walk Afternoon Bike tour with Fat Tire London Time to go home BONUS Harry Potter DAY! Warner Bros Studio Tour with double-decker red Harry Potter bus! Harry Potter themed London Walks tour ESCAPE ROOM, Harry Potter style! Sleep in a Harry Potter Suite in the Georgian Hotel Or go all-out and sleep in an Oxford dorm with breakfast in a true Hogwartz-esque dining room! Page 3 of 20 Day 1 Welcome to London! You can arrive by either Heathrow or Gatwick International Airports - or by train from Europe. -

Shakespeare's Globe

SHAKESpeare’S GLOBE & SACKLER STUDIOS EMERSON STREET Globe SUMNER STREET Theatre SOUTHWARK BRIDGE ROAD NEW GLOBE WALK PARK STREET Sam Wanamaker BEAR GARDENS Playhouse BANKSIDE Sackler Studios Anchor ROSE ALLEY Terrace 33 steps Rose Bankside PORTER STREETPlaque marking Theatre site of the original Pier Globe Theatre 34 steps 37 steps Financial Times Building RIVER THAMES 33 PARK STREET steps SOUTHWARK BRIDGE BANKSIDE NORTH SHAKESpeare’S GlOBE PIAZZA LEVEL Lift Lift to Gentlemen’s Box P First Aid (backstage) Room West Piazza GLOBE THEATRE Yard & Lower Gallery Door 4 Door 1 Shop 28 steps up to Middle Gallery 50 steps up to Upper Gallery Friends End point Desk Door 2 Door 3 of tours North East To w e r To w e r Cushions Cushions SAM Stairs up WANAMAKER to Upper Foyer (19 steps) East PLAYHOUSE Piazza Lower Gallery Bankside Gates Entrance (9 steps down Stairs down to to ground level) ground level (15 steps) Stairs up to Restaurant (19 steps) NEW GLOBE WALK Lift Bar BANKSIDE Stairs down to RIVER THAMES ground level (12 steps) NORTH SHAKESpeare’S GlOBE GROUND LEVEL 2 accessible Stage Door parking spaces Reception Ramp Admissions Ramp Desk Lift Tours Entrance Gates to Stairs down parking spaces. to lower level (Press button on (18 steps) wall to call Stage Door for access) Oak Tree UNDERGLOBE Cloakroom SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE Foyer Pit seating Café Bar Bankside Gates Entrance Stairs up to (9 steps up to Stairs down piazza level piazza level) (30 steps) (15 steps) Main Entrance Welcome Desk NEW GLOBE(Accessible WALK button- & Box O� ce operated