A President with a Purpose Leadership Lessons from Gerald L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2/21-VFW Newsletter (Page 1)

February 21 General Lewis B. “Chesty” Puller 14631 MINNIEVILLE ROAD • DALE CITY, VIRGINIA 22193 • 703.670.4124 www.vfw1503.org CANTEEN HOURS: Sunday / Monday / Wednesday 12 Noon - 11 PM Tuesday / Thursday / Saturday 12 Noon - 12 Midnight • Friday 12 Noon - 2 AM COMMANDER’S CORNER POST OFFICERS Post Commander . Tom Levitt Comrades and Auxiliary Members, Senior Vice . Bernie Carter We end our first month of the new year Junior Vice . Ben Guinan hoping that things are beginning to turn around Quartermaster . Tim Brown Judge Advocate. Star Martinez for us in this pandemic as we see vaccines being Surgeon . Robert Adamczyk administered. Despite a significant spike in COVID cases over the Chaplain. Ed Bennett holidays there is a belief that the vaccine will help us flatten the 3 Year Trustee . Tom Gimble 2 Year Trustee . Ron Laney curve and begin trending downward. I know we will all be happy 1 Year Trustee. John Dodge to get back some normalcy in our lives and at our post!! Adjutant . Randy Coker This past month we celebrated the life of Martin Luther King Jr. Service Officer . Carl Richardson Asst. Service Officer . Tami Brown and his contributions to the civil rights movement. Normally on House Committee Chairman. Joe Saitta that day we host a meal in his honor which we failed to do this Past Commander . Thomas Williams, Jr. year. An honest mistake, but a mistake nonetheless. As the Commander everything that happens or fails to happen in the post is my responsibility. For this failure I take responsibility and apologize to all who may have felt slighted or offended. -

The Butz Stops Here: Why the Food Movement Needs to Rethink Agricultural History

Journal of Food Law & Policy Volume 13 | Number 1 Article 7 2017 The utB z Stops Here: Why the Food Movement Needs to Rethink Agricultural History Nathan A. Rosenberg University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Bryce Wilson Stucki United States Census Bureau Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jflp Part of the Food and Drug Law Commons Recommended Citation Rosenberg, Nathan A. and Stucki, Bryce Wilson (2017) "The utzB Stops Here: Why the Food Movement Needs to Rethink Agricultural History," Journal of Food Law & Policy: Vol. 13 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/jflp/vol13/iss1/7 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Food Law & Policy by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ROSENBERG STUCKI FORMATTED (DO NOT DELETE) 6/20/2017 1:31 PM The Butz Stops Here: Why the Food Movement Needs to Rethink Agricultural History Nathan A. Rosenberg & Bryce Wilson Stucki** After Donald Trump’s surprise victory over Hillary Clinton, commentators and journalists turned their attention to rural America, where Trump won three times as many votes as his opponent, in order to understand what had just happened.1 They wrote about forgotten places: small towns populated by opioid addicts,2 dying Rust Belt cities with abandoned factories at their centers,3 and mountain hamlets populated by xenophobes and racists.4 These writers described a conservatism so total and inexplicable it seemed part of the landscape. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

Eligibility Guide.Pdf

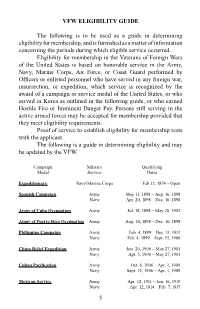

VFW ELIGIBILITY GUIDE The following is to be used as a guide in determining eligibility for membership, and is furnished as a matter of information concerning the periods during which eligible service occurred. Eligibility for membership in the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States is based on honorable service in the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard performed by Officers or enlisted personnel who have served in any foreign war, insurrection, or expedition, which service is recognized by the award of a campaign or service medal of the United States, or who served in Korea as outlined in the following guide, or who earned Hostile Fire or Imminent Danger Pay. Persons still serving in the active armed forces may be accepted for membership provided that they meet eligibility requirements. Proof of service to establish eligibility for membership rests with the applicant. The following is a guide in determining eligibility and may be updated by the VFW. Campaign Military Qualifying Medal Service Dates Expeditionary Navy/Marine Corps Feb 12, 1874 – Open Spanish Campaign Army May 11, 1898 – Aug. 16, 1898 Navy Apr. 20, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Army of Cuba Occupation Army Jul. 18, 1898 – May 20, 1902 Army of Puerto Rico Occupation Army Aug. 14, 1898 – Dec. 10, 1898 Philippine Campaign Army Feb. 4, 1899 – Dec. 31, 1913 Navy Feb. 4, 1899 – Sept. 15, 1906 China Relief Expedition Army Jun. 20, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Navy Apr. 5, 1900 – May 27, 1901 Cuban Pacification Army Oct. 6, 1906 – Apr. 1, 1909 Navy Sept. 12, 1906 – Apr. -

Whpr19740819-010

-., f'. Digitized from Box 1 of the White House Press Releases at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUGUST 19, 1974 , OFFICE OF THE WHITE HOUSE PRESS SECRETARY (Chicago, Illinois) THE WHITE HOUSE ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT TO THE 7STH CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS or FOREIGN WARS CONRAD HILTON HOTEL 11:38 A.M. CDT Commander Ray Soden, Governor Walker, my former members or former colleagues of the United States Congress, my fellow members of the Veterans of Foreign Wars: Let me express my deepest gratitude for your extremely warm welcome and may I say to Mayor Daley, and to all the wonderful people of Chicago who have done an unbelievable job in welcoming Betty and myself to Chicago, we are most grateful. I have a sneaking suspicion that Mayor Daley and the people of Chicago knew that Betty was born in Chicago. Needless to say, I deeply appreciate your medal and the citation on my first trip out of Washington as your President. I hope that in the months ahead I can justify your faith in making the citation and the award available to me. It is good to be back in Chicago among people from all parts of our great Nation to take part in this 75th Annual convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. As a proud member of Old Kent Post VFW 830, let me talk today about some of the work facing veterans - and all Americans -- the issues of world peace and national unity. Speaking of national unity,. let me.quick;Ly point out that I am also a proud member of the American Legion and the AMVETS. -

Remarks at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention in Phoenix, Arizona August 17, 2009

Aug. 15 / Administration of Barack Obama, 2009 NOTE: The President spoke at 3:44 p.m. at troduced the President, his wife Sonji, and Central High School. In his remarks, he re- their son Thomas; Tilman Bishop, vice chair of ferred to Nathan Wilkes, principal network ar- the board of regents, University of Colorado; chitect, Virtela Communications, Inc., who in- and Sen. Johnny Isakson. Remarks at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Convention in Phoenix, Arizona August 17, 2009 Thank you. Please, be seated. Thank you so our harbor was bombed, you battled across much. Commander Gardner, thank you for rocky Pacific islands and stormed the beaches your introduction and for your lifetime of ser- of Europe, marching across a continent—my vice. I was proud to welcome Glen and your own grandfather and uncle among your executive director, Bob Wallace, to the Oval ranks—liberating millions and turning ene- Office just before the Fourth of July, and I mies into allies. look forwarding to working with your next When communism cast its shadow across so commander, Tommy Tradewell. I want to also much of the globe, you stood vigilant in a long acknowledge Jean Gardner and Sharon cold war, from an airlift in Berlin to the moun- Tradewell, as well as Dixie Hild and Jan Tittle tains of Korea to the jungles of Vietnam. and all the spouses and family of the Ladies When that cold war ended and old hatreds Auxiliary. America honors your service as well. emerged anew, you turned back aggression Also Governor Jan Brewer is here, of Arizo- from Kuwait to Kosovo. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881-1940 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6gn7b51j Author Myers, Eric Dennis Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Eric Dennis Myers 2013 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Soldier at Heart: The Life of Smedley Butler, 1881 - 1940 by Eric Dennis Myers Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Joan Waugh, Chair The dissertation is a historical biography of Smedley Darlington Butler (1881-1940), a decorated soldier and critic of war profiteering during the 1930s. A two-time Congressional Medal of Honor winner and son of a powerful congressman, Butler was one of the most prominent military figures of his era. He witnessed firsthand the American expansionism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, participating in all of the major conflicts and most of the minor ones. Following his retirement in 1931, Butler became an outspoken critic of American intervention, arguing in speeches and writings against war profiteering and the injustices of expansionism. His critiques represented a wide swath of public opinion at the time – the majority of Americans supported anti-interventionist policies through 1939. Yet unlike other members of the movement, Butler based his theories not on abstract principles, but on experiences culled from decades of soldiering: the terrors and wasted resources of the battlefield, ! ""! ! the use of the American military to bolster corrupt foreign governments, and the influence of powerful, domestic moneyed interests. -

Tom Judd & Sheila Lee-Eiler Elected to Lead AZ VFW in 2019-2020

52 Continuous Years of 100% Membership Issue 52-1 September 2019 Tom Judd & Sheila Lee-Eiler Elected to Lead AZ VFW in 2019-2020 Tom A. Judd was elected Sheila Lee-Eiler was elected as State Commander of the Vet- the Department of Arizona’s Pres- erans of Foreign Department ident in June of 2019. She joined of Arizona on June 1, 2019. the VFW Auxiliary in March 2008 Tom was born in Spring- at the Sandy CoorPost 1433 in erville, Arizona and grew up Glendale, Az., under the eligibility in Alpine, Arizona. He was in of her father, Chester H. Lee Sr.A the United States Navy from Korean War Army Veteran who 1970 to 1974 as an Interior earned 4 Bronze Stars while in ser- Communications Electrician vice. on board the USS Leonard F. Sheila has served her aux- 0DVRQ''ZLWKWZRWULSVWR9LHWQDPDVJXQ¿UH iliary as President 2009 – 2012. She also served as the support, Yankee Station, Sar and Operation Line- District 3 President 2012 – 2015. She has served as Vet- backer Two. Operation Linebacker Two they were erans and Family Support, Scholarship and Member- the decoy as they were the older ship. In recognition ship programs chairman for the Department of Arizona. of his service he received the National Defense Ser- Where she won National awards for all 3 chairmanships. vice Metal, Vietnam Service Metal and the Republic Sheila is married to Dept. of AZ, VFW Sr. Vice Com- of Vietnam Campaign Metal. He retired from Arizo- PDQGHU-HɣUH\(LOHU5HWLUHG1DY\6XEPDULQH9HWHUDQ na Public Service Company in 2016 after 25 years. -

PA VFW Honors Local Public Safety Professional the Pennsylvania

PA VFW Honors Local Public Safety Professional The Pennsylvania Department of Veterans of Foreign Wars recently recognized recipients of its annual Public Safety Awards. Each year, the Pennsylvania VFW presents awards to an outstanding fire fighter, police officer and emergency medical technician to honor them for the critical roles they fill as first responders. This year’s Award winners are residents of Middletown, Lenox/Clifford Township and Erie. “The VFW has a long tradition of honoring and supporting veterans for their role in protecting and preserving freedom. We also proudly honor and support public safety personnel who put their lives on the line every day to protect us where we live, work and play,” said VFW State Commander Thomas M. Hanzes, a Vietnam War veteran. “Americans are able to enjoy life knowing that there are dedicated professionals who train and work hard to assist persons facing disasters and life- threatening situations. We thank our award recipients for answering the call to fill vital roles. Citizens can enjoy live confidently while our fire, police and EMT personnel have their backs.” • “PA VFW Emergency Medical Technician of the Year”: Phillip P. Price, an emergency medical technician with the Clifford Township Volunteer Fire Department, sponsored by VFW Post 8488 and District 14. He has been involved in emergency services since 16 years of age. In the mid- 1970s, he trained as an emergency medical technician, one of the first to do so in Susquehanna County. Over the past three years, he has responded to more than 850 ambulance calls totaling more than 2,400 hours of service. -

Veterans of Foreign Wars Auxiliary UNWAVERING SUPPORT for UNCOMMON HEROES®

Veterans of Foreign Wars Auxiliary UNWAVERING SUPPORT FOR UNCOMMON HEROES® www.vfwauxiliary.org We are the nation’s oldest veterans’ service organization auxiliary. For more than 100 years, we have been serving veterans, the military and their families in countless ways. Millions of hours, millions of dollars and millions of tributes. THIS IS WHO WE ARE. VFW Auxiliary members are the relatives of those who have served in overseas combat. I am an Auxiliary member because our programs help veterans in need, preserve our nation’s patriotic traditions and educate youth. - Jeanene B. VETERANS & HOSPITAL FAMILY SUPPORT Value of goods and services Auxiliaries provided to veterans, Amount spent by Auxiliaries on active-duty service members and all hospital projects and items $6.2 their families. $2.7 MILLION MILLION Auxiliaries provided aid to 632,493 veterans, active-duty military, Number of hours served in and their families in all 50 states VA medical centers, hospitals, nursing homes and veterans homes The majority of Auxiliaries took part 2,719 in veteran and military suicide Number of Auxiliaries that hosted awareness and prevention education or sponsored events at VA medical centers, hospitals, nursing homes and veterans homes Thousands of Auxiliaries nationwide participated in or sponsored events 44,638 or projects for active-duty troops Number of Auxiliary members and their families who volunteered for the Hospital Program LEGISLATIVE Number of contacts made to help pass or block important bills 119,613 www.vfwauxiliary.org [email protected] facebook.com/VFWAuxiliary “I love supporting and honoring those who have, and are, serving to protect our freedoms.” - Nancy C. -

Statement of William J. “Doc” Schmitz Commander-In-Chief Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States Before the Joint Hear

STATEMENT OF WILLIAM J. “DOC” SCHMITZ COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES BEFORE THE JOINT HEARING COMMITTEES ON VETERANS’ AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE AND UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES WEDNESDAY, MARCH 4, 2020 WASHINGTON, D.C. Chairmen Moran and Takano, Ranking Members Tester and Roe, members of the Senate and House Committees on Veterans’ Affairs, it is my honor to be with you today with representatives of the more than 1.6 million members of the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States (VFW) and its Auxiliary –– America’s largest war veterans organization. I would like to begin by thanking the members of the committees for your willingness to dare to care for our nation’s veterans. During a time of divisive partisanship, you have worked across the aisle and across chambers to pass legislation to improve care and benefits for America’s veterans and our families. As a Vietnam veteran, I am personally thankful for your leadership in passage of the Blue Water Vietnam Veterans Act of 2019. I have many friends, several whom are in the audience today, who would like me to extend their thanks for the long-overdue benefits and recognition. We would equally like to thank you for the bipartisan work to eliminate the Widow’s Tax, which placed undue financial hardship on the survivors of the brave men and women who have made the ultimate sacrifice. With the elimination of the Widow’s Tax, military survivors can focus on healing from the loss of their loved ones and taking care of their families, without a congressionally imposed financial hardship. -

Finding Aid to the Earl L. Butz Papers

FINDING AID TO THE EARL L. BUTZ PAPERS Purdue University Libraries Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center 504 West State Street West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2058 (765) 494-2839 http://www.lib.purdue.edu/spcol © 2016 Purdue University Libraries. All rights reserved. Revised by: Trevor Burrows, Amanda Burdick, Evalyn Stow, and Adriana Harmeyer Processed by: Archives Staff, June 25, 2007 Descriptive Summary Creator Information Butz, Earl L. (1909-2008) Title Earl L. Butz papers Collection Identifier MSF 64 Date Span 1945-2004 Abstract Documents, photographs, letters, scrapbooks, correspondence, biographical material, speeches, artifacts, and subject files documenting Earl L. Butz’s time at Purdue and his career as U.S. Secretary of Agriculture from 1971-1976. Extent 29.06 cf Finding Aid Author Archives Staff Languages English Repository Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center, Purdue University Libraries Administrative Information Location Information: ASC Access Restrictions: The majority of this collection is open for research. Boxes marked “Closed Files” have restricted access. Acquisition The bulk of the collection was donated by Earl L. Butz Information: on June 1, 1978; additional donation from Earl Butz on July 30, 1987. Some artifacts donated by Martha Graham in January 2007. Custodial History: Accession Number: 19780601 Preferred Citation: MSF 64, Earl L. Butz papers, Purdue University Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries 1/24/2020 2 Copyright Notice: Copyright Purdue University Related Materials Marshall A. Martin agricultural oral history interviews, Information: 1993 Purdue Office of Publications Oral History Program collection, 1969-1989 Purdue Archives & Special Collections Oral History Program Collection, 2006-Present 1/24/2020 3 Subjects and Genres Persons Butz, Earl L.