Middle Years Teacher Credentialing in Aotearoa/New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Word from the Principal Mangere

Mangere College Term 3 Newsletter 2017 A word from the Principal It was great to see so many whanau at the recent PST’s. We always have very high numbers of families at these events and it is very positive to see all of the conversations happening. Many of our students are well on track to achieve our goal this year of 14+ credits for every student in every course and we are putting in place ways to help those students who are not on track. One of the biggest factors that help students to achieve is the support they receive from home. We really appreciate the effort that you make to support your child and we know it can make a big difference. Here are some things that you can do at home: · Ask your child how they are doing at school · Keep up to date with the number of credits they have and what is coming up · Talk to them after each exam or assessment about how it went · Support them when they have important exams and assessments The KAMAR app is very useful to stay up-to-date with how your child is going at school. If you did not receive a letter about the app at your PST then please contact the school. Tom Webb Principal of Mangere College Inside this issue: Welcome to new Staff.....................................................p2 NCEA Update/Library......................................................p3 Physical Education...........................................................p4 The Wholehearted/Wood Technology...................p5 Spirit of Adventure...........................................................p6/7 Shadow Tech -

Title Page Head

Conceptions of Assessment and Feedback Elizabeth Peterson and Earl Irving 2007 Conceptions of Assessment and Feedback Elizabeth Peterson and Earl Irving Faculty of Education, The University of Auckland 2007 Researchers, University of Auckland Dr Gavin Brown Mrs Helen Dixon Dr Mavis Haigh Dr S. Earl Irving (Principal Investigator) Dr Elizabeth Peterson (Principal Investigator) Teacher-researchers James Bashford, Pakuranga College Catherine Hellyer, Pakuranga College Amanda McKay, Waitakere College/Henderson High School Harold Merriman, Papatoetoe High School Darryn Rae, Papatoetoe High School Rebecca Sharkey, Waitakere College Reports from Auckland UniServices Limited should only be used for the purposes for which they were commissioned. If it is proposed to use a report prepared by Auckland UniServices Limited for a different purpose or in a different context from that intended at the time of commissioning the work, then UniServices should be consulted to verify whether the report is being correctly interpreted. In particular it is requested that, where quoted, conclusions given in UniServices reports should be stated in full. Teaching and Learning Research Initiative P O Box 3237 Wellington New Zealand www.tlri.org.nz © Crown, 2007 Acknowledgements The Conceptions of Assessment and Feedback (CAF) research team would like to thank the Teaching and Learning Research Initiative (TLRI) for their funding and support of this project and the New Zealand Council for Educational Research which administers the TLRI. We have had a great deal of encouragement from both Christina Smits and Rosemary Hipkins. We would also like to thank NZCER/TLRI for the additional funding we received in support of two of our teacher-researchers who presented their CAF work at conferences. -

Schools Advisors Territories

SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews Northland Gaynor Matthews Auckland Gaynor Matthews Coromandel Gaynor Matthews Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Waikato Angela Spice-Ridley Bay of Plenty Angela Spice-Ridley Gisborne Angela Spice-Ridley Central Plateau Angela Spice-Ridley Taranaki Angela Spice-Ridley Hawke’s Bay Angela Spice-Ridley Wanganui, Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Manawatu, Horowhenua Sonia Tiatia Welington, Kapiti, Wairarapa Sonia Tiatia Nelson / Marlborough Sonia Tiatia West Coast Sonia Tiatia Canterbury / Northern and Southern Sonia Tiatia Otago Sonia Tiatia Southland SCHOOLS ADVISORS TERRITORIES Gaynor Matthews NORTHLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION AUCKLAND REGION CONTINUED Bay of Islands College Albany Senior High School St Mary’s College Bream Bay College Alfriston College St Pauls College Broadwood Area School Aorere College St Peters College Dargaville High School Auckland Girls’ Grammar Takapuna College Excellere College Auckland Seven Day Adventist Tamaki College Huanui College Avondale College Tangaroa College Kaitaia College Baradene College TKKM o Hoani Waititi Kamo High School Birkenhead College Tuakau College Kerikeri High School Botany Downs Secondary School Waiheke High School Mahurangi College Dilworth School Waitakere College Northland College Diocesan School for Girls Waiuku College Okaihau College Edgewater College Wentworth College Opononi Area School Epsom Girls’ Grammar Wesley College Otamatea High School Glendowie College Western Springs College Pompallier College Glenfield College Westlake Boys’ High -

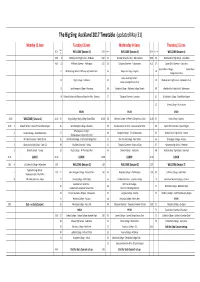

The Big Sing Auckland 2017 Timetable (Updated May

The Big Sing Auckland 2017 Timetable (updated May 31) Monday 12 June Tuesday 13 June Wednesday 14 June Thursday 15 June Choir Choir No Choir No 8.50 No WELCOME (Session 2) 8.50 WELCOME (Session 4) 8.50 WELCOME (Session 6) 9.00 9 Westlake Girls' High School ‐ En Masse 9.00 32 Diocesan School for Girls ‐ Bella Cantoris 9.00 . 56 Westlake Girls' High School ‐ Nota Bella 9.15 10 Mt Albert Grammar ‐ Ad Augusta 9.15 33 Takapuna Grammar ‐ Takacrooners 9.15 57 Epsom Girls' Grammar ‐ Canto Vivo Sancta Maria College ‐ Sancta Maria 11 McAuley High School ‐ McAuley High School Choir 34 Rangitoto College ‐ Singlets 58 College Senior Choir James Cook High School ‐ 12 King's College ‐ VoKCalise 35 59 Westlake Girls' High School ‐ Choralation Choir James Cook High School Choir 13 Saint Kentigern College ‐ Menasing 36 Macleans College ‐ Macleans College Chorale 60 Westlake Boys' High School ‐ Momentum 14 Dilworth School and Diocesan School for Girls ‐ Divinitus 37 Takapuna Grammar ‐ Leonessa 61 St Cuthbert's College ‐ Black Watch Singers 62 Orewa College ‐ Four Octaves BREAK BREAK BREAK 10.50 WELCOME ( Session 1) 11.00 15 King's College ‐ King's College Chapel Choir 11.00 38 St Peter's College ‐ St Peter's College Senior Choir 11.00 63 Kristin School ‐ Euphony 11.00 1 Dilworth School ‐ Dilworth Foundation Singers 16 Saint Kentigern College ‐ Musettes 39 Diocesan School for Girls ‐ Diocesan Senior Choir 64 Epsom Girls' Grammar ‐ Epsom Singers Whangaparaoa College ‐ 2 Rosehill College ‐ Rosehill Harmony 17 40 Rangitoto College ‐ The Fundamentals 65 Westlake -

NCEA How Your School Rates: Auckland

NCEA How your school rates: Auckland Some schools oer other programmes such as Level 1 Year 11 NA Results not available L1 International Baccalaureate and Cambridge Exams L2 Level 2 Year 12 L3 Level 3 Year 13 point increase or decrease since 2012 UE University Entrance % of students who passed in 2013 % Decile L1 L2 L3 UE Al-Madinah School 2 84.6 -15.4 95.6 -4.4 100 0 93.3 -0.8 Albany Senior High School 10 90.7 5.3 91.7 3.2 91 11 84.1 14.5 Alfriston College 3 75.4 9 70.3 -5.1 66 -0.1 46.9 5.4 Aorere College 2 58.8 0.3 75.3 5.8 68.8 9.8 57.7 13.7 Auckland Girls’ Grammar School 5 80 5.7 81.5 3.9 68.2 -10.6 61.3 -12.4 Auckland Grammar School 10 46.1 37.8 79 2.1 66.4 1.4 54.9 -15.7 Auckland Seventh-Day Adventist High School 2 54.1 -3 45.6 -42.9 73 3.6 57.6 7.6 Avondale College 4 78.8 3.7 87.5 6.7 79.9 8.3 78.9 12.3 Baradene College of the Sacred Heart 9 98.7 5.2 100 0 97.8 4 96.3 4 Birkenhead College 6 80.5 4.4 80.1 -12.8 73.3 0.3 62 -2 Botany Downs Secondary College 10 90.6 -0.4 91.8 -0.1 88.3 8 84.8 6.9 Carmel College 10 97.4 -1.2 99.2 2 97 2.7 93.4 4.7 De La Salle College 1 79.7 9.5 75.1 5.5 59.1 -5.1 54.8 15.6 Dilworth School 4 81.7 -0.3 88.3 4.3 77.9 -7.1 71.1 -7.2 Diocesan School for Girls 10 98.3 0.2 96.6 -2.7 96.4 3.3 96.4 2.5 Edgewater College 4 89.5 8 80.6 -3.7 73.2 10.4 51.7 3.4 Elim Christian College 8 93.3 15.1 88.8 5.8 86.9 -3.2 91.3 5.1 Epsom Girls’ Grammar School 9 92.3 0.7 94.5 2.8 86.7 2.4 89.2 4.9 Glendowie College 9 90 -2.5 91.1 0.8 82.4 -3.8 81.8 1.5 Gleneld College 7 67.2 -9.3 78.6 5.4 72.5 -6.9 63.2 0.5 Green Bay High -

Rainbowyouth Annual Report 2019

RainbowYOUTH Annual Report 2019 Celebrating 30 Years of RainbowYOUTH Who We Are RainbowYOUTH is a charitable organisation that was established in 1989. RainbowYOUTH is here to work with queer, gender diverse and intersex youth as well as their wider communities. Our motto is “know who you are, be who you are”. Tīwhanawhana Trust have gifted us a version of our motto in te reo Māori: “Whāia tō ake ngā kaunui, i te pono, i te mārama”. Simply translated, it means: follow your desires with truth and clarity”. Our Vision All young people thrive in Aotearoa. He waka eke noa (A waka which we are all in together, without exception). Our Mission To create social change in Aotearoa by providing support, information and advocacy for queer, gender diverse and intersex youth, their friends, whānau, and communities. Our Values • Affirming and empowering young people from all walks of life We affirm and empower young people of all abilities, religions, countries, communities and backgrounds. • Young people determining their journey We know that young people are the experts when it comes to what they need and want, and we create the space for them to make that happen. • Proactively and respectfully honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi We recognise the importance of honouring Te Tiriti, and are incorporating this into our kaupapa, our work and organisation. • Strengths-based advocacy We know that our young people are brave, resilient, courageous, generous, and so many other great things. We advocate for and with them by focussing on those strengths. • For youth, by youth Our services, groups, events and organisation are made for youth, and are led by youth. -

Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board Meeting Held on 3/12/2019

Memo 1st October 2019 To: Helen Taimarangai, Senior Grants Advisor From: Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board Subject: Excellence Awards panel decisions 1st October 2019 Purpose 1. To confirm the Excellence Awards Panel decisions made on 1st October 2019. Pursuit of Excellence Panel 2. The panel met today to discuss recent applications received for the Excellence awards. 3. Pursuant to local board resolution, the Excellence panel, OP/2018/144 under delegated authority from the local board, considered the applications and have decided to grant as follows: Applicant Conference/event Amount Amount approved applied for 1 Omar Dada – On Tournament of Minds International $2,000 $2,000 behalf of Papatoetoe Finals – Hobart, Tasmania High Schools – Tournament of Minds International Students. Further considerations 4. As discussed during the panel meeting, grantees are to be encouraged to share an update of their funded activities with the local board. It is the intention of the local board to also share these updates, where possible, with the community as part of their accountability process. Delegation to the panel 5. The panel was delegated decision making to make these grants in August 2018 in the following resolution of the Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board. 2019/2020 Otara-Papatoetoe Local Board Excellence Awards 012 Omar Dada Papatoetoe High School Tournament of Minds International Finals Physical address Papatoetoe, Auckland, NZ Legal status in NZ New Zealand citizenship Age Gender Male Ethnicity African Conflict of interest No Conference/event information Name of Tournament of the Minds – International competition – Hobart Tasmania, Australia conference: Location: Hobart Tasmania, Australia Dates: 24th October 2019 Purpose of Participation at the Tournament of Minds International Finals conference: Contribution to awards objectives Identified objective(s) Celebrate excellence of the local board area How would this build leadership and contribute to identified objective(s) All seven students live in the local area and are proud to. -

Teacher-Led Innovation Fund Round 2: Successful Projects and Schools

Teacher-led Innovation Fund Round 2: Successful Projects and Schools Lead School Name Partner schools involved Supported by Project description Length of Project Hagley Community College Avonside Girls' High School Catholic University of Canterbury The inquiry project is about advancing literacy to improve 2 years Cathedral College outcomes for students entering university. Ao Tawhiti Unlimited Discovery Stanley Bay School Vision Education Evaluation Associates The inquiry project plans to identify teaching practices that promote 2 years self-directed learning across the curriculum. Maketu School Maketu EduCare Core NZ The inquiry project is about exploring mathematics using digital 18 months technology. East Taieri School St Clair School Core NZ The inquiry project focuses on investigating teacher practices that 2 years support student agency, engagement and learning. Manurewa Intermediate Cognition Education The inquiry project is about innovative teacher practice using 2 years materials in mathematics to support learning new concepts. Chanel College St Patrick’s College (Silverstream) MPI The inquiry project is about enhancing students’ outcomes in 2 years St Patrick’s College (Wellington) Futureintech technology in a number of Catholic secondary schools. St Bernard’s College Sacred Heart College (Lower Hutt) Garin College St Catherine’s College (Kilbirnie) Bishop Viard College Pegasus Bay School University of Canterbury The inquiry project plans to develop teacher practice in order to 2 years Core Education increase student agency and whānau engagement in the modern Solo Taxonomy learning environment (MLE). Linc-Ed Building Learning Power E-Time Darfield Primary School Annabel’s Educare (Darfield) University of Canterbury The inquiry project focuses on the transition between ECE and primary 2 years schooling in relation to literacy achievement, particularly for Māori boys and writing. -

Minutes of Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board

Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board OPEN Minutes Minutes of a meeting of the Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board held in the Totara Room, Level 1, Manukau Civic Building, 31-33 Manukau Station Road, Manukau on Tuesday, 17 September 2019 at 5.00pm. PRESENT Chairperson Lotu Fuli Members Apulu Reece Autagavaia Dr Ashraf Choudhary, QSO, JP Mary Gush (from 5.03pm) Dawn Trenberth ABSENT Deputy Chairperson Ross Robertson, QSO, JP Donna Lee ALSO PRESENT Governance Director Phil Wilson to 5.41pm Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board 17 September 2019 1 Welcome The Chair Lotu Fuli led the meeting in prayer. 2 Apologies Resolution number OP/2019/128 MOVED by Chairperson L Fuli, seconded by Member D Trenberth: That the Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board: a) accept the apologies from Deputy Chair Ross Robertson and Member Donna Lee for absence. CARRIED Note: Apologies received from Councillor Filipaina and Councillor Collins for absence. 3 Declaration of Interest There were no declarations of interest. 4 Confirmation of Minutes Resolution number OP/2019/129 MOVED by Chairperson L Fuli, seconded by Member A Choudhary: That the Ōtara-Papatoetoe Local Board: a) confirm the ordinary minutes of its meeting, held on Tuesday, 20 August 2019, as true and correct. CARRIED 5 Leave of Absence There were no leaves of absence. Member M Gush joined the meeting at 5.03 pm. 6 Acknowledgements 6.1 Mr Jagjit Singh Kathuria The Otara-Papatoetoe Local Board wishes to acknowledge and congratulate Mr Jagjit Singh Kathuria, an 81 years old Papatoetoe resident, for his winning two silver medals in 80-84 years old category; one in Triple Jump and one in 3 km Race Walk at the 2019 (31 August-7 September) Oceania Masters Athletics Championships held in Mackay in Queensland, Australia. -

Past Winners

Aerobics 1996 Angela McMillan Rutherford College 1997 Angela McMillan Rutherford College 1998 Danica Aitken Epsom Girls Grammar School 1999 Danica Aitken Epsom Girls Grammar School 2000 Melissa Marcinkowski Westlake Girls High School 2001 Kylie O’Loughlin Epsom Girls Grammar School 2002 Katy McMillan Avondale College 2003 Tony Donaldson Avondale College Katy McMillan Avondale College 2004 Tony Donaldson Avondale College Eleanor Cripps Epsom Girls Grammar School 2005 Michelle Barnett Mt Albert Grammar School 2006 Jennifer Ayers Mt Albert Grammar School 2007 Honor Lock Avondale College Artistic Gymnastics 1993 Rachel Vickery Rangitoto College 1994 Nicholas Hall Wesley College Sarah Thompson Westlake Girls High School 1995 David Phillips Mt Roskill Grammar School Pania Howe Kelston Girls’ High School 1996 Wayne Laker Manurewa High School Laura Robertson Westlake Girls High School 1997 Renate M Nicholson St Cuthbert’s College 1997 Tim De Alwis Rangitoto College Laura Robertson Westlake Girls High School 1998 Tim De Alwis Rangitoto College Laura Robertson Westlake Girls High School 1999 Slarik Shorinor Glenfield College Laura Robertson Westlake Girls High School 2000 Umesh Perinpanayagam Westlake Boys High School Fiona Gunn Baradene College 2001 Daniel Good Saint Kentigern College Alethea Boon Westlake Girls High School 2002 Adrian Coman Massey High School Melynne Rameka Pukekohe High School 2003 Patrick Peng Auckland Grammar School Kate Brocklehurst Baradene College 2004 Kane Rutene Glendowie College Georgia Cervin Westlake Girls High School -

Ministry of Education

SCHEDULE OF DECISION OF MINISTER OF EDUCATION EDUCATION PURPOSE DESIGNATIONS PROPOSED AUCKLAND UNITARY PLAN PAUP Decision Report Reference Common Name Location (Address) Designation Purpose Decision of Minister Annexure 3 - Changes to text - Site Specific Conditions Designation # (s151(2) letter) NORTH & WEST 4500 Albany Junior High School Appleby Road, Albany Highway Educational Purposes - Junior High School (years 7 - 10) ACCEPT Report #2 4501 Albany School 6 Bass Road, Albany Educational Purposes - Primary School (years 0 - 8) ACCEPT Report #2 4502 Albany Senior High School 536 & 546 Albany Highway Educational Purposes - Senior High School (years 11 - 13) ACCEPT Where any construction works for a project involve total or substantial demolition of, or modifications to, a scheduled historic heritage place, any outline lan that is requried shall incorporate: a. An assessment of the effects on the historic heritage values of the scheduled historic heritage place; b. a consideration of alternative methods and/or appropriate mitigation to prevent or avoid damage, loss or destruction of the values of the scheduled historic heritage place; c. an analysis of the extent to which the construction works are required or desirable to enable educational activities to be carriedout; and d. an assessment of the extent to which the construction works are necessary to address safety concerns and/or the extent to which the costs associated with overcoming safety concerns offset the values Report #3 associated with the scheduled historic heritage plac. This condition shall not apply in respect of repair or maintenance of the scheduled historic heritage place. This condition shall not apply where there is a conservation plan or similar plan for the management of the scheduled historic heritage place and the proposed construction works are in accordance with this conservation or similar plan. -

NZ Engineering Science Competition Judges Report 2020

NZ Engineering Science Competition Judges Report 2020 The twelfth annual “NZ Engineering Science Competition” was held from 10am to 6pm on Saturday 1st August 2020. We had 267 teams take part with entries from 81 schools across New Zealand plus our first Cook Island team. The question posed to students this year was: “How many satellites can be launched into orbit before astronomers on Earth can no longer observe the night sky without interruption?” This question is very topical as Elon Musk’s company SpaceX is planning to launch tens of thousands of Starlink satellites in the near future in an effort to offer easy to access satellite internet. Starlink is not the only planned satellite internet constellation planned, with Amazon Kuiper one potential competitor. Given that only a few thousand satellites are currently in orbit around Earth, it looks like the space around Earth is about to get a whole lot busier in the coming years. Proposals for satellite internet constellations, which will be placed in a low Earth orbit, have been met with alarm from the astronomical community. Astronomers are concerned that a sudden increase in satellite traffic in low Earth orbit will seriously impact their ability to observe and study the Universe using ground-based telescopes. It is common to think of technological advancement and scientific research going hand in hand, but this issue challenges us to reconsider the nature of the interaction between modern technology and our pursuit of scientific research. The question this year, which as usual was deliberately open-ended, was mathematically challenging and allowed for many different approaches.