Universal Periodic Review Bangladesh: Stakeholder’S Submission Under the 3Rd Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daily Star Weekend Magazine (SWM) in February 9, 2007

Interview Freethinkers of Our Time For over the last one and a half decades Mukto-Mona has been fighting for the development of humanism and freethinking in South Asia. The organisation's member-contributor's included novelist Humayun Azad. In an email conversation with the SWM, three members of mukto-mona.com talk about the state of freedom in Bangladesh, and South Asia in general. Ahmede Hussain 1. How has Mukto-Mona evolved? Can you please explain the idea behind Mukto-Mona for our readers? Avijit Roy: Mukto-Mona came into being in the year 2000, with the intention of debating and promoting critical issues that are of the utmost importance in building a progressive, rational and secular society, but usually are ignored in the man stream Bangladeshi and South Asian media. For example, consider the question: Does one need to adhere to a religious doctrine to live an honest, decent and fulfilled life? This may seem like an off-the-track topic to many, but at the same, we cannot deny that this is a very critical and crucial question. It was 2000. I was very active on the net and writing in several e-forums simultaneously on topics pertaining to rationalism, humanism and science. One such e-forum which I came across at that time was News From Bangladesh (NFB) which regularly published debates between believers and rationalists like me. Although only a handful in number, I discovered, I was not alone. I met a few more expatriate Bangladeshi writers (of whom some constitute today Mukto-Mona’s advisory and editorial board) who also thought in same way about religious doctrine and conventional beliefs. -

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Updated October 17, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44094 Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world’s eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. -

Political and Legal Status of Apostates in Islam

Political and Legal Status of Apostates in Islam The Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain was formed in June 2007 in order to break the taboo that comes with renouncing Islam. The main aims of the organisation are to provide support to and highlight the plight of ex- Muslims, challenge Sharia and apostasy laws and take a stand for reason, universal rights and secularism. Atheist Alliance International is a global alliance of atheist and freethought groups and individuals, committed to educating its members and the public about atheism, secularism and related issues. Atheist Alliance International is proud to support its Affiliate, the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain, in the publication of this report. For further information contact: CEMB BM Box 1919 London WC1N 3XX, UK Tel: +44 (0) 7719166731 [email protected] www.ex-muslim.org.uk Atheist Alliance International [email protected] www.atheistalliance.org Published by Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain, December 2013 © Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain 2013 – All rights reserved ISBN: 978-0-9926038-0-9 Political and Legal Status of Apostates in Islam A Publication of the Council of Ex-Muslims of Britain Political and Legal Status of Apostates in Islam Died Standing A severed head in between your hands my eyes on the broken clock And sad and rebellious poems and the wolf, unafraid of the gun On my doubts of the origin of existence, on choking loneliness when drunk And longing and inhaling you, and the depth of the tragedy not seeing you The artery destined to blockage, and your -

The Virus of Faith Avijit Roy

And so too may the institutionalized rious reasons, as discharged through Anyway, that’s the music he stepped to piety of even modern science precipi- American (irrational) contrarianism, a century and a half ago, and so still do tate revolt—because, for better or for portend not simply recidivistic cultural a lot of Americans today. worse, revolt invigorates. decay but (and without gilding them If all this sounds like so much fuzzy, with any facile romantic or Neitzschean sociological impressionism, well, maybe virtue) some as yet unrecognized (and Steven Doloff is professor of humanities it is. But might there not also be, lurk- even) evolutionary function. and media studies at the Pratt Institute. ing amidst the fuzz, just a grain of (not Ralph Waldo Emerson once said of His writings on culture and education have strictly scientific) truth as well, about the perpetual fluidity of human con- appeared in the New York Times, the a peculiar American-exceptionalist sciousness that every thought was a Washington Post, the Chronicle of Higher gestalt? “The heart has its reasons,” “prison” and that a heartfelt, open- Education, and FREE INQUIRY. claimed Pascal, “of which reason knows ended guess was somehow more grati- nothing.” And perhaps those myste- fying than a logically constraining fact. Global Humanism The Virus of Faith Avijit Roy Religion, a medieval form of unreason, recent experiences in this regard verify extremist by the name of Farabi Shafiur when combined with modern weaponry the horrific reality that such religious Rahman openly issued death threats becomes a real threat to our freedoms. extremism is a “virus of faith.” to me through his numerous Facebook —Salman Rushdie It all started with a book. -

Testimony of Rafida Bonya Ahmed, Humanist Activist and Author On

Testimony of Rafida Bonya Ahmed, Humanist Activist and Author On behalf of the American Humanist Association Before the United States House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations and Oversight and Reform Committee Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties Joint Hearing on “Ending Global Religious Persecution” January 28, 2020 Washington, District of Columbia 1 Chairman Raskin, Ranking Member Roy, Members of the Oversight and Reform Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, Chairwoman Bass, Ranking Member Smith, and Members of the Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights and International Organizations, thank you for this opportunity to testify on behalf of the American Humanist Association concerning the harm caused by the numerous prohibitions against blasphemy that exist around the world. My name is Rafida Bonya Ahmed. I am a Bangladeshi-American author and blogger. I am a humanist and atheist. I am a mother to a recent John’s Hopkins graduate. I am a U.S. citizen and a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics Human Rights Centre. And I am here today to provide a much-needed voice for the nonreligious communities and individuals harmed by religious persecution. While I would not venture to represent the interests of all nonreligious people, I am a person who knows first-hand the violence accusations of blasphemy can incite. I appreciate that the committees are putting an overdue spotlight on the egregious violations of human rights conducted in the name of religion, and I urge both committees and Congress to pursue policies that hold bad actors to account. -

Sadf Comment

COMMENT SADF COMMENT March 2015 Volume 2 The Killing of Avijit Roy: Silencing free-thinking and progressive conscience in Bangladesh Siegfried O. Wolf March, 2015 South Asia Democratic Forum (SADF) Avenue des Arts – 1210 Brussels, Belgium www.sadf.eu COMMENT ABOUT SADF COMMENTS The SADF Comment series seeks to contribute innovative and provocative thinking on significant, on-going debates as well as provide immediate, brief analysis and opinion on current occurrences and developments in South Asia. The topics covered are not only directed towards academic experts in South Asian affairs but are also of relevance for professionals across disciplines with a practical interest in region. Therefore, the SADF Comment series serves as a platform for commentators who seek an international audience for opinions that impact state and society in South Asia and beyond. ABOUT SADF South Asia Democratic Forum (SADF) is a non-partisan, autonomous think tank dedicated to objective research on all aspects of democracy, human rights, security, and intelligent energy among other contemporary issues in South Asia. SADF is based in Brussels and works in close partnership with the Department of Political Science at South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University. COMMENT On February 26 the blogger Avijit Roy, a US-citizen of Bangladeshi origin, published author, and prominent voice against religious intolerance was murdered publicly in Dhaka after returning from a book fair (cf. TheGuardian, 27.2.2015; cf. Alam, 27.2.2015). Roy, an engineer by profession was not only known as a passionate writer but also as the founder of the Bengali- language blog Mukto-Mona, the “Free Mind”. -

The Situation of Freethinkers in Bangladesh

September 2015 The situation of freethinkers in Bangladesh Briefing note By the European Humanist Federation FOCUS ON BANGLADESH iolations of the right to freedom of religion or belief and freedom of speech have dramatically increased over the past few years in Bangladesh. This year, four V secular and humanist bloggers were hacked to death by islamist groups for “insulting Islam”. Niladri Chatterjee (Niloy Neel), Ananta Bijoy Das, Md Washiqur Rahman Babu and Avijit Roy were murdered on respectively 7 August, 12 May, 30 March and 27 February 2015. These four murders follow a succession of attacks and “blasphemy”-type prosecutions over several years against those who identify as non-religious or humanist, or those who seek to criticize political Islam in Bangladesh. For instance: Prof. Shafiul Islam was murdered on 25 November 2014. On 31 March 2014, teenaged bloggers Kazi Mahbubur Rahman Raihan and Ullash Das were sent to jail for Facebook comments supposedly “insulting” Islam and the Prophet. This was only after they had been attacked and beaten by a mob. In 15 February 2013, blogger, architect and activist Ahmed Rajeeb Haider was hacked to death. Asif Mahiuddin was stabbed in January 2013 and survived that attack, only to be arrested on 3 April of the same year and charged with “offending Islam and its Prophet”. Subrata Adhikari Shuvo, Mashiur Rahman Biplob, and Rasel Parvez were also arrested for “hurting religious sentiments” in 2013. Writer Taslima Nasrin (Sakharov Prize 1994) was forced to leave Bangladesh to escape arrest and death. These writers were attacked and murdered because they were proponents of secularism and humanism, voiced skeptical and rationalist arguments and called for justice and freedom. -

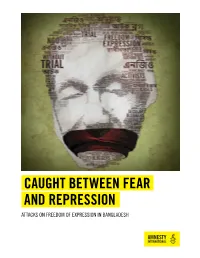

Caught Between Fear and Repression

CAUGHT BETWEEN FEAR AND REPRESSION ATTACKS ON FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION IN BANGLADESH Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Cover design and illustration: © Colin Foo Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street, London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 13/6114/2017 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION TIMELINE 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & METHODOLOGY 6 1. ACTIVISTS LIVING IN FEAR WITHOUT PROTECTION 13 2. A MEDIA UNDER SIEGE 27 3. BANGLADESH’S OBLIGATIONS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW 42 4. BANGLADESH’S LEGAL FRAMEWORK 44 5. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 57 Glossary AQIS - al-Qa’ida in the Indian Subcontinent -

Kalmer, I. Early Orientalism: Imagined Islam and the Notion of Sublime Power

Journal of International and Global Studies Volume 7 Number 1 Article 13 11-1-2015 Kalmer, I. Early Orientalism: Imagined Islam and the Notion of Sublime Power. New York: Routledge, 2012. Asif Mohiuddin S.H Institute of Islamic Studies, University of Kashmir, Srinagar, India., [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/jigs Part of the Anthropology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Mohiuddin, Asif (2015) "Kalmer, I. Early Orientalism: Imagined Islam and the Notion of Sublime Power. New York: Routledge, 2012.," Journal of International and Global Studies: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 13. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/jigs/vol7/iss1/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International and Global Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kalmer, I. Early Orientalism: Imagined Islam and the Notion of Sublime Power. New York: Routledge, 2012. In recent decades, the growing political influence of Islam throughout the Muslim world has revealed an unmediated nexus between religious ideals and the ensuing political realities. In this work, Ivan Kalmer presents an in-depth analysis of the relationship between divine power and existential realities encompassing human self and the universe. Kalmer refutes the idea that Islam promotes an authoritarian form of government and demonstrates that the presumption that it does so emanates from deep reaching anxieties that go beyond religion and even the East-West relationship. -

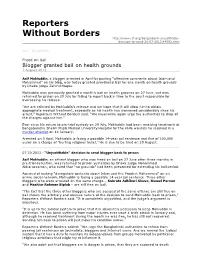

Reporters Without Borders Decision-To-Send-30-07-2013,44992.Html

Reporters Without Borders http://www.rsf.org/bangladesh-unjustifiable- decision-to-send-30-07-2013,44992.html Asia - Bangladesh Freed on bail Blogger granted bail on health grounds 7 August 2013 Asif Mohiuddin, a blogger arrested in April for posting “offensive comments about Islam and Mohammed” on his blog, was today granted provisional bail for one month on health grounds by Dhaka judge Zahirul Haque. Mohiuddin was previously granted a month’s bail on health grounds on 27 June, but was returned for prison on 29 July for failing to report back in time to the court responsible for overseeing his release. “We are relieved by Mohiuddin’s release and we hope that it will allow him to obtain appropriate medical treatment, especially as his health has worsened considerably since his arrest,” Reporters Without Borders said. “We meanwhile again urge the authorities to drop all the charges against him.” Ever since his return to pre-trial custody on 29 July, Mohiuddin had been receiving treatment at Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University Hospital for the knife wounds he received in a murder attempt on 14 January. Arrested on 3 April, Mohiuddin is facing a possible 14-year jail sentence and fine of 100,000 euros on a charge of “hurting religious belief.” He is due to be tried on 25 August. 07.30.2013 : “Unjustifiable” decision to send blogger back to prison Asif Mohiuddin, an atheist blogger who was freed on bail on 27 June after three months in pre-trial detention, was returned to prison yesterday by Dhaka judge Mohammad Akharuzzaman, who ruled that “no grounds” had been presented for extending his bail period. -

Profiles of Islamist Militants in Bangladesh by Shafi Md Mostofa and Natalie J

PERSPECTIVES ON TERRORISM Volume 13, Issue 5 Profiles of Islamist Militants in Bangladesh by Shafi Md Mostofa and Natalie J. Doyle Abstract Since the early 1980s, Bangladeshi militants have joined wars in Libya, Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria to fight for what they defined as the Ummah. Foreign cases of perceived Muslim suffering have always played a significant role in the escalation of Islamist militancy in Bangladesh. Originally, violent Islamists emerged principally in the Madrassas and came from poor families with rural backgrounds. The recent wave of Islamist militancy associated with the arrival in 2013 of Al Qaeda and the Islamic State has dramatically altered the character of Islamist militancy. Online radicalization is playing a much larger role and militant organizations are increasingly recruiting urban youths attending secular educational institutions, from both the upper and the middle classes. This Research Note explores the new profile of Islamist militants in Bangladesh by examining the biographies of the deceased Islamist militants who were killed by security forces in different operations and gunfights during the period between June 2016 and December 2018. The authors use data acquired from three newspapers renowned for covering Islamist militancy issues as well as information provided by Bangladeshi security forces. Data have been limited to deceased militants because their militancy was proven by their violent actions, at least in a number of cases. Keywords: Bangladesh, Islamist, Militant, Radicalization, and Terrorism Introduction The problem of Islamist militancy in Bangladesh first came to the public’s attention in the early 1980s and its rise has been inextricably linked with global phenomena. -

I. International Crimes Tribunal Protests and Related Violence

H U M A N R I G H T S BLOOD ON THE STREETS The Use of Excessive Force during Bangladesh Protests WATCH Blood on the Streets The Use of Excessive Force During Bangladesh Protests Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-30404 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org AUGUST 2013 978-1-6231-30404 Blood on the Streets The Use of Excessive Force During Bangladesh Protests Map of Bangladesh ...................................................................................................................... i Summary ...................................................................................................................................