Missionaries to Government Service

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lorrin Potter Thurston the Watumull Foundation Oral

LORRIN POTTER THURSTON THE WATUMULL FOUNDAT ION ORAL HI STORY PROJECT Lorrin Potter Thurston (1899 - Lorrin Thurston, widely known retired publish er of the Honolulu Advertiser and one-time chairman of the Hawaii Statehood Commission, is a fourth generation descendant of Asa and Lucy Thurston, first company missionaries to Hawaii in 1820. With his noted father, attorney Lorrin Andrews Thurston, he discovered the Thurston Lava Tubes in the Volcano region on the Island of Hawaii. His community service on Oahu and in Kailua Kana ha:3 been exten : ~i ve. He l'o unded the Pacific Area 'I'ravel Association and, while president of the Outrigger Canoe Club, he started the Waikiki Beach Patrol to keep the club Holvent. Mr. Thurston moved from Honolulu to Kailua Kana in the summer of 1971 with his wife, Barbara Ford Thurston, to build a new home on property he acquired in 1938 and on which Kamehameha the Great lived during the last years of his life. In this transcript, Mr. Thurston relates the interesting history of his property in Kailua-Kana and discusses some of the issues that have caused confrontations between residents of that area. He also describes the discovery of the Thurston Lava Tubes and tells about the founding of the Hawaiian Volcano Research Association by his father in 1911. Katherine B. Allen, Interviewer © 1979 The Watumull Foundation, Oral History Project 2051 Young Street, Honolulu, Hawaii, 96826 All rights reserved. This transcript, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without the permission of the Watumull Foundation. INTERVIEW WITH LORRIN POTTER THURSTON At his Kailua-Kona home, Hawaii, 96740 July 10, 1971 T: Lorrin P. -

An Emersonian in the Sandwich Islands: the Career of Giles Waldo

An Emersonian in the Sandwich Islands: The Career of Giles Waldo Martin K. Doudna In the spring of 1845, two young friends of Ralph Waldo Emerson embarked independently on two very different experiments that were designed to answer some of the problems they faced. One of these experiments, Henry David Thoreau's sojourn of a little over two years at Walden Pond, is well known. The other experiment, Giles Waldo's sojourn of nearly three years in the Hawaiian Islands, deserves to be better known, not only because it provides an interest- ing contrast to Thoreau's experiment but also because it sheds light on the role of consuls and merchants in the Islands in the busy 1840s.1 Giles Waldo (1815 -1849), the eighth of nine children of a farmer in Scotland, Connecticut, came from an established New England family. Like Emerson, he was a descendant of Cornelius Waldo, who had settled in Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1654,2 and his family home—a sturdy two-story New England farmhouse built about 1715—is owned today by the Scotland Historical Society. Emerson met him in January 1843 in Washington, D. C, while there on a lecture tour and described that meeting in a letter to Caroline Sturgis, who was later to marry Waldo's close friend, William Tappan: In the Rotunda of the Capitol, in the organic heart, that is, of our fair continent, my companion brought to me a youth of kindest & gentlest manners and of a fine person, who told me he had wished to see me more than any other person in the country, & only yesterday had expressed that wish. -

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson the Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER of EVERYTHING

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER OF EVERYTHING JACOB ADLER and ROBERT M. KAMINS Open Access edition funded by the National En- dowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Inter- national (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non- commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copy- righted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824883669 (PDF) 9780824883676 (EPUB) This version created: 5 September, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1986 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Thelma C. Adler and Shirley R. Kamins In Phaethon’s Chariot … HAETHON, mortal child of the Sun God, was not believed by his Pcompanions when he boasted of his supernal origin. He en- treated Helios to acknowledge him by allowing him to drive the fiery chariot of the Sun across the sky. Against his better judg- ment, the father was persuaded. The boy proudly mounted the solar car, grasped the reins, and set the mighty horses leaping up into the eastern heavens. For a few ecstatic moments Phaethon was the Lord of the Sky. -

Edward Bliss Emerson the Caribbean Journal And

EDWARD BLISS EMERSON THE CARIBBEAN JOURNAL AND LETTERS, 1831-1834 Edited by José G. Rigau-Pérez Expanded, annotated transcription of manuscripts Am 1280.235 (349) and Am 1280.235 (333) (selected pages) at Houghton Library, Harvard University, and letters to the family, at Houghton Library and the Emerson Family Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society. 17 August 2013 2 © Selection, presentation, notes and commentary, José G. Rigau Pérez, 2013 José G. Rigau-Pérez is a physician, epidemiologist and historian located in San Juan, Puerto Rico. A graduate of the University of Puerto Rico, Harvard Medical School and Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, he has written articles on public health, infectious diseases, and the history of medicine. 3 CONTENTS EDITOR'S NOTE .................................................................................................................................. 5 1. 'Ninety years afterward': The journal's discovery ....................................................................... 5 2. Previous publication of the texts .................................................................................................. 6 3. Textual genealogy: Ninety years after 'Ninety years afterward' ................................................ 7 a. Original manuscripts of the journal ......................................................................................... 7 b. Transcription history ................................................................................................................. -

The Voyage of the Parthian: Life and Religion Aboard a 19Th-Century Ship Bound for Hawai'i

CHARLES WILLIAM MILLER The Voyage of the Parthian: Life and Religion Aboard a 19th-century Ship Bound for Hawai'i What wonder that we so long for release from this little prison-house! —Laura Fish Judd (1828) THE CRIES OF "Land O, Land O" echoed throughout the small ship. Many passengers, both men and women, scrambled on deck, ran to the ship railings, and strained their eyes to behold, for the first time, their new home emerging from the cloudy horizon. Below deck, the excitement became too much for one passenger as her emotions got the best of her. Her screams alarmed some of those who remained in their berths, including one passenger whose recent miscarriage had kept her in bed for over a week. It was not land, however, but only "Cape-fly-away" and, as the passengers watched, their new home dis- solved before their eyes. They returned below deck sorely disap- pointed. The cry went up again that evening, "Land O, Land O," but once again, it was nothing but clouds. The following morning, all eyes searched the western horizon, with each person questioning the other, "Have you seen land yet? Have you seen land yet?" The answer always came back, "No." Land birds were sighted, but not the land. Sailors cursed, passengers prayed, and Charles William Miller teaches in the Department of Philosophy and Religion at the Uni- versity of North Dakota. He is a biblical scholar whose primary research interests focus on the importance of social location in the interpretation of biblical texts. His current project is an examination of the biblical hermeneutics of 19th century missionaries to Hawai'i. -

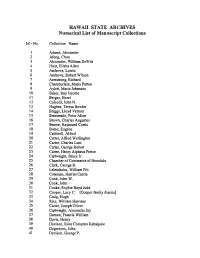

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

Lāhui Naʻauao: Contemporary Implications of Kanaka Maoli Agency and Educational Advocacy During the Kingdom Period a Disserta

LĀHUI NAʻAUAO: CONTEMPORARY IMPLICATIONS OF KANAKA MAOLI AGENCY AND EDUCATIONAL ADVOCACY DURING THE KINGDOM PERIOD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN EDUCATION MAY 2013 By Kalani Makekau-Whittaker Dissertation Committee: Margaret Maaka, Chairperson Julie Kaʻomea Kerry Laiana Wong Sam L. Noʻeau Warner Katrina-Ann Kapā Oliveira ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS E ke kini akua, nā ʻaumākua, a me nā kiaʻi mai ka pō mai, ke aloha nui iā ʻoukou. Mahalo ʻia kā ʻoukou alakaʻi ʻana mai iaʻu ma kēia ala aʻu e hele nei. He ala ia i maʻa i ka hele ʻia e oʻu mau mākua. This academic and spiritual journey has been a humbling experience. I am fortunate to have become so intimately connected with the kūpuna and their work through my research. The inspiration they have provided me has grown exponentially throughout the journey. I am indebted to them for their diligence in intellectualism and in documenting their lives. I hope I have done their story justice. Numerous people have contributed to this dissertation in various ways. I would like to apologize now for any omission of your contribution. Any endeavor such as this requires sacrifices. No one has sacrificed more for my success than my ʻohana—my loving wife, Leinani and our three daughters Kamalu, Leialiʻi and Kamaawākea. To you Leinani, mahalo for all your love and patience throughout this long process. You have kept our ʻohana strong when I needed to work on this project. -

Commemorating the Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial

Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial Commemorating the Hawaiian Mission Bicentennial The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th-century in the United States. During this time, several missionary societies were formed. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was organized under Calvinist ecumenical auspices at Bradford, Massachusetts, on the June 29, 1810. The first of the missions of the ABCFM were to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and India, as well as to the Cherokee and Choctaw of the southeast US. In October 1816, the ABCFM established the Foreign Mission School in Cornwall, CT, for the instruction of native youth to become missionaries, physicians, surgeons, schoolmasters or interpreters. By 1817, a dozen students, six of them Hawaiians, were training at the Foreign Mission School to become missionaries to teach the Christian faith to people around the world. One of those was ʻŌpūkahaʻia, a young Hawaiian who came to the US in 1809, who was being groomed to be a key figure in a mission to Hawai‘i. ʻŌpūkahaʻia yearned “with great earnestness that he would (return to Hawaiʻi) and preach the Gospel to his poor countrymen.” Unfortunately, ʻŌpūkahaʻia died unexpectedly at Cornwall on February 17, 1818. The life and memoirs of ʻŌpūkahaʻia inspired other missionaries to volunteer to carry his message to the Hawaiian Islands. On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of ABCFM missionaries from the northeast US, set sail on the Thaddeus for the Hawaiian Islands. They first sighted the Islands and arrived at Kawaihae on March 30, 1820, and finally anchored at Kailua-Kona, April 4, 1820. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Mission Stations

Mission Stations The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM), based in Boston, was founded in 1810, the first organized missionary society in the US. One hundred years later, the Board was responsible for 102-mission stations and a missionary staff of 600 in India, Ceylon, West Central Africa (Angola), South Africa and Rhodesia, Turkey, China, Japan, Micronesia, Hawaiʻi, the Philippines, North American native American tribes, and the "Papal lands" of Mexico, Spain and Austria. On October 23, 1819, the Pioneer Company of ABCFM missionaries set sail on the Thaddeus to establish the Sandwich Islands Mission (now known as Hawai‘i). Over the course of a little over 40-years (1820- 1863 - the “Missionary Period”), about 180-men and women in twelve Companies served in Hawaiʻi to carry out the mission of the ABCFM in the Hawaiian Islands. One of the earliest efforts of the missionaries, who arrived in 1820, was the identification and selection of important communities (generally near ports and aliʻi residences) as “Stations” for the regional church and school centers across the Hawaiian Islands. As an example, in June 1823, William Ellis joined American Missionaries Asa Thurston, Artemas Bishop and Joseph Goodrich on a tour of the island of Hawaiʻi to investigate suitable sites for mission stations. On O‘ahu, locations at Honolulu (Kawaiahaʻo), Kāne’ohe, Waialua, Waiʻanae and ‘Ewa served as the bases for outreach work on the island. By 1850, eighteen mission stations had been established; six on Hawaiʻi, four on Maui, four on Oʻahu, three on Kauai and one on Molokai. Meeting houses were constructed at the stations, as well as throughout the district. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

"Tools of the Other" Iii. Sp Kalama's

MAPPING THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM: A COLONIAL VENTURE? Kamanamaikalani Beamer and T. Ka'eo Duarte* I. INTRODUCTION II. THE USE OF "TOOLS OF THE OTHER" III. S.P. KALAMA'S 1938 MAP: ACCULTURATION OR TRANSCULTURATION? IV. POLITICS AND LAND IN THE MID-1800s V. PRINCE LOT KAPUAIWA AND THE BOUNDARY COMMISSION VI. (RE)MAPPING THE HAWAIIAN STATE VII. CONCLUSIONS I. INTRODUCTION The early to mid-1800s was an era of tremendous cultural and socio political change for Hawai'i and its native people. A wave of outside influences swept through the islands, inundating the ruling ali'i (chiefs) as well as the maka'ainana (commoners). In addition to many new technologies and materials, this wave introduced ideologies, cultural norms and worldviews foreign to Hawai'i. The establishment of the Kingdom of Hawai'i, with its adoption of and adaptation to "modem" forms of government and policy, represented a fundamental change to Hawaiian society. The ruling ali'i struggled to maintain the sovereignty of their islands in the midst of foreign attempts to gain control over the lands and resources of Hawai'i. Policies implemented during these difficult years may have been a mix of policies that the ali'i were pressured to implement and others ali'i strategically implemented in their attempts to secure their nation's political and cultural future. One of those policies -- the surveying and mapping of Kingdom lands -- not only had political and economic implications, but affected traditional Hawaiian concepts of land di vision and palena (place boundaries). Scholars have suggested that western surveys and maps are tools used to aid "colonizers" in the dispossession of native people from their native lands.