Impact of the KCNQ2/3 Channel Opener Ezogabine on Reward Circuit Activity and Clinical Symptoms in Depression: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benzodiazepines: Uses and Risks Charlie Reznikoff, MD Hennepin Healthcare

Benzodiazepines: Uses and Risks Charlie Reznikoff, MD Hennepin healthcare 4/22/2020 Overview benzodiazepines • Examples of benzos and benzo like drugs • Indications for benzos • Pharmacology of benzos • Side effects and contraindications • Benzo withdrawal • Benzo tapers 12/06/2018 Sedative/Hypnotics • Benzodiazepines • Alcohol • Z-drugs (Benzo-like sleeping aids) • Barbiturates • GHB • Propofol • Some inhalants • Gabapentin? Pregabalin? 12/06/2018 Examples of benzodiazepines • Midazolam (Versed) • Triazolam (Halcion) • Alprazolam (Xanax) • Lorazepam (Ativan) • Temazepam (Restoril) • Oxazepam (Serax) • Clonazepam (Klonopin) • Diazepam (Valium) • Chlordiazepoxide (Librium) 4/22/2020 Sedatives: gaba stimulating drugs have incomplete “cross tolerance” 12/06/2018 Effects from sedative (Benzo) use • Euphoria/bliss • Suppresses seizures • Amnesia • Muscle relaxation • Clumsiness, visio-spatial impairment • Sleep inducing • Respiratory suppression • Anxiolysis/disinhibition 12/06/2018 Tolerance to benzo effects? • Effects quickly diminish with repeated use (weeks) • Euphoria/bliss • Suppresses seizures • Effects incompletely diminish with repeated use • Amnesia • Muscle relaxation • Clumsiness, visio-spatial impairment • Seep inducing • Durable effects with repeated use • Respiratory suppression • Anxiolysis/disinhibition 12/06/2018 If you understand this pharmacology you can figure out the rest... • Potency • 1 mg diazepam <<< 1 mg alprazolam • Duration of action • Half life differences • Onset of action • Euphoria, clinical utility in acute -

Acute Migraine Treatment

Acute Migraine Treatment Morris Levin, MD Professor of Neurology Director, Headache Center UCSF Department of Neurology San Francisco, CA Mo Levin Disclosures Consulting Royalties Allergan Oxford University Press Supernus Anadem Press Amgen Castle Connolly Med. Publishing Lilly Wiley Blackwell Mo Levin Disclosures Off label uses of medication DHE Antiemetics Zolmitriptan Learning Objectives At the end of the program attendees will be able to 1. List all important options in the acute treatment of migraine 2. Discuss the evidence and guidelines supporting the major migraine acute treatment options 3. Describe potential adverse effects and medication- medication interactions in acute migraine pharmacological treatment Case 27 y/o woman has suffered ever since she can remember from “sick headaches” . Pain is frontal, increases over time and is generally accompanied by nausea and vomiting. She feels depressed. The headache lasts the rest of the day but after sleeping through the night she awakens asymptomatic 1. Diagnosis 2. Severe Headache relief Diagnosis: What do we need to beware of? • Misdiagnosis of primary headache • Secondary causes of headache Red Flags in HA New (recent onset or change in pattern) Effort or Positional Later onset than usual (middle age or later) Meningismus, Febrile AIDS, Cancer or other known Systemic illness - Neurological or psych symptoms or signs Basic principles of Acute Therapy of Headaches • Diagnose properly, including comorbid conditions • Stratify therapy rather than treat in steps • Treat early -

Accurate Measurement, and Validation of Solubility Data † ‡ ‡ § † ‡ Víctor R

Article Cite This: Cryst. Growth Des. 2019, 19, 4101−4108 pubs.acs.org/crystal In the Context of Polymorphism: Accurate Measurement, and Validation of Solubility Data † ‡ ‡ § † ‡ Víctor R. Vazqueź Marrero, , Carmen Piñero Berríos, , Luz De Dios Rodríguez, , ‡ ∥ ‡ § Torsten Stelzer,*, , and Vilmalí Lopez-Mej́ ías*, , † Department of Biology, University of Puerto RicoRío Piedras Campus, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00931, United States ‡ Crystallization Design Institute, Molecular Sciences Research Center, University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00926, United States § Department of Chemistry, University of Puerto RicoRío Piedras Campus, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00931, United States ∥ Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Puerto RicoMedical Sciences Campus, San Juan, Puerto Rico 00936, United States *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: Solubility measurements for polymorphic com- pounds are often accompanied by solvent-mediated phase transformations. In this study, solubility measurements from undersaturated solutions are employed to investigate the solubility of the two most stable polymorphs of flufenamic acid (FFA forms I and III), tolfenamic acid (TA forms I and II), and the only known form of niflumic acid (NA). The solubility was measured from 278.15 to 333.15 K in four alcohols of a homologous series (methanol, ethanol, 1- propanol, n-butanol) using the polythermal method. It was established that the solubility of these compounds increases with increasing temperature. The solubility curves of FFA forms I and III intersect at ∼315.15 K (42 °C) in all four solvents, which represents the transition temperature of the enantiotropic pair. In the case of TA, the solubility of form II could not be reliably obtained in any of the solvents because of the fast solvent- mediated phase transformation. -

S1 Table. List of Medications Analyzed in Present Study Drug

S1 Table. List of medications analyzed in present study Drug class Drugs Propofol, ketamine, etomidate, Barbiturate (1) (thiopental) Benzodiazepines (28) (midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, potassium Sedatives clorazepate, bromazepam, clobazam, alprazolam, pinazepam, (32 drugs) nordazepam, fludiazepam, ethyl loflazepate, etizolam, clotiazepam, tofisopam, flurazepam, flunitrazepam, estazolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, temazepam, brotizolam, quazepam, loprazolam, zopiclone, zolpidem) Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, morphine, Opioid analgesics hydromorphone, nicomorphine, oxycodone, tramadol, (10 drugs) pethidine Acetaminophen, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (36) (celecoxib, polmacoxib, etoricoxib, nimesulide, aceclofenac, acemetacin, amfenac, cinnoxicam, dexibuprofen, diclofenac, emorfazone, Non-opioid analgesics etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, (44 drugs) ketoprofen, ketorolac, lornoxicam, loxoprofen, mefenamiate, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, pranoprofen, proglumetacin, sulindac, talniflumate, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, zaltoprofen, morniflumate, pelubiprofen, indomethacin), Anticonvulsants (7) (gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lacosamide) Vecuronium, rocuronium bromide, cisatracurium, atracurium, Neuromuscular hexafluronium, pipecuronium bromide, doxacurium chloride, blocking agents fazadinium bromide, mivacurium chloride, (12 drugs) pancuronium, gallamine, succinylcholine -

Benzodiazepines Vs Barbiturates for Alcohol Withdrawal: Analysis of 3 Different Treatment Protocols

American Journal of Emergency Medicine 37 (2019) 733–736 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect American Journal of Emergency Medicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ajem Brief Report Benzodiazepines vs barbiturates for alcohol withdrawal: Analysis of 3 different treatment protocols Amelia C. Nelson a, Joy Kehoe a, Jeffrey Sankoff b, David Mintzer c, Julie Taub c, Kevin A. Kaucher a,⁎ a Department of Pharmacy, Denver Health Medical Center, 777 Bannock ST. MC #0056, Denver, CO 80204, United States of America b Department of Emergency Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, 777 Bannock Street, MC #0108, Denver, CO 80204, United States of America c Department of Medicine, Denver Health Medical Center, 601 Broadway Street, MC 4000, Denver, CO 80203, United States of America article info abstract Article history: Introduction: Alcohol withdrawal treatment varies widely. Benzodiazepines are the standard of care, with rapid Received 19 December 2018 onset and long durations of action. Recent drug shortages involving IV benzodiazepines have required incorpo- Accepted 2 January 2019 ration of alternative agents into treatment protocols. Phenobarbital has similar pharmacokinetics to select ben- zodiazepines frequently used for alcohol withdrawal. The objective of this study is to describe the effectiveness Keywords: and safety of our institutional protocols during three time periods utilizing benzodiazepines and barbiturates Phenobarbital for the acute treatment of alcohol withdrawal in the emergency department. Benzodiazepines Methods: Adult patients presenting to the ED for acute alcohol withdrawal from April 1st, 2016 to January 31st, Diazepam Lorazepam 2018 were reviewed. Patients who received at least one dose of treatment were included. Treatments were Alcohol withdrawal based on availability of medication and given protocol at time of presentation. -

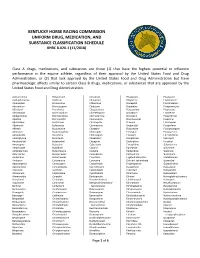

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

The Effects of Antiepileptic Inducers in Neuropsychopharmacology, a Neglected Issue

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Psychiatry Faculty Publications Psychiatry 7-2015 The ffecE ts of Antiepileptic Inducers in Neuropsychopharmacology, a Neglected Issue. Part II: Pharmacological Issues and Further Understanding Jose de Leon University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/psychiatry_facpub Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Repository Citation de Leon, Jose, "The Effects of Antiepileptic Inducers in Neuropsychopharmacology, a Neglected Issue. Part II: Pharmacological Issues and Further Understanding" (2015). Psychiatry Faculty Publications. 36. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/psychiatry_facpub/36 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychiatry at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychiatry Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Effects of Antiepileptic Inducers in Neuropsychopharmacology, a Neglected Issue. Part II: Pharmacological Issues and Further Understanding Notes/Citation Information Published in Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental, v. 8, issue 3, p. 167-188. © 2015 Elsevier B.V. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Digital Object Identifier (DOI) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2014.10.005 This article is available at UKnowledge: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/psychiatry_facpub/36 The Effects of Antiepileptic Inducers in Neuropsychopharmacology, a Neglected Issue. Part II: Pharmacological Issues and Further Understanding Jose de Leon © 2015 Elsevier B.V. -

United States, Lorazepam, with Its Longer Half-Life Compared Appropriate As Initial Treatment for Generalized Tonic-Clonic Et

In the United States, lorazepam, with its longer half-life compared to diazepam, is considered most appropriate as initial treatment for generalized tonic-clonic status epilepticus. (Wheless JW et al. Eds. Treatment of pediatric epilepsy: Expert opinion 2005. J Child Neurol Dec 2005;20(Suppl 1):S46-S49). If the seizure continues despite the maximum dose of benzodiazepine, this is followed with IV fosphenytoin as the most appropriate second drug selection. TOPIRAMATE AND VALPROATE COMPARED IN TREATMENT OF JUVENILE MYOCLONIC EPILEPSY A pilot, randomized, controlled trial comparing topiramate (n=19) and valproate (n=9) in adolescents/adults with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) was conducted in the Childrens Hospitals of Denver, CO, and Cincinnati, OH. Of patients completing a 26 week trial of these agents titrated to optimal effect, 8 of 12 (67%) in the topiramate group and 4 of 7 (57%) in the valproate group were seizure-free during the 12-week maintenance period. Median daily doses were 250 mg topiramate and 750 mg valproate. Adverse events resulted in discontinuance of treatment in 2 (11%) of topiramate-treated and one (11%) valproate- treated patients. Valproate had a higher incidence of systemic toxicity than topiramate, including nausea (33%), weight gain (22%), increased appetite (22%), alopecia (33%) and rash (22%). A double-blind trial of topiramate in JME is recommended. (Levisohn PM, Holland KD. Topiramate or valproate in patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy: A randomized open-label comparison. Epilepsy & Behavior 2007;10:547-552). COMMENT. Topiramate may be an effective alternative treatment to valproate for juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME). An expert opinion panel rated valproate and lamotrigine as most appropriate treatment for JME in males, and lamotrigine followed by topiramate in females. -

Muscle Relaxants for Pain Management in Rheumatoid Arthritis (Review)

Muscle relaxants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis (Review) Richards BL, Whittle SL, Buchbinder R This is a reprint of a Cochrane review, prepared and maintained by The Cochrane Collaboration and published in The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 1 http://www.thecochranelibrary.com Muscle relaxants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis (Review) Copyright © 2012 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 3 BACKGROUND .................................... 6 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 7 METHODS ...................................... 7 RESULTS....................................... 10 Figure1. ..................................... 11 Figure2. ..................................... 13 Figure3. ..................................... 15 Figure4. ..................................... 15 Figure5. ..................................... 16 Figure6. ..................................... 17 Figure7. ..................................... 17 Figure8. ..................................... 18 DISCUSSION ..................................... 20 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 21 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 22 REFERENCES ..................................... 22 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 24 DATAANDANALYSES. 35 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Muscle relaxant versus control, Outcome 1 Pain 24hrs. 37 Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Muscle relaxant -

Clinically Relevant Drug-Drug Interaction Between Aeds and Medications Used in the Treatment of COVID-19 Patients

Updated to March 24, 2020 Clinically relevant Drug-Drug interaction between AEDs and medications used in the treatment of COVID-19 patients The Liverpool Drug Interaction Group (based at the University of Liverpool, UK), in collaboration with the University Hospital of Basel (Switzerland) and Radboud UMC (Netherlands) (http://www.covid19-druginteractions.org/) is constantly updating a list of interactions for many comedication classes. This table is adapted from their valuable work and includes other drugs. In light of pharmacological interaction, single cases management is mandatory. Drugs reported (constantly updated): ATV, atazanavir; DRV/c, darunavir/cobicistat LPV/r, lopinavir/ritonavir; RDV, remdesivir/GS-5734; FAVI, favipiravir; CLQ, chloroquine; HCLQ, hydroxychloroquine; NITA, nitazoxanide; RBV, ribavirin; TCZ, tocilizumab; IFN-β-1a; interferon β-1a; OSV, oseltamivir. IFN-β- ATV *DRV/c1 *LPV/r RDV2 FAVI CLQ HCLQ NITA RBV TCZ3 OSV 1a4 Brivaracetam ↔ ↔ ↓ ↔ ↔ ↑ ↑ ↔ ↑ ↔ ↔ ↔ Carbamazepine ⇓ ↑ ⇓ ↑ ⇓ ↑ ⇓ ↔ ⇓ ⇓ ↔ ↔ ↓ ↔ ↔ Cannabidiol ↔ ↑ ↑ ↔ ↔ ↑ ↑ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Cenobamate ⇓ ⇓ ⇓ ↔ ↔ ⇓ ⇓ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Clonazepam ↑ ↑ ↑ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Clobazam ↑ ↑ ↑ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Diazepam ↑ ↑ ↑ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Eslicarbazepine ⇓♥ ⇓ ⇓♥ ⇓ ↔ ⇓ ⇓ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Ethosuximide ↑ ↑ ↑ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Felbamate ↓ ⇓ ↓ ↔ ↔ ♥ ↓ ♥ ↓ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Gabapentin ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Lacosamide ♥ ↔ ⇑ ♥ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Lamotrigine ↔ ↑ ↓ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Levetiracetam ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Lorazepam ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Oxcarbazepine ⇓ ⇓ ↓ ⇓ ⇓ ↔ ⇓ ⇓ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ ↔ Perampanel ↑ -

Outpatient Treatment for Withdrawal from Alcohol and Benzodiazepines

Considerations for Crisis Centers and Clinicians in Managing the Treatment of Alcohol or Benzodiazepine Withdrawal during the COVID-19 Epidemic: March 19, 2020 Overview: The COVID-19 Epidemic has created countless primary and secondary challenges for those delivering care to our most vulnerable populations. An additional concern has arisen for those with alcohol use disorder, benzodiazepine use disorder, or other conditions that increase the risk of seizures. While we recognize that there is high variability in the capacity for crisis centers and practitioners to receive and treat these individuals, we offer precautionary guidance to those that are prepared and capable. Alcohol use disorder, depending on the severity can be managed at various treatment settings. Those determined to be at high risk for withdrawal complications should receive treatment at higher levels of care, but crisis centers may be faced with a surge of patients seeking relief. Some of these patients can be safely managed at crisis centers. These patients would benefit from receiving medications to ameliorate some withdrawal symptoms and prevent withdrawal complications. Benzodiazepines are frequently utilized in a tapering fashion for medical withdrawal from alcohol or benzodiazepine dependence. It is likely that individuals will have difficulty being admitted to a facility that could safely administer these medications and there will be need for outpatient management of these conditions in the current medical emergency presented by the COVID-19 epidemic. SAMHSA urges providers to consider utilizing benzodiazepines in situations in which they believe that the individual would not benefit from administration of anticonvulsant medications that have been effective in treatment of alcohol withdrawal. -

Antiepileptic Drugs for Epilepsy

Antiepileptic Drugs for Epilepsy EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES After completing this activity, participants should be better able to: 1. Define the difference between a seizure and epilepsy. 2. Identify causes and risk factors associated with epilepsy. 3. Understand the proposed pathophysiology of seizures. 4. Describe the mechanism of action of AEDs used in the management of epilepsy. 5. Assess adverse effects and potential drug-drug interactions associated with the use of AEDs CE EXAM RATIONALE 1. Epilepsy is: A. The most common neurologic disorder worldwide B. A chronic condition in which patients experience recurrent, unprovoked seizures*** C. An isolated event resulting from abnormal electrical disturbances in the brain D. Not classified based on seizure type Correct answer: B Epilepsy is defined as a chronic condition in which patients experience recurrent, unprovoked seizures that range from short-lived intervals of inattention or muscle jerking to severe and elongated convulsions. It is the fourth most common neurologic disorder, affecting approximately 65 million people worldwide. The International Classification of Epileptic Seizures classifies seizures as partial (focal) or generalized. 2. Possible causes of epilepsy and seizures include: A. Stroke B. Head trauma C. Medications such as antidepressants and antipsychotics D. All of the above*** Correct answer: D The cause of epilepsy is idiopathic in origin in approximately half of all patients. However, several medical conditions have an associated risk or causation with epilepsy, including traumatic brain injury (TBI), CNS infections, hypoglycemia, eclampsia, fever, and stroke. In addition, many medications have been associated with precipitating seizures (Table 1). 3. Mechanisms of seizure control include all of the following except: A.