Turin Shroud, Issue #76, December 2012 (

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shroud News Issue #54 August 1989

ISSUE No 54 A NEWSLETTER ABOUT THE HOLY SHROUD OF TURIN August 1989 edited by REX MORGAN Author of PERPETUAL MIRACLE and SHROUD GUIDE CRUSADER PERIOD PAINTING OF CHRIST IN THE CHURCH OF THE NATIVITY, BETHLEHEM. ANOTHER COPY FROM THE SHROUD? Pic: Sr Damian of the Cross (Dr Eugenia Nitowski) 2 SHROUD NEWS No 54 (August 1989) EDITORIAL The last issue of Shroud News was well received in the many countries it now reaches. In the past few years the number of regular newsletters and magazines on the subject of the Shroud has increased as more and more people in different parts of the world come to grips with the inescapable fact that Sindonology - the study of the Turin Shroud - is more than a passing fad or an interest for a few scientific specialists or religious fanatics. Indeed most people in most places now know something about the Shroud as a result of its rather sensationalised recent history since 1978 and particularly since the far from satisfactory carbon-dating tests which took place last year. Thus study groups are still springing up and some of them produce regular communications. Amongst those received at the Shroud News office are the new Belgian Soudarion which is a large format, well printed magazine in Flemish. Another new American news-sheet is Friends of the Shroud Newsletter, a quarterly mimeographed series of notes and offprints of press items. Amongst the more prestigious and authoritative journals, Shroud Spectrum International No. 30, March 1989, contains two important papers: one on medical aspects of the arm-position by Dr Gilbert Lavoie and yet another intriguing historical debate by the indefatigable Dorothy Crispino who has also presented on the front cover a rare and beautiful miniature painting of Geoffroy I de Charny. -

'Blood' Images

The Shroud of Turin’s ‘Blood’ Images: Blood, or Paint? A History of Science Inquiry Author: David Ford <[email protected]>, a graduate of the University of Maryland Baltimore County that majored in history and philosophy. Date: 10 December 2000 Keywords: Shroud of Turin, ‘blood’ images, McCrone, iron oxide and vermilion paint, Heller & Adler, blood tests “It is the essence of scientific investigation to seek to much ‘blood’ and a clear fluid as if from a lance conform thought to the nature of its object, as wound, and seemingly unbroken legs.10 Because of encountered in its interaction with us.” this close similarity, the image is universally believed -- John Polkinghorne1 to depict Jesus,11 yet much controversy remains about whether the Shroud is Jesus’ actual burial shroud or Introduction merely a forgery. A ‘strong-authenticity’ view holds that the body image was produced by supernatural According to the New Testament’s book of means involving Jesus’ body, while a ‘weak- John, Roman soldie rs “flogged” Jesus of Nazareth, authenticity’ view holds that the body image was “twisted together a crown of thorns and put it on his produced by Jesus’ body via unusual natural head,” “struck him in the face,” and, along with two processes. In both the strong- and weak- authenticity others, “crucified him.”2 Because the next day was views, the ‘blood’ images arose via contact of the unsuitable for the display of crucified individuals, a cloth with a bloody Jesus. request that those crucified have their “legs broken” and their “bodies taken down” was made and A point of argument against the Shroud of granted.3 (With their legs broken, victims of Turin being Jesus’ actual burial cloth is that it can be crucifixion could no longer push up their bodies to traced with certainty only from about AD 1355. -

A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses

TThhee SShhrroouudd ooff TTuurriinn A Critical Summary of Observations, Data and Hypotheses If the truth were a mere mathematical formula, in some sense it would impose itself by its own power. But if Truth is Love, it calls for faith, for the ‘yes’ of our hearts. Pope Benedict XVI Version 4.0 Copyright 2017, Turin Shroud Center of Colorado Preface The purpose of the Critical Summary is to provide a synthesis of the Turin Shroud Center of Colorado (TSC) thinking about the Shroud of Turin and to make that synthesis available to the serious inquirer. Our evaluation of scientific, medical forensic and historical hypotheses presented here is based on TSC’s tens of thousands of hours of internal research, the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) data, and other published research. The Critical Summary synthesis is not itself intended to present new research findings. With the exception of our comments all information presented has been published elsewhere, and we have endeavored to provide references for all included data. We wish to gratefully acknowledge the contributions of several persons and organizations. First, we would like to acknowledge Dan Spicer, PhD in Physics, and Dave Fornof for their contributions in the construction of Version 1.0 of the Critical Summary. We are grateful to Mary Ann Siefker and Mary Snapp for proofreading efforts. The efforts of Shroud historian Jack Markwardt in reviewing and providing valuable comments for the Version 4.0 History Section are deeply appreciated. We also are very grateful to Barrie Schwortz (Shroud.com) and the STERA organization for their permission to include photographs from their database of STURP photographs. -

The Shroud and the "Historical Jesus"

The Shroud and the “Historical Jesus” Challenging the Disciplinary Divide By Simon J. Joseph, Ph.D. © 2012 The Shroud of Turin is virtually ignored in historical Jesus research. Why? In this paper, I will seek to provide an explanation for this curious lack of interest and examine ways in which historical Jesus research and Sindonology might complement each other. Since the 1988 radiocarbon dating test, there has been a general assumption, particularly within the scientific community, that the Shroud is of medieval origin.1 The 1988 test results have largely been regarded as “decisive proof that the Turin Shroud is a forgery.”2 Recent studies, however, indicate that those results are in need of reevaluation.3 This paper will identify a number of distinctive features of the Shroud that have yet to be explained and will correlate these features with historical Jesus research. So why is the Shroud virtually ignored by historical Jesus scholars? The most obvious explanation for this apparent professional negligence is that most biblical scholars have concluded, no doubt as a result of the 1988 radiocarbon dating test, that the Shroud is a medieval forgery. John Dominic Crossan, for example—one of the world’s leading authorities on the historical Jesus—regards the Shroud as a “medieval relic-forgery” and wonders not whether it may be real or not, but “whether it was done from a crucified dead body or from a crucified living body. That is the rather horrible question once you accept it as a forgery.”4 Crossan also proposes that Jesus’ crucified body was not buried, but thrown in a common grave and eaten by dogs.5 The problem with this explanation, however, is that New Testament scholars were ignoring the Shroud long before the 1988 radiocarbon dating test. -

The Shroud of Turin: a Historiographical Approach

THE SHROUD OF TURIN: A HISTORIOGRAPHICAL APPROACH Tristan CASABIANCA Tristancasabianca[at]yahoo.fr This article has been published in final form at The Heythrop Journal, 54, 3, 2013, pp. 414- 23. The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/heyj.12014/abstract ABSTRACT Criteria of historical assessment are applied to the Turin Shroud to determine which hypothesis relating to the image formation process is the most likely. To implement this, a ‘Minimal Facts’ approach is followed that takes into account only physicochemical and historical data receiving the widest consensus among contemporary scientists. The result indicates that the probability of the Shroud of Turin being the real shroud of Jesus of Nazareth is very high; historians and natural theologians should therefore pay it increased attention. I. THE TURIN SHROUD AND A ‘MINIMAL FACTS’ APPROACH The Turin Shroud (TS) is an ancient linen cloth (approximately 4.4 m long and 1.1. m wide) on which is the image of a scourged and crucified man, kept in the cathedral of Turin, Italy; it is one of the most studied and controversial objects ever examined by science. Scientific studies, however, do not always take a sound methodological approach. In 2010 New Testament scholar Michael Licona published a book: The Resurrection of Jesus: A New Historiographical Approach.1 Here he seeks to determine which hypothesis among all those put forward by scholars to explain the resurrection narratives is the most likely. The fundamental point of Licona’s line of reasoning is a determination to assess the hypotheses pertaining to Jesus’ resurrection relying exclusively on a bedrock of facts – that is to say, only on data that are nowadays unanimously or almost unanimously accepted by scholars. -

The Mandylion Or the Story of a Man-Made Relic © by Sébastien Cataldo in Collaboration with Yannick Clément [email protected]

The Mandylion Or The Story Of A Man-Made Relic © By Sébastien Cataldo In Collaboration with Yannick Clément [email protected] www.linceul-turin.com SHROUD OF TURIN The Controversial Intersection of Faith and Science - International Conference St. Louis, Missouri - October 9 - 12, 2014 1 Introduction For many years, numerous historians have tried using historical documents to trace the Shroud of Turin back before its appearance in Lirey, France, around 1357. On this subject, an hypothesis has keep attention, the one proposed by Ian Wilson in 1978. Wilson propose that the portrait of Christ that appeared in the city of Edessa would have been the Shroud of Turin folded in such a way that only the face was visible. This image was venerated in Edessa as a miraculous image of the face of Christ. Then, after its arrival in Constantinople in 944, a very limited number of « priviledged persons » would have discovered its real nature of a burial shroud that bears a bloody and complete body image of Jesus. Later, again in Constantinople, the cloth would have been unfolded and exposed as the real shroud of Christ, before disappearing in 1204, during the sack of Constantinople by the latin crusaders. This is the same shroud that would have appeared in Lirey, France, later on. Here’s a picture that shows what the Image of Edessa might have looked like, if the hypothesis of Ian Wilson would be right: The major problem with this hypothesis is that it didn’t take into account the evolution of the Abgar legend, which is strongly related to the different political and religious context of each era. -

Against the Shroud. but with Mixed Cards

Against the Shroud. But with mixed cards Translation of Contro la Sindone. Ma a carte truccate, Storia in Rete n. 117-118 – July/August 2015 – pp. 28-38 Historian Andrea Nicolotti expects to make a clean sweep of all the «legends» that came out around the Sacred Linen of Turin: a thorough lie that is to be unmasked once and for all using the weapons of historic research. It is a pity that among those weapons there should not be some things that, on the contrary, Nicolotti uses very much: sarcasm and contempt towards who does not think in the same way he does (the reviled «Shroud scholars»), ignored sources and opposite sign research, rash incursions in distant fields, as the science ones. In short, the classical «thesis book», obviously flattered by the major newspapers, that a well- known Shroud scholar read for «Storia in Rete» Emanuela Marinelli «Sutor, ne ultra crepidam!» It is told that this sentence (shoemaker, do not make more than sandals!) was pronounced by Greek painter Apelles of Coo (4th century B.C.). The artist exposed his works at the entrance of his workshop, to keep account of the possible suggestions of the people passing by; so then a shoemaker found that the sandals of a character were depicted in the wrong way, and Apelles hurried up to fix them. The following day the shoemaker, become proud by the acceptance of his previous affirmation, launched into a critic of other details of the picture and at that point Apelles addressed him with the sentence that later became a proverb. -

The Turin Shroud Secret Free

FREE THE TURIN SHROUD SECRET PDF Sam Christer | 512 pages | 02 Feb 2012 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780751547146 | English | London, United Kingdom The Shroud and the Resurrection - The Southern Cross The greatest question remains around how the Shroud was formed. But other questions abound. And not least, the darkest secret of all. How the Shroud itself undermines the Christian Gospel. It is a rectangular cloth, 4. It bears an almost indistinguishable sepia coloured frontal and rear human image on its length. Pia was amazed by the clear image the negative plate revealed in his darkroom demonstrating that the image on the shroud was in fact formed in the negative. Stains found on the cloth were reported to have contained whole blood and conform to the sort of wounds consistent with crucifixion. That this occurred after the death of the victim is demonstrated by the separate components of red blood cells and serum draining from the lesion. There is a deep puncture in the wrist of the uppermost hand. The second wrist is covered. In tests by a team of American scientists known as STURP found no reliable evidence of forgery but were unable to explain the how the image might have been formed. In the Roman Catholic Church agreed to a carbon dating test under strictly monitored conditions. All three reached the same conclusion that the The Turin Shroud Secret could be dated between AD and AD and could therefore not be the the cloth on which Jesus Christ was laid. Since this time, several articles from scholarly sources have stated that the samples used may not have been representative of the whole Shroud. -

Das Turiner Grabtuch. Faszination Und Provokation Eines Außergewöhnlichen Gegenstandes

Das Turiner Grabtuch. Faszination und Provokation eines außergewöhnlichen Gegenstandes. MASTERARBEIT zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades „Master of Arts“(M.A.) an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz eingereicht von Maria Stefania Gabrielli bei Univ.-Prof. Dr. Bernhard Körner Institut für Dogmatik an der Kath.-Theol. Fakultät der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz Graz 2016 Inhalt Vorwort ....................................................................................................................................................5 Einleitung: Zwischen Geschichte, Glaube und Vernunft .........................................................................8 1 Fakten und Legenden eines Rätsels ...............................................................................................12 1.1 Die offizielle Geschichte ........................................................................................................12 1.1.1 Die ersten Spuren .......................................................................................................... 12 1.1.2 Im Haus Savoyen .......................................................................................................... 13 1.1.3 Eine neue Heimat in Turin ............................................................................................ 16 1.1.4 Secondo Pia ................................................................................................................... 18 1.1.5 Die Offenbarung der Fotografie ................................................................................... -

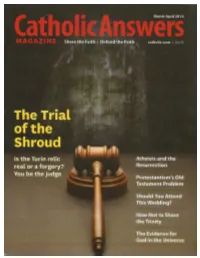

ARTICLE ONLINE at FORUM$.Cathollc.COM

_\_n< \ .. -» » . ~, _ . ,. H N none0u000000oo0~0oooooa4qe0npooc\ooonononopoov00:0 z uncoaunlvboooncnonoconano0005000oouolonolonoaoclon 000ova01000I~l0I00l00I000lc0OIIIl0IUIQIQIQIQQQQQQQ .< *- , DISCUSS THIS ARTICLE ONLINE AT FORUM$.CATHOLlC.COM THE JOURNEY OF THE SHROUD I-I11. FIIIG ‘K-I357 ll?! "Ia L. :I Researchers get their rst look at the shroud of Turin, October 8, 1978. ‘ l "“”‘ A. ,1 4 ' 3 . he Shroud of Turin is an ancient burial cloth ~ ‘W F i ‘ iv C containing the front and back images of a scourged, \" crucied man whom many believe is Iesus Christ. i Ll It is the most-studied artifact in human history. It would The defendant has pleaded not guilty, be hard to disagree with this often-quoted statement: alleging the cloth is a mere curiosity—a worthless fraud. “The Shroud of Turin is either the pose that we determine the issue using After three weeks, the trial reaches most awesome and instructive relic of the jury procedure of a federal criminal closing arguments. Each side seeks to Iesus Christ in existence or it is one of court—and you are the jury. have the jurors recall the evidence most the most ingenious, most unbelievably imagine this hypothetical scenario: favorable to its position. The prosecution clever products of the human mind and The Shroud of Turin is stolen from its carries the heaviest legal burden, since it hand on record. It is one or the other; home in Turin, ltaly, and brought by the must establish the defendant's guilt by es- there is no middle ground" (John Walsh, thief to the United States, where it's re- tablishing the authenticity of the Shroud The Shroud, c. -

Medioevo Greco

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institutional Research Information System University of Turin Medioevo greco Rivista di storia e filologia bizantina 18 (2018) * * Edizioni dell’Orso Alessandria Nuovi studi sulle immagini di Cristo, fra Oriente e Occidente Nell’ottobre 2014 presso l’Istituto della Chiesa Orientale della Facoltà di Teolo- gia dell’Università di Würzburg si è svolto un convegno dedicato all’origine e allo sviluppo delle immagini di Cristo in Oriente e Occidente. Un secondo congresso sulle tracce del volto di Cristo si è tenuto nel marzo 2015 alla Edith Stein-Haus di Vienna, organizzato dall’Accademia Cattolica della città in collaborazione con il sopracitato Istituto di Würzburg. Entrambi i congressi, collegati fra loro, si devono principalmente all’impegno di Karlheinz Dietz, già professore di storia antica all’U- niversità di Würzburg, con il sostegno di diverse istituzioni religiose. I trentadue contributi dei diversi partecipanti ai due convegni (25 in tedesco, 5 in inglese, uno in francese, uno in italiano) sono ora confluiti in un imponente volume di atti, con prefazione di tre vescovi e un cardinale.1 Anche se dal titolo non risulta immediata- mente evidente, l’interesse primario è rivolto alla categoria delle immagini ajceiro- poivhta, cioè quelle che per tradizione sono state considerate miracolose perché «non fatte da mano d’uomo».2 Dirò fin da subito che questo volume merita la massima attenzione per gli argo- menti toccati e per la qualità di diversi contributi, che esaminerò uno ad uno in questa mia nota. Allo stesso tempo, le intenzioni del curatore principale hanno for- temente condizionato larga parte del lavoro secondo una prospettiva a mio parere nefasta. -

Dear John, What Were You Thinking?

An Open Letter to John Dominic Crossan Dear John, What Were You Thinking? In daily life, we assume as certain many things which, on a closer scrutiny, are found to be so full of apparent contradictions that only a great amount of thought enables us to know what it is that we really may believe. In the search for certainty, it is natural to begin with our present experiences, and in some sense, no doubt, knowledge is to be derived from them. But any statement as to what it is that our immediate experiences make us know is very likely to be wrong. ▬ Bertrand Russell, Problems of Philosophy ear Dom: Not long ago, on an Internet forum, someone asked you about the Shroud D of Turin. When I read your answer, my first reaction was amazement. I might have thought that you answered carelessly were it not for two things: Your answer echoed, almost word for word, something you said in a television documentary. And, your analyses and historical reconstructions are always meticulously researched, complex and organized. – even as disturbing as some of them may be, as when you posit that Jesus was not even buried and possibly eaten by dogs and crows. Thus, I really did wonder (in a non-pejorative sense) what were you thinking. You had written in Beliefnet: Crossan: My best understanding is that the Shroud of Turin is a medieval relic- forgery. I wonder whether it was done from a crucified dead body or from a crucified living body. That is the rather horrible question once you accept it as a forgery.