Study List Application of Chavis Park, Raleigh NC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bring Your Family Back to Cary. We're in the Middle of It All!

Bring Your Family Back To Cary. Shaw Uni- versity North Carolina State University North Carolina Museum of Art Umstead State Park North Carolina Museum of History Artspace PNC Arena The Time Warner Cable Music Pavilion The North Carolina Mu- seum of Natural History Marbles Kids Museum J.C. Raulston Arbore- tum Raleigh Little Theatre Fred G. Bond Metro Park Hemlock Bluffs Nature Preserve Wynton’s World Cooking School USA Baseball Na- tional Training Center The North Carolina Symphony Raleigh Durham International Airport Bond Park North Carolina State Fairgrounds James B. Hunt Jr. Horse Complex Pullen Park Red Hat Amphitheatre Norwell Park Lake Crabtree County Park Cary Downtown Theatre Cary Arts Center Page-Walker Arts & History Center Duke University The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill We’re in the middle of it all! Book your 2018 or 2019 family reunion with us at an incredible rate! Receive 10% off your catered lunch or dinner of 50 guests or more. Enjoy a complimen- tary upgrade to one of our Hospitality suites or a Corner suite, depending on availability. *All discounts are pretax and pre-service charge, subject to availability. Offer is subject to change and valid for family reunions in the year 2018 or 2019. Family reunions require a non-refundable deposit at the time of signature which is applied to the master bill. Contract must be signed within three weeks of receipt to take full advantage of offer. Embassy Suites Raleigh-Durham/Research Triangle | 201 Harrison Oaks Blvd, Cary, NC 27153 2018 www.raleighdurham.embassysuites.com | 919.677.1840 . -

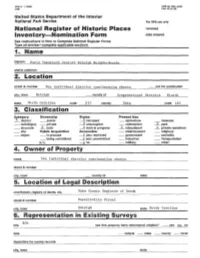

National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form 1

NPS FG--' 10·900 OMS No. 1024-0018 (:>82> EXP·10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS u.e only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory-Nomination Form date entered See Instructions In How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Early -r«entieth Century Raleigh Neighborhoods andlor common 2. Location street & number See individual district continuation sheets _ not for publication city, town Raleigh _ vicinitY of Congressional District Fourth state North Carolina code 037 county Hake code 183 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use ~dlstrlct _public ----.K occupied _ agriculture _museum _ bulldlng(s) _private J unoccupied _ commercial X park _ structure -'L both ----X work In progress l educational l private residence _site Public Acquisition Accessible _ entertainment _ religious _object _In process ----X yes: restricted _ government _ scientific _ being considered --X yes: unrestricted _ Industrial _ transportation N/A -*no _ military __ other: 4. Owner of Property name See individual dis trict continuation sheets street & number city, town _ vicinitY of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Hake County Register of Deeds street & number Fayetteville Street city, town Raleigh state North Carolina 6. Representation in Existing Surveys NIA title has this property been determined eligible? _ yes XX-- no date _ federal __ state _ county _ local depository for survey records city, town state ·- 7. Description Condition Check one Check one ---K excellent -_ deteriorated ~ unaltered ~ original site --X good __ ruins -.L altered __ moved date _____________ --X fair __ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance Description: Between 1906 and 1910 three suburban neighborhoods -- Glenwood, Boylan Heights and Cameron Park -- were platted on the northwest, west and southwest sides of the City of Raleigh (see map). -

Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963

SUTTELL, BRIAN WILLIAM, Ph.D. Campus to Counter: Civil Rights Activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, 1960-1963. (2017) Directed by Dr. Charles C. Bolton. 296 pp. This work investigates civil rights activism in Raleigh and Durham, North Carolina, in the early 1960s, especially among students at Shaw University, Saint Augustine’s College (Saint Augustine’s University today), and North Carolina College at Durham (North Carolina Central University today). Their significance in challenging traditional practices in regard to race relations has been underrepresented in the historiography of the civil rights movement. Students from these three historically black schools played a crucial role in bringing about the end of segregation in public accommodations and the reduction of discriminatory hiring practices. While student activists often proceeded from campus to the lunch counters to participate in sit-in demonstrations, their actions also represented a counter to businesspersons and politicians who sought to preserve a segregationist view of Tar Heel hospitality. The research presented in this dissertation demonstrates the ways in which ideas of academic freedom gave additional ideological force to the civil rights movement and helped garner support from students and faculty from the “Research Triangle” schools comprised of North Carolina State College (North Carolina State University today), Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Many students from both the “Protest Triangle” (my term for the activists at the three historically black schools) and “Research Triangle” schools viewed efforts by local and state politicians to thwart student participation in sit-ins and other forms of protest as a restriction of their academic freedom. -

Chavis Park Carousel Landmark Designation Report Prepared for the Raleigh Historic Districts Commission

Chavis Park Carousel Landmark Designation Report Prepared for the Raleigh Historic Districts Commission Originally Prepared January 2001 By M. Ruth Little Longleaf Historic Resources Revised February 2008 By April Montgomery Circa, Inc. 1 of 18 Physical Description The Chavis Park Carousel stands in the center of Chavis Park on Chavis Way. It is sheltered within a frame pavilion on the south side of Park Road, an internal street within the park. The twenty‐three acre park is located in southeast Raleigh between East Lenoir Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. The carousel was installed in the park on July 2, 1937. Experts estimate the date of manufacture of the carousel to be between 1916 and 1923, because it closely resembles a documented 1916 Herschell Carousel1. Carousel: The carousel, known as a ʺNo. 2, Special Three Abreast, Allan Herschell Carousel, was purchased from the Allan Herschell Company of North Tonawanda, New York, for $4,000 in 1937. The carousel had been designed and used for traveling shows originally, and was refurbished prior to its sale to the City of Raleigh. The Herschell Company catalogue describes this model as a forty‐foot carousel containing: thirty‐six hand‐carved horses (outer row studded with jewels) and two beautifully carved double‐seat Chariots. Passenger capacity 48 persons. All horses are jumpers. Horse Hanger pipe and platform hanger pipe is encased in polished Brass. The Cornice, Shields and panel Picture Center are highly decorated works of art and are wired for 196 lights. Oil paintings and hand carvings combine with bright colors to produce a beautiful and practical machine. -

Raleigh Register Summer 2020

Vol 24 summer 2020 Raleigh Register Official Newsletter of the Historic Resources and Museum Program The grounds at Mordecai Historic Park 418418 N N. Person Person Street, Street Raleigh,Raleigh, NC, NC 27601 27601 919.996.4772919.857.4364 www.raleighnc.gov/museums www.raleighnc.gov/museums 2 Administrator’s Letter Chair’s Letter Hello! We hope you enjoy reading this As access to many City issue of the Raleigh Register and enjoy of Raleigh sites may be limited, learning about fun facts and hidden now is a perfect time to catch up on histories at the different sites managed some of the stories behind these by the Historic Resources and Museum places. One of my favorite sites at this Program. A zoo at Pullen Park? A hair salon at Pope House time of year is the grounds of the Mordecai House. Museum? An orphanage at Borden Building? How about a school at Moore Square? Over the years, uses at each site In Gleanings from Long Ago, Ellen Mordecai shared changed over time. Families even altered our venerable her memories of growing up at Mordecai Plantation in buildings such as the Mordecai House or the Tucker House the 19th century and how she and her family shaped, to reflect contemporary tastes and/or needs. Throughout the and were shaped by, the surrounding landscape. In course of each sites’ history, at each site the one constant her description of the grounds, Ellen recalled the remained: change. During these uncertain times, we can all graceful walnut trees that dotted the landscape and find solace in this simple truth. -

Raleigh Parks, Recreation and Cultural Resources Internship Manual

Raleigh Parks, Recreation and Cultural Resources Internship Manual Raleigh Parks, Recreation and Cultural Resources Department 222 West Hargett Street, Suite 608 Raleigh, NC 27602 919-996-6640 Parks.raleighnc.gov For Additional Information About Internships: Email [email protected] Internship Manual Contents • Note from the Director • Welcome to Raleigh • City of Raleigh Overview • Mission Statement • History of Department • Department Overview • Intern Qualifications • Intern Guidelines • Internship Goals • Internship Responsibilities • Policy & Procedures • FAQ’s A Note from the Director of Raleigh Parks, Recreation and Cultural Resources Dear Students, Educators, and Fellow Professionals: The Raleigh Parks, Recreation and Cultural Resources Department is pleased to present our Internship Manual for your review and consideration. Within this Manual, you will find information on all of the opportunities our internship program offers. All undergraduate students are encouraged to apply as we offer a variety of internships that encompass an array of educational disciplines and backgrounds. Students who choose to intern with us will experience on-site training from a nationally recognized parks and recreation department, professional supervision and feedback from experienced and qualified supervisory staff, and an opportunity to gain exposure from a very diverse collaborative system. We look at this as an opportunity for you and our district to grow in the search for excellence. We look forward to working with you and having you assist us in our efforts to improve the quality of life for our citizens and visitors. Sincerely, Diane Sauer Welcome to Raleigh, the Capital City of NC and the Seat of State Government. It is also the home of Pullen Park, the Carolina Hurricanes and numerous colleges and universities. -

Technician \ North Carolina State University's

Technician \ North Carolina State University’s Student Newspaper Since 1920 Phone 737-2411,-2412 Wednesday, June 16, 1m Raleigh. North Cardina Volume LXIII Number 90 Staff photo by Sam Adams- Summer, 1982 / Technician'2 Th rough the years of enlight enment by Fred W. Brown 'freedom’ yet. freshman. next two years of college easy trap to fall could turn into nothing but Features Don't tell me you’re not But it's an looking forward to getting into. By your junior year, you wasted time, effort, and Booze! Rock 'n roll! Drugs! away from Mama's apron str- probably will have decided money. Sex! -If you're a normal, ings. what you want to do with healthy, red-blooded That is why I chose 'booze' your life. If you haven’t, it You’ve probably figured American college freshman, to characterize your might be a good idea to take out by now how sex and the you are already well ac- freshman year. a break from school for senior year go together. quainted with each of these One day of freedom can be awhile. The key to your That’s right. The last year is terms. If you are, you have twice as intoxicating as a junior year is knowing what the edge on those who aren’t. whole case of beer. And if you want to do when you However, for those of you that's how one day feels, im- graduate and using your who have led sheltered lives, agine howl giddy you’ll be junior year to help you or for the rest of you who when you realize you’re on prepare for that. -

Historic Properties Commission 1961 ‐ 1972 Activities and Accomplishments

HISTORIC PROPERTIES COMMISSION 1961 ‐ 1972 ACTIVITIES AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS 1961 – 1967 ▫ Improved City Cemetery and repaired Jacob Johnson monument ▫ Established Capital City Trail in collaboration with Woman’s Club ▫ Published brochures ▫ Laid foundation for interest and education regarding early post office building, Richard B. Haywood House, Mordecai House ▫ Marked historic sites, including Henry Clay Oak and sites in Governorʹs Mansion area June 1967 ▫ Instrumental in passing local legislation granting City of Raleigh’s historic sites commission additional powers ▫ City acquired Mordecai House ▫ Mordecai property turned over to commission to develop and supervise as historic park (first example in state) December 1967 ▫ Partnered with Junior League of Raleigh to publish the book North Carolinaʹs Capital, Raleigh June 1968 ▫ Moved 1842 Anson County kitchen to Mordecai Square, placing it on approximate site of former Mordecai House kitchen August 1968 ▫ City Council approved Mordecai development concept November 1968 ▫ City purchased White‐Holman House property; commission requested to work on solution for preserving house itself; section of property utilized as connector street March 1969 ▫ Supervised excavation of Joel Lane gravesite April 1969 ▫ Collaborated with City to request funds for HUD grant to develop Mordecai Square June 1969 ▫ Lease signed for White‐Holman House September 1969 ▫ Blount Street preservation in full swing May 1970 ▫ Received $29,750 HUD grant for Mordecai development June 1970 ▫ Two ʺPACEʺ students inventoried -

City of Raleigh Neighborland Perry Street Studio LLC Dorothea Dix Park Master Plan Community Outreach & Engagement Executive Summary

Public Engagement Source: City of Raleigh Neighborland Perry Street Studio LLC Dorothea Dix Park Master Plan Community Outreach & Engagement Executive Summary The City of Raleigh, with the support of the Dorothea Dix Park Conservancy, is leading a generational effort to develop Dorothea Dix Park. This success of this effort lies in the ability to create a deep and meaningful connection between the community and the park. In terms of scale and scope, the outreach associated with the Master Plan is unprecedented in city projects. This strategy presents a thoughtful, coordinated and ambitious approach to meaningful outreach and engagement. Parks are one of the most democratic spaces in a community. The City of Raleigh has made it a priority to create a diverse and equitable master planning process for Dix Park that serves all of Raleigh’s residents and beyond. The Outreach and Engagement Strategy is couched in an equity framework that details the objectives, implementation, and evaluation of an inclusive and accessible planning process. This strategy takes a multi-faceted and flexible approach to outreach and engagement. From traditional community meetings to experience-based events, programs and online participation, this strategy provides multiple channels to reach a broad and diverse audience. The goal is to provide a variety of opportunities for individuals to explore and shape the future of Dorothea Dix Park. Finally, this strategy was built around the schedule set forth by the Master Plan consultant, Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates (MVVA). Engagement opportunities were be designed to facilitate dialogue between the community and MVVA. The process was iterative with engagement continually informing the evolution of the Dorothea Dix Park Master Plan. -

City Manager's Weekly Report

Issue 2020-37 October 2, 2020 IN THIS ISSUE WakeHelps Utility Customer Assistance Plan Update Park Rentals and Gathering Limits – Phase 3 Restrictions to Protect Lives During the COVID 19 Pandemic Capital Boulevard North Corridor Study - Bikes and Businesses Virtual Engagement Nights of Lights at Dix Park Downtown Pop Up Dog Park Council Follow Up Lane-Idlewild Assemblage Developer Recommendations Dix Park Leadership Committee Meeting: Lake Wheeler Road (Mayor Baldwin) Moseley Lane – Background and Provision of Municipal Services (Council Member Cox) Transportation Bond Projects – Schedules Update (Council Member Cox) GoRaleigh Access Eligibility – Martha Brock – Public Comment (Mayor Pro Tem Branch, Mayor Baldwin) Sidewalk Project Updates (Council Member Buffkin) INFORMATION: Regular Council Meeting Tuesday, October 6 - Afternoon and Evening Sessions Reminder that Council will meet next Tuesday in regularly scheduled sessions at 1:00 P.M. and 7:00 P.M. The agenda for the meeting was published on Thursday: https://go.boarddocs.com/nc/raleigh/Board.nsf Please note there will be a Closed Session immediately following the afternoon session of the Council meeting. Reminder: If there is an item you would like to have pulled from the consent agenda for discussion, please send an e-mail [email protected] by 11 A.M. on the day of the meeting. Weekly Report Page 1 of 24 October 2, 2020 Issue 2020-37 October 2, 2020 WakeHelps Utility Customer Assistance Plan Update Staff Resource: Aaron Brower, Raleigh Water, 996-3469, [email protected] Council may recall that Wake County allocated $5,000,000 of federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act funding to be used towards utility bill assistance. -

About Raleigh, North Carolina the City Began to Take Off When the Research Triangle Raleigh History Park Opened in 1959

Photo Courtesy of visitRaleigh.com About Raleigh, North Carolina the city began to take off when the Research Triangle Raleigh History Park opened in 1959. For 60 years, the Research Triangle In the same year that Kentucky officially became a Park has supported collaboration and advancement state, Raleigh was founded in 1792 as North Carolina’s among universities, companies, and citizens of North capital city. It was named for Sir Walter Raleigh, who at- Carolina. tempted to establish the first English colony on the shores of the new world in the 1580’s. It is the only state capital to have been planned and established by a state Raleigh Today as the seat of state government. In March 1792, com- Today, Raleigh is the largest city in a combined sta- missioners selected a tract of land owned by Joel Lane tistical area known as Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill (the for the new capital at a cost of $2,756. Sen. William Research Triangle Region). It is consistently among the Christmas, a surveyor, was hired to lay out the new city. most educated cities in the nation, boasting 12 colleges In November 1792, the North Carolina General Assem- and universities, including three tier-one research uni- bly chose the name "Raleigh" for its capital city. The city's versities that are catalyzing global innovation. In Wake founding fathers called Raleigh the "City of Oaks" and County, the percentage of the population with a bache- dedicated themselves to maintaining the area's wooded lor’s degree or higher is nearly double the state and na- tracts and grassy parks. -

U Technician North Carolina State University's Student Newspaper

u Technician North Carolina State University's Student Newspaper Since 1920 Volume LVlI, Number 27 Monday, November 1, 1976 ' WKNC to air election results byGregRogers University in Boone. reporter from the student newspaper at cent for national races and 60 per cent for News Editor ' SAM TAYLOR, assistant news director UNC-G hasagreedtocoverelection results state-wide races. Races of primary at WKNC. told the Technician Sunday from the Jimmy Carter headquarters in importance to the network would be the WKNC-FM. along with four other approximately six reporters will be sent to Atlanta. Ga. presidential. guberantorial. lieutenant student-operated radio stations. will pro- the Democratic headquarters at the Hilton Several political scientists from UNC-G gubernatorial. labor commissioner. super- vide coverage of national. state-wide and Inn. two to three reporters to Republican have offered their assistancw in interpret- intendent, of public instruction. state local elections Tuesday night. gubernatorial candidate David Flaherty's ing the election results. and Taylor said auditor' and state treasurer. Approximately 30 students from parti—. headquarters at the Sheraton Inn at “hopefully this will help us to make some “We'redefintely going to concentrate on cipatingradio stations. which have banded Crabtree Valley. and six reporters to the predictions ourselves." getting results which have importance to together to form the North Carolina remaining Republican candidates' head- OFTHE so students participating in the North Carolina as a whole." Taylor said. University Radio Network (URNET). will quarters at the Royal Villa. election night coverage. Taylor said 15 HE ALSO SAID between election provide election coverage beginning at He said the remaining staff members would be involved from WKNC.