The Case of Small Hive Beetle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Small Hive Beetle a Serious New Threat to European Apiculture

68639_CENTSCILAB 6/4/03 20:48 Page 1 The Small Hive Beetle A serious new threat to European apiculture About this leaflet This leaflet describes the Small Hive Beetle (Aethina tumida), a potential new threat to UK beekeeping. This beetle, indigenous to Africa, has recently spread to the USA and Australia where it has proved to be a devastating pest of European honey bees. There is a serious risk of its accidental introduction into the UK. All beekeepers should now be aware of the fundamental details of the beetle’s lifecycle and how it can be recognised and controlled. 68639_CENTSCILAB 6/4/03 20:49 Page 2 Introduction: the small hive beetle problem The Small Hive Beetle, Aethina tumida It is not known how the beetle reached either (Murray) (commonly referred to as the 'SHB'), the USA or Australia, although in the USA is a major threat to the long-term shipping is considered the most likely route. sustainability and economic prosperity of UK By the time the beetle was detected in both beekeeping and, as a consequence, to countries it was already well established. agriculture and the environment through disruption to pollination services, the value of The potential implications for European which is estimated at up to £200 million apiculture are enormous, as we must now annually. assume that the SHB could spread to Europe and that it is likely to prove as harmful here The beetle is indigenous to Africa, where it is as in Australia and the USA. considered a minor pest of honey bees, and until recently was thought to be restricted to Package bees and honey bee colonies are that continent. -

Small Hive Beetle Management in Mississippi Authors: Audrey B

Small Hive Beetle Management in Mississippi Authors: Audrey B. Sheridan, Research/Extension Associate, Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology and Plant Pathology, Mississippi State University; Harry Fulton, State Entomologist (retired); Jon Zawislak, Department of Entomology, University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture, Cooperative Extension Service. Cover photo by Alex Wild, http://www.alexanderwild.com. Fig. 6 illustration by Jon Zawislak. Fig. 7 photo by Katie Lee. All other photos by Audrey Sheridan. 2 Small Hive Beetle Management in Mississippi CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 Where in the United States Do Small Hive Beetles Occur? .................................. 1 How Do Small Hive Beetles Cause Damage? .......................................................... 1 How Can Small Hive Beetles Be Located and Identifi ed in a Hive? .............................................................................................. 2 Important Biological Aspects of Small Hive Beetles ............................................. 5 Cleaning Up Damaged Combs ................................................................................ 8 Preventing Small Hive Beetle Damage in the Apiary ............................................ 9 Managing Established Small Hive Beetle Populations ....................................... 12 Protecting Honey Combs and Stored Supers During Processing .............................................................................................. -

Small Hive Beetle in Italy

Small hive beetle in Italy Epidemiological situation and surveillance 2018 PAFF Committee – Animal health and Welfare 25/26 February 2019 Small hive beetle in Italy from 2014 to 2017 2014 2016 2/10 Small hive beetle in Italy: outbreaks reported in 2018 Natural colonies Sentinel nucleus 3/10 Restriction zones and movements control From Calabria: total ban of movements of bees and bumble bees (hives, queen bees, package bees, bee for pollination) Surveillance zone: the remaining part of the Calabrian territory Protection zone: - Reggio Calabria Province - Vibo Valentia Province - Cosenza: 10km around outbreak 4/10 Surveillance: Calabria and Sicily Calabria: • In the protection zones (Reggio Calabria e Vibo Valencia) clinical control of sentinel nucleus. • In the surveillance zone random clinical controls on apiaries (2% prev 95% conf) Sicily: • random clinical control of apiaries (2% prev 95% conf); • control on sentinel nucleus (9) located along the sicilian border facing Calabria region • control on sentinel nucleus (3) around the only one outbreak confirmed in Siracusa Province (2014) • control on sentinel nucleus around 3 establishment for honey extraction 5/10 Surveillance: Calabria and Sicily (2018) Region Province N. positive apiaries N. negative apiaries N. positive sentinel nucleus N. negative sentinel nuclei CATANZARO 68/53 COSENZA 71/76 Calabria CROTONE 104/35 REGGIO CALABRIA 1* 1 4 27 VIBO VALENTIA 0 12 AGRIGENTO 9/19 CALTANISSETTA 20/20 CATANIA 81/84 6 ENNA 28/29 Sicily MESSINA 21/30 9 PALERMO 59/53 RAGUSA 21/29 SIRACUSA 34/51 TRAPANI 14/13 * Natural colony 6/10 Surveillance: rest of Italy randomly selected Selected on risk-based Three areas are identified on the national territory: - North Area: Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano, Valle d'Aosta, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Lombardy, Piedmont, Liguria and Emilia Romagna ; - Center Area: Tuscany, Marche, Lazio, Abruzzo and Molise; - South Area: Campania, Basilicata, Puglia and Sardinia. -

Small Hive Beetle

State of Hawai‘i New Pest Advisory DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE No. 12-01 Issued January 2012 Small Hive Beetle Aethina tumida Murray (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae) Jacqueline D. Robson Figure 1: Adult small hive beetle (approx. 3/16” or 5mm) Introduction. In April 2010, a beekeeper in Egypt (2000), Australia (2001), Canada (2002), Pana‘ewa, on the Big Island, contacted Portugal (2004), Mexico (2007) and Hawai‘i HDOA’s entomologist in Hilo about beetles he (2010). In Hawai‘i, SHB is currently widely had found inside his hives. The entomologist distributed on both O‘ahu and the Big Island. It collected four beetles and together with HDOA was also detected on Moloka‘i and Maui in entomologists in Honolulu, made a preliminary 2011 but widespread reports have not yet identification of small hive beetle (SHB). This occurred. was confirmed on April 30, 2010 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Identification Service in Riverdale, MD. Description. Adult SHB are brown on emergence, changing to black after a few days. Beetles are oval shaped and are approximately 3/16 inch long. In the hive, they run quickly and avoid light. Larvae are off- white and elongated with 2 rows of spines running the length of their dorsal side - they grow to a length of approximately 7/16 inch before pupation. SHB larvae crawl out of the hive and drop to the soil beneath to pupate. Although SHB prefers to live with honey bees, it can also complete its life cycle on several types of fruit found locally. Figure 2. Small hive beetle adults and larvae feeding on honey comb. -

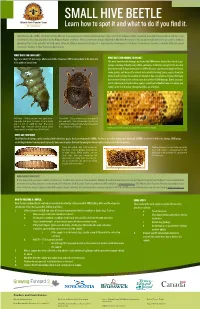

SMALL HIVE BEETLE Learn How to Spot It and What to Do If You Find It

SMALL HIVE BEETLE Learn how to spot it and what to do if you find it. Small hive beetle (SHB), Aethina tumida Murray, is an invasive pest of western honey bees (Apis mellifera Linnaeus) that originated from Sub-Saharan Africa and has since established a breeding population in the Niagara Region of Ontario. Hives from Ontario may be imported to Maritime Provinces in the spring for pollination of crops such as lowbush blueberry. Due to the potential for SHB entry, either by flight or movement of hives, it is important that beekeepers at all levels of experience be able to identify SHB and report suspicious findings to their Provincial Apiculturist. WHAT DOES SHB LOOK LIKE? Eggs are small (1.5 mm long), white and visible. However, SHB is more likely to be detected WHAT DOES SHB DAMAGE LOOK LIKE? in its adult or larval form. The most considerable damage performed by SHB occurs during their larval stage. Larvae consume virtually every edible substance in the hive except for the wooden hive-ware itself. A large infestation of SHB will cause significant damage to brood, comb, pollen, and honey. Excrement defecated by feeding larvae causes honey to ferment and no longer be suitable for human or bee consumption. Frames that have been removed from active colonies are also at risk of SHB damage. Entire seasons’ worth of honey in extraction lines can be spoiled and valuable frames of empty wax comb can be lost if indoor storage facilities are infested. SHB larva – SHB larvae are small, pale, worm- Adult SHB – Adults measuring an average 5.5 like grubs that grow to almost 1 cm in length mm long and 3.2 mm wide emerge from the soil and 1.3 mm in width by their final larval as light brown and eventually fade to black (Lyle growth stage. -

The Small Hive Beetle a Serious New Threat to European Apiculture

The Small Hive Beetle A serious new threat to European apiculture About this leaflet This leaflet describes the Small Hive Beetle (Aethina tumida), a potential new threat to UK beekeeping. This beetle, indigenous to Africa, has recently spread to the USA and Australia where it has proved to be a devastating pest of European honey bees. There is a serious risk of its accidental introduction into the UK. Introduction: the small hive beetle problem The Small Hive Beetle, Aethina tumida It is not known how the beetle reached either (Murray) (commonly referred to as the 'SHB'), the USA or Australia, although in the USA is a major threat to the long-term shipping is considered the most likely route. sustainability and economic prosperity of UK By the time the beetle was detected in both beekeeping and, as a consequence, to countries it was already well established. agriculture and the environment through disruption to pollination services, the value of The potential implications for European which is estimated at up to £200 million apiculture are enormous, as we must now annually. assume that the SHB could spread to Europe and that it is likely to prove as harmful here The beetle is indigenous to Africa, where it is as in Australia and the USA. considered a minor pest of honey bees, and until recently was thought to be restricted to that continent. However, in 1998 it was Could the SHB reach the UK? detected in Florida and it is now widespread Yes it could. There is a serious risk that the in the USA. -

The Small Hive Beetle, Aethina Tumida

SP 594 Agricultural Extension Service The University of Tennessee TheThe SmallSmall HiveHive BeetleBeetle -- aa NewNew PestPest ofof HoneyHoney BeesBees -- Detection: Colonies should be John A. Skinner, Associate Professor, and J. Patrick Parkman, carefully inspected for signs of Extension Assistant, Entomology and Plant Pathology infestation. Adult beetles run across the comb when the hive is first he small hive beetle, Aethina easily disperse to new honey bee colonies opened; and they are often discovered T tumida Murray, a new pest of to lay eggs. underneath the hive cover. To detect honey bees, was discovered damaging Beetles are most likely to be found in adults in the top hive body, place the honey bee colonies in Florida in spring of colonies that have been weakened by cover, inverted, on the top of an 1998. It is native to South Africa. When some other factor, usually mites. Larvae adjacent hive. Place the top hive body and how it arrived in North America are are most damaging because they feed on in the cover. Beetles will move unknown; however, the earliest known honey, stored pollen and bee brood. As downward away from the light. After a collection was made in 1996 in Charles- they feed, brood and honey combs are few minutes, lift the hive body to ton, SC. By 1999 it was established in damaged, especially as the larvae burrow check for beetles in the cover. To Florida, Georgia and North and South through them. Larvae defecate in the detect beetles on the bottom board, Carolina. In 2000, it was discovered in honey, causing it to ferment and bubble another area where adults normally Alabama, Ohio, Maine, Michigan, South out of the cells. -

Small Hive Beetle (SHB)

SMALL HIVE BEETLE (Aethina tumida) Small Hive Beetle (SHB) Description Adult SHB are about 1/4 in. in length and are reddish brown to dark brown in color. They move very quickly throughout the hive and can often be found in tight, dark spaces throughout the hive equipment. Adult bee- tles have developed the ability simulate the mouth parts of worker bees and will beg for food. This trait allows them to survive in the hive for extended periods of time. Photo credit: http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/misc/bees/small_hive_beetle.htm Small hive beetle larvae are long, cream- colored grubs and can reach a maximum length of 1/2 in. during the final instar. They have three pairs of well-developed prolegs and a series of dorsal spines. Photo credit: https://articles.extension.org/pages/60425/managing-small-hive-beetles Symptoms Economic damage from SHB occurs when the colony is unable to defend against the beetles. Damage from SHB includes: • Fermentation of honey from beetle feces (renders honey inedible) • Predation of bee eggs and brood by both larvae and adult SHB • Stored honey supers are extremely sus- ceptible to damage because no bees are present to protect the honey • Large numbers of SHB can result in the Photo credit: http://www.ars.usda.gov/Research/docs.htm? stoppage of egg laying by the queen and the colony absconding from the hive SMALL HIVE BEETLE (Aethina tumida) Life Cycle Adult small hive beetles become fertile about one week after emerging from the soil (where they pupate). When ready to reproduce, adult female SHB will oviposit directly into brood comb, pollen, or cracks and crevices within the hive. -

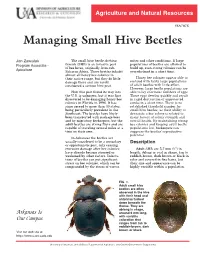

Managing Small Hive Beetles

Agriculture and Natural Resources FSA7075 Managing Small Hive Beetles Jon Zawislak The small hive beetle Aethina mites and other conditions. If large Program Associate tumida (SHB) is an invasive pest popu lations of beetles are allowed to of bee hives, originally from sub- build up, even strong colonies can be Apiculture Saharan Africa. These beetles inhabit overwhelmed in a short time. almost all honey bee colonies in their native range, but they do little Honey bee colonies appear able to damage there and are rarely contend with fairly large populations considered a serious hive pest. of adult beetles with little effect. However, large beetle populations are How this pest found its way into able to lay enormous numbers of eggs. the U.S. is unknown, but it was first These eggs develop quickly and result discovered to be damaging honey bee in rapid destruction of unprotected colonies in Florida in 1998. It has combs in a short time. There is no since spread to more than 30 states, established threshold number for being particularly prevalent in the small hive beetles, as their ability to Southeast. The beetles have likely devastate a bee colony is related to been transported with package bees many factors of colony strength and and by migratory beekeepers, but the overall health. By maintaining strong adult beetles are strong fliers and are bee colonies and keeping adult beetle capable of traveling several miles at a populations low, beekeepers can time on their own. suppress the beetles’ reproductive potential. In Arkansas the beetles are usually considered to be a secondary Description or opportunistic pest, only causing 1 excessive damage after bee colonies Adult SHB are 5-7 mm ( ⁄4") in have already become stressed or length, oblong or oval in shape, tan to weakened by other factors. -

Report on the National Stakeholders Conference on Honey Bee Health National Honey Bee Health Stakeholder Conference Steering Committee

United States Department of Agriculture Report on the National Stakeholders Conference on Honey Bee Health National Honey Bee Health Stakeholder Conference Steering Committee Sheraton Suites Old Town Alexandria Hotel Alexandria, Virginia October 15–17, 2012 National Honey Bee Health Stakeholder Conference Steering Committee USDA Office of Pest Management Policy (OPMP) David Epstein Pennsylvania State University, Department of Entomology James L. Frazier USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) Mary Purcell-Miramontes USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) Kevin Hackett USDA Animal and Plant Health and Inspection Service (APHIS) Robyn Rose USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Terrell Erickson U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) Thomas Moriarty Thomas Steeger Cover: Honey bee on a sunflower. Photo courtesy of Whitney Cranshaw, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org. Disclaimer: This is a report presenting the proceedings of a stakeholder conference organized and conducted by members of the National Honey Bee Health Stakeholder Conference Steering Committee on October 15-17, 2012 in Alexandria, VA. The views expressed in this report are those of the presenters and participants and do not necessarily represent the policies or positions of the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), or the United States Government (USG). iii Executive Summary After news broke in November 2006 about Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), a potentially new -

Journeyman Level Master Beekeepinjg Course

JOURNEYMAN LEVEL MASTER BEEKEEPINJG COURSE April 7, 2014 Class No. Four HONEY BEE PESTS AND DISEASE TRACHEAL MITE (Acarapis Woodi) Mites that infest the tracheae (breathing tubes) of honey bees were found in the U.S. for the first time in July, 1984 on the U.S. – Mexican border. It is microscopic in size. Female tracheal mite is looking for a newly emerged bee about 3 days old or less, whose exoskeleton’s odor is different from an older bees. She will transfer to the host and go into the first thoracic trachea. If she cannot find a host, she will crawl off and die. Grease patties causes all the bees to smell or have the odor like that of an older bee, which the tracheal mite does not like. Chemical control of the tracheal mite is done with Mitathol which has menthol in it. If the temp is too great, it will run the bees out of the hive. The Mitathol needs to be put on the bottom, if the temp is too high, greater than 85 degrees. The adults pierce the trachea and suck blood (hemolymph) from the bee. They live 30 or 40 days. Hive Treatment--Apply grease patties, one in the fall of the year (early Oct) and one in the spring (early march). Two parts sugar; one part Crisco. Tracheal Mites Tracheal mites are microscope mites which reproduce in the trachea (airways) of the bee. A visual aid that would suspect tracheal mites would be a large number of bees walking about the outside of the hive. -

Integrated Hive Management for Colorado Beekeepers Dr

Integrated Hive Management for Colorado Beekeepers Dr. Arathi Seshadri and Thia Walker Strategies for Identifying and Mitigating Pests and Diseases Affecting Colorado’s Honey Bees BIOAGRICULTURAL SCIENCES & PEST MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT 2nd Edition Integrated Hive Management for Colorado Beekeepers: Strategies for Identifying and Mitigating Pests and Diseases Affecting Colorado Honeybees. 2nd Edition*, December 2019. *1st edition originally published July 2014 Contact Information: Dr. Arathi Seshadri Thia Walker Research Entomologist Colorado State University Extension [email protected] Specialist-Pesticide Safety Education Invasive Species & Pollinator Health [email protected] Research Unit Colorado Environmental Pesticide USDA/ARS/WRRC Education Program (CEPEP) https://cepep.agsci.colostate.edu/ Acknowledgments: • With special thanks to Debra Newman for her assistance with layout and Rob Snyder of Bee Informed Partnership for his photos and recommendations. • The following individuals are gratefully acknowledged for their reviewing this publication and for their valuable suggestions: Al Summers, ichibanenterprises.org (Contributing Editor, 1st Edition) Peg Perreault, EPA Region 8 • Front and Back Cover Photo Credit: Lisa Mason, CSU Extension All other photo credits are listed individually. This 2nd edition of the publication was developed under Assistance Agreement No. E-96843601-0 awarded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 8. It has not been formally reviewed by EPA. The views expressed are solely those of the authors and EPA does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned. This guide is for educational purposes only. Mention of a specific product is only for illustrative purposes and should not be interpreted as an endorsement, nor should failure to mention a product be considered a criticism.