Mathematical Statistics in 20Th-Century America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematical Statistics

Mathematical Statistics MAS 713 Chapter 1.2 Previous subchapter 1 What is statistics ? 2 The statistical process 3 Population and samples 4 Random sampling Questions? Mathematical Statistics (MAS713) Ariel Neufeld 2 / 70 This subchapter Descriptive Statistics 1.2.1 Introduction 1.2.2 Types of variables 1.2.3 Graphical representations 1.2.4 Descriptive measures Mathematical Statistics (MAS713) Ariel Neufeld 3 / 70 1.2 Descriptive Statistics 1.2.1 Introduction Introduction As we said, statistics is the art of learning from data However, statistical data, obtained from surveys, experiments, or any series of measurements, are often so numerous that they are virtually useless unless they are condensed ; data should be presented in ways that facilitate their interpretation and subsequent analysis Naturally enough, the aspect of statistics which deals with organising, describing and summarising data is called descriptive statistics Mathematical Statistics (MAS713) Ariel Neufeld 4 / 70 1.2 Descriptive Statistics 1.2.2 Types of variables Types of variables Mathematical Statistics (MAS713) Ariel Neufeld 5 / 70 1.2 Descriptive Statistics 1.2.2 Types of variables Types of variables The range of available descriptive tools for a given data set depends on the type of the considered variable There are essentially two types of variables : 1 categorical (or qualitative) variables : take a value that is one of several possible categories (no numerical meaning) Ex. : gender, hair color, field of study, political affiliation, status, ... 2 numerical (or quantitative) -

This History of Modern Mathematical Statistics Retraces Their Development

BOOK REVIEWS GORROOCHURN Prakash, 2016, Classic Topics on the History of Modern Mathematical Statistics: From Laplace to More Recent Times, Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 754 p. This history of modern mathematical statistics retraces their development from the “Laplacean revolution,” as the author so rightly calls it (though the beginnings are to be found in Bayes’ 1763 essay(1)), through the mid-twentieth century and Fisher’s major contribution. Up to the nineteenth century the book covers the same ground as Stigler’s history of statistics(2), though with notable differences (see infra). It then discusses developments through the first half of the twentieth century: Fisher’s synthesis but also the renewal of Bayesian methods, which implied a return to Laplace. Part I offers an in-depth, chronological account of Laplace’s approach to probability, with all the mathematical detail and deductions he drew from it. It begins with his first innovative articles and concludes with his philosophical synthesis showing that all fields of human knowledge are connected to the theory of probabilities. Here Gorrouchurn raises a problem that Stigler does not, that of induction (pp. 102-113), a notion that gives us a better understanding of probability according to Laplace. The term induction has two meanings, the first put forward by Bacon(3) in 1620, the second by Hume(4) in 1748. Gorroochurn discusses only the second. For Bacon, induction meant discovering the principles of a system by studying its properties through observation and experimentation. For Hume, induction was mere enumeration and could not lead to certainty. Laplace followed Bacon: “The surest method which can guide us in the search for truth, consists in rising by induction from phenomena to laws and from laws to forces”(5). -

Mathematical Economics - B.S

College of Mathematical Economics - B.S. Arts and Sciences The mathematical economics major offers students a degree program that combines College Requirements mathematics, statistics, and economics. In today’s increasingly complicated international I. Foreign Language (placement exam recommended) ........................................... 0-14 business world, a strong preparation in the fundamentals of both economics and II. Disciplinary Requirements mathematics is crucial to success. This degree program is designed to prepare a student a. Natural Science .............................................................................................3 to go directly into the business world with skills that are in high demand, or to go on b. Social Science (completed by Major Requirements) to graduate study in economics or finance. A degree in mathematical economics would, c. Humanities ....................................................................................................3 for example, prepare a student for the beginning of a career in operations research or III. Laboratory or Field Work........................................................................................1 actuarial science. IV. Electives ..................................................................................................................6 120 hours (minimum) College Requirement hours: ..........................................................13-27 Any student earning a Bachelor of Science (BS) degree must complete a minimum of 60 hours in natural, -

Priorities for the National Science Foundation

December 2020 Priorities for the National Science Foundation Founded in 1888, the American Mathematical Society (AMS) is dedicated to advancing the interests of mathematical research and scholarship and connecting the diverse global mathematical community. We do this through our book and journal publications, meetings and conferences, database of research publications1 that goes back to the early 1800s, professional services, advocacy, and awareness programs. The AMS has 30,000 individual members worldwide and supports mathemat- ical scientists at every career stage. The AMS advocates for increased and sustained funding for the National Science Foundation (NSF). The applications The NSF supports more fundamental research in the of advances in mathematical sciences—and done at colleges and theoretical science, 2 universities—than any other federal agency. A signif- including theory of icant increase in Congressional appropriations would mathe matics, occur help address the effects of years of high-quality grant on a time scale that proposals that go unfunded due to limited funding. means the investment Those unmet needs continue. A 2019 National Science Board report3 stated that in fiscal year 2018, “approxi- is often hard to justify mately $3.4 billion was requested for declined proposals in the short run. that were rated Very Good or higher in the merit review process.” This accounts for about 5440 declined proposals at the NSF. The U.S. is leaving potentially transformative scientific research unfunded, while other countries are making significant investments. In the next section we give an overview of our two priorities. The second, and final section offers a discussion of existing funding mechanisms for mathematicians. -

Applied Time Series Analysis

Applied Time Series Analysis SS 2018 February 12, 2018 Dr. Marcel Dettling Institute for Data Analysis and Process Design Zurich University of Applied Sciences CH-8401 Winterthur Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 PURPOSE 1 1.2 EXAMPLES 2 1.3 GOALS IN TIME SERIES ANALYSIS 8 2 MATHEMATICAL CONCEPTS 11 2.1 DEFINITION OF A TIME SERIES 11 2.2 STATIONARITY 11 2.3 TESTING STATIONARITY 13 3 TIME SERIES IN R 15 3.1 TIME SERIES CLASSES 15 3.2 DATES AND TIMES IN R 17 3.3 DATA IMPORT 21 4 DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS 23 4.1 VISUALIZATION 23 4.2 TRANSFORMATIONS 26 4.3 DECOMPOSITION 29 4.4 AUTOCORRELATION 50 4.5 PARTIAL AUTOCORRELATION 66 5 STATIONARY TIME SERIES MODELS 69 5.1 WHITE NOISE 69 5.2 ESTIMATING THE CONDITIONAL MEAN 70 5.3 AUTOREGRESSIVE MODELS 71 5.4 MOVING AVERAGE MODELS 85 5.5 ARMA(P,Q) MODELS 93 6 SARIMA AND GARCH MODELS 99 6.1 ARIMA MODELS 99 6.2 SARIMA MODELS 105 6.3 ARCH/GARCH MODELS 109 7 TIME SERIES REGRESSION 113 7.1 WHAT IS THE PROBLEM? 113 7.2 FINDING CORRELATED ERRORS 117 7.3 COCHRANE‐ORCUTT METHOD 124 7.4 GENERALIZED LEAST SQUARES 125 7.5 MISSING PREDICTOR VARIABLES 131 8 FORECASTING 137 8.1 STATIONARY TIME SERIES 138 8.2 SERIES WITH TREND AND SEASON 145 8.3 EXPONENTIAL SMOOTHING 152 9 MULTIVARIATE TIME SERIES ANALYSIS 161 9.1 PRACTICAL EXAMPLE 161 9.2 CROSS CORRELATION 165 9.3 PREWHITENING 168 9.4 TRANSFER FUNCTION MODELS 170 10 SPECTRAL ANALYSIS 175 10.1 DECOMPOSING IN THE FREQUENCY DOMAIN 175 10.2 THE SPECTRUM 179 10.3 REAL WORLD EXAMPLE 186 11 STATE SPACE MODELS 187 11.1 STATE SPACE FORMULATION 187 11.2 AR PROCESSES WITH MEASUREMENT NOISE 188 11.3 DYNAMIC LINEAR MODELS 191 ATSA 1 Introduction 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose Time series data, i.e. -

Mathematical Statistics the Sample Distribution of the Median

Course Notes for Math 162: Mathematical Statistics The Sample Distribution of the Median Adam Merberg and Steven J. Miller February 15, 2008 Abstract We begin by introducing the concept of order statistics and ¯nding the density of the rth order statistic of a sample. We then consider the special case of the density of the median and provide some examples. We conclude with some appendices that describe some of the techniques and background used. Contents 1 Order Statistics 1 2 The Sample Distribution of the Median 2 3 Examples and Exercises 4 A The Multinomial Distribution 5 B Big-Oh Notation 6 C Proof That With High Probability jX~ ¡ ¹~j is Small 6 D Stirling's Approximation Formula for n! 7 E Review of the exponential function 7 1 Order Statistics Suppose that the random variables X1;X2;:::;Xn constitute a sample of size n from an in¯nite population with continuous density. Often it will be useful to reorder these random variables from smallest to largest. In reordering the variables, we will also rename them so that Y1 is a random variable whose value is the smallest of the Xi, Y2 is the next smallest, and th so on, with Yn the largest of the Xi. Yr is called the r order statistic of the sample. In considering order statistics, it is naturally convenient to know their probability density. We derive an expression for the distribution of the rth order statistic as in [MM]. Theorem 1.1. For a random sample of size n from an in¯nite population having values x and density f(x), the probability th density of the r order statistic Yr is given by ·Z ¸ ·Z ¸ n! yr r¡1 1 n¡r gr(yr) = f(x) dx f(yr) f(x) dx : (1.1) (r ¡ 1)!(n ¡ r)! ¡1 yr Proof. -

Mathematical and Physical Sciences

Overview of the Directorate for Mathematical and Physical Sciences NSF Grants Conference Hosted by George Washington University Arlington, VA, October 6-7, 2014 Bogdan Mihaila, [email protected] Program Director Division of Physics US Government NSF Vision and Goals Vision » A Nation that creates and exploits new concepts in science and engineering and provides global leadership in research and education Mission » To promote the progress of science; to advance the national health, prosperity, and welfare; to secure the national defense Strategic Goals » Transform the frontiers of science and engineering » Stimulate innovation and address societal needs through research & education » Excel as a Federal Science Agency NSF in a Nutshell Independent agency to support basic research & education Grant mechanism in two forms: » Unsolicited, curiosity driven (the majority of the $) » Solicited, more focused All fields of science/engineering Merit review: Intellectual Merit & Broader Impacts Discipline-based structure, some cross-disciplinary Support large facilities NSF Organization Chart Office of Diversity & National Science Board Director Inclusion (ODI) (NSB) Deputy Director Office of the General Counsel (OGC) Office of the NSB Office Office of International & Inspector General $482M (OIG) ($4.3M) Integrative Activities (OIIA) ($14.2M) Office of Legislative & Public Affairs (OLPA) Computer & Mathematical Biological Information Engineering Geosciences & Physical Sciences Science & (ENG) (GEO) Sciences (BIO) Engineering (MPS) (CISE) -

Kshitij Khare

Kshitij Khare Basic Information Mailing Address: Telephone Numbers: Internet: Department of Statistics Office: (352) 273-2985 E-mail: [email protected]fl.edu 103 Griffin Floyd Hall FAX: (352) 392-5175 Web: http://www.stat.ufl.edu/˜kdkhare/ University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 Education PhD in Statistics, 2009, Stanford University (Advisor: Persi Diaconis) Masters in Mathematical Finance, 2009, Stanford University Masters in Statistics, 2004, Indian Statistical Institute, India Bachelors in Statistics, 2002, Indian Statistical Institute, India Academic Appointments University of Florida: Associate Professor of Statistics, 2015-present University of Florida: Assistant Professor of Statistics, 2009-2015 Stanford University: Research/Teaching Assistant, Department of Statistics, 2004-2009 Research Interests High-dimensional covariance/network estimation using graphical models High-dimensional inference for vector autoregressive models Markov chain Monte Carlo methods Kshitij Khare 2 Publications Core Statistics Research Ghosh, S., Khare, K. and Michailidis, G. (2019). “High dimensional posterior consistency in Bayesian vector autoregressive models”, Journal of the American Statistical Association 114, 735-748. Khare, K., Oh, S., Rahman, S. and Rajaratnam, B. (2019). A scalable sparse Cholesky based approach for learning high-dimensional covariance matrices in ordered data, Machine Learning 108, 2061-2086. Cao, X., Khare, K. and Ghosh, M. (2019). “High-dimensional posterior consistency for hierarchical non- local priors in regression”, Bayesian Analysis 15, 241-262. Chakraborty, S. and Khare, K. (2019). “Consistent estimation of the spectrum of trace class data augmen- tation algorithms”, Bernoulli 25, 3832-3863. Cao, X., Khare, K. and Ghosh, M. (2019). “Posterior graph selection and estimation consistency for high- dimensional Bayesian DAG models”, Annals of Statistics 47, 319-348. -

Mathematical and Physical Sciences

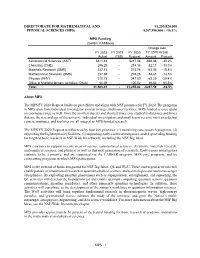

DIRECTORATE FOR MATHEMATICAL AND $1,255,820,000 PHYSICAL SCIENCES (MPS) -$247,590,000 / -16.5% MPS Funding (Dollars in Millions) Change over FY 2018 FY 2019 FY 2020 FY 2018 Actual Actual (TBD) Request Amount Percent Astronomical Sciences (AST) $311.16 - $217.08 -$94.08 -30.2% Chemistry (CHE) 246.29 - 214.18 -32.11 -13.0% Materials Research (DMR) 337.14 - 273.78 -63.36 -18.8% Mathematical Sciences (DMS) 237.69 - 203.26 -34.43 -14.5% Physics (PHY) 310.75 - 247.50 -63.25 -20.4% Office of Multidisciplinary Activities (OMA) 60.39 - 100.02 39.63 65.6% Total $1,503.41 - $1,255.82 -$247.59 -16.5% About MPS The MPS FY 2020 Request builds on past efforts and aligns with NSF priorities for FY 2020. The programs in MPS span from individual investigator awards to large, multi-user facilities. MPS-funded science spans an enormous range as well: from the smallest objects and shortest times ever studied to distances and times that are the size and age of the universe. Individual investigators and small teams receive most awards, but centers, institutes, and facilities are all integral to MPS-funded research. The MPS FY 2020 Request is influenced by four key priorities: (1) sustaining core research programs, (2) supporting the highest priority facilities, (3) supporting early-career investigators, and (4) providing funding for targeted basic research in NSF-Wide Investments, including the NSF Big Ideas. MPS continues to support its core areas of science (astronomical sciences, chemistry, materials research, mathematical sciences, and physics) as well as thet next generation of scientists. -

Brochure on Careers in Applied Mathematics

careers in applied mathematics Options for STEM Majors society for industrial and applied mathematics 2 / careers in applied mathematics Mathematics and computational science are utilized in almost every discipline of science, engineering, industry, and technology. New application areas are WHERE CAN YOU WHAT KINDS OF PROBLEMS MIGHT YOU WORK ON? constantly being discovered MAKE AN IMPACT? While careers in mathematics may differ widely by discipline while established techniques Many different types and job title, one thing remains constant among them— are being applied in new of organizations hire problem solving. Some potential problems that someone with ways and in emerging fields. mathematicians and mathematical training might encounter are described below. Consequently, a wide variety computational scientists. Which of them do you find most intriguing, and why? of career opportunities You can easily search the • How can an airline use smarter scheduling to reduce costs of are open to people with websites of organizations and aircraft parking and engine maintenance? Or smarter pricing mathematical talent and corporations that interest to maximize profit? training. you to learn more about their • How can one design a detailed plan for a clinical trial? Building such a plan requires advanced statistical skills and In this guide, you will find answers to sophisticated knowledge of the design of experiments. questions about careers in applied mathematics • Is ethanol a viable solution for the world’s dependence and computational science, and profiles on fossil fuels? Can biofuel production be optimized to of professionals working in a variety of combat negative implications on the world’s economy and environment? environments for which a strong background • How do we use major advances in computing power to in mathematics is necessary for success. -

Report of the MPSAC

Report of the Subcommittee of the MPSAC to Examine the Question of Renaming the Division of Mathematical Sciences James Berger (Duke University) Emery Brown (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Kevin Corlette (University of Chicago) Irene Fonseca (Carnegie Mellon University) Juan C. Meza (University of California – Merced) Fred Roberts (Rutgers University) (chair) Background Dr. Sastry Pantula, Director of the NSF Division of Mathematical Sciences, has proposed that the Division be renamed the Division of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences. In a letter to Dr. James Berger, chair of the MPSAC, the MPS Assistant Director Ed Seidel asked Dr. Berger to form a subcommittee to examine the question of renaming the Division of Mathematical Sciences at NSF. It included the following charge to the subcommittee: Charge The subcommittee will develop the arguments, both in favor of, and against, the suggestion of renaming the Division of Mathematical Sciences. In doing so, the scope of the subcommittee will include the following: • Seeking input from the mathematical and statistical societies within the U.S; • Seeking input from individual members of the community on this matter; and • Developing a document listing the arguments in favor of, and against, the suggestion. • And other comments relevant to this topic. In order to accept input from the public, MPS will arrange for creation of a website or email address to which the community may send its comments. Comments may be unsigned. While the subcommittee is not required to announce its meetings and hold them open to the public because it will be reporting directly to the MPSAC, any documents received by or created by the subcommittee may be subject to access by the public. -

Nonparametric Multivariate Kurtosis and Tailweight Measures

Nonparametric Multivariate Kurtosis and Tailweight Measures Jin Wang1 Northern Arizona University and Robert Serfling2 University of Texas at Dallas November 2004 – final preprint version, to appear in Journal of Nonparametric Statistics, 2005 1Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona 86011-5717, USA. Email: [email protected]. 2Department of Mathematical Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, Texas 75083- 0688, USA. Email: [email protected]. Website: www.utdallas.edu/∼serfling. Support by NSF Grant DMS-0103698 is gratefully acknowledged. Abstract For nonparametric exploration or description of a distribution, the treatment of location, spread, symmetry and skewness is followed by characterization of kurtosis. Classical moment- based kurtosis measures the dispersion of a distribution about its “shoulders”. Here we con- sider quantile-based kurtosis measures. These are robust, are defined more widely, and dis- criminate better among shapes. A univariate quantile-based kurtosis measure of Groeneveld and Meeden (1984) is extended to the multivariate case by representing it as a transform of a dispersion functional. A family of such kurtosis measures defined for a given distribution and taken together comprises a real-valued “kurtosis functional”, which has intuitive appeal as a convenient two-dimensional curve for description of the kurtosis of the distribution. Several multivariate distributions in any dimension may thus be compared with respect to their kurtosis in a single two-dimensional plot. Important properties of the new multivariate kurtosis measures are established. For example, for elliptically symmetric distributions, this measure determines the distribution within affine equivalence. Related tailweight measures, influence curves, and asymptotic behavior of sample versions are also discussed.