Chapter 1. What Is the Carbon Cycle and Why Do We Care?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Water Cycle

Natural Resource Management Basic concepts and strategies 1 This publication was co-financed by the Catholic Relief Services (CRS) and the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency of International Development (USAID) Office of Acquisition and Assistance under the terms of Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement No. AID-OAA-L-10-00003 with the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign for the Modernizing Extension and Advisory Services (MEAS) Project. MEAS aims at promoting and assisting in the modernization of rural extension and advisory services worldwide through various outputs and services. The services benefit a wide audience of users, including developing country policymakers and technical specialists, development practitioners from NGOs, other donors, and consultants, and USAID staff and projects. Catholic Relief Services (CRS) serves the poor and disadvantaged overseas. CRS provides emergency relief in the wake of natural and man-made disasters and promotes the subsequent recovery of communities through integrated development interventions, without regard to race, creed or nationality. CRS’ programs and resources respond to the U.S. Bishops’ call to live in solidarity – as one human family – across borders, over oceans, and through differences in language, culture and economic condition. CRS provided co-financing for this publication. Catholic Relief Services 228 West Lexington Street Baltimore, MD 21201-3413 USA Illustrations: Jorge Enrique Gutiérrez Printed in the United States of America. ISBN x-xxxxxx-xx-x Download this publication and related material at http://crsprogramquality.org/ or at http://www.meas-extension.org/meas-offers/training © 20[nn] Catholic Relief Services – United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and MEAS project This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. -

Learning the Water, Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles Through the Effects of Intensive Farming Techniques

Learning the Water, Carbon and Nitrogen Cycles through the Effects of Intensive Farming Techniques Winnie Chan Furness High School Overview Rationale Objectives Strategies Classroom Activities Annotated Bibliography/Resources Appendices/Content Standards Overview Elements of natural substances are constantly cycling through Earth. Water, carbon, and nitrogen move through Earth’s many ecosystems in closed paths called the biogeochemical cycles. In this unit, students will learn about these cycles by understanding modern farming techniques used to produce enough food to feed a world population of 7.8 billion. Students will plan and carry out experiments, analyze and interpret data, and communicate the information learned. This curriculum unit is intended for Biology students in Grades 9 and 10. The lessons are meant to be incorporated into “Unit 10: Ecology” of the School District of Philadelphia’s Core Curriculum for Biology, which is typically taught at the end of the year (May/June). Rationale The biogeochemical cycles operate on a fixed amount of matter on Earth. While the total amounts of water, carbon and nitrogen do not change, these substances exist in many different forms. Water is found on Earth as solid ice, liquid water or gaseous vapor. Carbon and nitrogen both exist as in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide gas and nitrogen gas, respectively, or as an integrated part of living and non-living substances. The hydrologic or water cycle describes the constant movement of water through Earth and its atmosphere. Major processes of -

Biogeochemical Cycles

Biogeochemical Cycles Essential Knowledge Objectives 2.A.3 (a) Biogeochemical Cycles • Cycle inorganic and organic nutrients between organisms and the environment – Carbon cycle – Nitrogen cycle – Phosphorus cycle – Water cycle (also known as the hydrological cycle) Cycling of Matter • Organisms must exchange matter with the environment to grow, reproduce and maintain organization • Molecules and atoms from the environment are necessary to build new molecules Molecules Essential for Life • Carbohydrates – composed of C, H, and O, monomer is a monosaccharide • Lipids – composed of C, H, and O, monomers are fatty acids and glycerol • Proteins – composed of C, H, O, N, and S in trace amounts, monomers are amino acids • Nucleic Acids – composed of C, H, O, N and P, monomers are nucleotides Carbon • Carbon moves from the environment to organisms where it is used to build the essential organic molecules • Carbon is used in storage compounds and cell formation in all organisms Carbon in the Environment • Carbon found in something non-living is called inorganic carbon • Inorganic carbon is found in rocks (limestone), shells, the atmosphere and the oceans • Living organisms must “fix” inorganic carbon into organic carbon to build the organic compounds necessary for life Carbon Cycle Nitrogen and Phosphorus • Nitrogen moves from the environment to organisms where it is used to build proteins and nucleic acids • Phosphorus moves from the environment to organisms where it is used to build nucleic acids, certain lipids, and ATP (cell energy) Nitrogen -

Earth Systems and Interactions

The Earth System Earth Systems and Interactions Key Concepts • How do Earth systems What do you think? Read the three statements below and decide interact in the carbon whether you agree or disagree with them. Place an A in the Before column cycle? if you agree with the statement or a D if you disagree. After you’ve read • How do Earth systems this lesson, reread the statements to see if you have changed your mind. interact in the phosphorus Before Statement After cycle? 1. The amount of water on Earth remains constant over time. 2. Hydrogen makes up the hydrosphere. 3. Most carbon on Earth is in the atmosphere. 3TUDY#OACH Earth Systems Make a Table Contrast the carbon cycle and the Your body contains many systems. These systems work phosphorus cycle in a two- together and make one big system—your body. Earth is a column table. Label one system, too. Like you, Earth has smaller systems that work column Carbon Cycle and together, or interact, and make the larger Earth system. Four the other column Phosphorus of these smaller systems are the atmosphere, the Cycle. Complete the table hydrosphere, the geosphere, and the biosphere. as you read this lesson. The Atmosphere Reading Check The outermost Earth system is a mixture of gases and 1. Identify What systems particles of matter called the atmosphere. It forms a layer make up the larger Earth around the other Earth systems. The atmosphere is mainly system? nitrogen and oxygen. Gases in the atmosphere move freely, helping transport matter and energy among Earth systems. -

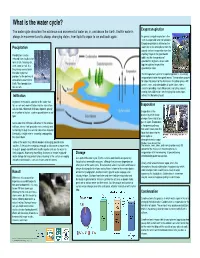

What Is the Water Cycle? Evapotranspiration the Water Cycle Describes the Existence and Movement of Water On, In, and Above the Earth

What is the water cycle? Evapotranspiration The water cycle describes the existence and movement of water on, in, and above the Earth. Earth's water is always in movement and is always changing states, from liquid to vapor to ice and back again. In general, evapotranspiration is the sum of evaporation and transpiration. Evapotranspiration is defined as the Precipitation water lost to the atmosphere from the ground surface, evaporation from the Precipitation is water capillary fringe of the groundwater released from clouds in the table, and the transpiration of form of rain, freezing rain, groundwater by plants whose roots sleet, snow, or hail. It is tap the capillary fringe of the the primary connection in groundwater table. the water cycle that The transpiration aspect of evapotranspiration is essentially provides for the delivery of evaporation of water from plant leaves. Transpiration accounts atmospheric water to the for about 10 percent of the moisture in the atmosphere, with Earth. Most precipitation oceans, seas, and other bodies of water (lakes, rivers, falls as rain. streams) providing nearly 90 percent, and a tiny amount coming from sublimation (ice changing into water vapor Infiltration without first becoming liquid). Anywhere in the world, a portion of the water that falls as rain and snow infiltrates into the subsurface Evaporation soil and rock. How much infiltrates depends greatly on a number of factors, such as ground cover or soil Evaporation is the type. process by which water changes from a liquid to a Some water that infiltrates will remain in the shallow gas or vapor. Evaporation soil layer, where it will gradually move vertically and is the primary pathway horizontally through the soil and subsurface material. -

Chapter 12 the Hydrologic Cycle, the Sediment Cycle, and the Carbon Cycle

CHAPTER 12 THE HYDROLOGIC CYCLE, THE SEDIMENT CYCLE, AND THE CARBON CYCLE 1. INTRODUCTION: SYSTEMS, CYCLES, RESERVOIRS, AND FLUXES 1.1 Thinking about the Earth as a system has become, in recent years, much in vogue. The basic idea of a system is that it is something that consists of a number of distinctive and diverse parts that function together by a variety of interactions and exchanges of energy and matter. Your motor vehicle is a good example of a fairly small and simple system: it is a machine with a number of moving or nonmoving parts, which consumes motor fuel and emits various exhaust substances as it travels from place to place. The Earth is, of course, a far larger and also far more complicated system, whose component parts operate on time scales from seconds to many millions of years. This is the basis for what is nowadays called Earth system science. Here I’m only touching upon some important aspects of Earth systems science that are relevant to this course: the hydrologic cycle and the carbon cycle. A whole course could be devoted to those and certain other cycles that are important in the context of the Earth’s surface environment. 1.2 The concept of cycles plays a fundamental role in systems thinking— although it’s not easy to frame a suitable definition of such cycles. A cycle might best be described as a characteristic succession of events and processes , involving certain kinds of Earth materials, by which the materials reside in certain kinds of places and move among such places in certain ways. -

The Cycles of Nature

Science Enhanced Scope and Sequence – Life Science The Cycles of Nature Strand Life Systems Topic Investigating the carbon cycle, water cycle, and nitrogen cycle Primary SOL LS.6 The student will investigate and understand that organisms within an ecosystem are dependent on one another and on nonliving components of the environment. Key concepts include a) the carbon, water, and nitrogen cycles; b) interactions resulting in a flow of energy and matter throughout the system; c) complex relationships within terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems; and d) energy flow in food webs and energy pyramids. Related SOL LS.5 The student will investigate and understand the basic physical and chemical processes of photosynthesis and its importance to plant and animal life. Key concepts include b) transformation of water and carbon dioxide into sugar and oxygen. c) photosynthesis as the foundation of virtually all food webs. Background Information Matter has been on the Earth since it was formed billions of years ago. It is used over and over again in cycles. Each type of matter has its own cycle. In cycles, matter moves through living organisms and the environment. Materials Poster paper Markers Magazines Scissors Tape Glue Copies of attached labels for posters of the three cycles of nature Vocabulary carbon, combustion, condensation, cycle, decomposition, elements, evaporation, ground water, nitrogen, photosynthesis, precipitation, recycle, respiration, water Student/Teacher Actions (what students and teachers should be doing to facilitate learning) 1. Discuss with the class the carbon cycle, water cycle, and nitrogen cycle. Video clips from Internet resources may be used to demonstrate the three cycles. -

Ecological Succession and Biogeochemical Cycles

Chapter 10: Changes in Ecosystems Lesson 10.1: Ecological Succession and Biogeochemical Cycles Can a plant really grow in hardened lava? It can if it is very hardy and tenacious. And that is how succession starts. It begins with a plant that must be able to grow on new land with minimal soil or nutrients. Lesson Objectives ● Outline primary and secondary succession, and define climax community. ● Define biogeochemical cycles. ● Describe the water cycle and its processes. ● Give an overview of the carbon cycle. ● Outline the steps of the nitrogen cycle. ● Understand the phosphorus cycle. ● Describe the ecological importance of the oxygen cycle. Vocabulary ● biogeochemical cycle ● groundwater ● primary succession ● carbon cycle ● nitrogen cycle ● runoff ● climax community ● nitrogen fixation ● secondary succession ● condensation ● phosphorus cycle ● sublimation ● ecological succession ● pioneer species ● transpiration ● evaporation ● precipitation ● water cycle Introduction Communities are not usually static. The numbers and types of species that live in them generally change over time. This is called ecological succession. Important cases of succession are primary and secondary succession. In Earth science, a biogeochemical cycle or substance turnover or cycling of substances is a pathway by which a chemical substance moves through both biotic (biosphere) and abiotic (lithosphere, atmosphere, and hydrosphere) compartments of Earth. A cycle is a series of change which comes back to the starting point and which can be repeated. The term "biogeochemical" tells us that biological, geological and chemical factors are all involved. The circulation of chemical nutrients like carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, phosphorus, calcium, and water etc. through the biological and physical world are known as biogeochemical cycles. In effect, the element is recycled, although in some cycles there may be places (called reservoirs) where the element is accumulated or held for a long period of time (such as an ocean or lake for water). -

The Water Cycle (PDF)

SEA LAB~ MARINE SCIENCE EDUCATION CENTER New Bedford Public Schools 838 South Rodney French Boulevard - New Bedford, MA 02744 The Water Cycle Concept: The water cycle is the continuous process of water evaporating, becoming cooled and condensing, and then returning to the earth in the form of precipitation Objective: To become familiar with the processes of the water cycle through a unified arts approach Background Knowledge: Water in the oceans covers about 71 % of the earth's surface. It must also be remembered that a great deal of water is present in a solid state in the form of ice at the poles. Water vapor is present in our atmosphere. Because of its great abundance on the earth's surface, water is an important weather factor. Heat energy from the sun warms the surface of our planet. Water molecules at the surface of bodies of water absorb heat and, with increased energy, may escape into the air as water vapor. This transformation of a liquid to a gas is called evaporation. The water vapor near the earth's surface is also warmed, and the absorbed energy causes the speeding up of the molecules. The molecules move up and away from the evaporation surface. The water vapor molecules rise into the air and cone into contact with areas of low pressure. The air expands and becomes cooler. Air may also be cooled by heat loss due to radiation. The water molecules collect and form minute droplets. This transition of a gas into a liquid is termed condensation. If the condensation occurs around tiny dust particles above the earth's surface, a cloud is formed. -

The Carbon Cycle

TEACHER GUIDE THE CARBON CYCLE MATERIALS PER GROUP: LESSON OVERVIEW: Activity 1 The carbon cycle is the biogeochemical cycle by which carbon is • Carbonated water (clear soda or exchanged among the biosphere, pedosphere, geosphere, hydro- seltzer water) sphere and atmosphere of Earth. Along with the nitrogen cycle • Hot water (50°C) and the water cycle, the carbon cycle comprises a sequence of • Cold water (5°C) events key to making Earth capable of sustaining life; it describes • Two 12 oz. plastic bowls the movement of carbon as it is recycled and reused throughout • Two small (3 oz.) clear plastic cups the biosphere. Activity 2 LESSON OBJECTIVES: • Vinegar Students will be able to: • Baking soda 1. Observe the density of carbon dioxide. • Universal indicator 2. Demonstrate the effect of temperature on the amount of car- • Water bon dioxide that will dissolve in water. • Water and indicator cup 3. Test the effect of carbon dioxide on the pH of water. • Baking soda and vinegar 4. Describe how these properties of carbon dioxide relate to the • Mini spoon carbon cycle. • Universal indicator pH color chart ESSENTIAL QUESTION: Activity 3 How does matter cycle through an ecosystem? • Bubble generator* • Dry ice (8 oz.) TOPICAL ESSENTIAL QUESTION: • 9 oz. plastic cup What is carbon’s role in life on Earth? • Water (enough to fill bubble generator half-full) • Plastic spoon TOTAL DURATION: • Dish soap (5 mL) 15-20 min. pre-lab prep time; 40-50 min. class time • Cotton glove SAFETY PRECAUTIONS: *A bubble generator can be purchased from • Avoid contact of all chemicals with eyes and skin. -

Slide 1 WATER: ESSENTIAL for LIFE • Unique Properties Allow Life

Slide 1 WATER: ESSENTIAL FOR LIFE • Unique properties allow life to exist on Earth: capillarity, adhesion & cohesion. • Universal biological solvent - medium for chemical reactions. • All organisms depend on water for movement of materials, and is necessary for maintenance, growth & reproduction. • Plants need water for photosynthesis, animals need plants for food. LIMITED SUPPLY • 70% of Earth covered with water. • Amount of fresh water is only about 1% of total • Freshwater contains less than .01% of salt. • Freshwater in unevenly distributed, much is in polar ice. • The distribution of civilizations arc affected by the availability of freshwater. • Water is a sustainable resource because of natural recycling. • Sea water is salty because rivers carry small amounts of salt to the oceans where the water evaporates, leaving the salt behind. PHYSICAL PROPERTIES • Maximum density at 4 deg. C (37 deg. F) allows for ice to float, bodies of water do not freeze solid. Adhesion (molecules stick to sides of container) and cohesion (molecules stick to each other) are responsible for capillarity which allows water in fine diameter tubes to flow upward, resisting gravity. Transpiration would not be possible without capillarity and evaporation. • Freezing occurs at 0 deg. C (32 deg. F) - changes phase from liquid to a solid, low kinetic energy of molecules, molecules packed closely together, heat energy has been removed. • Boiling occurs at 100 deg. C (212 deg. F) - changes phase from liquid to a gas (water vapor), highest kinetic energy of molecules, molecules are spaced farthest apart, heat energy has been added, boiling is rapid evaporation. • Liquid phase, water, has lower kinetic energy than water vapor but higher than ice. -

The Water Cycle

The Water Cycle What is the Water Cycle? The water cycle is a way that water moves all around the Earth. It never stops, it does not have a beginning or an end. It's like a big circle! Did you know? The water cycle is also known as the “hydrologic cycle” Earth has been recycling water for over 4 billion years! Do plants sweat? Well, sort of.... People perspire (sweat) and plants transpire. Transpiration is the process by which plants lose water out of their leaves. So how can we understand this magical process called the water cycle? There are four main parts to the water cycle: Evaporation, Convection, Precipitation and Collection. 1) Evaporation Evaporation is when the sun heats up water in rivers or lakes or the ocean and turns it into vapour or steam. The water vapour or steam leaves the river, lake or ocean and goes into the air. We have already learnt about transpiration, did you know that transpiration gives evaporation a bit of a hand in getting the water vapour back up into the air! 2) Convection Convection in the water cycle is when the air near the surface is heated, then rises taking heat with it. Water vapour in the air gets cold and changes back into liquid, forming clouds. This is called condensation. You can see the same sort of thing at home... Pour a glass of cold water on a hot day and watch what happens. Water forms on the outside of the glass. That water didn't somehow leak through the glass! It actually came from the air.