Methods of Making Use of Tax Havens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Government of the Hungarian People's Republic

CONVENTION BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HUNGARIAN PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC AND THE GOVERNMENT OF THE ITALIAN REPUBLIC FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME AND CAPITAL AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION.1 The Government of the Hungarian People's Republic and the Government of the Italian Republic, desiring to promote and facilitate the economic relations between the two countries, have agreed to conclude a Convention for the avoidance of double taxation with respect to taxes on income and capital and the prevention of fiscal evasion of which the provisions are the following: Article 1 - Personal scope This Convention shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States. Article 2 - Taxes covered 1. This Convention shall apply to taxes on income and on capital imposed on behalf of each Contracting State or its political or administrative subdivisions or local authorities, irrespective of the manner in which they are levied. 2. There shall be regarded as taxes on income and on capital taxes imposed on total income, on total capital, or on elements of income or of capital, including taxes on gains from the alienation of movable or immovable property, taxes on the total amounts of wages or salaries paid by enterprises, as well as taxes on capital appreciation. 3. The existing taxes to which this Convention shall apply are the following: (a) in the case of the Italian Republic: (1) the individual income tax (imposta sul reddito delle persone fisiche); (2) the tax on the income of legal entities (imposta sul reddito delle persone giuridiche); and (3) the local income tax (imposta locale sui redditi), even if withheld at the source (hereinafter referred to as "Italian tax"); (b) in the case of the Hungarian People's Republic: (1) the income taxes (j”vedelemad¢k); (2) the profit taxes (nyeres‚gad¢k); (3) the enterprises' special tax (v llalati kl”nad¢); (4) the tax on buildings (h zad¢); 1 Date of Conclusion: 16 May 1977. -

Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)

Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) BEPS Action 7 Additional Guidance on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments 4 October 2017 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AFME and UK Finance .................................................................................................................. 5 Andrew Cousins & Richard Newby ............................................................................................... 8 Andrew Hickman ............................................................................................................................ 13 ANIE (Federazione Nazionale Imprese Elettrotecniche ed Elettroniche) ....................................... 19 Association of British Insurers ....................................................................................................... 22 BDI ...... .......................................................................................................................................... 24 BDO...... .......................................................................................................................................... 26 BEPS Monitoring Group ................................................................................................................ 29 BIAC ... .......................................................................................................................................... 47 BusinessEurope ............................................................................................................................. -

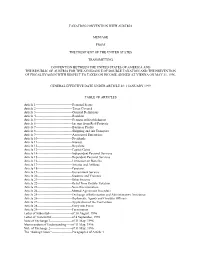

Taxation Convention with Austria Message from The

TAXATION CONVENTION WITH AUSTRIA MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING CONVENTION BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF AUSTRIA FOR THE AVOIDANCE OF DOUBLE TAXATION AND THE PREVENTION OF FISCAL EVASION WITH RESPECT TO TAXES ON INCOME, SIGNED AT VIENNA ON MAY 31, 1996. GENERAL EFFECTIVE DATE UNDER ARTICLE 28: 1 JANUARY 1999 TABLE OF ARTICLES Article 1----------------------------------Personal Scope Article 2----------------------------------Taxes Covered Article 3----------------------------------General Definitions Article 4----------------------------------Resident Article 5----------------------------------Permanent Establishment Article 6----------------------------------Income from Real Property Article 7----------------------------------Business Profits Article 8----------------------------------Shipping and Air Transport Article 9----------------------------------Associated Enterprises Article 10--------------------------------Dividends Article 11--------------------------------Interest Article 12--------------------------------Royalties Article 13--------------------------------Capital Gains Article 14--------------------------------Independent Personal Services Article 15--------------------------------Dependent Personal Services Article 16--------------------------------Limitation on Benefits Article 17--------------------------------Artistes and Athletes Article 18--------------------------------Pensions Article 19--------------------------------Government Service Article 20--------------------------------Students -

Explanation of Proposed Income Tax Treaty Between the United States and Hungary

EXPLANATION OF PROPOSED INCOME TAX TREATY BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND HUNGARY Scheduled for a Hearing Before the COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE On June 7, 2011 ____________ Prepared by the Staff of the JOINT COMMITTEE ON TAXATION May 20, 2011 JCX-32-11 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 I. SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 2 II. OVERVIEW OF U.S. TAXATION OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND INVESTMENT AND U.S. TAX TREATIES ....................................................................... 4 A. U.S. Tax Rules ................................................................................................................. 4 B. U.S. Tax Treaties .............................................................................................................. 6 III. OVERVIEW OF TAXATION IN HUNGARY .................................................................... 8 A. National Income Taxes ..................................................................................................... 8 B. International Aspects ...................................................................................................... 11 C. Other Taxes .................................................................................................................... 13 IV. THE UNITED STATES AND HUNGARY: CROSS-BORDER INVESTMENT AND -

Handbuch Investment in Germany

Investment in Germany A practical Investor Guide to the Tax and Regulatory Landscape in Germany 2016 International Business Preface © 2016 KPMG AG Wirtschaftsprüfungsgesellschaft, a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. Investment in Germany 3 Germany is one of the most attractive places for foreign direct investment. The reasons are abundant: A large market in the middle of Europe, well-connected to its neighbors and markets around the world, top-notch research institutions, a high level of industrial production, world leading manufacturing companies, full employment, economic and political stability. However, doing business in Germany is no simple task. The World Bank’s “ease of doing business” ranking puts Germany in 15th place overall, but as low as 107th place when it comes to starting a business and 72nd place in terms of paying taxes. Marko Gründig The confusing mixture of competences of regional, federal, and Managing Partner European authorities adds to the German gift for bureaucracy. Tax KPMG, Germany Numerous legislative changes have taken effect since we last issued this guide in 2011. Particularly noteworthy are the Act on the Modification and Simplification of Business Taxation and of the Tax Law on Travel Expenses (Gesetz zur Änderung und Ver einfachung der Unternehmensbesteuerung und des steuerlichen Reisekostenrechts), the 2015 Tax Amendment Act (Steueränderungsgesetz 2015), and the Accounting Directive Implementation Act (Bilanzrichtlinie-Umsetzungsgesetz). The remake of Investment in Germany provides you with the most up-to-date guide on the German business and legal envi- ronment.* You will be equipped with a comprehensive overview of issues concerning your investment decision and business Andreas Glunz activities including economic facts, legal forms, subsidies, tariffs, Managing Partner accounting principles, and taxation. -

94 Commentary on Article 5 Concerning the Definition

COMMENTARY ON ARTICLE 5 CONCERNING THE DEFINITION OF PERMANENT ESTABLISHMENT 1. The main use of the concept of a permanent establishment is to determine the right of a Contracting State to tax the profits of an enterprise of the other Contracting State. Under Article 7 a Contracting State cannot tax the profits of an enterprise of the other Contracting State unless it carries on its business through a permanent establishment situated therein. 1.1 Before 2000, income from professional services and other activities of an independent character was dealt under a separate Article, i.e. Article 14. The provisions of that Article were similar to those applicable to business profits but it used the concept of fixed base rather than that of permanent establishment since it had originally been thought that the latter concept should be reserved to commercial and industrial activities. The elimination of Article 14 in 2000 reflected the fact that there were no intended differences between the concepts of permanent establishment, as used in Article 7, and fixed base, as used in Article 14, or between how profits were computed and tax was calculated according to which of Article 7 or 14 applied. The elimination of Article 14 therefore meant that the definition of permanent establishment became applicable to what previously constituted a fixed base. Paragraph 1 2. Paragraph 1 gives a general definition of the term “permanent establishment” which brings out its essential characteristics of a permanent establishment in the sense of the Convention, i.e. a distinct “situs”, a “fixed place of business”. The paragraph defines the term “permanent establishment” as a fixed place of business, through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partly carried on. -

Adopting the New International Tax Rules and Standards How Developing Countries in Asia and the Pacifi C Stand to Benefi T—If They Engage!

The Governance Brief ɆŹƀɆƷɆŹŷŸž Adopting the New International Tax Rules and Standards How Developing Countries in Asia and the Pacifi c Stand to Benefi t—If They Engage! By Richard Highfi eld1 Introduction This brief presents a major challenge for all developing countries, particularly their Mobilizing the domestic resources of developing respective ministries of fi nance and national tax countries and making better use of international administrations that together play a critical role assistance has been the subject of considerable in setting revenue mobilization objectives, and discussion over the past 2 years, and is a key determining strategies and approaches for their direction and commitment refl ected in the Addis realization. Tax Initiative Declaration of 2015,2 and the UN’s In a session at the International Monetary Sustainable Development Goal 17 (Target 1): Fund (IMF)-World Bank Spring Meetings held in April 2016 titled “Collect More and Spend Better,” “Strengthen domestic resource mobilization, it was observed that billions of dollars of potential including through international support to tax revenue remain uncollected each year in many developing countries, to improve domestic developing countries, either due to poor tax system For inquires, comments, 3 capacity for tax and other revenue collection.” design or weaknesses in tax administration. A fair and suggestions, please contact the editor of the Governance Brief, Claudia Buentjen at +632 683 1852 or [email protected], 1 Richard Highfi eld works as consultant with ADB on tax administration and is also an Adjunct Professor with the University SDCC Thematic of New South Wales’ School of Business in Australia. -

OECD Multilateral Instrument Status Tracker

OECD Multilateral Instrument status tracker Current as of 1 June 2019 Introduction 1 Status of the MLI as at 1 June 2019 2 World heat map 2 Europe 3 Asia-Pacific and the Middle East 4 Americas 5 Africa 6 Matrices of CTAs 7 Appendices 15 Contacts 18 OECD Multilateral Instrument status tracker | Introduction Introduction Scope This document is a status tracker for the implementation • OECD BEPS Project – The BEPS project supported by of the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax the G20 now includes over 100 countries. Countries Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and are able to take part in the ongoing work if they Profit Shifting generally referred to as the Multilateral commit to implementation of the agreed minimum Instrument or MLI. This MLI status tracker is intended to standards. consolidate general information on the application of the • OECD Model Tax Convention – The OECD Model treaty. The tracker has been reviewed and updated as of Tax Convention on Income and on Capital is the model 1 June 2019. traditionally used by developed economies when negotiating double tax conventions. As at 1 June 2019, 88 jurisdictions have signed the MLI, and 26 of those jurisdictions have also deposited their • Tax treaty – A tax convention between two instruments of ratification with the OECD. jurisdictions for the avoidance of double taxation with respect to taxes on income and on capital. Please note the following definitions used in the document: The MLI status tracker is intended to be a quick reference guide, and is not an exhaustive overview of all information relating to the MLI. -

Business Location Austria: Tax Aspects

Business Location Austria: Tax Aspects Overview of different forms of taxation In many areas, Austrian tax regulations are tied to the legal form of the taxable entity. The operating income of corporations (page 2) such as the GmbH (limited liability company) and the Aktiengesellschaft (joint stock company) are subject to corporate income taxes, whereas in the case of natural persons (page 16), the Austrian Income Tax Act distinguishes between earnings from business operations and other forms of income, in which case income is determined independently of each other. The total income is then subject to the income tax. Within the context of setting up a company, the question often arises as to precisely when business people are required to register with tax authorities and the scope of activity which will subsequently entail a tax obligation. The chapter “Branch Offices - Permanent Establishments” (page 13) deals with this aspect and related issues of deferred taxes. In addition to personal taxes, so-called “non-personal” exist which depend on the respective circumstances. These include the value added tax, real estate transfer tax, stamp duties and fees for legal transactions. The chapter on corporations provides more details about non- personal taxes. However, for the most part they are independent of the particular legal structure, and thus can also apply to natural persons and production sites. Many fields of activity are supported via tax benefits, namely tax allowances or tax credits. In particular, this includes the 14 percent research tax credit in the field of R&D, which can be claimed for in-house research and contract research. -

Rich Source Countries

CCSI Briefing Note Luis M. Almeida and Perrine Toledano1,2 March 2018 UnderstandingCCSI Briefing Note how the various definitionsLuis of Permanent Almeida and Perrine Establishment Toledano1,2 March 2018 can limit the taxation ability of resource- rich source countries Key CCSI Points Briefing Note Luis Almeida and Perrine Toledano1,2 March 2018 Double Taxation Agreements (DTAs) are bilateral tax treaties that are designed to reduce the negative impact of double taxation through the Understanding 1 allocation of taxing rights to how the State the of residence various (i.e. where thedefinitions company has its base) of and Permanent to the State of source (i.e.Establishment where the taxable operations takes place); canCCSI limit Briefing the Note taxation ability of resource- richLuis so Almeidaurce countries and Perrine Toledano1,2 The allocation of the rights to tax business profits of non-resident entities’ operations depends on whether these operations can constitute a Key1 Points March 2018 2 “Permanent Establishment” (PE) according to the definition included in each DTA. If non-resident entities fulfill the criteria established in this PE definition, taxation is due at the source State. On the contrary, if non-resident entities fall outside of the scope of this definition, the residence State obtains these rights. DTAs can therefore result in source States losing significant tax revenue from operations of non-residents (unless such Ke2 Luis Almeida and Perrine Toledano1,2 UnderstandingCCSIoperations Briefing are conducted Note under -

Permanent Establishment in the Digital Age: Improving and Stimulating Debate Through an Access to Markets Proxy Approach Benjamin Hoffart

Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property Volume 6 Article 6 Issue 1 Fall Fall 2007 Permanent Establishment in the Digital Age: Improving and Stimulating Debate Through an Access to Markets Proxy Approach Benjamin Hoffart Recommended Citation Benjamin Hoffart, Permanent Establishment in the Digital Age: Improving and Stimulating Debate Through an Access to Markets Proxy Approach, 6 Nw. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. 106 (2007). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njtip/vol6/iss1/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. NORTHWESTERN JOURNAL OF TECHNOLOGY AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY Permanent Establishment in the Digital Age: Improving and Stimulating Debate Through an Access to Markets Proxy Approach Benjamin Hoffart Fall 2007 VOL. 6, NO. 1 © 2007 by Northwestern University School of Law Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property Copyright 2007 by Northwestern University School of Law Volume 6, Number 1 (Fall 2007) Northwestern Journal of Technology and Intellectual Property Permanent Establishment in the Digital Age: Improving and Stimulating Debate Through an Access to Markets Proxy Approach By Benjamin Hoffart* ¶1 The contemporary international tax system developed to allocate taxing jurisdiction over buyers and sellers of tangible, physical goods. Accordingly, the current system is based on the actual geographic location of these buyers and sellers. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the preeminent international tax policymaker,1 has incorporated and consistently reaffirmed these physical presence principles in its Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital (“OECD Convention”), the predominant world-wide model for bi- and multi-lateral tax treaties. -

Fiscal Committee National Reports January 2014

CFE Fiscal Committee National Reports January 2014 130 th Meeting Table of Contents Belgium (BE) ........................................................................................................... 3 Czech Republic (CZ)................................................................................................. 5 France (FR) .............................................................................................................. 7 Ireland (IRE) .......................................................................................................... 10 Italy (IT)................................................................................................................. 12 Malta (MT) ............................................................................................................ 15 Romania (RO) ....................................................................................................... 19 Slovak Republic (SK) ............................................................................................. 22 Spain (ES) .............................................................................................................. 25 Switzerland (CH) ................................................................................................... 30 The Netherlands (NL) ............................................................................................ 32 Ukraine (UA) ......................................................................................................... 34 United Kingdom