The Creation of President Ford's Clemency Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2/21-VFW Newsletter (Page 1)

February 21 General Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller 14631 MINNIEVILLE ROAD • DALE CITY, VIRGINIA 22193 • 703.670.4124 www.vfw1503.org CANTEEN HOURS: Sunday / Monday / Wednesday 12 Noon - 11 PM Tuesday / Thursday / Saturday 12 Noon - 12 Midnight • Friday 12 Noon - 2 AM COMMANDER’S CORNER POST OFFICERS Post Commander . Tom Levitt Comrades and Auxiliary Members, Senior Vice . Bernie Carter We end our first month of the new year Junior Vice . Ben Guinan hoping that things are beginning to turn around Quartermaster . Tim Brown Judge Advocate. Star Martinez for us in this pandemic as we see vaccines being Surgeon . Robert Adamczyk administered. Despite a significant spike in COVID cases over the Chaplain. Ed Bennett holidays there is a belief that the vaccine will help us flatten the 3 Year Trustee . Tom Gimble 2 Year Trustee . Ron Laney curve and begin trending downward. I know we will all be happy 1 Year Trustee. John Dodge to get back some normalcy in our lives and at our post!! Adjutant . Randy Coker This past month we celebrated the life of Martin Luther King Jr. Service Officer . Carl Richardson Asst. Service Officer . Tami Brown and his contributions to the civil rights movement. Normally on House Committee Chairman. Joe Saitta that day we host a meal in his honor which we failed to do this Past Commander . Thomas Williams, Jr. year. An honest mistake, but a mistake nonetheless. As the Commander everything that happens or fails to happen in the post is my responsibility. For this failure I take responsibility and apologize to all who may have felt slighted or offended. -

4. IOWA Iowa Is the State Famous for Holding Presidential Caucuses Rather Than a Presidential Primary. There Is a Good Reason F

4. IOWA Iowa is the state famous for holding presidential caucuses rather than a presidential primary. There is a good reason for that. The state of New Hampshire has a tradition of holding the first presidential primary. In fact, New Hampshire has a law requiring that the New Hampshire primary be one week before the presidential primary of any other state. By scheduling caucuses rather than a primary, Iowa is able to hold its caucuses ahead of New Hampshire and thereby escape the political ire of New Hampshirites. Iowa also thus prevents New Hampshire from scheduling its primary one week ahead of the presidential caucuses in Iowa. That is what that famous New Hampshire law would require if Iowa held a primary. It was in 1972 that Iowa first scheduled its "First In The Nation" presidential caucuses. Four years later, in 1976, the Iowa caucuses were propelled to major importance when Jimmy Carter, a little-known former governor of Georgia, devoted virtually a year of his life to campaigning in Iowa. Carter's surprise victory in the Iowa caucuses made him the instant front-runner for the Democratic nomination. It was an advantage which Carter exploited so well he was eventually elected president of the United States. But there is also a downside to the Iowa caucuses for presidential hopefuls. Iowa can be the burial ground for a candidacy instead of the launching pad. That is what happened to U.S. Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts in 1980 when he challenged incumbent President Jimmy Carter for the Democratic nomination. President Carter polled 59 percent of the Iowa caucuses vote to 31 percent for Kennedy. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

SAY NO to the LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES and CRITICISM of the NEWS MEDIA in the 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the Faculty

SAY NO TO THE LIBERAL MEDIA: CONSERVATIVES AND CRITICISM OF THE NEWS MEDIA IN THE 1970S William Gillis Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Journalism, Indiana University June 2013 ii Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee David Paul Nord, Ph.D. Mike Conway, Ph.D. Tony Fargo, Ph.D. Khalil Muhammad, Ph.D. May 10, 2013 iii Copyright © 2013 William Gillis iv Acknowledgments I would like to thank the helpful staff members at the Brigham Young University Harold B. Lee Library, the Detroit Public Library, Indiana University Libraries, the University of Kansas Kenneth Spencer Research Library, the University of Louisville Archives and Records Center, the University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, the Wayne State University Walter P. Reuther Library, and the West Virginia State Archives and History Library. Since 2010 I have been employed as an editorial assistant at the Journal of American History, and I want to thank everyone at the Journal and the Organization of American Historians. I thank the following friends and colleagues: Jacob Groshek, Andrew J. Huebner, Michael Kapellas, Gerry Lanosga, J. Michael Lyons, Beth Marsh, Kevin Marsh, Eric Petenbrink, Sarah Rowley, and Cynthia Yaudes. I also thank the members of my dissertation committee: Mike Conway, Tony Fargo, and Khalil Muhammad. Simply put, my adviser and dissertation chair David Paul Nord has been great. Thanks, Dave. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents, who have provided me with so much support in so many ways over the years. -

Eligibility Guide.Pdf

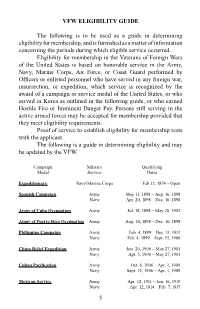

VFW ELIGIBILITY GUIDE The following is to be used as a guide in determining eligibility for membership, and is furnished as a matter of information concerning the periods during which eligible service occurred. Eligibility for membership in the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States is based on honorable service in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard performed by Officers or enlisted personnel who have served in any foreign war, insurrection, or expedition, which service is recognized by the award of a campaign or service medal of the United States, or who served in Korea as outlined in the following guide, or who earned Hostile Fire or Imminent Danger Pay. Persons still serving in the active armed forces may be accepted for membership provided that they meet eligibility requirements. Proof of service to establish eligibility for membership rests with the applicant. The following is a guide in determining eligibility and may be updated by the VFW. Campaign Military Qualifying Medal Service Dates Expeditionary Navy/Marine Corps Feb 12, 1874 – Open Spanish Campaign Army May 11, 1898 – Aug. 16, 1898 Navy Apr. 20, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Army of Cuba Occupation Army Jul. 18, 1898 – May 20, 1902 Army of Puerto Rico Occupation Army Aug. 14, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Philippine Campaign Army Feb. 4, 1899 – Dec. 31, 1913 Navy Feb. 4, 1899 – Sept. 15, 1906 China Relief Expedition Army Jun. 20, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Navy Apr. 5, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Cuban Pacification Army Oct. 6, 1906 – Apr. 1, 1909 Navy Sept. 12, 1906 – Apr. -

Whpr19740819-010

-., f'. Digitized from Box 1 of the White House Press Releases at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUGUST 19, 1974 , OFFICE OF THE WHITE HOUSE PRESS SECRETARY (Chicago, Illinois) THE WHITE HOUSE ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT TO THE 7STH CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS or FOREIGN WARS CONRAD HILTON HOTEL 11:38 A.M. CDT Commander Ray Soden, Governor Walker, my former members or former colleagues of the United States Congress, my fellow members of the Veterans of Foreign Wars: Let me express my deepest gratitude for your extremely warm welcome and may I say to Mayor Daley, and to all the wonderful people of Chicago who have done an unbelievable job in welcoming Betty and myself to Chicago, we are most grateful. I have a sneaking suspicion that Mayor Daley and the people of Chicago knew that Betty was born in Chicago. Needless to say, I deeply appreciate your medal and the citation on my first trip out of Washington as your President. I hope that in the months ahead I can justify your faith in making the citation and the award available to me. It is good to be back in Chicago among people from all parts of our great Nation to take part in this 75th Annual convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. As a proud member of Old Kent Post VFW 830, let me talk today about some of the work facing veterans - and all Americans -- the issues of world peace and national unity. Speaking of national unity,. let me.quick;Ly point out that I am also a proud member of the American Legion and the AMVETS. -

Gerald Ford's Clemency Board: Revisited And

Gerald Ford’s Clemency Board: Revisited and Reassessed by Alan Jaroslovsky A thesis submitted to Sonoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Committee Members: Dr. Steve Estes, Chair Dr. Michelle Jolly Dr. Margaret Miller October 22, 2019 copyright © 2019 By Alan Jaroslovsky ii Gerald Ford’s Clemency Board: Revisited and Reassessed Thesis by Alan Jaroslovsky ABSTRACT Intended mainly as a vehicle for rehabilitating draft evaders after the Vietnam War, the Presidential Clemency Board (“PCB”) was largely an orphan of the Ford presidency. Created in the wake of the Nixon pardon as an unpopular compromise between those who opposed any sort of clemency and those who urged a general amnesty, the PCB was plagued by attacks from both the right and the left, internal dissent, and numerous administrative difficulties. Little has been written about the PCB in the four decades since it concluded its work, and those historians who have evaluated it have reached the conclusion that it was largely unsuccessful. Using recently-available records and notes of Ford’s advisors and PCB participants, this thesis will demonstrate that while the PCB did little to accomplish its stated goal of “healing the nation” and was boycotted by the draft evaders who were its primary intended beneficiaries, it was nonetheless a bureaucratic achievement of some note and an incidental success for its least important beneficiaries, common soldiers who had been cast aside by American society. MA Program: History Sonoma State University Date: October 22, 2019 iv Preface A historian might say there are three aspects of an interesting life: to participate in history, to be aware of it at the time, and to live long enough to give the experience some perspective. -

Doers Dreamers Ors Disrupt &

POLITICO.EU DECEMBER 2018 Doers Dreamers THE PEOPLE WHO WILL SHAPE & Disrupt EUROPE IN THE ors COMING YEAR In the waves of change, we find our true drive Q8 is an evolving future proof company in this rapidly changing age. Q8 is growing to become a broad mobility player, by building on its current business to provide sustainable ‘fuel’ and services for all costumers. SOMEONE'S GOT TO TAKE THE LEAD Develop emission-free eTrucks for the future of freight transport. Who else but MAN. Anzeige_230x277_eTrucks_EN_181030.indd 1 31.10.18 10:29 11 CONTENTS No. 1: Matteo Salvini 8 + Where are Christian Lindner didn’t they now? live up to the hype — or did he? 17 The doers 42 In Germany, Has the left finally found its a new divide answer to right-wing nationalism? 49 The dreamers Artwork 74 85 Cover illustration by Simón Prades for POLITICO All illustrated An Italian The portraits African refugees face growing by Paul Ryding for unwelcome resentment in the country’s south disruptors POLITICO 4 POLITICO 28 SPONSORED CONTENT PRESENTED BY WILFRIED MARTENS CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN STUDIES THE EAST-WEST EU MARRIAGE: IT’S NOT TOO LATE TO TALK 2019 EUROPEAN ELECTIONS ARE A CHANCE TO LEARN FROM LESSONS OF THE PAST AND BRING NATIONS CLOSER TOGETHER BY MIKULÁŠ DZURINDA, PRESIDENT, WILFRIED MARTENS CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN STUDIES The East-West relationship is like the cliché between an Eastern bride and a Western man. She is beautiful but poor and with a slightly troubled past. He is rich and comfortable. The West which feels underappreciated and the East, which has the impression of not being heard. -

Remarks at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention in Phoenix, Arizona August 17, 2009

Aug. 15 / Administration of Barack Obama, 2009 NOTE: The President spoke at 3:44 p.m. at troduced the President, his wife Sonji, and Central High School. In his remarks, he re- their son Thomas; Tilman Bishop, vice chair of ferred to Nathan Wilkes, principal network ar- the board of regents, University of Colorado; chitect, Virtela Communications, Inc., who in- and Sen. Johnny Isakson. Remarks at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention in Phoenix, Arizona August 17, 2009 Thank you. Please, be seated. Thank you so our harbor was bombed, you battled across much. Commander Gardner, thank you for rocky Pacific islands and stormed the beaches your introduction and for your lifetime of ser- of Europe, marching across a continent—my vice. I was proud to welcome Glen and your own grandfather and uncle among your executive director, Bob Wallace, to the Oval ranks—liberating millions and turning ene- Office just before the Fourth of July, and I mies into allies. look forwarding to working with your next When communism cast its shadow across so commander, Tommy Tradewell. I want to also much of the globe, you stood vigilant in a long acknowledge Jean Gardner and Sharon cold war, from an airlift in Berlin to the moun- Tradewell, as well as Dixie Hild and Jan Tittle tains of Korea to the jungles of Vietnam. and all the spouses and family of the Ladies When that cold war ended and old hatreds Auxiliary. America honors your service as well. emerged anew, you turned back aggression Also Governor Jan Brewer is here, of Arizo- from Kuwait to Kosovo. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881-1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6gn7b51j Author Myers, Eric Dennis Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Eric Dennis Myers 2013 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 by Eric Dennis Myers Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Joan Waugh, Chair The dissertation is a historical biography of Smedley Darlington Butler (1881-1940), a decorated soldier and critic of war profiteering during the 1930s. A two-time Congressional Medal of Honor winner and son of a powerful congressman, Butler was one of the most prominent military figures of his era. He witnessed firsthand the American expansionism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, participating in all of the major conflicts and most of the minor ones. Following his retirement in 1931, Butler became an outspoken critic of American intervention, arguing in speeches and writings against war profiteering and the injustices of expansionism. His critiques represented a wide swath of public opinion at the time – the majority of Americans supported anti-interventionist policies through 1939. Yet unlike other members of the movement, Butler based his theories not on abstract principles, but on experiences culled from decades of soldiering: the terrors and wasted resources of the battlefield, ! ""! ! the use of the American military to bolster corrupt foreign governments, and the influence of powerful, domestic moneyed interests. -

Tom Judd & Sheila Lee-Eiler Elected to Lead AZ VFW in 2019-2020

52 Continuous Years of 100% Membership Issue 52-1 September 2019 Tom Judd & Sheila Lee-Eiler Elected to Lead AZ VFW in 2019-2020 Tom A. Judd was elected Sheila Lee-Eiler was elected as State Commander of the Vet- the Department of Arizona’s Pres- erans of Foreign Department ident in June of 2019. She joined of Arizona on June 1, 2019. the VFW Auxiliary in March 2008 Tom was born in Spring- at the Sandy CoorPost 1433 in erville, Arizona and grew up Glendale, Az., under the eligibility in Alpine, Arizona. He was in of her father, Chester H. Lee Sr.A the United States Navy from Korean War Army Veteran who 1970 to 1974 as an Interior earned 4 Bronze Stars while in ser- Communications Electrician vice. on board the USS Leonard F. Sheila has served her aux- 0DVRQ''ZLWKWZRWULSVWR9LHWQDPDVJXQ¿UH iliary as President 2009 – 2012. She also served as the support, Yankee Station, Sar and Operation Line- District 3 President 2012 – 2015. She has served as Vet- backer Two. Operation Linebacker Two they were erans and Family Support, Scholarship and Member- the decoy as they were the older ship. In recognition ship programs chairman for the Department of Arizona. of his service he received the National Defense Ser- Where she won National awards for all 3 chairmanships. vice Metal, Vietnam Service Metal and the Republic Sheila is married to Dept. of AZ, VFW Sr. Vice Com- of Vietnam Campaign Metal. He retired from Arizo- PDQGHU-HɣUH\(LOHU5HWLUHG1DY\6XEPDULQH9HWHUDQ na Public Service Company in 2016 after 25 years. -

PA VFW Honors Local Public Safety Professional the Pennsylvania

PA VFW Honors Local Public Safety Professional The Pennsylvania Department of Veterans of Foreign Wars recently recognized recipients of its annual Public Safety Awards. Each year, the Pennsylvania VFW presents awards to an outstanding fire fighter, police officer and emergency medical technician to honor them for the critical roles they fill as first responders. This year’s Award winners are residents of Middletown, Lenox/Clifford Township and Erie. “The VFW has a long tradition of honoring and supporting veterans for their role in protecting and preserving freedom. We also proudly honor and support public safety personnel who put their lives on the line every day to protect us where we live, work and play,” said VFW State Commander Thomas M. Hanzes, a Vietnam War veteran. “Americans are able to enjoy life knowing that there are dedicated professionals who train and work hard to assist persons facing disasters and life- threatening situations. We thank our award recipients for answering the call to fill vital roles. Citizens can enjoy live confidently while our fire, police and EMT personnel have their backs.” • “PA VFW Emergency Medical Technician of the Year”: Phillip P. Price, an emergency medical technician with the Clifford Township Volunteer Fire Department, sponsored by VFW Post 8488 and District 14. He has been involved in emergency services since 16 years of age. In the mid- 1970s, he trained as an emergency medical technician, one of the first to do so in Susquehanna County. Over the past three years, he has responded to more than 850 ambulance calls totaling more than 2,400 hours of service.