Golden Assembling Ghostly Voices SAM 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conjuring

! New Line Cinema presenta il thriller soprannaturale “The Conjuring - Il caso Enfield”, sequel del grande successo “L’evocazione - The Conjuring”, diretto ancora una volta da James Wan (“Furious 7”), che porta sullo schermo un altro dei casi realmente accaduti su cui hanno indagato i famosi studiosi di demonologia Ed e Lorraine Warren. La candidata all’Oscar Vera Farmiga (“Tra le nuvole”) e Patrick Wilson tornano nel ruolo di Lorraine e Ed Warren che, in una delle loro più terrificanti indagini paranormali, si recano a Londra per aiutare una madre single che vive da sola con quattro bambini in una casa infestata da spiriti malvagi. Il film è il sequel di “L’evocazione - The Conjuring” di Wan, che ha incassato oltre 319 milioni di dollari in tutto il mondo, ed è diventato il secondo film horror di maggior successo di tutti i tempi, piazzandosi subito alle spalle di “L’esorcista”. Nel cast anche Frances O’Connor nel ruolo della madre single, con Madison Wolfe e gli esordienti Lauren Esposito, Patrick McAuley e Benjamin Haigh nel ruolo dei figli; Maria Doyle Kennedy, Simon Delaney, Franka Potente e Simon McBurney. La sceneggiatura è di Chad Hayes & Carey W. Hayes & James Wan e David Leslie Johnson, il soggetto è di Chad Hayes & Carey W. Hayes & James Wan. Peter Safran e Rob Cowan, che avevano già collaborato a “L’evocazione - The Conjuring”, sono i produttori con Wan. I produttori esecutivi sono Toby Emmerich, Richard Brener, Walter Hamada e Dave Neustadter. Nel team anche il direttore della fotografia candidato all’Oscar Don Burgess (“Forrest Gump”, “42”), la scenografa Julie Berghoff, il montatore Kirk Morri, la costumista Kristin Burke e il compositore Joseph Bishara. -

20200913-Bulletin-Wi

September 13, 2020 Twenty-fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time (Proper 19) “Never place a period where God has placed a comma” – Gracie Allen "It's amazing what we lose in life by listening to fear, instead of listening to God." ~ Joyce Meyer "Prayer is first of all listening to God. It's openness. God is always speaking; God's always doing something.” ~ Henri Nouwen (inclusive language used) "God speaks in the silence of the heart. Listening is the beginning of prayer." ~ Mother Teresa "Courage is what it takes to stand up and speak; courage is also what it takes to sit down and listen." ~ Winston Churchill "Every happening, great and small, is a parable whereby God speaks to us, and the art of life is to get the message." ~ Malcolm Muggeridge Order of Worship Prelude: “Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee” by J.S. Bach. Piano, Patty Meyer Greeting Welcome (Fred Breunig) Announcements Presentation of the Stole (Rev. Lise Sparrow) Elisa Angela Lucozzi, You have been called by God and duly chosen by the Guilford Community Church to serve as full time pastor. It is my honor and pleasure to welcome you with the gift of this stole. With it, I remind you of the words of Jesus in Matthew 30: "Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light." I pray that each time you take up this stole to lead worship, you are reminded of God’s still-speaking presence, And that each time you lift it from your shoulders, you take time to glance outside these windows to the beautiful world God has created, And that as you serve this congregation, you meet Christ again and again and again, And live with delight and a song in your heart, that these are your people in easy and not so easy times, bound together always in love and faith. -

Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman's Film Score Bride of Frankenstein

This is a repository copy of Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/118268/ Version: Accepted Version Article: McClelland, C (Cover date: 2014) Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein. Journal of Film Music, 7 (1). pp. 5-19. ISSN 1087-7142 https://doi.org/10.1558/jfm.27224 © Copyright the International Film Music Society, published by Equinox Publishing Ltd 2017, This is an author produced version of a paper published in the Journal of Film Music. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Paper for the Journal of Film Music Of Gods and Monsters: Signification in Franz Waxman’s film score Bride of Frankenstein Universal’s horror classic Bride of Frankenstein (1935) directed by James Whale is iconic not just because of its enduring images and acting, but also because of the high quality of its score by Franz Waxman. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: COMMUNICATING FEAR in FILM

ABSTRACT Title of Document: COMMUNICATING FEAR IN FILM MUSIC: A SOCIOPHOBIC ANALYSIS OF ZOMBIE FILM SOUNDTRACKS Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez Master of Arts, 2014 Directed By: Dr. Patrick Warfield, Musicology The horror film soundtrack is a complex web of narratological, ethnographic, and semiological factors all related to the social tensions intimated by a film. This study examines four major periods in the zombie’s film career—the Voodoo zombie of the 1930s and 1940s, the invasion narratives of the late 1960s, the post-apocalyptic survivalist fantasies of the 1970s and 1980s, and the modern post-9/11 zombie—to track how certain musical sounds and styles are indexed with the content of zombie films. Two main musical threads link the individual films’ characterization of the zombie and the setting: Othering via different types of musical exoticism, and the use of sonic excess to pronounce sociophobic themes. COMMUNICATING FEAR IN FILM MUSIC: A SOCIOPHOBIC ANALYSIS OF ZOMBIE FILM SOUNDTRACKS by Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2014 Advisory Committee: Professor Patrick Warfield, Chair Professor Richard King Professor John Lawrence Witzleben ©Copyright by Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez 2014 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS II INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 1 Introduction 1 Why Zombies? 2 Zombie Taxonomy 6 Literature Review 8 Film Music Scholarship 8 Horror Film Music Scholarship -

Great Listener

HOW TO BE A Great Listener Learn the Art of Listening to Create Intimate Conversation, Trust, and Love How to be a Great Listener Building love and trust involves really listening to our partners, which is not as easy as it sounds. Asking the right questions, empathizing, and making someone feel understood are skills that can dramatically increase intimacy in any relationship. To help you learn how to do this, we recommend that you periodically take your partner’s emotional temperature. You’ll ask, among other things, “How are you doing, baby?” not out of politeness, but because you really want to know. How often is “periodically?” Schedule these times at first, and soon it will come naturally. Try it once a day to start. STEP 1 PREPARE YOURSELF • Shift the focus away from yourself. • Postpone your own agenda for a while. • It’s not about being interesting, it’s about being INTERESTED —genuinely—in the other person. • Tune into your partner’s world. • Hear your partner’s pain, even if you don’t agree with the details. • Try to see your partner’s world from her or his perspective, not your own. Pretend you are doing Mr. Spock’s Vulcan Mind Meld (from Star Trek). 1 STEP 2 ATTUNE That means it’s your job as a listener to be “present” with your partner. Do not minimize your partner’s feelings. When you listen, do not take responsibility for your partner’s feelings. Do not try to make your partner feel better. Do not try to cheer your partner up. -

Cinematic Ghosts: Haunting and Spectrality from Silent Cinema to the Digital Era

Cinematic Ghosts: Haunting and Spectrality from Silent Cinema to the Digital Era. Edited by Murray Leeder. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015 (307 pages). Anton Karl Kozlovic Murray Leeder’s exciting new book sits comfortably alongside The Haunted Screen: Ghosts in Literature & Film (Kovacs), Ghost Images: Cinema of the Afterlife (Ruffles), Dark Places: The Haunted House in Film (Curtis), Popular Ghosts: The Haunted Spaces of Everyday Culture (Blanco and Peeren), The Spectralities Reader: Ghost and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory (Blanco and Peeren), The Ghostly and the Ghosted in Literature and Film: Spectral Identities (Kröger and Anderson), and The Spectral Metaphor: Living Ghosts and the Agency of Invisibility (Peeren) amongst others. Within his Introduction Leeder claims that “[g]hosts have been with cinema since its first days” (4), that “cinematic double exposures, [were] the first conventional strategy for displaying ghosts on screen” (5), and that “[c]inema does not need to depict ghosts to be ghostly and haunted” (3). However, despite the above-listed texts and his own reference list (9–10), Leeder somewhat surprisingly goes on to claim that “this volume marks the first collection of essays specifically about cinematic ghosts” (9), and that the “principal focus here is on films featuring ‘non-figurative ghosts’—that is, ghosts supposed, at least diegetically, to be ‘real’— in contrast to ‘figurative ghosts’” (10). In what follows, his collection of fifteen essays is divided across three main parts chronologically examining the phenomenon. Part One of the book is devoted to the ghosts of precinema and silent cinema. In Chapter One, “Phantom Images and Modern Manifestations: Spirit Photography, Magic Theater, Trick Films, and Photography’s Uncanny”, Tom Gunning links “Freud’s uncanny, the hope to use modern technology to overcoming [sic] death or contact the afterlife, and the technologies and practices that led to cinema” (10). -

The Stress Issue Fearful World

STRESS FRACTURES // A YEAR OF TERROR // PERFECT PEACE // LISTEN TO YOUR FEAR lifechangeTHE STRESS ISSUE FINDING PEACE IN A FEARFUL WORLD AN INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN CULLEN, M.D. Rx FOR WORRY contents THE STRESS ISSUE are you EDITOR// features STRESSED OUT? Daniel Jarvis If you’re like the rest of us, worrying, or who don’t think we can GRAPHIC DESIGNER// Stress Fractures 6 Mallory Nixon you feel pressure every day bear another day at the office, or who – pressure at work, pressure have unspoken fears. This issue of Listen to Your Fear 10 Special thanks to many members and friends at school, pressure at home, LifeChange is all about that good of Weymouth Community Church who have 6 pressure about future decisions, news; a solution for stress and a way contributed time, prayer, money and expertise Rx for Worry 12 to make this issue of LifeChange Magazine and of course, pressure about to win against worry. This solution possible. all those things you should be isn’t inside you; it comes from God Finding Peace 14 Issue 2, “The Stress Issue” doing that you aren’t. and from His Words in the Bible. WHY AM I © 2011 by Weymouth Community Church. All rights reserved. A Year of Terror 18 GETTING Then there’s the twin sister My wife Keri and I decided to lead the LifeChange Magazine is published by of pressure: worry, which our response team for “The Stress Issue” LIFECHANGE? Weymouth Community Church in Medina, Help Desk 20 Ohio as a free gift to our community. The culture has honed to an art of LifeChange because we know what purpose of this publication is to share the life- form. -

Insidious Chapter 2

In Memoriam 1942 – 2013 | ★ ★ ★ ★ ROGEREBERT.COM Choose a Section REVIEWS INSIDIOUS CHAPTER 2 ★ ★ | Simon Abrams September 13, 2013 | ☄ 13 "Insidious: Chapter 2" is a puzzle movie with too many unnecessary pieces and not enough essential ones, but it's superior to its predecessor in a few basic ways. The first sequel to James Wan's "Poltergeist" homage/ripoff features a couple of set pieces that Print Page are thoughtful enough to be scary. This goes a long way in a film where characters constantly explain why and how supernatural Like 21 happenings occur. And unlike its predecessor, this sequel doesn't overuse jump scares and loud noises. For better and worse, 0 screenwriter Leigh Whannell has brought the same klutzy ambition to the "Insidious" films that he did to the first three "Saw" movies (Whannell did not script "Saw"s 4-7, though he did co-write "Chapter Two"'s story with Wan). His ideas for "Insidious: Tweet 6 Chapter 2" are spectacularly misconceived, but they're also the main reason why the movie isn't that bad. "Insidious: Chapter 2" starts where the last film left off. The Lambert family is still haunted. The body of Josh Lambert (Patrick Wilson) is possessed by the spirit of a mysterious bride in black, and his wife Renai (Rose Byrne) doesn't know it—I mean, she should know it, after looking at a ghost-revealing photograph taken by Elise (Lin Shaye), a dead medium, but Renai is presumably not in her right mind after seeing this photo.Elise previously warned Renai that moving is pointless since her son is haunted, not the Lamberts' home, but Renai and not-Josh move back into Josh's childhood home anyway—which is also odd since Renai is told, both in the last film and "Chapter 2," that Josh was also haunted as a child. -

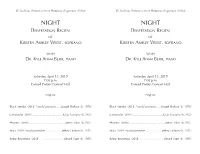

Event Program (PDF)

UC San Diego | Division of Arts & Humanities | Department of Music UC San Diego | Division of Arts & Humanities | Department of Music NIGHT NIGHT DISSERTATION RECITAL DISSERTATION RECITAL OF OF KIRSTEN ASHLEY WIEST, SOPRANO KIRSTEN ASHLEY WIEST, SOPRANO WITH WITH DR. KYLE ADAM BLAIR, PIANO DR. KYLE ADAM BLAIR, PIANO Saturday, April 13, 2019 Saturday, April 13, 2019 7:00 p.m. 7:00 p.m. Conrad Prebys Concert Hall Conrad Prebys Concert Hall Program: Program: Black Sunday (2018) *world premiere.......Joseph Bishara (b. 1970) Black Sunday (2018) *world premiere.......Joseph Bishara (b. 1970) Leinolaulut (2007)........................................Kaija Saariaho (b.1952) Leinolaulut (2007)........................................Kaija Saariaho (b.1952) Phoenix (2016)................................................James Erber (b.1951) Phoenix (2016)................................................James Erber (b.1951) Mara (2019) *world premiere......................Jeffrey Holmes (b. 1971) Mara (2019) *world premiere......................Jeffrey Holmes (b. 1971) Being Beauteous (2018)................................Gérard Pape (b. 1955) Being Beauteous (2018)................................Gérard Pape (b. 1955) NIGHT Dissertation Recital of Kirsten Ashley Wiest, soprano with Dr. Kyle Adam Blair, piano Saturday, April 13, 2019 at 7:00pm Though my soul my set it darkness, it will rise in perfect light; I have loved the stars too fondly to be fearful of the night. Sarah Williams Joseph Bishara (b. 1970) is an American composer, music producer, and actor, best known for his work scoring films such as Insidious, 11-11-11, Dark Skies, and The Conjuring. Bishara's career began with the 1998 Biblical drama Joseph's Gift, though he composes music for mainly horror and thriller films and has collaborated several times with director James Wan. Projects by directors John Carpenter and Joseph Zito, and musicians Ray Manzarek and Diamanda Galás have incorporated Bishara's work. -

Insidious Ebook Free Download

INSIDIOUS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Catherine Coulter | 416 pages | 21 Feb 2017 | POCKET BOOKS | 9781501150302 | English | United States Insidious PDF Book Add the power of Cambridge Dictionary to your website using our free search box widgets. Find a guide to this weekend's new theatrical releases, browse the Q: What does the title mean? Angus Sampson. Ty Simpkins C. From the Editors at Merriam-Webster. Recent Examples on the Web Nothing has worked out, though, and more insidious than the dating itself has been the pressure. Favorite Evil Triumph? Archived from the original on December 20, High blood pressure is an insidious condition which has few symptoms. And the way these protein particles propagate -- getting other proteins to join the pile -- can seem insidious. More Definitions for insidious. Sign up for free and get access to exclusive content:. May 16, Father Martin. Corbett Tuck. Tools to create your own word lists and quizzes. Dangerous and harmful. The man being terrorized lives in Elise's old childhood home, and the threat he's facing is a creature she set free when she was just a child. Keep scrolling for more. Indeed, air conditioning represents one of the most insidious challenges of climate change, and one of the most difficult technological problems to fix. Dalton Lambert. Elise notices something off about Josh and takes a picture of him. It is an insidious system of taxation, which discriminates in favour of the rich. Insidious Writer Dangerous and harmful. I can't sleep either. Leigh Whannell. Log in here. This section does not cite any sources. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Game Sound Technology and Player Interaction: Concepts and Developments

Game Sound Technology and Player Interaction: Concepts and Developments Mark Grimshaw University of Bolton, UK InformatIon scIence reference Hershey • New York Director of Editorial Content: Kristin Klinger Director of Book Publications: Julia Mosemann Acquisitions Editor: Lindsay Johnston Development Editor: Joel Gamon Publishing Assistant: Milan Vracarich Jr. Typesetter: Natalie Pronio Production Editor: Jamie Snavely Cover Design: Lisa Tosheff Published in the United States of America by Information Science Reference (an imprint of IGI Global) 701 E. Chocolate Avenue Hershey PA 17033 Tel: 717-533-8845 Fax: 717-533-8661 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.igi-global.com Copyright © 2011 by IGI Global. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or distributed in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, without written permission from the publisher. Product or company names used in this set are for identification purposes only. Inclusion of the names of the products or com- panies does not indicate a claim of ownership by IGI Global of the trademark or registered trademark. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Game sound technology and player interaction : concepts and development / Mark Grimshaw, editor. p. cm. Summary: "This book researches both how game sound affects a player psychologically, emotionally, and physiologically, and how this relationship itself impacts the design of computer game sound and the development of technology"-- Provided by publisher. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-61692-828-5 (hardcover) -- ISBN 978-1-61692-830-8 (ebook) 1. Computer games--Design. 2. Sound--Psychological aspects.