Substance Abuse Among Older Adults: an Invisible Epidemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 697 CG 021 192 AUTHOR Gougelet, Robert M.; Nelson, E. Don TITLE Alcohol and Other Chemicals. Adolescent A

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 300 697 CG 021 192 AUTHOR Gougelet, Robert M.; Nelson, E. Don TITLE Alcohol and Other Chemicals. Adolescent Alcoholism: Recognizing, Intervening, and Treating Series No. 6. INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Dept. of Family Medicine. SPONS AGENCY Health Resources and Services Administration (DHHS/PHS), Rockville, MD. Bureau of Health Professions. PUB DATE 87 CONTRACT 240-83-0094 NOTE 30p.; For other guides in this series, see CG 021 187-193. AVAILABLE FROMDepartment of Family Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210 ($5.00 each, set of seven, $25.00; audiocassette of series, $15.00; set of four videotapes keyed to guides, $165.00 half-inch tape, $225.00 three-quarter inch tape; all orders prepaid). PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Materials (For Learner) (051) -- Reports - General (140) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Plstage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescents; *Alcoholism; *Clinical Diagnosis; *Drug Use; *Family Problems; Physician Patient Relationship; *Physicians; Substance Abuse; Units of Study ABSTRACT This document is one of seven publications contained in a series of materials for physicians on recognizing, intervening with, and treating adolescent alcoholism. The materials in this unit of study are designed to help the physician know the different classes of drugs, recognize common presenting symptoms of drug overdose, and place use and abuse in context. To do this, drug characteristics and pathophysiological and psychological effects of drugs are examined as they relate to administration, -

Practitioners Guide for Medications in Alcohol and Drug Dependence

PRACTITIONERS GUIDE FOR MEDICATIONS IN ALCOHOL AND DRUG DEPENDENCE INTRODUCTION It is likely the majority of chemically dependent persons will probably need medications (including both prescriptions and over-the counter) at some point in their recovery. At any time, such medications should only be taken as prescribed by their primary physician in conjunction with their addiction specialist. This Guide is intended to serve as a resource for the recovering chemically dependent person and the medical professional prescribing treatment. It is not meant to be used exclusively or as the sole means for providing advice regarding medications. Indeed, this Guide would be best utilized in conjunction with other concurrent reference materials. Decisions about particular prescription medication(s) should be tailored to the needs of the individual patient under the direction of a health professional. This Guide is not intended to be exhaustive, nor an endorsement of any particular brand name medication. Rather it is intended to provide relevant pharmacological information to the recovering person and health care providers treating those in recovery. GUARDING AGAINST ADDICTION Recovering alcoholics and addicts must be constantly alert to the possibility of triggering a relapse of their disease through the intake of drugs or alcohol. Just as a diabetic needs to be cautious about the intake of sugar, the recovering alcoholic must be sensitive to drugs and the recovering addict must be sensitive to alcohol, and both must be sensitive to other mood-altering drugs, including prescribed and over-the-counter preparations. This Guide is designed to serve as a resource when making decisions regarding what medication(s) to take, as well as a reference tool for those who prescribe medication for persons in recovery. -

Barbiturates

URINE DRUG TEST INFORMATION SHEET BARBITURATES Classification: Central nervous system depressants insomnia, anxiety or tension due to their very high (CNS Depressants) risk of physical dependence and fatal overdose. Due to the structural nature of barbiturates, the duration Background: Barbiturates are a group of drugs of action does not always correlate well with the that act as central nervous system depressants. biological half-life. Opiates, benzodiazepines and alcohol are also CNS depressants, and like their use, the effect seems to Physiological Effects: Lowered blood pressure, the user as an overall sense of calm. Barbiturates respiratory depression, fatigue, fever, impaired were introduced in 1903, dominating the sedative- coordination, nystagmus, slurred speech and ataxia hypnotic market for the first half of the twentieth century. Unfortunately, because barbiturates have Psychological Effects: Drowsiness, dizziness, unusual a relatively low therapeutic-to-toxic index and excitement, irritability, poor concentration, sedation, substantial potential for abuse, they quickly became confusion, impaired judgment, addiction, euphoria, a major health problem. Barbiturates are commonly decreased anxiety and a loss of inhibition abused for their sedative properties and widespread Toxicity: Barbiturates are especially more availability. The introduction of benzodiazepines in dangerous when abused with alcohol, opiates and the 1960s quickly supplanted the barbiturates due benzodiazepines because they act on the same to their higher safety -

Drugs of Abuse Screens 5,6,9 – Detection Limits

Drugs of Abuse Screens 5,6,9 – Detection limits Amphetamines low detection limit Benzodiazepines low detection limit d-Amphetamine 1286 ng/mL Alprazolam 65 ng/mL d,I-Amphetamine 2139 ng/mL 7-aminoclonazepam 2600 ng/mL d-Methamphetamine 1000 ng/mL 7-aminoflunitrazepam 590 ng/mL d,I-Methamphetamine 1564 ng/mL Bromazepam 630 ng/mL I-Amphetamine 10407 ng/mL Chlordiazepoxide 3300 ng/mL I-Methamphetamine 2273 ng/mL Clobazam 260 ng/mL Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) 3537 ng/mL Clonazepam 580 ng/mL Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) 20538 ng/mL Clotiazepam 380 ng/mL Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA) 18230 ng/mL Demoxepam 1600 ng/mL 4-Chloramphetamine 10 µg/mL N-Desalkylflurazepam 130 ng/mL Benzphetamine 1 µg/mL N-Desmethyldiazepam 110 ng/mL Bupropion 1038 µg/mL Diazepam 70 ng/mL Chloroquine 3741 µg/mL Estazolam 90 ng/mL I-Ephedrine 2242 µg/mL Flunitrazepam 140 ng/mL Fenfluramine 105 µg/mL Flurazepam 190 ng/mL Mephentermine 30 µg/mL Halazepam 110 ng/mL Methoxypenamine 331 µg/mL α-Hydroxyalprazolam 100 ng/mL Nor-pseudoephedrine 188 µg/mL 1-N-Hydroxyethylflurazepam 150 ng/mL Phenmetrazine 9 µg/mL α-Hydroxytriazolam 130 ng/mL Phentermine 21 µg/mL Ketazolam 100 ng/mL Phenylpropanolamine (PPA) 133 µg/mL Lorazepam 600 ng/mL Propranolol 386 µg/mL Lormetazepam 200 ng/mL Pseudoephedrine 5889 µg/mL Medazepam 150 ng/mL Quinacrine 8293 µg/mL Midazolam 130 ng/mL Tranylcypromine 126 µg/mL Nitrazepam 320 ng/mL Tyramine 503 µg/mL Norchlordiazepoxide 2600 ng/mL Barbiturates low detection limit Oxazepam 250 ng/mL Allobarbital 345 ng/mL Prazepam 90 ng/mL Alphenal -

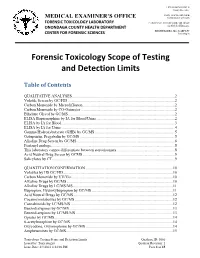

Forensic Toxicology Scope of Testing and Detection Limits

J. RYAN MCMAHON II County Executive INDU GUPTA, MD, MPH MEDICAL EXAMINER’S OFFICE Commissioner of Health FORENSIC TOXICOLOGY LABORATORY CAROLYN H. REVERCOMB, MD, DABP ONONDAGA COUNTY HEALTH DEPARTMENT Chief Medical Examiner KRISTIE BARBA, MS, D-ABFT-FT CENTER FOR FORENSIC SCIENCES Toxicologist Forensic Toxicology Scope of Testing and Detection Limits Table of Contents QUALITATIVE ANALYSES.........................................................................................................2 Volatile Screen by GC/FID .............................................................................................................2 Carbon Monoxide by Microdiffusion..............................................................................................2 Carbon Monoxide by CO-Oximeter ................................................................................................2 Ethylene Glycol by GC/MS.............................................................................................................2 ELISA Buprenorphine by IA for Blood/Urine ................................................................................2 ELISA by IA for Blood ...................................................................................................................3 ELISA by IA for Urine....................................................................................................................4 Gamma Hydroxybutyrate (GHB) by GC/MS..................................................................................5 Gabapentin, -

Laws 2021, LB236, § 4

LB236 LB236 2021 2021 LEGISLATIVE BILL 236 Approved by the Governor May 26, 2021 Introduced by Brewer, 43; Clements, 2; Erdman, 47; Slama, 1; Lindstrom, 18; Murman, 38; Halloran, 33; Hansen, B., 16; McDonnell, 5; Briese, 41; Lowe, 37; Groene, 42; Sanders, 45; Bostelman, 23; Albrecht, 17; Dorn, 30; Linehan, 39; Friesen, 34; Aguilar, 35; Gragert, 40; Kolterman, 24; Williams, 36; Brandt, 32. A BILL FOR AN ACT relating to law; to amend sections 28-1202 and 69-2436, Reissue Revised Statutes of Nebraska, and sections 28-401 and 28-405, Revised Statutes Cumulative Supplement, 2020; to redefine terms, change drug schedules, and adopt federal drug provisions under the Uniform Controlled Substances Act; to provide an exception to the offense of carrying a concealed weapon as prescribed; to define a term; to change provisions relating to renewal of a permit to carry a concealed handgun; to provide a duty for the Nebraska State Patrol; to eliminate an obsolete provision; to harmonize provisions; and to repeal the original sections. Be it enacted by the people of the State of Nebraska, Section 1. Section 28-401, Revised Statutes Cumulative Supplement, 2020, is amended to read: 28-401 As used in the Uniform Controlled Substances Act, unless the context otherwise requires: (1) Administer means to directly apply a controlled substance by injection, inhalation, ingestion, or any other means to the body of a patient or research subject; (2) Agent means an authorized person who acts on behalf of or at the direction of another person but does not include a common or contract carrier, public warehouse keeper, or employee of a carrier or warehouse keeper; (3) Administration means the Drug Enforcement Administration of the United States Department of Justice; (4) Controlled substance means a drug, biological, substance, or immediate precursor in Schedules I through V of section 28-405. -

201 PART 329—HABIT-FORMING DRUGS Subpart A—Derivatives

Food and Drug Administration, HHS § 329.1 section 502(e) of the Federal Food, PART 329ÐHABIT-FORMING DRUGS Drug, and Cosmetic Act. (d) The statement expressing the Subpart AÐDerivatives Designated as amount (percentage) of alcohol present Habit Forming in the product shall be in a size reason- ably related to the most prominent Sec. printed matter on the panel or label on 329.1 Habit-forming drugs which are chem- which it appears, and shall be in lines ical derivatives of substances specified in generally parallel to the base on which section 502(d) of the Federal Food, Drug, the package rests as it is designed to be and Cosmetic Act. displayed. (e) For a product to state in its label- Subpart BÐLabeling ing that it is ``alcohol free,'' it must 329.10 Labeling requirements for habit- contain no alcohol (0 percent). forming drugs. (f) For any OTC drug product in- tended for oral ingestion containing Subpart CÐExemptions over 5 percent alcohol and labeled for use by adults and children 12 years of 329.20 Exemption of certain habit-forming age and over, the labeling shall contain drugs from prescription requirements. the following statement in the direc- AUTHORITY: 21 U.S.C. 352, 353, 355, 371. tions section: ``Consult a physician for use in children under 12 years of age.'' SOURCE: 39 FR 11736, Mar. 29, 1974, unless (g) For any OTC drug product in- otherwise noted. tended for oral ingestion containing over 0.5 percent alcohol and labeled for Subpart AÐDerivatives use by children ages 6 to under 12 years Designated as Habit Forming of age, the labeling shall contain the following statement in the directions § 329.1 Habit-forming drugs which are section: ``Consult a physician for use in chemical derivatives of substances children under 6 years of age.'' specified in section 502(d) of the (h) When the direction regarding age Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic in paragraph (e) or (f) of this section Act. -

Pharmaceuticals (Monocomponent Products) ………………………..………… 31 Pharmaceuticals (Combination and Group Products) ………………….……

DESA The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global and policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environmental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Note Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of the capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. Applications for the right to reproduce this work or parts thereof are welcomed and should be sent to the Secretary, United Nations Publications Board, United Nations Headquarters, New York, NY 10017, United States of America. Governments and governmental institutions may reproduce this work or parts thereof without permission, but are requested to inform the United Nations of such reproduction. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Copyright @ United Nations, 2005 All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction …………………………………………………………..……..……..….. 4 Alphabetical Listing of products ……..………………………………..….….…..….... 8 Classified Listing of products ………………………………………………………… 20 List of codes for countries, territories and areas ………………………...…….……… 30 PART I. REGULATORY INFORMATION Pharmaceuticals (monocomponent products) ………………………..………… 31 Pharmaceuticals (combination and group products) ………………….……........ -

483 Administrative Records, Texas Department of Criminal Justice

Consistent with the terms of the Court’s May 22, 2017 scheduling order, the record has been redacted for all information that plaintiff, Texas Department of Criminal Justice (Texas), has identified as confidential. In addition, Defendants have also redacted information that the drug’s supplier and broker have separately advised the agency they consider confidential and private, as well as information the agency itself generally treats as confidential. This information has been redacted pending final FDA’s review of confidentiality claims, and our filing of the record with these redactions does not necessarily reflect our agreement with all of the claims of confidentiality Defendants have received. Defendants explicitly reserve the right to make an independent determination regarding the proper scope of redactions at a later time. Should we identify any of Texas’s redactions that are over-broad or otherwise improper, we will work with Texas’s counsel to revise the redactions in the record. Exhibit 14 FDA 095 Case 1:11-cv-00289-RJL Document 13-3 Filed 04/20/11 Page 1 of 74 CERTJFICATE Pursuant to the provisions ofRule 44 ofthe Federal Rules ofCivil Procedure, I hereby certifY that John Verbeten, Director ofthe Operations and Policy Branch, Division of Import Operations and Policy, Office ofRegional Operations, Office ofRegulatory Affairs, United States Food and Drug Administration, whose declaration is attached, has custody ofofficial records ofthe United States Food and Drug Administration. In witness whereof, I have, pursuant to the provision ofTitle 42, United States Code, Section 3505, and FDA StaffManual Guide 1410.23, hereto set my hand and caused the seal ofthe Department ofHealth and Human Services to be affixed th.is ~oi{. -

Drug Screen Listing

DRUG SCREEN LISTING The following are detected by a general urine drug screen. Abacavir Acebutolol Acetaminophen Acetohexamide Acyclovir Alprazolam Alprazolam metabolite (alpha-Hydroxyalprazolam) Alprenolol Amantadine Ambroxol Amiloride Amiodarone Amitriptyline Amlodipine Amobarbital as BAR Amoxapine Amphetamine Aprobarbital as BAR Aripiprazole Aripiprazole metabolite (dehydro-aripiprazole) Atenolol Atomoxetine Atorvastatin Atropine Baclofen Barbital as BAR Bendiocarb Benzocaine Benztropine Betaxolol Bisoprolol Bromazepam Bromocriptine Brompheniramine Bupivacaine Buprenorphine Buprenorphine metabolite (norbuprenorphine) Bupropion Buspirone Butabarbital as BAR Butalbital as BAR BZP (1-benzylpiperazine) Caffeine Captopril Carbamazepine Carbamazepine metabolite (10,11-dihydro-10,11- Page 1 of 13 dihydroxycarbamazepine) Carbamazepine metabolite (carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide) Carisoprodol Carvedilol Cathinone Cetirizine Chlordiazepoxide Chlordiazepoxide metabolite (norchlordiazepoxide) Chloroquine Chlorpheniramine Chlorpromazine Chlorpropamide Chlorprothixene Cilazapril Cimetidine Citalopram Citalopram metabolite (desmethylcitalopram) Clenbuterol Clobazam Clobazam metabolite (desmethylclobazam) Clomipramine Clomipramine metabolite (desmethylclomipramine) Clonazepam Clonazepam metabolite (7-Aminoclonazepam) Clonidine Clozapine Clozapine metabolite (clozapine-N-oxide) Clozapine metabolite (norclozapine) Cocaine Cocaine metabolite (benzoylecgonine) Cocaine metabolite (cocaethylene) Cocaine metabolite (ecgoninemethylester) Cocaine metabolite (ethylecgonine) -

Sedative Hypnotics Leon Gussow and Andrea Carlson

CHAPTER 165 Sedative Hypnotics Leon Gussow and Andrea Carlson BARBITURATES three times therapeutic, the neurogenic, chemical, and hypoxic Perspective respiratory drives are progressively suppressed. Because airway reflexes are not inhibited until general anesthesia is achieved, Barbiturates are discussed in do-it-yourself suicide manuals and laryngospasm can occur at low doses. were implicated in the high-profile deaths of Marilyn Monroe, Therapeutic oral doses of barbiturates produce only mild Jimi Hendrix, Abbie Hoffman, and Margaux Hemingway as well decreases in pulse and blood pressure, similar to sleep. With toxic as in the mass suicide of 39 members of the Heaven’s Gate cult in doses, more significant hypotension occurs from direct depression 1997. Although barbiturates are still useful for seizure disorders, of the myocardium along with pooling of blood in a dilated they rarely are prescribed as sedatives, with the availability of safer venous system. Peripheral vascular resistance is usually normal or alternatives, such as benzodiazepines. Mortality from barbiturate increased, but barbiturates interfere with autonomic reflexes, poisoning declined from approximately 1500 deaths per year in which then do not adequately compensate for the myocardial the 1950s to only two fatalities in 2009.1 depression and decreased venous return. Barbiturates can precipi- Barbiturates are addictive, producing physical dependence and tate severe hypotension in patients whose compensatory reflexes a withdrawal syndrome that can be life-threatening. Whereas tol- are already maximally stimulated, such as those with heart failure erance to the mood-altering effects of barbiturates develops or hypovolemic shock. Barbiturates also decrease cerebral blood rapidly with repeated use, tolerance to the lethal effects develops flow and intracerebral pressure. -

Drug of Abuse Cut Off Values

Swedish Laboratory Services – Chemistry Department Drugs of Abuse Concentrations of Compounds that Produce a Result Approximately Equivalent to the Cut-off Value. Drug Category: Amphetamines Compound/Drug Cut-off Unit: ng/mL d-amphetamine 1000 d,l-methamphetamine 1500 d,l-amphetamine 1961 l-methamphetamine 1798 l-amphetamine 8651 MDA 3794 MDMA 13037 MDEA 11192 Unit: μg/mL 4-chloramphetamine 8.2 benzphetamine* 1.3 bupropion 814 chloroquine 3233 l-ephedrine 2240 fenfluramine 75 mephentermine 22.2 methoxyphenamine 231 nor-pseudoephedrine 142 phenmetrazine 6.9 phentermine 16.8 phenylpropanolamine 2000 propranolol 306 d,l-pseudoephedrine 4340 quinacrine 5696 tranylcypromine 85 tyramine 390 * Benzphetamine metabolized to amphetamine and methamphetamine. CHEM.09.909 Advia 1650 Drug of Abuse Cut-off Values Swedish Laboratory Services – Chemistry Department Drug Category: Benzodiazepine Compound/Drug Cut-off Unit: ng/mL alprazolam 65 7-aminoclonazepam 2600 7-aminoflunitrazepam 590 bromazepam 630 chlordiazepoxide 3300 clobazam 260 clonazepam 580 clorazepate * clotiazepam 380 demoxepam 1600 N-desalkylflurazepam 130 N-desmethyldiazepam 110 diazepam 70 estazolam 90 flunitrazepam 140 flurazepam 190 halazepam 110 α-hydroxyalprazolam 100 α-hydroxyalprazolam glucuronide† 110 1-N-hydroxyethlylflurazepam 150 α-hydroxytriazolam 130 ketazolam 100 lorazepam 600 lorazepam glucuronide† >20,000 medazepam 150 midazolam 130 nitrazepam 320 norchlordiazepoxide 2600 oxazepam 250 oxazepam glucuronide† >50,000 prazepam 90 temazepam 140 temazepam glucuronide† 6900 tetrazepam 70 triazolam 130 * Clorazepate degrades rapidly in stomach acid to nordiazepam. Nordiazepam hydroxylates to oxazepam. † The glucuronide metabolite of α-hydroxyalprazolam cross-reacts with this method. Other glucuronide metabolites, such as lorazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam cross-react to a limited extent. The cross-reactivity of other glucuronide metabolites with this method is not known.