Devolution As a Threat to Democratic Decision-Making in Forestry? Findings from Three States in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Disaster Management Action Plan for the State of Uttarakhand

State Disaster Management Action Plan for the State of Uttarakhand Disaster Mitigation & Management Centre Uttarakhand Secretariat Rajpur Road, Dehradun-248001 1 INDE( C)APTER- I Introduction Page No. 1. Introduction 01 1.1 State Profile ,Social, Economic and Demographic 03 1.2 Demographic & Socio-economic Profile 03 1.3 Area & Administrative Divisions 04 1.4 Geology* 0. 1.5 Climate 06 1.6 Temperature 06 1.8 Literacy and Education 06 1.9 Health Infrastructure of Uttarakhand 08 1.10 Forests 10 1.11 Agriculture 10 1.12 Food Grain Production 11 1.13 Land Use Pattern 1 1.14 Industrial profile of Uttarakhand 1 1.15 Transport & Communication 14 1.16 Power & Electrical Installations 16 C)APTER- II 0ulnera1ility Analysis & Risk Analysis 2.1 Vulnerability Analysis 18 2.2 State Vulnerabilities 13 2.2.1 Vulnerabilities to Earthquakes 0 2.2.2 Earthquake Hazard Map 1- 2.3 Vulnerability to Landslides 3 2.3.1 Landslides Hazard Zonation Mapping 4 2.4 Vulnerability to Floods . 2.5.1 Cloudbursts 8 2.5.2 Flash Floods 8 2.6 Avalanches 3 2.7 Drought 3 2.8 Hailstorms 3 2 2.9 Socio-Economic Vulnerabilities 30 2.10 Economy & Lack of access to infrastructure 31 2.11 Education 3 2.12 High Mortality 3 2.13 Housing 3 2.14 Gender discrimination 34 2.15 People needing special care 34 2.16 Live Stocks 34 C)APTER- III Preventive Measures 3.1 Early Warning and Dissemination systems 36 3.2 State Emergency Operation Centre 37 3.2.1 Communication Network 37 3.2.2 Police Wireless Set 38 3.2.3 Alert and Information System (SMS Software) 38 3.3 Early warning System:- 40 3.3.1 Rainfall Report 40 Prevention 3.4 Prevention 41 Mitigation Strategy 3.5 Mitigation Strategy 4 3.5.1 Structural Mitigation 4 3.5.1.1 Risk Assessment & Vulnerability Analysis 43 3.5.1.2 Hazard Assessment 44 3.5.1.3 Building Bye-laws & Codes 4. -

Format of Bio-Data in Respect of Persons Desirous of Inclusionin DPE Databank

- Format of Bio-data in respect of persons desirous of inclusionin DPE databank 1. Name and surname (in full):Anirban Mukhopadhaya 2. Director Identification Number (refer Note 1) : 07197450 3. Income Tax PAN: 4. Gender : Male 4. Nationality : Indian 5. Father's name and mother's name and Spouse's name (if married) : Late S.R. Mukerji, (father),Smt. Sipra Mukerji, (mother), Debasrita Mukhopadhaya, (spouse) 6. Date of Birth: 18June 1957 7. Present Position/Occupation Superannuated from the Indian Administrative Service on 30/ 06/2017 8. Full address (present and permanent) with PIN code, Phone number, Mobile Number, E-Mail address) : - Mobile No. 9414016355 Landiine. 0141 - 4087747. 9. Educational & Professional Qualification (Graduation onwards) S.No. Course Subjects University/Institut e Year of Passing 1 BA Hons. Natural Cambridge (U.K.) 1978 Sciences 2. MA Natural Cambridge (U.K.) 1982 Sciences 3. MA History Delhi 1980 4. MBA Finance Southern Cross 1996 Specialisation (Australia) 10 . Work Experience (Recent & Highlights) - Full Service History Sheet attached S.No. Organization/ Post Held Period (From To) Nature of Institute Work/ Area of Specialization 1 Rajasthan Chairman 06/05/2017 -30/06/2017 Judicial, Civil Services (superannuation) (Personnel) Appellate Tribunal, Jaipur 2 Rajasthan Chairman & 01/07/2016 - Urban Housing Housing 05/05/2017 Development & Board Commissioner Housing and Corporate Governance as Director in the Jaipur Metro Rail Corporation 3 Government Additional 20/09/2014 - Security, of Rajasthan Chief 01/07/2016 Administration, Secretary, Law, Finance & Home, Civil Corporate Defence,Home Governance as Guards, Jails, Director in the State Bureau Police Housing of Corporation Investigation and ex-officio Chief Vigilance Commissioner Rajas than 4 Government Principal 16/08/2010 - Personnel, of Rajasthan Secretary & 07/08/2014 Legal & later Constitutional, Additional University Chief administration, Secretary to Tribal the Governor Development of Rajasthan etc. -

Participant List

15th Round of MCTP Phase IV, 2021 (02-08-2021 to 27-08-2021) List of Participants Sl. No.Name & Address Gender Cadre Allotment Year 1 Dr. Sharat Chauhan, Male AGMUT 1994 Principal Secretary, Finance and Health, Government of Arunachal Pradesh, Block-02, 3rd Floor, Civil Secretariat, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh-791111 2 Swati Sharma, Female AGMUT 2003 Secretary, Government of NCT of Delhi, Delhi Secretariat, I P Estate, New Delhi- 110002 3 Ankur Garg, Male AGMUT 2003 Commissioner Trade and Taxes, Government of NCT of Delhi, 33-A, Shamnath Marg, New Delhi-110054 4 Shurbir Singh, Male AGMUT 2004 Secretary Finance and Chief Electoral Officer, Government of Pondicherry, Office of Secretary Finance, 3rd floor Chief Secretariat, Goubert Avenue, Pondicherry-605001 5 Garima Gupta, Female AGMUT 2004 Secretary, Government of NCT of Delhi, 6 by 8 Lancer Road, Opp. Vishwavidylaya Metro Station, Timarpur, Civil Lines, Delhi-110054 6 Niharika Rai, Female AGMUT 2005 Commissioner, Government of Arunachal Pradesh, Room No. 202, Block 2, Civil Secretariat, Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh-791111 7 Ashish Madhaorao More, Male AGMUT 2005 Additional Commissioner, North Delhi Municipal Corporation, Government of NCT of Delhi, Flat No. A-8, Delhi Government Residential Complex, Sector D-2, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110070 8 H. Lalengmawia, Male AGMUT 2005 Commissioner and Secretary, Power And Electricity Department And Sports, Government of Mizoram Room No. 116,117, Building No. 1, MINECO, KHATLA, Aizawl, Mizoram-796001 9 Kunal, Male AGMUT 2005 Chief Electoral Officer, Office of Chief Electoral Office, Government of Goa, Old IPHB Building, Altinho, Panaji, Goa-403001 10 Rupesh Kumar Thakur, Male AGMUT 2006 Director, Ministry of Labour, Shram Shakti Bhawan, Rafi Marg, New-Delhi-110001 11 Ashok Kumar, Male AGMUT 2006 Secretary, Government of Puducherry, No. -

To View/Download. Pdf/1.08 MB

• 9-117 II—taus 3(i)] Arta (NA (-171 : aMMTTIII 61 (xviii) "Pay Matrix" means the Matrix specified in the Schedule III with Levels of pay arranged in vertical cells as assigned to corresponding existing Pay Band and Grade Pay or scale; (xix) "Personal pay" means additional pay granted to a member of the Service — (a) to save him from a loss in his substantive pay in respect of a permanent post other than a tenure post due to a revision of pay or due to any reduction of such substantive pay otherwise than as a disciplinary measure; or (b) in exceptional circumstances, on other personal considerations; (xx) "promoted officer" means an officer appointed to the Indian Administrative Service by promotion from a State Civil Service in accordance with sub-rule (1) of rule 8 of the Indian Administrative Service (Recruitment) Rules, 1954; (xxi) "promotion" means appointment of a member of the Service to the next higher grade over the one in which he is serving at the relevant time; (xxii)"revised pay structure"in relation to any post specified in Schedule II means the Pay Matrix and the Levels specified therein corresponding to the existing Pay Band and Grade Pay or scale of the post unless a different revised Level is notified separately for that post; (xxiii)"revised emoluments" means the pay in the Level of a pay of a member of the Service in the revised pay structure or the basic pay in the Apex scale and the Cabinet Secretary's scale; (xxiv) "Schedule" means the Schedule appended to these rules; ( xxv) "Service" means the Indian Administrative Service; (xxvi) "State" means a State specified in the First Schedule to the Constitution and includes an Union territory; (xxvii) "State Cadre" and "Joint Cadre" have the meanings respectively assigned to them in the Indian Administrative Service (Cadre) Rules, 1954; (xxviii) "State Civil Service" shall have the meaning assigned to it in the Indian Administrative Service (Recruitment) Rules, 1954; and (xxix) "State Government concerned" in relation to a Joint Cadre means the Joint Cadre Authority. -

Indian Administration

mathematics HEALTH ENGINEERING DESIGN MEDIA management GEOGRAPHY EDUCA E MUSIC C PHYSICS law O ART L agriculture O BIOTECHNOLOGY G Y LANGU CHEMISTRY TION history AGE M E C H A N I C S psychology Basic of Indian Administration Subject:BASIC OF INDIAN ADMINISTRATION Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Historical Context Administrative System at the Advent of British Rule, British Administration: 1757-1858, Reforms in British Administration: 1858 to 1919, Administrative System under 1935 Act, Continuity and Change in Indian Administration: Post 1947 Central Administration Constitutional Framework, Central Secretariat: Organization and Functions, Prime Minister's Office and Cabinet Secretariat, Union Public Service Commission/Selection Commission, Planning Process, All India and Central Services State Administration Constitutional Profile of State Administration, State Secretariat: Organization and Functions, Patterns of Relationship Between the Secretariat and Directorates, State Services and Public Service Commission Field and Local Administration Field Administration, District Collector, Police Administration, Municipal Administration, Panchayati Raj and Local Government Citizen and Administration Socio-Cultural Factors and Administration, Redressal of Public Grievances, Administrative Tribunals Judicial Administration Emerging Issues Centre-State Administrative Relationship, Decentralization Debate Pressure Groups, Relationship Between Political and Permanent Executives, Pressure Groups, Generalists and Specialists, Administrative Reforms Suggested Readings: -

IAS CURRENT LIST As on 12.6.2018

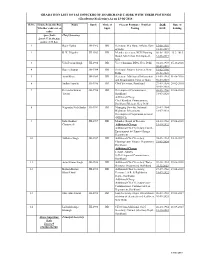

GRADATION LIST OF IAS OFFICERS OF JHARKHAND CADRE WITH THEIR POSTINGS (Gradewise/Scalewise) As on 13-06-2018 Sl.No. Grade/Scale (In Rs.) Name Batch Mode of Present Postings / Notified DOB Date of Whether cadre or ex- Appt. Posting DOR Joining cadre Apex Scale Chief Secretary Level-17 in the pay matric 2.25 Lac 1 Rajiv Gauba JH-1982 RR Secretary, M/o Home Affairs, Govt. 15-08-1959 of India 31-08-2019 2 B. K. Tripathi JH-1983 RR Member Secretary, NCR Planning 08-08-1959 25-3-2015 Board, M/o Urban Development, 31-08-2019 GOI 3 Udai Pratap Singh JH-1984 RR Vice Chairman, DDA, New Delhi 01-10-1958 05-10-2016 30-09-2018 4 Rajeev Kumar JH-1984 RR Secretary, Finance Services, New 19-02-1960 Delhi 28-02-2020 5 Amit Khare JH-1985 RR Secretary, Ministry of Information 14-09-1961 01-06-2018 and Broadcasting, Govt. of India 30-09-2021 6 Sudhir Tripathi JH-1985 RR Chief Secretary, Jharkhand 27-09-1958 28-02-2018 30-09-2018 7 Devendra Kumar JH-1986 RR Development Commissioner, 26-03-1960 07-06-2018 Tiwari Jharkhand 31-03-2020 Additional Charge Chief Resident Commissioner, Jharkhand Bhawan, New Delhi 8 Nagendra Nath Sinha JH-1987 RR Managing Director, National 29-07-1964 Highways Infrastructure 31-07-2024 Development Corporation Limited (NHIDCL) 9 Indu Shekhar JH-1987 RR Member, Board of Revenue 24-10-1962 07-06-2018 Chaturvedi Additional Charge 31-10-2022 Additional Chief Secretary, Forest, Environment & Climate Change Department 10 Sukhdeo Singh JH-1987 RR Additional Chief Secretary, 05-03-1964 04-12-2017 Planning-cum- Finance Department 31-03-2024 Jharkhand Additional Charge 1) M.D., GRDA 2) Development Commissioner, Jharkhand 11 Arun Kumar Singh JH-1988 RR Additional Chief Secretary, Water 07-12-1963 07-06-2018 Resource Department, Jharkhand 31.12.2023 12 Kailash Kumar JH-1988 RR Additional Chief Secretary, 27-07-1962 19-04-2018 Khandelwal Personnel, A.R. -

Introduction

Community Based Resource Management ... 1 INTRODUCTION India’s forest management policies have been the centre of intense debate on environment and development for over last three and a half decades. Concern for the state of forests arises from the increasing awareness that forests are essential for sustainable development of not only the population living in and around forests but also as repository of nation’s valuable natural resources including genetic diversity. It is argued that the State has usurped the rights of local communities over a period of time leading to alienation of local population from the management of forests. On the other hand, forests under State management have suffered serious depletion due to relentless pressure from ever increasing demand from trade and industry and the tendency of the forest department to look upon forests as revenue earning resources (Khanna & Sama, 2001). The manifest failure of State and market mechanisms to promote sustainable and equitable natural resources management in developing societies has stimulated a search for community based alternatives (Agrawal & Gipson, 1999). It is argued that community based natural resource management (CBNRM) offers the best prospect for meeting conservation objectives while improving the condition of marginalised forest communities who are denied the fundamental right to substantive participation in decisions that impact on their well-being and livelihood. The basic assumption of CBNRM is that people who live close to a resource and whose livelihoods directly depend upon it have more interest in sustainable use and management than State authorities and distant corporations (Li, 2002). Our experience with social forestry and eco-development programmes proves the point. -

HQ/DDMA Orders/Misc Matters/21Li38 Dated:12.06.2021 ORDER

GOVERNMENT OF NCT OF DELHI DELHI DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY No.F. 1(571)/DDMA (HQ/DDMA Orders/Misc Matters/21Li38 Dated:12.06.2021 ORDER In exercise of powers conferred under Section 22 of the Disaster Management Act, 2005, the in undersigned, his capacity as Chairperson, State Executive Committee, DDMA, GNCTD hereby directs that the restrictions imposed by DDMA vide Order No. 411 dated 06.05.2021 read with Order No. 424 dated 19.05.2021 with regard to persons coming from the States of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana to NCT of Delhi through Buses Cars / Trucks or any other mode of transportation in the territoryAirlines/ of NCT ofTrains Delhi, stands withdrawn with immediate effect. 2. All District Magistrates, their counterpart District DCPs and ali authorities concerned shall ensure strict compliance of this order and shall adequately inform and sensitize the field functionaries about these instructions for strict compliance, in letter & spirit. (Vijay Dev) Chief Secretary, Delhi Copy for compliance to: State Nodal Officers for COVID-19 (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana) 2. Commissioner of Police, Delhi Chairman, New Delhi Municipal Council 4 Pr. Secretary (H&FW), GNCTD 5 Pr. Secretary (Revenue)-cum-Divisional Commissioner, GNCTD Pr. Secretary(Transport), GNCTD 7. Commissioner (South DMC/East DMC/North DMC) 8. The Resident Commissioners of State Bhawan of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana 9 Secretary (1&P) for wide publicity in NCT of Delhi 10 CEO, Delhi Cantonment Board 11. All District Magistrates of Delhi 12 All District DCPs of Delhi Copy for kind information to: 1. Secretary to Hon'ble Lt. Governor, Delhi. -

Uttarakhand Char Dham Devasthanam Management Board

iD-q qudll-o7 crfif,$'r qleqr-{o\o /'Sooto T$oSol.rqo / za / zon-zozo ffiwr€. sfl{rquE st3D.r{ Hl-{T qfi-Irqff, - frqrfr qRfu€ srq-1, q-s (o) (uowwu-s sftft{q) tg{r(q. Eerqn. rs q;rcft, zozo {o frc zs, 1941 {tf wtrkT. ! g-t{I€TU-g YII-TI.T @ rrwl 1771Lxvt (s)/zozo / a{t) / zots .ru fuir{l. 6qefr, 2o2o eferqa-+r fdFdq gOqrcog "qrgd 261 s'Et]lq" $ Gr-J-d-{ zoo d ettrq qo {-\'qqIf, i ftqfq glrlT gnt qRfl 'gGNr€lrrg qn ffi tq{ery qq-arq fr*{rfi. 2o1e' st ffi6 ra q{, u1-r-q_fr, zozo qt} 3r-iqfr qqrq qt1 eilq m B-f,{fclu-s 6T 3Tfuftqq €wr: oo zozo d sq ti sd-qnmor d qqflQf gs uB-qqqT am e-oTRT-d ftrqr rntaT i t qqq) grnfslo-g srcIrqTq-ur q-qe. 15 q{-dft. 2020 {o (qtq zs, 1941 RliF vf,(I€iss il{ qIq e-fieil-{{ ssaFT sftFr{q, 2o1e (s*rs"s 3fqfr-'qq sst oo, o{ zozo) 3|wrq \rtr srukftt 1. ---R-- 2. ql{flrffq 3ilq qrFilqi ti *d o.r.raq. flrf cn"r i g , qn uq eimafiq1 Er€ 16q q-d-di qqFI 3ilEn{I s-qm{fq qftft irr r-d;I i 10" 4a I i. 12. 3lung qN er*q o1 frgfrn qffi rni o,'ffitil I I I sfldr€ru-s qglErrtuT qcrc. 1s q-ffS. 2020 {0 (du zs, 1941 qFD'sqO 3ilqrq gfg ffiffiffircfiffiffif frffiCIkryam €ffiffiT 6: qR qrq tgwrm irr rnTr..rt=t eilT gew SiHIEI HTd qFfr, gqrft, vrqa {srR afr ftgRd, rrscittr sflT Fqtrqr-dT 1V EdEII q.I;TI SfEn-q 9fi-6 ftril, qR qrq frft sln qqe qq ffi o-r silgqqur , qR qlri i-4U 6-l I3q, qu[e, 6-r T-qrffiI attfr q|"q qflnRr ?bT q{eilwT gKr sTrq qqfi 36- 6] 3rSqeTuI i g|tr€Iu-g sftIIEIItuT qqe. -

Report of the Expert Committee on Land Leasing

REPORT OF THE EXPERT COMMITTEE ON LAND LEASING NITI AAYOG Govt. of India New Delhi March 31, 2016 The views expressed in this report are of the Expert Committee and not of NITI Aayog or Govt of India. 1 Preface This report is in pursuance of the communication of the NITI Aayog, Govt. of India, vide order No. Q11022/12/2015-Agri dated September 07, 2015 to constitute an Expert Committee, for preparing a Model Agricultural Land Leasing Act, based on critical review of the existing agricultural tenancy laws of States and keeping in view the need to legalize land leasing. The composition and terms of reference of the Committee are shown in Annexure- I. The Committee had held several meetings and consultations with various stakeholders, the list of which is given in Annexure – II. I take this opportunity to convey my sincere thanks and appreciation to all the members of the Expert Committee for their contributions in finalizing the report. The help and co-operation of Dr. J.P. Mishra, Member-Secretary of the Committee, Shri. Y. S. Malik, Additional Secretary, Niti Aayog and other officers of the Agriculture Division, NITI Aayog are gratefully acknowledged. Besides, valuable contributions of Special invitees to the Expert Committee meetings, such as Mr. Sunil Kumar, Nalsar University of Law, Hyderabad Dr. Vijendra Kumar, Vice-Chancellor, National Law University, Guwahati and Prof. R.S. Deshpande, Director, Institute of Economic & Social Change , Bangalore, and Mr. Paras Kuhad, eminent land lawyer are acknowledged. Finally, I thank Ms. Jaya Nair and Mr. Gitesh Sinha of CSD for their valuable assistance. -

Template Service Profile for Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

Template Service Profile for Indian Administrative Service (IAS) Overview Indian Administrative Service (IAS) the premier service of Government of India was constituted in 1946. Prior to that Indian Imperial Service (1893-1946) was in force. As on 1.1.2013, sanctioned strength of IAS was 6217 comprising of 4313 posts to the filled by direct recruits and 1904 posts to be filled by promotion /appointment of State Civil Services officers/ Non-State Civil Service officers. The civil services have been a hallmark of governance in India. The Constitution provides that without depriving the States of their right to form their own Civil Services there shall be an All India service recruited on an All- India basis with common qualifications, with uniform scale of pay and the members of which alone could be appointed to these strategic posts throughout the Union." No wonder that Sardar Vallabhai Patel, one of the eminent leaders of the freedom struggle referred to the ICS as the steel frame of the country. The civil services, therefore, represents the essential spirit of our nation - unity in diversity. Recruitment At present there are three modes of recruitment to IAS viz (i) Through Civil Services Examination conducted by UPSC every year; (ii) Through promotion of State Civil Service officers to IAS; and (iii) Through selection of non - State Civil Service officers. Roughly 66(1/3%) posts are meant for Direct Recruitment and 33 (1/3%) posts are meant for promotion quota. Training Both Direct Recruit as well as promotee IAS officers are imparted probationary training at Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration (LBSNAA). -

Uttarkashi.Pdf

on 3 in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley rd A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster on 3rd August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand Surya Parkash World Centre of Excellence on Landslide Disaster Reduction ISBN 978-93-82571-10-0 National Institute of Disaster Management World Centre of Excellence on Landslide Disaster Reduction Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India National Institute of Disaster Management 5 B, I.P. Estate, Ring Road, New Delhi – 110 002 9 7 8 9 3 8 2 5 7 1 1 0 0 Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India www.nidm.gov.in 5 B, I.P. Estate, Ring Road, New Delhi – 110 002 www.nidm.gov.in A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster on 3rd August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand by Surya Parkash, Ph.D. World Centre of Excellence on Landslide Disaster Reduction National Institute of Disaster Management Ministry of Home Affairs, Govt. of India 5 B, I.P. Estate, Ring Road, New Delhi – 110 002 www.nidm.gov.in A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster on 3rd August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand Report Prepared and Submitted by Dr. Surya Parkash to NIDM, New Delhi during August 2012 ISBN 978-93-82571-10-0 © NIDM, New Delhi Edition : First, 2015 Published by National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM), Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi - 110 002, India Citation Parkash Surya (2015). A Study on Flash Floods and Landslides Disaster on 3rd August 2012 along Bhagirathi Valley in Uttarkashi District, Uttarakhand, National Institute of Disaster Management, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, New Delhi - 110 002, 230 Pages Disclaimer This document may be freely reviewed, reproduced or translated, in part or whole, purely on non-profit basis for humanitarian, social and environmental well-being, We welcome receiving information and suggestions on its adaptation or use in actual training situations.