Short-Term Outcomes of COVID-19 and Risk Factors for Progression

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society Heather Langford Theses submitted for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Centre of Asian Studies University of Adelaide May 2009 ii Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the research requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Centre of Asian Studies School of Humanities and Social Sciences Adelaide University 2009 iii Table of Contents 1. Introduction.........................................................................................1 1.1. Literature Review..............................................................................13 1.2. Chapter summary ..............................................................................17 1.3. Conclusion ........................................................................................19 2. Background .......................................................................................20 2.1. Pre Han History.................................................................................20 2.2. Qin Dynasty ......................................................................................24 2.3. The Han Dynasty...............................................................................25 2.3.1. Trade with the West............................................................................. 30 2.4. Conclusion ........................................................................................32 3. Textiles and Technology....................................................................33 -

Ps TOILETRY CASE SETS ACROSS LIFE and DEATH in EARLY CHINA (5 C. BCE-3 C. CE) by Sheri A. Lullo BA, University of Chicago

TOILETRY CASE SETS ACROSS LIFE AND DEATH IN EARLY CHINA (5th c. BCE-3rd c. CE) by Sheri A. Lullo BA, University of Chicago, 1999 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts & Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2009 Ps UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS & SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Sheri A. Lullo It was defended on October 9, 2009 and approved by Anthony Barbieri-Low, Associate Professor, History Dept., UC Santa Barbara Karen M. Gerhart, Professor, History of Art and Architecture Bryan K. Hanks, Associate Professor, Anthropology Anne Weis, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Katheryn M. Linduff, Professor, History of Art and Architecture ii Copyright © by Sheri A. Lullo 2009 iii TOILETRY CASE SETS ACROSS LIFE AND DEATH IN EARLY CHINA (5th c. BCE-3rd c. CE) Sheri A. Lullo, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 This dissertation is an exploration of the cultural biography of toiletry case sets in early China. It traces the multiple significances that toiletry items accrued as they moved from contexts of everyday life to those of ritualized death, and focuses on the Late Warring States Period (5th c. BCE) through the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE), when they first appeared in burials. Toiletry case sets are painted or inlaid lacquered boxes that were filled with a variety of tools for beautification, including combs, mirrors, cosmetic substances, tweezers, hairpins and a selection of personal items. Often overlooked as ordinary, non-ritual items placed in burials to comfort the deceased, these sets have received little scholarly attention beyond what they reveal about innovations in lacquer technologies. -

Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin

Journal of chinese humanities 5 (2019) 124-148 brill.com/joch Imagining a Universal Empire: a Study of the Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions Attributed to Li Gonglin Ge Zhaoguang 葛兆光 Professor of History, Fudan University, China [email protected] Abstract This article is not concerned with the history of aesthetics but, rather, is an exercise in intellectual history. “Illustrations of Tributary States” [Zhigong tu 職貢圖] as a type of art reveals a Chinese tradition of artistic representations of foreign emissaries paying tribute at the imperial court. This tradition is usually seen as going back to the “Illustrations of Tributary States,” painted by Emperor Yuan in the Liang dynasty 梁元帝 [r. 552-554] in the first half of the sixth century. This series of paintings not only had a lasting influence on aesthetic history but also gave rise to a highly distinctive intellectual tradition in the development of Chinese thought: images of foreign emis- saries were used to convey the Celestial Empire’s sense of pride and self-confidence, with representations of strange customs from foreign countries serving as a foil for the image of China as a radiant universal empire at the center of the world. The tra- dition of “Illustrations of Tributary States” was still very much alive during the time of the Song dynasty [960-1279], when China had to compete with equally powerful neighboring states, the empire’s territory had been significantly diminished, and the Chinese population had become ethnically more homogeneous. In this article, the “Illustrations of the Tributary States of the Myriad Regions” [Wanfang zhigong tu 萬方職貢圖] attributed to Li Gonglin 李公麟 [ca. -

Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China

Entropy 2014, 16, 6313-6337; doi:10.3390/e16126313 OPEN ACCESS entropy ISSN 1099-4300 www.mdpi.com/journal/entropy Article Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China Xixi Chen 1, Tao Hu 1, Fu Ren 1,2,*, Deng Chen 1, Lan Li 1 and Nan Gao 1 1 School of Resource and Environment Science, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China; E-Mails: [email protected] (X.C.); [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (L.L.); [email protected] (N.G.) 2 Key Laboratory of Geographical Information System, Ministry of Education, Wuhan University, Luoyu Road 129, Wuhan 430079, China * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel: +86-27-87664557; Fax: +86-27-68778893. External Editor: Hwa-Lung Yu Received: 20 July 2014; in revised form: 31 October 2014 / Accepted: 26 November 2014 / Published: 1 December 2014 Abstract: Hubei Province is the hub of communications in central China, which directly determines its strategic position in the country’s development. Additionally, Hubei Province is well-known for its diverse landforms, including mountains, hills, mounds and plains. This area is called “The Province of Thousand Lakes” due to the abundance of water resources. Geographical names are exclusive names given to physical or anthropogenic geographic entities at specific spatial locations and are important signs by which humans understand natural and human activities. In this study, geographic information systems (GIS) technology is adopted to establish a geodatabase of geographical names with particular characteristics in Hubei Province and extract certain geomorphologic and environmental factors. -

Download Article

Advances in Economics, Business and Management Research, volume 70 International Conference on Economy, Management and Entrepreneurship(ICOEME 2018) Research on the Path of Deep Fusion and Integration Development of Wuhan and Ezhou Lijiang Zhao Chengxiu Teng School of Public Administration School of Public Administration Zhongnan University of Economics and Law Zhongnan University of Economics and Law Wuhan, China 430073 Wuhan, China 430073 Abstract—The integration development of Wuhan and urban integration of Wuhan and Hubei, rely on and Ezhou is a strategic task in Hubei Province. It is of great undertake Wuhan. Ezhou City takes the initiative to revise significance to enhance the primacy of provincial capital, form the overall urban and rural plan. Ezhou’s transportation a new pattern of productivity allocation, drive the development infrastructure is connected to the traffic artery of Wuhan in of provincial economy and upgrade the competitiveness of an all-around and three-dimensional way. At present, there provincial-level administrative regions. This paper discusses are 3 interconnected expressways including Shanghai- the path of deep integration development of Wuhan and Ezhou Chengdu expressway, Wuhan-Ezhou expressway and from the aspects of history, geography, politics and economy, Wugang expressway. In terms of market access, Wuhan East and puts forward some suggestions on relevant management Lake Development Zone and Ezhou Gedian Development principles and policies. Zone try out market access cooperation, and enterprises Keywords—urban regional cooperation; integration registered in Ezhou can be named with “Wuhan”. development; path III. THE SPACE FOR IMPROVEMENT IN THE INTEGRATION I. INTRODUCTION DEVELOPMENT OF WUHAN AND EZHOU Exploring the path of leapfrog development in inland The degree of integration development of Wuhan and areas is a common issue for the vast areas (that is to say, 500 Ezhou is lower than that of central urban area of Wuhan, and kilometers from the coastline) of China’s hinterland. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 6, 2016 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 21–471 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:58 Oct 05, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\AR16 NEW\21471.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Cochairman Chairman JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina TOM COTTON, Arkansas TRENT FRANKS, Arizona STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois BEN SASSE, Nebraska DIANE BLACK, Tennessee DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio GARY PETERS, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California TED LIEU, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS CHRISTOPHER P. LU, Department of Labor SARAH SEWALL, Department of State DANIEL R. RUSSEL, Department of State TOM MALINOWSKI, Department of State PAUL B. PROTIC, Staff Director ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:58 Oct 05, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\AR16 NEW\21471.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 Overview ............................................................................................................ 5 Recommendations to Congress and the Administration .............................. -

Present Status, Driving Forces and Pattern Optimization of Territory in Hubei Province, China Tingke Wu, Man Yuan

World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Environmental and Ecological Engineering Vol:13, No:5, 2019 Present Status, Driving Forces and Pattern Optimization of Territory in Hubei Province, China Tingke Wu, Man Yuan market failure [4]. In fact, spatial planning system of China is Abstract—“National Territorial Planning (2016-2030)” was not perfect. It is a crucial problem that land resources have been issued by the State Council of China in 2017. As an important unordered and decentralized developed and overexploited so initiative of putting it into effect, territorial planning at provincial level that ecological space and agricultural space are seriously makes overall arrangement of territorial development, resources and squeezed. In this regard, territorial planning makes crucial environment protection, comprehensive renovation and security system construction. Hubei province, as the pivot of the “Rise of attempt to realize the "Multi-Plan Integration" mode and Central China” national strategy, is now confronted with great contributes to spatial planning system reform. It is also opportunities and challenges in territorial development, protection, conducive to improving land use regulation and enhancing and renovation. Territorial spatial pattern experiences long time territorial spatial governance ability. evolution, influenced by multiple internal and external driving forces. Territorial spatial pattern is the result of land use conversion It is not clear what are the main causes of its formation and what are for a long period. Land use change, as the significant effective ways of optimizing it. By analyzing land use data in 2016, this paper reveals present status of territory in Hubei. Combined with manifestation of human activities’ impact on natural economic and social data and construction information, driving forces ecosystems, has always been a specific field of global climate of territorial spatial pattern are then analyzed. -

Are China's Water Resources for Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence from Hubei Province

sustainability Article Are China’s Water Resources for Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence from Hubei Province Hao Jin and Shuai Huang * School of Public Economics and Administration, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, Shanghai 200433, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-21-65903686 Abstract: We assessed the sustainability of agricultural water resources in Hubei Province, a typical agricultural province in central China, for a decade (2008–2018). Since traditional evaluation models often consider only the distance between the evaluation point and the positive or negative ideal solution, we introduce gray correlation analysis and construct a new sustainability evaluation model. Our research results show that only one city had excellent sustainable development capacity of agricultural water resources, and the evaluation value of eight cities fluctuated by around 0.5 (the median of the evaluation result), while the sustainable development capacity of agricultural water resources in other cities was relatively poor. Our findings not only reflect the differences in the natural conditions of water resources among various cities in Hubei, but also the impact of the cities’ policies to ensure efficient agricultural water use for sustainable development. The indicators and methods Citation: Jin, H.; Huang, S. Are in this research are not difficult to obtain in most countries and regions of the world. Therefore, the China’s Water Resources for indicator system we have established by this research could be used to study the sustainability of Agriculture Sustainable? Evidence agricultural water resources in other countries, regions, or cities. from Hubei Province. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3510. https://doi.org/ Keywords: water resources; agricultural water resources; sustainability; gray correlation analysis; 10.3390/su13063510 evaluation model Academic Editors: Daniela Malcangio, Alan Cuthbertson, Juan 1. -

Study on the Relationship Between Guan Yu and Sun Quan (The Kingdom of Wu)

2019 International Conference on Cultural Studies, Tourism and Social Sciences (CSTSS 2019) Study on the Relationship between Guan Yu and Sun Quan (The Kingdom of Wu) Xinzhao Tang School of History and Culture, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China Keywords: Guan Yu; Sun Quan and the kingdom of Wu; Jingzhou Abstract: The alliance formation of Sun Quan and Liu Bei makes China's political structure gradually enter the “three kingdoms” era in the late Eastern Han Dynasty. After the battle of Red Cliff, the alliance gradually breaks down. Many scholars pass the buck to Guan Yu. They think that the reason why the alliance of Sun Quan and Liu Bei broke down at last is because Guan Yu was too headstrong and he didn’t pay much attention to better the relationship with Sun Quan. This paper discusses the breakdown of the alliance of Sun Quan and Liu Bei from Guan Yu's point of view. 1. Introduction The formation of the alliance of Sun Quan and Liu Bei is the result of the change of the political pattern since the late Eastern Han Dynasty. The powerful warlords destroyed the weak warlords, and the weak warlords had to form an alliance to fight against the powerful warlords for their survival. As Cao Cao and his army were marching toward the south, Sun Quan and Liu Bei formed an alliance and defeated Cao Cao in the battle of Red Cliff. After that, with the threat of Cao Cao gradually decreasing, the contradiction between the two forces began to become increasingly sharp. -

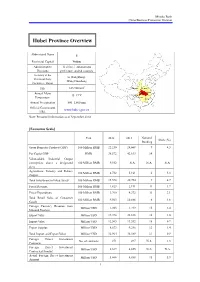

Hubei Province Overview

Mizuho Bank China Business Promotion Division Hubei Province Overview Abbreviated Name E Provincial Capital Wuhan Administrative 12 cities, 1 autonomous Divisions prefecture, and 64 counties Secretary of the Li Hongzhong; Provincial Party Wang Guosheng Committee; Mayor 2 Size 185,900 km Shaanxi Henan Annual Mean Hubei Anhui 15–17°C Chongqing Temperature Hunan Jiangxi Annual Precipitation 800–1,600 mm Official Government www.hubei.gov.cn URL Note: Personnel information as of September 2014 [Economic Scale] Unit 2012 2013 National Share (%) Ranking Gross Domestic Product (GDP) 100 Million RMB 22,250 24,668 9 4.3 Per Capita GDP RMB 38,572 42,613 14 - Value-added Industrial Output (enterprises above a designated 100 Million RMB 9,552 N.A. N.A. N.A. size) Agriculture, Forestry and Fishery 100 Million RMB 4,732 5,161 6 5.3 Output Total Investment in Fixed Assets 100 Million RMB 15,578 20,754 9 4.7 Fiscal Revenue 100 Million RMB 1,823 2,191 11 1.7 Fiscal Expenditure 100 Million RMB 3,760 4,372 11 3.1 Total Retail Sales of Consumer 100 Million RMB 9,563 10,886 6 4.6 Goods Foreign Currency Revenue from Million USD 1,203 1,219 15 2.4 Inbound Tourism Export Value Million USD 19,398 22,838 16 1.0 Import Value Million USD 12,565 13,552 18 0.7 Export Surplus Million USD 6,833 9,286 12 1.4 Total Import and Export Value Million USD 31,964 36,389 17 0.9 Foreign Direct Investment No. -

Download Article

International Conference on Education, Management, Computer and Society (EMCS 2016) Basic Research Development of Local Colleges and Universities Transition ——A Case Study of Yangtze University College of Engineering and Technology Liu Changming Yangtze University College of Engineering and Technology Technology Department Jingzhou,China e-mail:[email protected] Abstract- In order to steadily promote school restructuring technology, Yangtze University, for example, do some and development, application of technology to improve the basic questions on the restructuring and development of quality of talents training, school-based research paper uses local research universities. I believe that the basis of the case studies and other methods proposed restructuring and restructuring and development of local colleges and development of local colleges and universities need to study universities, including at least the following aspects. the basic conditions of the proposition, research-based foundation from school conditions, teaching and based on I. BASIC SCHOOL CONDITIONS three aspects of cooperative Education, Yangtze University of Engineering and Technology for the analysis, the Local colleges and universities transformation and conclusion is: Yangtze University College of Engineering and development, the most important is to have a school in line Technology in order to further serve regional economic and with the basic conditions for economic and social social development, service industries and enterprises and development and personnel training needs of the region. technological progress, the ability to enhance the application Therefore, the conditions for school self-assessment is a of technology student services has laid a good foundation the prerequisite for the restructuring and development of basic prerequisite for development with the transition. -

Retrospect: the Outbreak Evaluation of COVID-19 in Wuhan District of China

healthcare Article Retrospect: The Outbreak Evaluation of COVID-19 in Wuhan District of China Yimin Zhou 1,2,*,† , Zuguo Chen 1,3,† , Xiangdong Wu 1,2 , Zengwu Tian 1,2, Lingjian Ye 1,2 and Leyi Zheng 1,2 1 Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1068 Xueyuan Avenue, Xili University Town, Shenzhen 518055, China; [email protected] (Z.C.); [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (Z.T.); [email protected] (L.Y.); [email protected] (L.Z.) 2 School of Computer Science and Technology, The University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 School of Information and Electrical Engineering, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan 411201, China * Correspondence: [email protected] † The first two authors contributed equally. Abstract: There were 27 novel coronavirus pneumonia cases found in Wuhan, China in December 2019, named as 2019-nCoV temporarily and COVID-19 formally by the World Health Organization (WHO) on the 11 February 2020. In December 2019 and January 2020, COVID-19 has spread on a large scale among the population, which brought terrible disaster to the life and property of the Chinese people. In this paper, we analyze the features and pattern of the virus transmission. Considering the influence of indirect transmission, a conscious-based Susceptible-Exposed-Infective-Recovered (SEIR) (C-SEIR) model is proposed, and the difference equation is used to establish the model. We simulated the C-SEIR model and key important parameters. The results show that (1) increasing people’s awareness of the virus can effectively reduce the spread of the virus; (2) as the capability and possibility of indirect infection increases, the proportion of people being infected will also increase; (3) the increased cure rate can effectively reduce the number of infected people.