Arxiv:1910.11294V2 [Quant-Ph] 1 Nov 2019 [25, 26] and Give Dominant Impact to the Nonlinear Re- Excitons [60]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pioneering Project Research Activity Report 新領域開拓課題 研究業績報告書

Pioneering Project Research Activity Report 新領域開拓課題 研究業績報告書 Fundamental Principles Underlying the Hierarchy of Matter 物質階層原理 Lead Researcher: Reizo KATO 研究代表者:加藤 礼三 From April 2017 to March 2020 Heterogeneity at Materials Interfaces ヘテロ界面 Lead Researcher: Yousoo Kim 研究代表者:金 有洙 From April 2018 to March 2020 RIKEN May 2020 Contents I. Outline 1 II. Research Achievements and Future Prospects 65 III. Research Highlights 85 IV. Reference Data 139 Outline -1- / Outline of two projects Fundamental Principles Underlying the Hierarchy of Matter: A Comprehensive Experimental Study / • Outline of the Project This five-year project lead by Dr. R. Kato is the collaborative effort of eight laboratories, in which we treat the hierarchy of matter from hadrons to biomolecules with three underlying and interconnected key concepts: interaction, excitation, and heterogeneity. The project consists of experimental research conducted using cutting-edge technologies, including lasers, signal processing and data acquisition, and particle beams at RIKEN RI Beam Factory (RIBF) and RIKEN Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (RAL). • Physical and chemical views of matter lead to major discoveries Although this project is based on the physics and chemistry of non-living systems, we constantly keep all types of matter, including living matter, in our mind. The importance of analyzing matter from physical and chemical points of view was demonstrated in the case of DNA. The Watson-Crick model of DNA was developed based on the X-ray diffraction, which is a physical measurement. The key feature of this model is the hydrogen bonding that occurs between DNA base pairs. Watson and Crick learned about hydrogen bonding in the renowned book “The Nature of the Chemical Bond,” written by their competitor, L. -

Revealing the Exciton Fine Structure in Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals

nanomaterials Review Revealing the Exciton Fine Structure in Lead Halide Perovskite Nanocrystals Lei Hou 1,2 , Philippe Tamarat 1,2 and Brahim Lounis 1,2,* 1 Université de Bordeaux, LP2N, F-33405 Talence, France; [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (P.T.) 2 Institut d’Optique and CNRS, LP2N, F-33405 Talence, France * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Lead-halide perovskite nanocrystals (NCs) are attractive nano-building blocks for photo- voltaics and optoelectronic devices as well as quantum light sources. Such developments require a better knowledge of the fundamental electronic and optical properties of the band-edge exciton, whose fine structure has long been debated. In this review, we give an overview of recent magneto- optical spectroscopic studies revealing the entire excitonic fine structure and relaxation mechanisms in these materials, using a single-NC approach to get rid of their inhomogeneities in morphology and crystal structure. We highlight the prominent role of the electron-hole exchange interaction in the order and splitting of the bright triplet and dark singlet exciton sublevels and discuss the effects of size, shape anisotropy and dielectric screening on the fine structure. The spectral and temporal manifestations of thermal mixing between bright and dark excitons allows extracting the specific nature and strength of the exciton–phonon coupling, which provides an explanation for their remarkably bright photoluminescence at low temperature although the ground exciton state is optically inactive. We also decipher the spectroscopic characteristics of other charge complexes Citation: Hou, L.; Tamarat, P.; whose recombination contributes to photoluminescence. With the rich knowledge gained from these Lounis, B. -

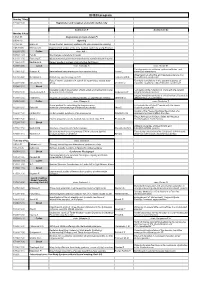

EFB23 Program Sunday 7/Aug

EFB23 program Sunday 7/Aug. 17:00-19:00 Registration and reception at Scandic Aarhus City Auditorium F Auditorium G2 Monday 8/Aug. 8:30-8:55 Registration (in front of Aud. F) 9:00-9:10 Opening 9:10-9:45 Blume D. A new frontier: Few-body systems with spin-momentum coupling 9:45-10:20 Shimoura S. Experimental studies of the tetra-neutron system by using RI-beam 10:20-10:50 Coffee chair: Arlt J. 10:50-11:23 Hen O. Short-range correlations in nuclei 11:23-11:56 Piasetzky E. Measurement of polarization transfered to a proton bound in nuclei 11:56-12:30 Epelbaum E. Recent results in nuclear chiral effective field theory 12:30-14:00 Lunch chair: Kamada H. chair: Viviani M. Faraday waves in coldatom systems with two- and 14:00-14:20 Riisager K. Beta-delayed particle emission from neutron halos Tomio L. three-body interactions Observation of attractive and repulsive polarons in a 14:20-14:40 Refsgaard J. Beta-decay spectroscopy on 12C Jorgensen N.B. Bose-Einstein condensate Role of atomic excitations in search for neutrinoless double beta- Few-body correlations in the spectral response of 14:40-15:00 Amusia M.Ya. decay Levinsen J. impurities coupled to a Bose-Einstein condensate 15:00-15:10 Break Unstable nuclei in dissociation of light stable and radioactive nuclei Calculation of the S-factor $S_{12}$ with the Lorentz 15:10-15:30 Artemenkov D.A. in nuclear track emulsion Leidemann W. integral transform method Integral transform methods: a critical review of kernels for 15:30-15:50 Feldman G. -

Layer Locking Effects in Optical Orientation of Exciton Spin in Bilayer Wse2

LETTERS PUBLISHED ONLINE: 5 JANUARY 2014 | DOI: 10.1038/NPHYS2848 Spin–layer locking effects in optical orientation of exciton spin in bilayer WSe2 Aaron M. Jones1, Hongyi Yu2, Jason S. Ross3, Philip Klement1,4, Nirmal J. Ghimire5,6, Jiaqiang Yan6,7, David G. Mandrus5,6,7, Wang Yao2 and Xiaodong Xu1,3* Coupling degrees of freedom of distinct nature plays a pseudospin up or down, respectively, which corresponds to electri- critical role in numerous physical phenomena1–10. The recent cal polarization. In a layered material with spin–valley coupling and emergence of layered materials11–13 provides a laboratory for AB stacking, such as bilayer TMDCs, both spin and valley are cou- studying the interplay between internal quantum degrees pled to layer pseudospin15. As shown in Fig. 1a, because the lower of freedom of electrons14,15. Here we report new coupling layer is a 180◦ in-plane rotation of the upper layer, the out-of-plane phenomena connecting real spin with layer pseudospins spin splitting has a sign that depends on both valley and layer pseu- in bilayer WSe2. In polarization-resolved photoluminescence dospins. Interlayer hopping thus has an energy cost equal to twice measurements, we observe large spin orientation of neutral the SOC strength λ. When 2λ is larger than the hopping amplitude and charged excitons by both circularly and linearly polarized t?, a carrier is localized in either the upper or lower layer depending excitation, with the trion spectrum splitting into a doublet on its valley and spin state. In other words, in a given valley, the at large vertical electrical field. -

A) Spin-Photon Correlations in Solid-State Systems

A) Spin-photon correlations in solid-state systems A. Imamoglu Quantum Photonics Group, Department of Physics ETH-Zürich Solid-state spins & emitters • Solid-state emitters (artificial atoms) can be used to realize high brightness long-lived single-photon sources: - no need for trapping - easy integration into a directional (fiber-coupled) cavity - up to 109 photons/sec with >70% efficiency • Three different classes of emitters: - rare-earth atoms embedded in a solid matrix (Er in glass) - Deep defects in insulators (NV centers in diamond) - Shallow defects in semiconductors (quantum dots) Note: While the concepts & techniques apply to a wide range of solid-state emitters, we focus on quantum dots Quantum dots & single photons A quantum dot (QD), is a mesoscopic semiconductor structure (~10nm confinement length-scale) consisting of 10,000 atoms and still having a discrete (anharmonic) optical excitation spectrum. -MBE grown InGaAs quantum dot -QDs in monolayer WSe2 Light generation by a quantum dot Resonant laser excitation - Laser excitation - - - - - Light generation by a quantum dot Resonant laser excitation - - Laser excitation - + - - - - electron-hole pair = exciton Light generation by a quantum dot Resonant laser excitation Resonance fluorescence 12000 9000 photon 6000 1X emission 3000 RF (counts/s) 0 - - -20 -10 0 10 20 - - Energy detuning (µeV) - - Quantum dot Spectroscopy From laser Polarization filter To detector Polarization optics NA=0.65 Spot size ≈1µm Magnet Piezo positioner GaAs InGaAs Liquid He GaAs Photon correlations from a single QD (2) : I(t)I(t ) : • Intensity (photon) correlation function: g ( ) 2 I(t) stop pulse • To measure g(2)(), photons from a quantum emitter are single photon detectors sent to a Hanbury-Brown Time-to- Twiss setup amplitude start (voltage) pulse converter • Single quantum emitter driven by a pulsed laser: absence of a center peak indicates that none of the pulses have > 1 photon (Robert, LPN). -

Spin Transport in a Quantum Hall Insulator

applied sciences Article Spin Transport in a Quantum Hall Insulator Azaliya Azatovna Zagitova 1,*, Andrey Sergeevich Zhuravlev 1, Leonid Viktorovich Kulik 1 and Vladimir Umansky 2 1 Institute of Solid State Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, 142432 Chernogolovka, Russia; [email protected] (A.S.Z.); [email protected] (L.V.K.) 2 Braun Center for Submicron Research, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A novel experimental optical method, based on photoluminescence and photo-induced resonant reflection techniques, is used to investigate the spin transport over long distances in a new, recently discovered collective state—magnetofermionic condensate. The given Bose–Einstein condensate exists in a purely fermionic system (ν = 2 quantum Hall insulator) due to the presence of a non-equilibrium ensemble of spin-triplet magnetoexcitons—composite bosons. It is found that the condensate can spread over macroscopically long distances of approximately 200 µm. The propagation velocity of long-lived spin excitations is measured to be 25 m/s. Keywords: spintronics; spin transport; excitations; low-dimensional systems; spectroscopy; the Bose–Einstein condensate 1. Introduction The growing interest in spintronics [1,2] has been incited by the prospect of build- Citation: Zagitova, A.A.; Zhuravlev, ing fast, energy-efficient devices utilizing the electron spin. In particular, there has been A.S.; Kulik, L.V.; Umansky, V. Spin rapid development in magnonics [3], which uses spin waves to transport information [4,5]. Transport in a Quantum Hall Magnonic systems are free of many disadvantages of electronic systems associated with Insulator. -

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title MEASUREMENTS OP THE MUON-CAPTURE RATE IN He3 AND He4 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0wd1f3t9 Author Easterling, Robert John. Publication Date 1964-04-09 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UCRL-11004 c.~ .. University of California Ernest 0. lawrence Radiation laboratory TWO-WEEK LOAN COPY This is a library Circulating Copy which may be borrowed for two weeks. For a personal retention copy, call Tech. Info. Dioision, Ext. 5545 MEASUREMENTS OF THE MUON-CAPTURE RATE IN He3 AND He 4 Berkeley. California DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. UCRL-11004 .... UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Lawrence Radiation Laboratory Berkeley, California • AEC Contract No. -

Exciton-Polarons in Doped Semiconductors in a Strong Magnetic Field

PHYSICAL REVIEW B 97, 235432 (2018) Exciton-polarons in doped semiconductors in a strong magnetic field Dmitry K. Efimkin and Allan H. MacDonald Center for Complex Quantum Systems, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78712, USA (Received 19 July 2017; revised manuscript received 9 April 2018; published 21 June 2018) In previous work, we have argued that the optical properties of moderately doped two-dimensional semi- conductors can be described in terms of excitons dressed by their interactions with a degenerate Fermi sea of additional charge carriers. These interactions split the bare exciton into attractive and repulsive exciton-polaron branches. The collective excitations of the coupled system are many-body generalizations of the bound trion and unbound states of a single electron interacting with an exciton. In this paper, we consider exciton-polarons in the presence of an external magnetic field that quantizes the kinetic energy of the electrons in the Fermi sea. Our theoretical approach is based on a transformation to a new basis that respects the underlaying symmetry of magnetic translations. We find that the attractive exciton-polaron branch is only weakly influenced by the magnetic field, whereas the repulsive branch exhibits magnetic oscillations and splits into discrete peaks that reflect combined exciton-cyclotron resonance. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevB.97.235432 I. INTRODUCTION dress excitons into exciton-polarons. Exciton-polarons have attractive and repulsive spectral branches that evolve from The monolayer transition metal dicholagenides (TMDCs), and generalize to degenerate carrier densities, the separate MoS , MoSe ,WS, and WSe , are widely studied 2 2 2 2 absorption processes associated with bound and unbound trion in beyond-graphene [1–3] two-dimensional semiconductors states. -

Arxiv:2105.04327V2

Valley polarization of trions in monolayer MoSe2 interfaced with bismuth iron garnet Vasily Kravtsov,1, ∗ Tatiana Ivanova,1 Artem N. Abramov,1 Polina V. Shilina,2 Pavel O. Kapralov,3 Dmitry N. Krizhanovskii,1, 4 Vladimir N. Berzhansky,5 Vladimir I. Belotelov,3, 5, 6 Ivan A. Shelykh,7, 1 Alexander I. Chernov,2, 3, 8 and Ivan V. Iorsh1, † 1Department of Physics and Engineering, ITMO University, Saint Petersburg 197101, Russia 2Center for Photonics and 2D Materials, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, National Research University, Dolgoprudny 141700, Russia 3Russian Quantum Center, Skolkovo Innovation City, Moscow 121353, Russia 4Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S3 7RH, UK 5Vernadsky Crimean Federal University, Simferopol 295007, Russia 6Faculty of Physics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow 119991, Russia 7Science Institute, University of Iceland, Dunhagi-3, IS-107 Reykjavik, Iceland 8NTI Center for Quantum Communications, National University of Science and Technology MISiS, Moscow 125009, Russia (Dated: July 2, 2021) Interfacing atomically thin van der Waals semiconductors with magnetic substrates enables additional control on their intrinsic valley degree of freedom and provides a promising platform for the development of novel valleytronic devices for informa- tion processing and storage. Here we study circularly polarized photoluminescence in heterostructures of monolayer MoSe2 and thin films of ferrimagnetic bismuth iron garnet. We observe strong emission from charged excitons with negative -

Dynamics of Charged Excitons in Electronically and Morphologically Homogeneous Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes

Dynamics of charged excitons in electronically and morphologically homogeneous single-walled carbon nanotubes Yusong Baia, Jean-Hubert Oliviera, George Bullarda, Chaoren Liua, and Michael J. Theriena,1 aDepartment of Chemistry, French Family Science Center, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708-0346 Edited by José N. Onuchic, Rice University, Houston, TX, and approved December 8, 2017 (received for review July 22, 2017) The trion, a three-body charge-exciton bound state, offers unique SWNTs demonstrate a new lower-energy absorption, which opportunities to simultaneously manipulate charge, spin, and has been attributed to a direct ground-to-trion optical tran- + hυ + + excitation in one-dimensional single-walled carbon nanotubes sition (E 00 ! Tr 11, where Tr 11 denotes a low-lying elec- (SWNTs) at room temperature. Effective exploitation of trion tronically excited trion state) (5, 8); no experimental evidence, quasi-particles requires fundamental insight into their creation however, has confirmed the nature of the state produced by and decay dynamics. Such knowledge, however, remains elusive + SWNT E photon absorption. for SWNT trion states, due to the electronic and morphological 00 Here, we describe the transient absorptive and dynamical heterogeneity of commonly interrogated SWNT samples, and the properties of hole trions in length-sorted semiconducting (6,5) fact that transient spectroscopic signals uniquely associated with the trion state have not been identified. Here, we prepare length- SWNTs, wherein hole polaron densities are rigorously con- sorted SWNTs and precisely control charge-carrier-doping densi- trolled. Owing to the electronic and morphological homogeneity ties to determine trion dynamics using femtosecond pump–probe of these SWNT samples, we clearly identify a trion transient spectroscopy. -

The Interplay Between Excitons and Trions in a Monolayer of Mose 2 N

The interplay between excitons and trions in a monolayer of MoSe 2 N. Lundt, E. Cherotchenko, O. Iff, X. Fan, Y. Shen, Pierre Bigenwald, A. Kavokin, S. Höfling, C. Schneider To cite this version: N. Lundt, E. Cherotchenko, O. Iff, X. Fan, Y. Shen, et al.. The interplay between excitons andtrions in a monolayer of MoSe 2. Applied Physics Letters, American Institute of Physics, 2018, 112 (3), 10.1063/1.5019177. hal-01920345 HAL Id: hal-01920345 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01920345 Submitted on 14 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License The interplay between excitons and trions in a monolayer of MoSe2 Cite as: Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 031107 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5019177 Submitted: 19 May 2017 . Accepted: 11 December 2017 . Published Online: 17 January 2018 N. Lundt, E. Cherotchenko, O. Iff, X. Fan, Y. Shen, P. Bigenwald, A. V. Kavokin , S. Höfling, and C. Schneider ARTICLES YOU MAY BE INTERESTED IN Broadband nonlinear optical response of monolayer MoSe2 under ultrafast excitation Applied Physics Letters 112, 031108 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5010060 Giant excitation induced bandgap renormalization in TMDC monolayers Applied Physics Letters 112, 061104 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5017069 Topological optical isolator based on polariton graphene Applied Physics Letters 112, 031106 (2018); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5018902 Appl. -

FROM FLASKS to APPLICATIONS: DESIGN and OPTIMIZATION of GIANT QUANTUM DOTS USING TRADITIONAL and AUTOMATED SYNTHETIC METHODS Christina J

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Nanoscience and Microsystems ETDs Engineering ETDs Spring 4-12-2018 FROM FLASKS TO APPLICATIONS: DESIGN AND OPTIMIZATION OF GIANT QUANTUM DOTS USING TRADITIONAL AND AUTOMATED SYNTHETIC METHODS Christina J. Hanson University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nsms_etds Part of the Inorganic Chemistry Commons, Materials Chemistry Commons, Nanoscience and Nanotechnology Commons, Physical Chemistry Commons, and the Semiconductor and Optical Materials Commons Recommended Citation Hanson, Christina J.. "FROM FLASKS TO APPLICATIONS: DESIGN AND OPTIMIZATION OF GIANT QUANTUM DOTS USING TRADITIONAL AND AUTOMATED SYNTHETIC METHODS." (2018). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nsms_etds/ 45 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Engineering ETDs at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nanoscience and Microsystems ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Christina J. Hanson Candidate Nanoscience and Microsystems Engineering Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Prof. John K. Grey, Chairperson Dr. Jennifer A. Hollingsworth Dr. Han. Htoon Prof. Diane S. Lidke Prof. Andrew P. Shreve i FROM FLASKS TO APPLICATIONS: DESIGN AND OPTIMIZATION OF GIANT QUANTUM DOTS USING TRADITIONAL AND AUTOMATED SYNTHETIC METHODS BY CHRISTINA J. HANSON B.S.,