Living Arrangements Among the Chakhesang Elders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NAGALAND Basic Facts

NAGALAND Basic Facts Nagaland-t2\ Basic Facts _ry20t8 CONTENTS GENERAT INFORMATION: 1. Nagaland Profile 6-7 2. Distribution of Population, Sex Ratio, Density, Literacy Rate 8 3. Altitudes of important towns/peaks 8-9 4. lmportant festivals and time of celebrations 9 5. Governors of Nagaland 10 5. Chief Ministers of Nagaland 10-11 7. Chief Secretaries of Nagaland II-12 8. General Election/President's Rule 12-13 9. AdministrativeHeadquartersinNagaland 13-18 10. f mportant routes with distance 18-24 DEPARTMENTS: 1. Agriculture 25-32 2. Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Services 32-35 3. Art & Culture 35-38 4. Border Afrairs 39-40 5. Cooperation 40-45 6. Department of Under Developed Areas (DUDA) 45-48 7. Economics & Statistics 49-52 8. Electricallnspectorate 52-53 9. Employment, Skill Development & Entrepren€urship 53-59 10. Environment, Forests & Climate Change 59-57 11. Evalua6on 67 t2. Excise & Prohibition 67-70 13. Finance 70-75 a. Taxes b, Treasuries & Accounts c. Nagaland State Lotteries 3 14. Fisheries 75-79 15. Food & Civil Supplies 79-81 16. Geology & Mining 81-85 17. Health & Family Welfare 85-98 18. Higher & Technical Education 98-106 19. Home 106-117 a, Departments under Commissioner, Nagaland. - District Administration - Village Guards Organisation - Civil Administration Works Division (CAWO) b. Civil Defence & Home Guards c. Fire & Emergency Services c. Nagaland State Disaster Management Authority d. Nagaland State Guest Houses. e. Narcotics f. Police g. Printing & Stationery h. Prisons i. Relief & Rehabilitation j. Sainik Welfare & Resettlement 20. Horticulture tl7-120 21. lndustries & Commerce 120-125 22. lnformation & Public Relations 125-127 23. -

1. a Chakhesang Naga Oral Tradition

ASPECTS OF CHAKHESANG FOLKLORE A Critical Study A THESIS Submitted to NAGALAND UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy in English Submitted by ANEILE PURO Ph.D. Regd. No. 512/2012 of 21.08.2012 Under the Supervision of Dr. JANO S. LIEGISE Associate Professor Department of English Nagaland University DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH School of Humanities and Education Nagaland University Kohima Campus, Meriema 2017 ASPECTS OF CHAKHESANG FOLKLORE A CRITICAL STUDY A Thesis Submitted to NAGALAND UNIVERSITY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ENGLISH By ANEILE PURO Ph.D. Regd. No. 512/2012 of 21.08.2012 Under the Supervision of Dr. JANO S. LIEGISE Associate Professor Department of English Nagaland University Department of English Nagaland University Campus: Kohima -797 001 2017 NAGALAND UNIVERSITY (A Central University established by the act of Parliament, 35/1989) Department of English Kohima Campus, Kohima-797001 14th of May 2017 SUPERVISOR’S CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled, Aspects of Chakhesang Folklore: A Critical Study, is a bonafide record of research work done by Ms Aneile Puro, Regn. No.512/2012, Department of English, Nagaland University, Kohima Campus, Meriema during 2012-17. Submitted to the Nagaland University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, this thesis has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma, or other title and the thesis represents independent and original work on the part of the candidate under my supervision. Ms Aneile Puro has completed her research work within the stipulated time. -

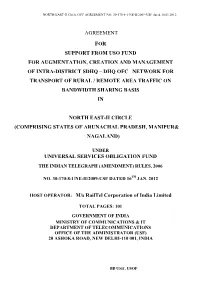

Dhq Ofc Network for Transport of Rural / Remote Area Traffic on Bandwidth Sharing Basis In

NORTH EAST-II Circle OFC AGREEMENT NO. 30-170-8-1-NE-II/2009-USF dated 16.01.2012 AGREEMENT FOR SUPPORT FROM USO FUND FOR AUGMENTATION, CREATION AND MANAGEMENT OF INTRA-DISTRICT SDHQ – DHQ OFC NETWORK FOR TRANSPORT OF RURAL / REMOTE AREA TRAFFIC ON BANDWIDTH SHARING BASIS IN NORTH EAST-II CIRCLE (COMPRISING STATES OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH, MANIPUR& NAGALAND) UNDER UNIVERSAL SERVICES OBLIGATION FUND THE INDIAN TELEGRAPH (AMENDMENT) RULES, 2006 NO. 30-170-8-1/NE-II/2009-USF DATED 16TH JAN, 2012 HOST OPERATOR: M/s RailTel Corporation of India Limited TOTAL PAGES: 101 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIONS & IT DEPARTMENT OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS OFFICE OF THE ADMINISTRATOR (USF) 20 ASHOKA ROAD, NEW DELHI-110 001, INDIA BB UNIT, USOF NORTH EAST-II OFC AGREEMENT No. 30-170-8-1/NE-II/2009-USF dated 16 .01.2012 AGREEMENT FOR SUPPORT FROM USO FUND FOR AUGMENTATION, CREATION AND MANAGEMENT OF INTRA-DISTRICT SDHQ – DHQ OFC NETWORK FOR TRANSPORT OF RURAL / REMOTE AREA TRAFFIC ON BANDWIDTH SHARING BASIS IN NORTH EAST-II CIRCLE(COMPRISING STATES OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH,MANIPUR& NAGALAND This Agreement, for and on behalf of the President of India, is entered into on the 16TH day of January 2012 by and between the Administrator, Universal Service Obligation Fund, Department of Telecommunications, acting through Shri Arun Agarwal, Director (BB) USOF, Department of Telecommunications (DoT), Sanchar Bhawan, 20, Ashoka Road, New Delhi – 110 001 (hereinafter called the Administrator) of the First Party. And M/s RailTel Corporation of India Limited, a company registered under the Companies Act 1956, having its registered office at 10th Floor, Bank of Baroda Building, 16 Sansad Marg New Delhi, acting through Shri Anshul Gupta, Chief General Manager/Marketing, the authorized signatory (hereinafter called the Host Operator which expression shall, unless repugnant to the context, includes its successor in business, administrators, liquidators and assigns or legal representatives) of the Second Party. -

Directory Establishment

DIRECTORY ESTABLISHMENT SECTOR :RURAL STATE : NAGALAND DISTRICT : Dimapur Year of start of Employment Sl No Name of Establishment Address / Telephone / Fax / E-mail Operation Class (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) NIC 2004 : 0121-Farming of cattle, sheep, goats, horses, asses, mules and hinnies; dairy farming [includes stud farming and the provision of feed lot services for such animals] 1 STATE CATTLE BREEDING FARM MEDZIPHEMA TOWN DISTRICT DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797106, STD CODE: 03862, 1965 10 - 50 TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 0122-Other animal farming; production of animal products n.e.c. 2 STATE CHICK REPARING CENTRE MEDZIPHEMA TOWN DISTRICT DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797106, STD CODE: 03862, TEL 1965 10 - 50 NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 3610-Manufacture of furniture 3 MS MACHANIDED WOODEN FURNITURE DELAI ROAD NEW INDUSTRIAL ESTATE DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD 1998 10 - 50 UNIT CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. 4 FURNITURE HOUSE LEMSENBA AO VILLAGE KASHIRAM AO SECTOR DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: 2002 10 - 50 NA , TEL NO: 332936, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 5220-Retail sale of food, beverages and tobacco in specialized stores 5 VEGETABLE SHED PIPHEMA STATION DISTT. DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: NA , TEL NO: NA 10 - 50 NA , FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. NIC 2004 : 5239-Other retail sale in specialized stores 6 NAGALAND PLASTIC PRODUCT INDUSTRIAL ESTATE OLD COMPLEX DIMAPUR NAGALAND PIN CODE: 797112, STD CODE: NA , 1983 10 - 50 TEL NO: 226195, FAX NO: NA, E-MAIL : N.A. -

Power Sector Reform and Restructuring in Nagaland

Power Sector Reform and Restructuring in Nagaland International Management Institute B-10, Qutab Institutional Area Tara Crescent, New Delhi – 110 016 Power Sector Reform and Restructuring in Nagaland Final Report March 2006 International Management Institute B-10, Qutab Institutional Area Tara Crescent, New Delhi – 110 016 CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................................................................... i SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS.......................................................................................................................... iv 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 The Present Study................................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Organisation of the Study ...................................................................................................................... 3 2. THE STATE OF NAGALAND....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Socio-Economic Background............................................................................................................... -

Festivals of the Chakhesangs of Nagaland

www.ijcrt.org © 2020 IJCRT | Volume 8, Issue 10 October 2020 | ISSN: 2320-2882 Festivals of the Chakhesangs of Nagaland Dr. Akhil Kumar Gogoi Abstract: Chakhesangs are a prominent tribe of Nagaland. The Phek district of Nagaland is known as the home of the Chakhesang community. The word Chakhesang is an amalgamation of the names of three tribes, ‘Cha’ from Chokri, ‘Khe’ from ‘Khezha’ and ‘Sang’ from Sangtam. Throughout the year, they engage in different festivals celebrated at different times. Their festivals, various activities and rituals are mostly related to the agricultural sphere. All the people of the tribe, rich and poor, men and women engage in these festivals. Boys and girls celebrate by dancing and singing together. This paper studies the various festivals and rituals prevalent among the people of the Chakhesang tribe. Keywords: Festival, Chakhesang, Agriculture. Introduction : Different tribes have different timings for different festivals owing to climatic conditions. Yet the motives and the modes of the festivals are basically same for all the Naga Communities. It is agricultural activities around which most of the festivals are woven as it is the main occupation of the Chakhesang Nagas. There are two different systems of cultivation. They are, (i) shifting and (ii) terraced cultivation. Objectives of the Study : The present study is an attempt to understand the different festivals and their timings of celebration amongest Chakhesang community. This paper also focuses how they involve in cultivation or agriculture through the different festivals in different seasons. The present study helps to understand the various activities, various rituals and food and sanctification done by the Chakhesang men and women during the festivities. -

National Rural Health Mission State Programme Implementation Plan

GOVERNMENT OF NAGALAND NATIONAL RURAL HEALTH MISSION STATE PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION PLAN 2009-10 Draft v.1 February 2009 Submitted by State health Society National Rural Health mission Government of Nagaland TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER CONTENT PAGE - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 BACKGROUND 2 PROCESS OF PLAN PREPARATION 3 SITUATION ANALYSIS OF THE DISTRICT 3.1 BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS 3.2 PUBLIC HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE 3.3 HUMAN RESOURCES IN THE STATE 3.4 FUNCTIONALITY OF THE HEALTH FACILITIES 3.5 STATUS OF LOGISTICS 3.6 STATUS OF TRAINING INFRASTRUCTURE 3.7 BCC INFRASTRUCTURE 3.8 PRIVATE AND NGO HEALTH SERVICES/ INFRASTRUCTURE 3.9 ICDS PROGRAMME 3.10 ELECTED REPRESENTATIVE OF PRIS 3.11 NGOS AND CBOS 3.12 KEY HEALTH INDICATORS (MH,CH AND FP) 3.13 NATIONAL DISEASE CONTROL PROGRAMMES 3.14 LOCALLY ENDEMIC DISEASES IN THE STATE 3.15 NEW INTERVENTIONS UNDER NRHM 3.16 CRITICAL ANALYSIS & REQUIREMENTS 4 PROGRESS AND LESSONS LEARNT FROM NRHM IMPLEMENTATION DURING 08-09 5 CURRENT STATUS AND GOAL 6 GOAL, OBJECTIVES, STRATEGIES, AND ACTIVITIES UNDER DIFFERENT COMPONENTS OF NRHM 6.1 PART A RCH PROGRAMME 6.2 PART B NRHM ADDITIONALITIES 6.3 PART C UNIVERSAL IMMUNIZATION PROGRAMME 6.4 PART D NATIONAL DISEASE CONTROL PROGRAMME 6.5 PART E INTERSECTORAL CONVERGENCE 6.6 PART F OTHER NEW PROGRAMMES 7 MONITORING AND EVALUATION/ HMIS 8 WORK PLAN 8.1 PART A RCH PROGRAMME WORKPLAN 8.2 PART B NRHM ADDITIONALITIES WORKPLAN 9 BUDGET 9.1 PART A RCH PROGRAMME 9.2 PART B NRHM ADDITIONALITIES 9.3 PART C UNIVERSAL IMMUNIZATION PROGRAMME 9.4 PART D NATIONAL DISEASE CONTROL PROGRAMME 9.5 PART E INTERSECTORAL CONVERGENCE 9.6 PART F OTHER NEW PROGRAMMES - ABBREVIATION - ANNEXURES 1 FORMAT FOR SELF ASSESSMENT OF STATE PIP AGAINST APPRAISAL CRITERIA (ANNEX 3 A OF RCH OPERATING MANUAL) 2 ACHIEVEMENT IN TERMS OF RCH PROGRAMME IN NAGALAND STATE PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION PLAN 2009-10 NAGALAND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in Nagaland was launched in Feb‘06. -

CHAKHESANG WRESTLER the Motif Above Represents One of the Most Popular Games Among the ‘Chakhesang Naga’- Wrestling

CHAKHESANG WRESTLER The motif above represents one of the most popular games among the ‘Chakhesang Naga’- Wrestling. It is a game played by the men folk and loved by all. It is a simple but highly technical sport and is played by tying a waist band (belt), usually made of cotton cloth. The wrestlers generally maintain special diet and proper exercises to make themselves fit for the prestigious annual tournament. The individual winner is held in high esteem and occupies a respectable position in the community. Pages Foreword 1 Preface 4 Acknowledgements 5 History and scope of the District Census Hand Book 6 Brief history of the district 8 Analytical note i. Physical features of the district 10 ii. Census concepts iii. Non-Census concepts iv. 2011 Census findings v. Brief analysis of PCA data based on inset tables 1-35 vi. Brief analysis of the Village Directory and Town Directory data based on inset tables 36-45 vii. Major social and cultural events viii. Brief description of places of religious importance, places of tourist interest etc ix. Major characteristics of the district x. Scope of Village and Town Directory-column heading wise explanation Section I Village Directory i. List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at census 2011 62 ii. Alphabetical list of villages along with location code 2001 and 2011 63 iii. RD Block Wise Village Directory in prescribed format 68 Appendices to village Directory 114 Appendix-I: Summary showing total number of villages having Educational, Medical and other amenities-RD Block level Appendix-IA: -

Minutes of the 17Th Meeting of Expert Committee Held on 29.09.2017

L, . T\. t, & No. 14-912015-M.l Government of lndia Ministry of Culture Shastri Bhawan, New Delhi Dated: 29th September, 2017 .OFFICE MEMORANDUM Sub: MinutEh-of-ihe LTth meeting of the Expert Committee held on 29.O9.2017 under the "Museurn Grant Scheme" held on 37:08.2017 for the year 2OL7-2018' The unciijisigned is ciirected to enclose herewith a copy of the minutes of the 17th M--eting of the Expert Llommittee under the "Museum Grant Scheme" held on 31.08.2017 t;,inidiei the Cl'rairi-nanship of Additional Secretary, Ministry of Culture to consider the.p-1-.o,Br2sais under tt-,e fviuseum Grant Scl'reme for the year 2017-18. -1':<i'1fi- (5. K. Singh) i+i:]*:..--: Under Secretary to the Govt. of lndia _ :.: --_ IO, ,l-. ,-- . All Members of the Committee (as per list) Copy for information to:- Mnt. PS to HCM r'. nno \j\2.'-'/. Wtosecretaryl*5€r'Io )ecrelary ILultute,(culture) 3.J' PPSJ to!v Additionalsecretary (culture) '| '! ' Kbfl\) u ' :'-'' \' 4. PPS to Joint Secretary (Museums)- AI I 5. P! to Deputy Secretary (Museums .Lol'l- ') 9\ Ministrv of Culture Minutes of the 17th meeting of Expert Gommittee on Museum Grant Scheme held on 31.08.2017 The l Tthmeeting of the Expert Committee to consider applications received in the Minisky under the 'Museum Grant Scheme' was held on 31.08.2017 under the Chairmanship of Ms.Sujata Prasad, Addl. Secretary, Ministry of Culture. List of participants is enclosed at Annexure-1. 2. The agenda items on the proposals received for financial assistance under Museum Grant Scherne vsere taken up for discussion as given below. -

Nagaland May 2021 OHOT

Nagaland (7 Days, 6 Nights) Tour Route: Kohima – Jakhama – Dzokou – Khonoma- Kohima Tour Duration: 6 Nights Travel Dates: Oct 10-16 Group Size: 18 people BRIEF ITINERARY: Oct 10: Arrive at Dimapur Airport. Transfer to Kohima. O/N Kohima hotel Oct 11: Head to Khonoma Heritage village, explore Morung and then head to Jakhama campsite. O/N Jakhama camp Oct 12: Drive to trek starting point and trek to the stunning Dzokou Valley. O/N Dzukou camp Oct 13: Explore Dzokou Valley. O/N Dzukou camp Oct 14: Trek down and drive to Kohima City. O/N Kohima hotel Oct 15: Drive to Khezhakeno (Oldest Naga Village). Observe the local life and visit Cheda Lake. O/N Kohima hotel Oct 16: Drive to Dimapur airport. Fly home DETAILED ITINERARY: Oct 10: Arrive at Dimapur Airport. Transfer to Kohima. O/N Kohima hotel Upon your arrival at Dimapur airport, a cab will transfer the group to the capital of Nagaland, Kohima. It is a 70 km journey, and will take about three hours to cover. The property we have chosen for this night is a place we love. It doesn’t feel like a hotel, more like a home, but there is so much culture and history within those very walls and we shall share the stories once we take you there. They have a cute garden, the gentlest puppy in the world, and a lot of Naga artefacts, weapons and books in the various rooms. They also prepare some delicious meals that will leave you wanting more. And, of course, you must try Naga food also. -

183 Appendix 1.1.1 Budget Vis-À-Vis Expenditure of Departments Under

Appendix 1.1.1 Budget vis-à-vis expenditure of departments under Social Sector during 2017-18 (Paragraph reference: 1.1) (``` in crore) Sl. No Name of the Departments Total Budget Expenditure 1 School Education 1496.39 1282.94 2 Technical Education 26.11 22.06 3 Higher Education 198.61 157.97 4 SCERT 41.04 35.03 5 Youth Resources and Sports 68.50 60.16 6 Art and Culture 26.68 23.03 7 Health and Family Welfare 683.80 614.09 8 Water Supply and Sanitation 316.22 213.39 9 Urban Development 112.08 89.44 10 Municipal Affairs 197.18 152.42 11 Information and Public Relations 36.67 35.76 12 Labour 11.21 10.66 13 Employment and Training 30.84 27.89 14 Social Welfare 289.18 225.38 15 Women Welfare 14.59 11.64 Total 3549.10 2961.86 Source: Appropriation Accounts. Appendix 1.3.1 List of Government Higher Secondary Schools/ Government Secondary Schools inspected by Audit team (Paragraph reference: 1.3.14.1) Sl. No. Name of School District Government Higher Secondary Schools (GHSS) 1 Government Higher Secondary School, Jotsoma Kohima 2 Government Higher Secondary School, Tseminyu Kohima 3 Government Higher Secondary School, Ruzukhrie Kohima 4 TM Government Higher Secondary School Kohima 5 Government Higher Secondary School, Chiechama Kohima 6 John Government Higher Secondary School, Viswema Kohima 7 Government Higher Secondary School, Seikhazou Kohima 8 Government Higher Secondary School, Mangkolemba Mokokchung 9 Government Higher Secondary School, Ungma Mokokchung 10 Mayangnokcha Government Higher Secondary School Mokokchung 11 Government Higher Secondary School, Tuli Mokokchung 12 N.I Jamir Government Higher Secondary School Mokokchung 13 Government Higher Secondary School, Longkhim Tuensang 183 Audit Report for the year ended 31 March 2018 Sl. -

NAGALAND (KOHIMA – 120 PAX) Day – 1 (20.12.2014, Saturday

NAGALAND (KOHIMA – 120 PAX) Day – 1 (20.12.2014, Saturday) : ARRIVE AT GUWAHATI RAILWAY STATION – KOHIMA (12Hrs.) Meet and greet on arrival at Guwahati Railway Station at 1700 hrs. Proceed at night towards Kohima reach Kohima at around 0800hrs on 21.12.2014. Day –2 (21.12.2014, Sunday) : KOHIMA - KHONOMA - KOHIMA (20 KMS / 1 HR) After check-in and after breakfast, explore Kohima and its surroundings. Visit local market where you will find all kinds of worms and insects being sold at the market by the local people. Visit Second World War cemetery where thousands lie there remembered. Further drive to Kisama, the heritage village where the annual Hornbill festival takes place. Visit different morungs of the Nagas and the war Museum. Lunch enroute/hotel. Next visit Kigwema village and Jakhama village to see rich men houses, morungs, etc. Drive back to Kohima, Visit State Museum. Diner and overnight at Kohima Hotel. History & Tradition Day – 3 (22.12.2014, Monday): KOHIMA After breakfast drive to the legendary village Khonoma. Visit Grover’s memorial at Jotsoma village. On reaching Khonoma, explore the village. Khonoma became the first Green Village in India when the village community decided to stop hunting, logging and forest fire. Khonoma was also known for her valor and prowess in those days of war. At Khonoma visit G. H. Damant Memorial, the first British political officer to the Naga hills, visit morungs, cairn circles, age group houses, ceremonial gates, etc. Drive to the buffer zone of Khonoma Nature Conservation and Tragopan Sanctuary. PICNIC LUNCH!! See the state animal Mithun (Bos Frontalis) and feed them with salt.