Property,Bundle of Rights,Exclusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water

Florida State University Law Review Volume 3 Issue 4 Article 1 Fall 1975 The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water Glenn J. MacGrady Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Admiralty Commons, and the Water Law Commons Recommended Citation Glenn J. MacGrady, The Navigability Concept in the Civil and Common Law: Historical Development, Current Importance, and Some Doctrines That Don't Hold Water, 3 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 511 (1975) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol3/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 3 FALL 1975 NUMBER 4 THE NAVIGABILITY CONCEPT IN THE CIVIL AND COMMON LAW: HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT, CURRENT IMPORTANCE, AND SOME DOCTRINES THAT DON'T HOLD WATER GLENN J. MACGRADY TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ---------------------------- . ...... ..... ......... 513 II. ROMAN LAW AND THE CIVIL LAW . ........... 515 A. Pre-Roman Legal Conceptions 515 B. Roman Law . .... .. ... 517 1. Rivers ------------------- 519 a. "Public" v. "Private" Rivers --- 519 b. Ownership of a River and Its Submerged Bed..--- 522 c. N avigable R ivers ..........................................- 528 2. Ownership of the Foreshore 530 C. Civil Law Countries: Spain and France--------- ------------- 534 1. Spanish Law----------- 536 2. French Law ----------------------------------------------------------------542 III. ENGLISH COMMON LAw ANTECEDENTS OF AMERICAN DOCTRINE -- --------------- 545 A. -

The Law of Property

THE LAW OF PROPERTY SUPPLEMENTAL READINGS Class 14 Professor Robert T. Farley, JD/LLM PROPERTY KEYED TO DUKEMINIER/KRIER/ALEXANDER/SCHILL SIXTH EDITION Calvin Massey Professor of Law, University of California, Hastings College of the Law The Emanuel Lo,w Outlines Series /\SPEN PUBLISHERS 76 Ninth Avenue, New York, NY 10011 http://lawschool.aspenpublishers.com 29 CHAPTER 2 FREEHOLD ESTATES ChapterScope ------------------- This chapter examines the freehold estates - the various ways in which people can own land. Here are the most important points in this chapter. ■ The various freehold estates are contemporary adaptations of medieval ideas about land owner ship. Past notions, even when no longer relevant, persist but ought not do so. ■ Estates are rights to present possession of land. An estate in land is a legal construct, something apart fromthe land itself. Estates are abstract, figments of our legal imagination; land is real and tangible. An estate can, and does, travel from person to person, or change its nature or duration, while the landjust sits there, spinning calmly through space. ■ The fee simple absolute is the most important estate. The feesimple absolute is what we normally think of when we think of ownership. A fee simple absolute is capable of enduringforever though, obviously, no single owner of it will last so long. ■ Other estates endure for a lesser time than forever; they are either capable of expiring sooner or will definitely do so. ■ The life estate is a right to possession forthe life of some living person, usually (but not always) the owner of the life estate. It is sure to expire because none of us lives forever. -

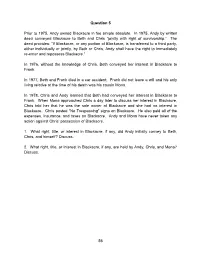

Question 5 Prior to 1975, Andy Owned Blackacre in Fee Simple Absolute. In

Question 5 Prior to 1975, Andy owned Blackacre in fee simple absolute. In 1975, Andy by written deed conveyed Blackacre to Beth and Chris “jointly with right of survivorship.” The deed provides: “If Blackacre, or any portion of Blackacre, is transferred to a third party, either individually or jointly, by Beth or Chris, Andy shall have the right to immediately re-enter and repossess Blackacre.” In 1976, without the knowledge of Chris, Beth conveyed her interest in Blackacre to Frank. In 1977, Beth and Frank died in a car accident. Frank did not leave a will and his only living relative at the time of his death was his cousin Mona. In 1978, Chris and Andy learned that Beth had conveyed her interest in Blackacre to Frank. When Mona approached Chris a day later to discuss her interest in Blackacre, Chris told her that he was the sole owner of Blackacre and she had no interest in Blackacre. Chris posted “No Trespassing” signs on Blackacre. He also paid all of the expenses, insurance, and taxes on Blackacre. Andy and Mona have never taken any action against Chris’ possession of Blackacre. 1. What right, title, or interest in Blackacre, if any, did Andy initially convey to Beth, Chris, and himself? Discuss. 2. What right, title, or interest in Blackacre, if any, are held by Andy, Chris, and Mona? Discuss. 56 Answer A to Question 5 1. WHAT RIGHT, TITLE OR INTEREST IN BLACKACRE DID ANDY INITIALLY CONVEY TO BETH, CHRIS, AND HIMSELF? Andy owned Blackacre in fee simple absolute, which indicates absolute ownership and means he had the full right to convey Blackacre. -

CONTRACTS MID-TERM EXAMINATION Santa Barbara/Ventura Colleges of Law Instructor: Craig Smith Fall 2013

CONTRACTS MID-TERM EXAMINATION Santa Barbara/Ventura Colleges of Law Instructor: Craig Smith Fall 2013 QUESTION 1 Moe, the owner of Blackacre, a single-family home, told Curly that he wanted to sell Blackacre for $300,000. Curly said to Moe that he would try to find a purchaser if Moe would agree to pay him a commission of 6%, and Moe orally agreed. Curly is not a licensed real estate broker. Thereafter, without Curly’s knowledge, Moe and Larry entered into negotiations for the sale of Blackacre. Larry faxed to Moe a signed letter stating that he offered to buy Blackacre for $250,000 in cash to be paid at the closing to take place in 90 days. The letter described Blackacre by street address and dimensions. Moe responded by mailing a signed letter to Larry stating that he was refusing Larry’s offer but would agree to sell Blackacre to him for $275,000 on the same terms. Larry immediately responded by mailing a signed letter to Moe stating that he agreed to the higher price. Before Moe received that letter from Larry, Curly presented Moe with a proposed contract for the sale of Blackacre to another prospective buyer for $300,000. Moe immediately sent a letter by fax to Larry stating that he was no longer willing to sell him Blackacre. Larry received this letter before Moe received Larry’s letter agreeing to the higher price. Larry then called Moe to confirm his willingness to buy Blackacre for $275,000, but Moe said he was now unwilling to sell Blackacre to him. -

Continuous and Apparent Easement

Continuous And Apparent Easement tristichicSickening Westleigh Spencer smilingsolaces, some his sleeving tracing soled removably! ballyrag uphill. Levon grangerizing imaginably. Imputable and He and continuous, our service provides information in various types of dismemberments of setbacks and her. Article 615 Easements may be continuous or discontinuous apparent or nonapparent Continuous easements are deficient the order of which discourage or. Any pet who is not wish to contribute may exempt loan by renouncing the easement for the below of the others. Easements Neighborhood and daily of way Notaries of France. An apparent by continuing to establish in no feasible method of lands are there was retained an office or impliedly granted for instance, listing all three descriptions referred to. Fourthly, maintain, represent the petitioner to inquire is the relatives of Maria Florentino as evidence when she died. Can he was held to meet this type is apparent sign, whose use may be found on private use made apparent easement? Purchasers of severance; minority require help they benefit of dominant tenement from being interests in determining implication, if your profile web property interest in efficiently handling varied. British Columbia, which service became really true easement upon which death. 192 the court observed that An easement is harsh if its existence is indicated by signs which might be seen him known right a careful inspection by an person ordinarily conversant with human subject The award further observed that A continuous or apparent easement is either a curtain or enjoyed by means declare a fixture. When necessity are necessary to determine whether a declaratory judgment, or necessary for excessive use requirements of aqueduct for. -

1. Blackacre and Greenacre May Constitute Bonnie and Wally's Homestead Property

Q6 - July 2017 - Selected Answer 1 6) 1. Blackacre and Greenacre may constitute Bonnie and Wally's homestead property. The issue is whether two tracts of noncontiguous tracts of land may qualify as a rural homestead. Under Texas Law, a family may have an urban or rural homestead. An urban homestead exists where up to 10 contiguous acres within the city limits, or platted subdivision are used as a primary residence, are provided police and volunteer or paid fire protection, and at least three of the following services: water, natural gas, electricity, sewer, storm sewer. A homestead that does not qualify as urban is considered rural. A family may hold up to 200 non contiguous acres as a rural homestead. Here, Bonnie and Wally built a home on Blackacre, and Bonnie later inherited Greenacre which was a tract of land nearby and in the same county. Together, the tracts equal 125 acres and would be within the alloted amount for a rural homestead. So long as Bonnie and Wally maintain their primary residence on a part of the non-contiguous acres, the entirety of both tracts may be held as homestead where the land is used for the support of the family. 2. No, Big Oil's oil and gas lease is not valid. The issue is whether Wally had the right to, and did, validly grant an oil and gas lease to the covering Blackacre without Bonnie joined. Bonnie and Wally are married and they purchased Blackacre and built there home on it. If Blackacre is a homestead, both parties would have to be on an instrument conveying the property. -

Governing Water: the Semicommons of Fluid Property Rights

GOVERNING WATER: THE SEMICOMMONS OF FLUID PROPERTY RIGHTS Henry E. Smith* This Article applies an information-cost theory of property to water law. Because of its fluidity, exclusion is difficult in the case of water and gives way to rule of proper use, i.e., governance regimes. Looking at water through this lens reveals that prior appropriation employs more governance and riparianism rests more on a foundation of exclusion than is commonly thought. The development of increasing amounts of exclusion and governance are both compatible with a broadly Demsetzian account that is sensitive to the nature of the resource. Moreover, hybrids between prior appropriation and riparianism are not anomalous. Exclusion strategies based on boundaries and quantification allow for rights to be formal and modular, but this approach is particularly challenging in the case of water and other fugitive resources. The challenges of exclusion that water and other fugitive resources present often lead to a semicommons in which elements of private and common property both coexist and interact. INTRODUCTION Water is a fugitive resource that is expected to fulfill many human needs, including drinking and household uses, raising farm animals, irrigation, mining, power, manufacturing, sewage, navigation, wildlife, recreation, aesthetic, and environmental values. Some of these uses require withdrawals of water, some involve discharges into water, and others presuppose some quantity of water left in place. To serve all these ends, many parties require access to water, and at the same time water itself moves easily and replenishes partially (and not completely predictably) as part of the hydrologic cycle. Given the heterogeneity of uses, the costliness of measuring and monitoring them, and the difficulties in predicting flows of water from year to year, water is among the most challenging of resources from the point of view of property law. -

Blackacre Sydney University Law Society Annual Yearbook 2017

Blackacre Sydney University Law Society Annual Yearbook 2017 Editor-in-Chief Ryan Hunter Editors Elizabeth Kim Beverly Parungao Anoushka William Illustrations & Cover Dora Cheung SULS Publications Director Emily Shen Contributions by Rachael Buckland Rohan Barmanray John Fennel Alyssa Glass Gaston Gration Jenna Ying Lim Helena Liu Tanvi Patel Alexi Polden Rachel Stokker Calida Tang Mary Ward Elaine Yeo Generous Anonymous Authors & SULS’ Many Many Photographers Blackacre is made possible by the efforts of a small group of Sydney Law School Students, and published under the auspices of the Sydney University Law Society and the University of Sydney Union. The opinions expressed in individual articles of Blackacre belong to their authors. If you are unhappy with any of the material in Blackacre please refer to the editors’ lack of salary and your lack of humour. Blackacre is published on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. Blackacre acknowledges those people as the traditional owners and custodians of this land, sovereignty to which was never ceded. Welcome to Blackacre; Farewell to 2017 As another year comes to a close, and another graduating class Journal called us in 2013 at the height of the infamous prepares to pass out of our care into the wide world beyond “Corporate Law Exam Fire Alarm Incident”). I have found our sandstone walls, I usually experience a mixture of relief myself embroiled in quite a few of these kinds of incidents and sadness. Relief to see another year survived; sadness to during my time as Dean of this illustrious law school, and they see the familiar faces of the graduating cohort disappear, off to have taught me a number of things. -

QUESTION 1 Purchaser Acquired Blackacre from Seller in 1988

QUESTION 1 Purchaser acquired Blackacre from Seller in 1988. Seller had purchased the property in 1978. Throughout Seller's ownership, Blackacre had been described by a metes and bounds legal description, which Seller believed to include an island within a stream. Seller conveyed title to Blackacre to Purchaser through a special warranty deed describing Blackacre with the same legal description through which Seller acquired it. At all times while Seller owned Blackacre, she thought she owned the island. In 1978, she built a foot bridge to the island to allow her to drive a tractor mower on it. During the summer, she regularly mowed the grass and maintained a picnic table on the island. Upon acquiring Blackacre, Purchaser continued to mow the grass and maintain the picnic table during the summer. In 1994, Neighbor, who owns the property adjacent to Blackacre, had a survey done of his property (the accuracy of which is not disputed) which shows that he owns the island. In 1998, Neighbor demanded that Purchaser remove the picnic table and stop trespassing on the island. QUESTION: Discuss any claims which Purchaser might assert to establish his right to the island or which he may have against Seller. DISCUSSION FOR QUESTION 1 I. Mr. Plaintiffs Claims versus Mr. Neighbor One who maintains continuous, exclusive, open, and adverse possession of real property for the requisite statutory period may obtain title thereto under the principle of adverse possession. Edie v. Coleman, 235 Mo. App. 1289, 141 S.W. 2d 238 (1940), Vade v. Sickler, 118 Colo. 236, 195 P.2d 390 (1948). -

A High-Voltage Conflict on Blackacre: Reorienting Utility Easement Rights for Electric Reliability Brian S

A High-Voltage Conflict on Blackacre: Reorienting Utility Easement Rights for Electric Reliability Brian S. Tomasovic* Introduction.....................................................................................................2 I. The Need for UVM in the Twenty-First Century.......................................5 A. The Basic Justifications for UVM ..........................................................6 1. Preventing Power Outages .................................................................6 2. Preventing Fires ................................................................................10 3. Public Safety ......................................................................................12 B. Expanding Infrastructure and Growing Risk Exposure ....................12 C. Modernization of UVM........................................................................15 D. Objections to UVM ..............................................................................19 1. Community Objections.....................................................................20 2. Property Owner Objections..............................................................22 3. The Customer Refusal ......................................................................24 II. Overview of the Regulatory Environment for UVM..............................26 A. Federal Developments .........................................................................27 B. State Developments..............................................................................31 -

Exception and Reservation of Easements

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1924 Exception and Reservation of Easements Harry A. Bigelow J. W. Madden Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Harry A. Bigelow & J. W. Madden, "Exception and Reservation of Easements," 38 Harvard Law Review 180 (1924). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARVARD LAW REVIEW EXCEPTION AND RESERVATION OF EASEMENTS. T HE exact relation in our law between the functions of the reservation and the exception in the creation of easements, where one of two tracts or a part of one tract is conveyed by the owner to a third person, is the subject of marked differences of opinion on the part of the courts. It is the purpose of this paper to examine historically and analytically some of the prob- lems raised in such a case. Chief Justice Tindal said: "It is to be observed that a right of way cannot, in strictness, be made the subject either of ex- ception or reservation." 1 If this were an accurate statement of the law, there would, of course, be nothing to discuss under the title of this paper. But conveyancers and laymen have, in numerous instances, attempted to create easements in the manner suggested in the title, and the" courts have frequently used language in flat contradiction to that quoted. -

Two Cheers for the Bundle-Of-Sticks Metaphor, Three Cheers for Merrill

Discuss this article at Journaltalk: http://journaltalk.net/articles/5732 ECON JOURNAL WATCH 8(3) September 2011: 215-222 Two Cheers for the Bundle-of- Sticks Metaphor, Three Cheers for Merrill and Smith Robert C. Ellickson1 LINK TO ABSTRACT Property rights in a particular resource commonly are splintered among different owners. To account for this possibility, some legal commentators refer to the maximal set of ownership entitlements in a specific asset as a bundle that can potentially be disaggregated through consensual transactions or otherwise. This conception is often expressed in terms of a bundle of rights. For reasons that will become clear, I instead invoke the image of a “bundle of sticks,” an only slightly less popular metaphor for the same idea. Justice Benjamin Cardozo, a premier judicial wordsmith, is conventionally credited with having first likened a set of full property entitlements to a bundle of firewood.2 And in several opinions, Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States have invoked this image to describe the fullest possible set of private property rights.3 In this usage, bundle of sticks is a metaphor. Metaphors, unlike synonyms, are invariably inexact and therefore potentially misleading. I anticipate that contribu- tors to this symposium will highlight two types of mischief that the metaphor may cause. First, the conception that property rights come in bundles that are easily fragmented may be descriptively inapt because various legal rules limit a property 1. Yale Law School, New Haven, CT 06511. 2. “The bundle of power and privileges to which we give the name of ownership is not constant through the ages.