Interview with Clare Mallory Millikan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Everest Expeditions 1921, 1922 & 1924

Mount Everest Expeditions 1921, 1922 & 1924 A selection of books and ephemera from stock Meridian Rare Books Telephone: +44 (0)20 8694 2168 PO Box 51650 Email: [email protected] London www.meridianrarebooks.co.uk SE8 4XW VAT Reg. No.: GB 919 1146 28 United Kingdom Our books are collated in full and our descriptions aim to be accurate. We can provide further information and images of any item on request. If you wish to view an item from this catalogue, please contact us to make suitable arrangements. All prices are nett pounds sterling. VAT will be charged within the UK on the price of any item not in a binding. Postage is additional and will be charged at cost. Any book may be returned if unsatisfactory, in which case please advise us in advance. The present catalogue offers a selection of our stock. To receive a full listing of books in your area of interest, please enquire. Title-page image: Item 10 (detail) ©Meridian Rare Books 2021 1 Heron, A. M. ‘Geological Results of the Mount Everest Reconnaissance Expedi- tion.’ An article in Records of the Geological Survey of India, Vol. LIV, Part 2, 1922. Calcutta: the Geological Survey of India, 1922. £65 First edition. 8vo. pp. [x, list of publications], [129]-239, [x, list of publications]; 5 plates from photos., one folding map and one section relating to Heron’s article, one other map; good in the original printed wrappers, bumped to extremities. Not in S&B. Heron joined the 1921 Everest Reconnaissance, surveying an area “of over 8000 square miles” in the Arun river drainage region in Tibet. -

Sheryl Falk: a Data Privacy Lawyer & Mount Everest Climber

Free Speech, Due Process and Trial by Jury Sheryl Falk: A Data Privacy Lawyer & Mount Everest Climber Sheryl Falk at a memorial to perished Everest climbers By Natalie Posgate (Jan. 25) – It’s not very often that Sheryl Falk gets to slow Winston’s firmwide mentoring program targeted at down, turn off her phone and think in-depth about her helping young associates. She also informally mentors life. As co-leader of Winston & Strawn’s global privacy several associates at the firm. and data security task force, the Houston partner is always on the go – traveling almost every week, She was inspired to open this new chapter in her career speaking at various conferences and ending her nights while trekking in the shadow of Mount Pumori, which staying abreast of all her work emails. lies eight kilometers west of Mount Everest. Named after the daughter of George Mallory, the famed British But Falk recently had an off-the-grid opportunity when mountaineer who was a leading member of the first she traded two-and-a-half weeks of billable hours for few expeditions of Mount Everest, Pumori means her No. 1 bucket list item: making the climb to Everest “Mountain Daughter” in the Sherpa language. Base Camp. “The mountains are so tall and glorious that you’re Falk returned from the trek not only fulfilling a lifelong literally trekking in the shadow of giants,” Falk told The dream but also with a new career goal: help advance Texas Lawbook. more younger women attorneys. “As I was trekking I was just in gratitude – I’m living the Falk is now part of the faculty of the University of life of my dreams, I’ve accomplished everything I’ve Texas’s 2019 Women in Law Institute, a full-day wanted. -

The 1921 British Mount Everest Expedition Limited Edition Platinum Prints

The 1921 British Mount Everest Expedition Limited Edition Platinum Prints (1) ‘Monks and the Administrator at Shekar Tschöde Monastery.’ Photographer: Charles Kenneth Howard-Bury (1881-1963) Celluloid Negative, MEE21/0339 TO ORDER For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] The 1921 British Mount Everest Expedition Limited Edition Platinum Prints (2) ‘Members of Expedition at 17,300 ft. Camp.’ Top, left to right: Wollaston, Howard-Bury, Heron, Raeburn. Bottom, left to right: Mallory, Wheeler, Bullock, Morshead. Photographer: Alexander Frederick Richmond Wollaston (1875-1930) Celluloid Negative, MEE21/0396 TO ORDER For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] The 1921 British Mount Everest Expedition Limited Edition Platinum Prints (3) ‘A group of Bhutias, Linga.' Photographer: George Leigh Mallory (1886-1924) Celluloid Negative, MEE21/0587 TO ORDER For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] The 1921 British Mount Everest Expedition Limited Edition Platinum Prints (4) ‘The Abbot of Shekar Chote.’ Photographer: Charles Kenneth Howard-Bury (1881-1963) Celluloid Negative, MEE21/0327 TO ORDER For provenance and edition information please contact: [email protected] The 1921 British Mount Everest Expedition Limited Edition Platinum Prints (5) Above: Untitled. Photographer: George Leigh Mallory (1886-1924) Celluloid Negative, MEE21/0907 Below: ‘Looking down Arun Valley from slopes south of Shiling.’ Photographer: George Leigh Mallory (1886-1924) Celluloid Negative, MEE21/0641 -

The Wildest Dream: Conquest of Everest Educational Resources

THE WILDEST DREAM: CONQUEST OF EVEREST EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES GEORGE MALLORY’S HISTORIC 1924 ATTEMPT TO CLIMB MOUNT EVEREST—and the vast scientific and technological changes since his death—provide themes for compelling classroom activities in grades 4-12. Each activity below features film clips, maps, and photography from The Wildest Dream: Conquest of Everest and National Geographic’s collection of online articles and visuals. Educators can choose from a variety of standards-based activities for grades 4-8 and 9-12, to design a unique and engaging multi-disciplinary unit based on this fascinating mountain and its timeless allure for people around the world. Find activities, handouts, and media links to help students get the most out of The Wildest Dream at http://movies.nationalgeographic.com/movies/the-wildest-dream/educator-resources The Wildest Dream: GRADES 4-5, 6-8 ACTIVITIES Conquest of Everest Activity 1: Name that Destination Students hear clues about one of the Film Summary Grade 4-8 most desolate environments on Earth, then think about what they know and want to know about Mount Everest, the highest mountain on Earth. In 1999, renowned American mountaineer Conrad Anker made a discovery that Activity 2: Measuring Elevation, Students build an inclinometer, then use reverberated around the globe. High in Grade 6-8 Past and Present triangulation to measure the height of a tree. They compare their process to the Mount Everest’s “death zone,” he found the work of British surveyors in the 1800s. body of George Mallory—75 years after the British explorer mysteriously vanished Activity 3: Mapping the Shape Students build a model of a mountain Grade 4-5 of Everest and map its topography, then apply their during his attempt to become the first man learning to a topographic map of Mount to summit the world’s tallest peak. -

The Conquest of Everest

FILM REVIEWS ous power it can wield over men’s minds and tells the story of George Mallory who embarked on the fi rst British expedition to Mount Everest, never to return. In 1999, present-day mountaineer Conrad Anker (weirdly, a dead ringer for Aaron Eckhart) found Mallory’s frozen body, and his obsession with the British climber began. As a result, the fi lm interweaves extraordinary archive fi lm shot on Mal- lory’s fateful ascent with equally audacious modern-day footage of Anker’s attempt, with young British climber Leo Holding, to free-climb Everest’s infamous Second Step, just as Mallory tried to in 1924. WILDEST DREAM: The Himalayas are naturally cinematic THE CONQUEST OF EVEREST and the stunning aerial cinematography DIRECTOR ANTHONY GEFFEN gives the fi lm a majestic sweep, aided RELEASED SEPTEMBER 10TH by Liam Neeson’s powerful narration. CERT TBC However, The Wildest Dream draws its true NATIONAL GEOGRAPHICAL ENTERTAINMENT emotional power from the correspondence THE SECRET IN THEIR EYES As the highest point on Earth, Mount Ever- between Mallory and his wife Ruth, read DIRECTOR JUAN JOSE CAMPANELLA est has a dangerous allure, especially for by Ralph Fiennes and the late Natasha RELEASED AUGUST 13TH those people brave, or foolish, enough to Richardson, which demonstrates the depth CERT 18 climb it. of their love, but also the fatal power of his METRODOME The Wildest Dream is a fascinating obsession. Richly deserving of this year’s best foreign documentary that explores the danger- 7/10 BEN STEVENS language Oscar, this impeccably crafted Argentinean trawl through the human condi- tion draws its audience in and never lets go until the closing frame. -

My Experience on Mt. Everest. John All

My Experience on Mt. Everest. John All This narrative describes my climb of the North Col/North Ridge Route on Mt. Everest and is selections from my journal of the climb. This route is accessed through Tibet and is the one attempted by George Mallory and various British teams prior to World War II. It was closed to climbing after the Chinese invasion of Tibet and only re-opened in the late 1970’s. It is one of the two main climbing routes used today – the other being the southern route that Hillary and Norgay used for the first ascent of the mountain in 1953. The Hillary route begins in Nepal and is by far the easier and safer of the two. Currently, if you summit from North side, there is a 5% chance you will not survive the descent. In 2010, there were approximately 150 people who attempted the climb from Tibet. Approximate 50 people summitted and 7 people died that we know of (expeditions leave the bodies on the mountain and will not talk about deaths because it hurts their reputation, so those are only what we know about from talking to the Sherpas), thus this year was almost a 15% summit death rate. Be careful what you wish for… The first three days of the route are spent ascending the East Rongbuk glacier, but I do not talk about that long slog through loose rock and seracs or the time spent at 5200 meters and 6400 meters acclimatizing other than to say: It feels like you have a lead suit on your body every minute. -

Original Photographs from the Legendary First Ascent PDF Book Jul 25, Randall Rated It Really Liked It

THE CONQUEST OF EVEREST: ORIGINAL PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE LEGENDARY FIRST ASCENT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK George Lowe,Huw Lewis-Jones | 240 pages | 15 May 2013 | Thames & Hudson Ltd | 9780500544235 | English | London, United Kingdom The Conquest of Everest: Original Photographs from the Legendary First Ascent PDF Book Jul 25, Randall rated it really liked it. Continue to browse in english. Alfred Gregory. The expedition's cameraman, Tom Stobart , produced a film called The Conquest of Everest , which appeared later in [53] and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature. Retrieved 21 June You May Also Like. Michael Ward. The photography is a true step into their world and humbles you to behold it' Photography Monthly 'The photographs are stunning and, in many cases, moving' Financial Times. The following year, Lowe went with them to Nepal as a member of the expedition to Cho Oyu aiming to explore physiology and oxygen flow rates. Illustrations: The mountaineers were accompanied by Jan Morris known at the time under the name of James Morris , the correspondent of The Times newspaper of London, and by porters , so that the expedition in the end amounted to over four hundred men, including twenty Sherpa guides from Tibet and Nepal, with a total weight of ten thousand pounds of baggage. Which being interpreted meant: "Summit of Everest reached on May 29 by Hillary and Tenzing" John Hunt at Base Camp had lost hope that news of the successful ascent would reach London for the Coronation, and they listened with "growing excitement and amazement" when it was announced on All India Radio from London on the evening of 2 June, the day of the Coronation. -

George Mallory and Francis Urquhart

230 T HE A LPINE J OURN A L 2 0 1 7 to such lengths to secure the property rights of enemy aliens. Then again, perhaps this emphasis on rights and the rule of law is exactly what the STEPHEN GOLDING & PETER GILLMAN Allied and Indian forces were fighting for. Shipton’s Travellers file provides us with a rare glimpse of the British imperial security state at both its most effective and at its most banal and pettifogging. The same imperial security George Mallory and Francis apparatus that maintained such tight control over the trans-Himalaya border regions was also seemingly unable to track down and locate one of its own Urquhart: an Academic Friendship across all of its various agencies in wartime. Shipton’s Travellers file sheds further light about the ways in which he sought to negotiate access to the politically controlled border zone of British India, providing us with many more tantalizing details of his movements and motivations. It reveals, for the first time, his concerted efforts to explore in the remote regions of west- ern Tibet and the power of British India’s border cadres to deny access to anyone whose interest did not align directly with those of the Government of India. It somehow seems appropriate then that Shipton’s Travellers file ends with the India Office awaiting a reply from Shipton, a reply one sus- pects that never came. Given to reticence, Shipton in the archive is elusive, always on the move, as befits a traveller. You have to wonder: if the Govern- ment of India couldn’t find Shipton and get a reply from him, what hope has the modern historian or biographer got of finally tracking him down? George Mallory was a keen oarsman, here rowing with Balliol College members at Sandford on the Thames, 1 May 1911. -

The Economics of Innovation: Mountaineering and the American Space Program

The Economics of Innovation: Mountaineering and the American Space Program Howard E. McCurdy May, 2013 1 “The Economics of Innovation: Mountaineering and the American Space Program,” a research report submitted by Howard E. McCurdy, Ph.D., School of Public Affairs, American University, 4400 Massachusetts Ave. N.W., Washington, D.C., 20016, in fulfillment of NASA contract NNX12AQ63G, 11 March 2013; revised and resubmitted, 18 May 2013. Following page: An expedition 8 crewmember on the International Space Station took this photograph of Mt. Everest in 2004. Mt. Everest is 29,035 feet high. Passengers in a commercial jetliner flying over Everest at an altitude of 35,000 feet would be too close to the mountain to experience this view. The photograph is taken from the north. In the foreground appears the Tibetan plateau. To the south, clouds cover much of Nepal. Everest is the darker mountain peak to center right with the perennial cloud plume. The first expeditions attempting to climb the mountain approached from Tibet, traveling up the Rongbuk glacier, turning east, then moving back toward the Vshaped spot below and to the left of the summit. That is the North Col, a low point between Everest and Changtse. From the North Col, climbers proceed up the north ridge to its junction with the windswept northeast ridge and from there toward the summit. Most commercial outfitters approach the Everest from Nepal on the mountain’s southern side. This route follows the Western Cwm, visible as the deep cut stretching out to the right of the mountain. Upon reaching the South Col (behind Everest in this photograph), climbers turn north and head directly toward the space station. -

Sherpas and Their Dangerous Job on Mt. Everest

Sherpas and Their Dangerous Job on Mt. Everest The last cleft in the Khumbu Icefall before the Western Cwm (pronounced “coom”), in April 2005. Photo by Olaf Rieck. LICENSE: CC BY 2.5 Expert mountain climbers know that a river of ice, called the Khumbu Icefall, is an extremely dangerous place to cross on Mt. Everest. Measuring about a half-mile, this constantly shifting glacier has deep crevasses which can open (or close) in a day (or less). George Mallory, the famous British mountain climber, turned away from Khumbu when he saw it in 1921. It was, he said, impossible to cross. Since then, other mountain climbers have successfully conquered the icefall, but the place is more than intimidating. Its overhanging ice can be 10-stories high. Climbers use ropes which can snap and ladders which may not stay in place. After all, moving ice means the ladders have no stable place on which to rest. Glaciers—on the icefall or the Western Ridge of the mountain—can break away at any time. If that happens, avalanches could follow. An avalanche can trigger a catastrophe, with tons of ice set free to harm people. If climbers ascend Everest by means of one of the established routes, they must pass through Khumbu Icefall. It is situated between the Base Camp and Camp 1 on the South Col route to the summit. In April of 2014, thirteen Sherpas died in this notoriously dangerous part of Everest (located on the south side of the world's highest peak). Several more were injured, and three were missing (presumed dead), after an avalanche broke loose, falling from the hanging glaciers along the West Shoulder. -

The Politics of Totemic Sporting Heroes and the Conquest of Everest

Paul Gilchrist: The politics of totemic sporting heroes and the conquest of Everest The politics of totemic sporting heroes and the conquest of Everest Paul Gilchrist University of Brighton, [email protected] ABSTRACT This article prepares the conceptual ground for understanding the sporting hero. It focuses upon the totemic logic of the sporting hero; the social, cultural and political conditions that bring the hero into being. This position is elaborated through a review of an interdisciplinary literature and a discussion of the British sporting hero. In particular, the essay focuses upon ideas and legacies of the heroic that have emerged through attempts to conquer Everest, as a heightened symbolic site for the continued generation of British imperial aspirations and heroic masculinities. It culminates with an examination of Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, who in 1953 ascended Everest, but whose case is illustrative of the powerful associations suggested by the totemic approach. However, Norgay’s ex- ample is also used as a reminder of the assumed relationships and associations between the hero and society. It cautions that we balance continuities and complexities in future studies of the sporting hero, and that we remain sensitive to the constructedness of the sporting hero, experienced through history and by collectives and individuals. KEYWORDS: sporting hero, masculinity, British imperialism, Everest, mountaineering Introduction Along one wall in St. Wilfrid’s parish church in Mobberley, Cheshire, England, is a stained-glass window devoted to the memory of George Leigh Mallory—the English- man who, with Sandy Irvine, made a last effort for the summit of Everest in 1924, but disappeared into the clouds, never to be seen by his comrades again. -

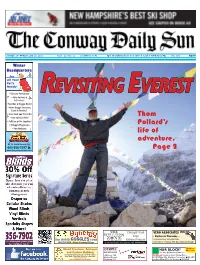

Revisiting Everest Revisiting Everest

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2016 VOL. 28 NO. 21 CONWAY, N.H. MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY’S DAILY NEWSPAPER 356-3456 FREE Winter Headquarters ...for All Your Pet’s Needs! • Visit our Pet Bakery! REEVISITINGVISITING EVVERESTEREST • Gifts for Pets & Pet Lovers! • Paw Wax & Doggie Boots! • Warm Doggie Sweaters, Coats & Hoodies! • Crate Pads and Pet Beds! Thom • Paw Safe Ice Melt! • Full Line of Pet Supplies! • 4 Doggie Playgroups Pollard’s • Pets Welcome life of adventure. Rt. 16, North Conway, NH 603-356-7297 Page 2 www.fouryourpawsonly.com Therapy Pool VENO ASSOCIATES Yoga – Dealer in Firearms – Over 1000 Ski GOGGLES in stock Infrared Sauna 603-986-9516, 207-935-7583 603-356-5039 • North Conway Village at The Snowflake Inn, Jackson, NH 603-383-8259 84 Smith St., Fryeburg, ME. Open daily and by appt. Walk-ins Wood Creations, Antiques ® OSSIPEE H&R BLOCK Welcome and Custom Building 603-539-2020 Get Your Billion Back America. Red Barn Shopping Center, Rt. 16, North Conway 250 Route 16B New Location: Willow Place Mon–Weds. 10am–5pm, Thurs–Sat. 10am–6pm We Moved! Sundays 10am–5pm (Indian Mound 1857 White Mtn. Highway, N.Conway 356-8907 See our ad inside for more details Shopping Ctr) Indian Mound Plz, Ctr. Ossipee 539-2220 Page 2 — THE CONWAY DAILY SUN, Saturday, February 20, 2016 Thom Pollard’s excellent adventures Jackson climber to make third assault on Everest BY TOM EASTMAN THE CONWAY DAILY SUN CONWAY — Why climb Everest? Well, to quote late climber Sir George Mallory (1886-1924), “Because it’s there.” But for award-winning Jackson documentary fi lmmaker Thom Pollard, it’s not just about the mountain; it’s also because of what’s there inside a climber’s heart and soul.