The Artist Reinvented Combining Delicately

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constructivist Book Design: Shaping the Proletarian Conscience

Constructivist Book Design: Shaping the Proletarian Conscience We . are satisfied if in our book the lyric and epic Futurist books were unconventionally small, and whether Margit Rowell evolution of our times is given shape. —El Lissitzky1 or not they were made by hand, they deliberately empha- sized a handmade quality. The pages are unevenly cut One of the revelations of this exhibition and its catalogue and assembled. The typed, rubber- or potato-stamped is that the art of the avant-garde book in Russia, in the printing or else the hectographic, or carbon-copied, early decades of this century, was unlike that found any- manuscript letters and ciphers are crude and topsy-turvy where else in the world. Another observation, no less sur- on the page. The figurative illustrations, usually litho- prising, is that the book as it was conceived and pro- graphed in black and white, sometimes hand-colored, duced in the period 1910–19 (in essentially what is show the folk primitivism (in both image and technique) known as the Futurist period) is radically different from of the early lubok, or popular woodblock print, as well as its conception and production in the 1920s, during the other archaic sources,3 and are integrated into and inte- decade of Soviet Constructivism. These books represent gral to, as opposed to separate from, the pages of poetic two political and cultural moments as distinct from one verse. The cheap paper (sometimes wallpaper), collaged another as any in the history of modern Europe. The covers, and stapled spines reinforce the sense of a hand- turning point is of course the years immediately follow- crafted book. -

Soviet Books 2015

www.bookvica.co.com 2015 EARLY SOVIET BOOKS 1917-1940 4. [STENBERG BROTHERS DESIGN] 4. [STENBERG BROTHERS DESIGN] O'NEILL, E.G. Lyubov' pod vyazami. Pyesa v tryokh deistviyakh / Perevod P. O'NEILL, E.G. Lyubov' pod vyazami. Pyesa v tryokh deistviyakh / Perevod P. Zenkevicha i N. Krymovoi [Desire under the Elms: Three act play / Translat- Zenkevicha i N. Krymovoi [Desire under the Elms: Three act play / Translat- ed by P.Zenkevich and N. Krymova]. Moscow; Leningrad: MODP i K, 1927. 48 ed by P.Zenkevich and N. Krymova]. Moscow; Leningrad: MODP i K, 1927. 48 pp.: ill. 24x16 cm. In original illustrated wrappers. Covers rubbed, some pp.: ill. 24x16 cm. In original illustrated wrappers. Covers rubbed, some foxing, light crease and previos owner's pencil signature on the first page. foxing, light crease and previos owner's pencil signature on the first page. Otherwise very good. Otherwise very good. First edition of the play. The poster to the play Desire under the Elms made by Stenberg First edition of the play. The poster to the play Desire under the Elms made by Stenberg brothers was used for the front cover of this edition. The play was first staged in Russian brothers was used for the front cover of this edition. The play was first staged in Russian in the Kamerny Theatre by A. Tairov in 1926. Stenberg brothers were invited as artists to in the Kamerny Theatre by A. Tairov in 1926. Stenberg brothers were invited as artists to this production. The text is accompanied by a few photographs taken during the play. -

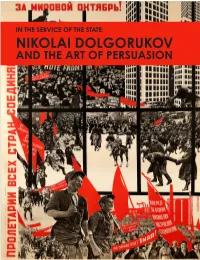

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Art and Technology Between the Usa and the Ussr, 1926 to 1933

THE AMERIKA MACHINE: ART AND TECHNOLOGY BETWEEN THE USA AND THE USSR, 1926 TO 1933. BARNABY EMMETT HARAN PHD THESIS 2008 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ANDREW HEMINGWAY UMI Number: U591491 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591491 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Bamaby Emmett Haran, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis concerns the meeting of art and technology in the cultural arena of the American avant-garde during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It assesses the impact of Russian technological Modernism, especially Constructivism, in the United States, chiefly in New York where it was disseminated, mimicked, and redefined. It is based on the paradox that Americans travelling to Europe and Russia on cultural pilgrimages to escape America were greeted with ‘Amerikanismus’ and ‘Amerikanizm’, where America represented the vanguard of technological modernity. -

Images of the Worker in John Heartfield's Pro-Soviet Photomontages a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School A

Images of the Worker in John Heartfield’s Pro-Soviet Photomontages A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by DANA SZCZECINA Dr. James van Dyke, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2020 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled IMAGES OF THE WORKER IN JOHN HEARTFIELD’S PRO=SOVIET PHOTOMONTAGES Presented by Dana Szczecina, a candidate for the degree of master of the arts , and hereby certify that in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor James van Dyke Professor Seth Howes Professor Anne Stanton ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply grateful for the guidance and support of my thesis adviser Dr. van Dyke, without whom I could not have completed this project. I am also indebted to Dr, Seth Howes and Dr. Anne Stanton, the other two members of my thesis committee who provided me with much needed and valuable feedback. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………………………………………ii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS……………………………………………………………………………….iv ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………………..vii Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter One……………………………………………………………………………………………...11 Chapter Two……………………………………………………………………………………………25 Chapter Three……………………………………………………………………………………………45 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………...68 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………………………….71 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Film und Foto, Installation shot, Room 3, 1929. Photograph by Arthur Ohler. (Akademie der Künste, Berlin, Archiv Bildende Kunst.)…………………………….1 2. John Heartfield, Five Fingers Has the Hand, 1928 (Art Institute Chicago)…………………………………………………………………..1 3. John Heartfield, Little German Christmas Tree, 1934 (Akademie der Künste)…………………………………………………………………3 4. Gustav Klutsis, All Men and Women Workers: To the Election of the Soviets, 1930 (Art Institute Chicago)……………………………………………………………6 5. -

Constructivism (Art) 1 Constructivism (Art)

Constructivism (art) 1 Constructivism (art) Constructivism was an artistic and architectural philosophy that originated in Russia beginning 1919, which was a rejection of the idea of autonomous art in favour of art as a practice for social purposes. Constructivism as an active philosophy lasted until about 1934, greatly effecting the art of the Weimar Republic and elsewhere, before being replaced by Socialist Realism. Some of its motifs have been reused sporadically since. Beginnings The term Construction Art was first used as a derisive term by Kazimir Malevich to describe the work of Alexander Rodchenko during 1917. Constructivism first appears as a positive term in Naum Gabo's Realistic Manifesto of 1920. Alexei Gan used the word as the title of his book Constructivism, which was printed during 1922.[1] Constructivism was a post-World War I development of Russian Futurism, and particularly of the 'corner-counter reliefs' of Vladimir Tatlin, which had been exhibited during 1915. The term itself would be invented by the sculptors Antoine Pevsner and Naum Photograph of the first Constructivist Exhibition, 1921 Gabo, who developed an industrial, angular style of work, while its geometric abstraction owed something to the Suprematism of Kasimir Malevich. The teaching basis for the new ohilosophy was established by The Commissariat of Enlightenment (or Narkompros) the Bolshevik government's cultural and educational ministry directed by Anatoliy Vasilievich Lunacharsky who suppressed the old Petrograd Academy of Fine Arts and the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture during 1918. IZO, the Commissariat's artistic bureau, was managed during the Russian Civil War mainly by Futurists, who published the journal Art of the Commune. -

Stalin's Russia: Visions of Happiness, Omens of Terror Mark Konecny Institute of Modern Russian Culture, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Art Faculty Creative Works – Exhibitions Art Faculty Creative Works 2014 Stalin's Russia: Visions of Happiness, Omens of Terror Mark Konecny Institute of Modern Russian Culture, [email protected] Wendy Salmond Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_exhibitions Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, Political History Commons, Slavic Languages and Societies Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Konecny, Mark and Salmond, Wendy, "Stalin's Russia: Visions of Happiness, Omens of Terror" (2014). Art Faculty Creative Works – Exhibitions. Book 18. http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/art_exhibitions/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Art Faculty Creative Works at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art Faculty Creative Works – Exhibitions by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY PRESS PRESS CHAPMAN PRESSAn exhibition exploringUNIVERSITY the power PRESS of visual propaganda. From the Ferris Russian Collection, PRESSthe Institute of Modern Russian CultureCHAPMAN at USC, UNIVERSITY and the Wende Museum, Culver City. PRESS CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY PRESS CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY PRESS CHAPMAN UNIVERSITY PRESS MMXIV 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS e wish to express our deep gratitude to the lenders and institutions whose Wgenerosity has made this exhibition possible: to Mrs. Jeri Ferris and her late husband Tom, who assembled an unparalleled collection of Staliniana; to the Institute of Modern Russian Culture at USC and its director, John E. -

Checklist of the Judith Rothschild Foundation Gift

Checklist of The Judith This checklist is a comprehensive ascertained through research. When a For books and journals, dimensions Inscriptions that are of particular his- record of The Judith Rothschild place of publication or the publisher given are for the largest page and, in torical or literary interest on individual Rothschild Foundation Gift Foundation gift to The Museum of was neither printed in the book nor cases where the page sizes vary by books are noted. Modern Art in 2001. The cataloguing identified through research, the des- more than 1/4,” they are designated Coordinated by Harper Montgomery system reflects museum practice in ignation “n.s” (not stated) is used. irregular (“irreg.”). For the Related The Credit line, Gift of The Judith under the direction of Deborah Wye. general and the priorities of The Similarly, an edition size is some- Material, single-sheet dimensions in Rothschild Foundation, pertains to all Museum of Modern Art’s Department times given as “unknown” if the print which the height or width varies from items on this checklist. To save space Researched and compiled by of Prints and Illustrated Books in par- run could not be verified. City names one end to the other by more than and avoid redundancy, this line does Jared Ash, Sienna Brown, Starr ticular. Unlike most bibliographies are given as they appear printed in 1/4” are similarly designated irregular. not appear in the individual entries. Figura, Raimond Livasgani, Harper and library catalogues, it focuses on each book; in different books the An additional credit may appear in Montgomery, Jennifer Roberts, artists rather than authors, and pays same city may be listed, for example, Medium descriptions (focusing on parentheses near the end of certain Carol Smith, Sarah Suzuki, and special attention to mediums that as Petersburg, St. -

A “Russianesque Camera Artist”: Margaret Bourke- White's American

ISSN: 2471-6839 Cite this article: Josie Johnson, “A ‘Russianesque Camera Artist’: Margaret Bourke-White’s American- Soviet Photography,” Panorama: Journal of the Association of Historians of American Art 6, no. 2 (Fall 2020), https://doi.org/10.24926/24716839.10572. A “Russianesque Camera Artist”: Margaret Bourke- White’s American-Soviet Photography Josie Johnson, Capital Group Foundation Curatorial Fellow for Photography, Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts, Stanford University In May 1930, an unnamed journalist for the Dayton Daily News penned a brief article under the heading “Beauty in Industry Is Shown by Photographer in Unique Plat Studies.”1 The subject of the report was Margaret Bourke-White (1904–1971), a twenty-five-year-old photographer raised in New Jersey and based in Cleveland at the time. Her skill in transforming industrial subjects into art and her recent hire by the new business magazine Fortune attracted broad notice in the press. The Dayton Daily supplied a typical profile, emphasizing Bourke-White’s youth and her fearless determination to work around heavy machinery. Yet one phrase in the article stands out—her description as a “Russianesque camera artist.” Today, Bourke-White is remembered as a globetrotting photojournalist for Life magazine. But before joining Life in 1936, she had brokered a unique arrangement with Fortune magazine in 1929, spending half her time as its star photographer of business and industry features, and half her time on personal projects (mostly consisting of advertising commissions) at the Bourke-White Studio.2 It was in the latter capacity as an independent photographer that she first traveled to Russia in 1930, then returned twice, in 1931 and 1932.3 Over the course of these three trips, she created an extensive body of photographs that would be featured in her first book, Eyes on Russia (1931), a six-part series in the New York Times (1932), a deluxe photo portfolio (1934), and a set of photomurals for the Soviet consulate in New York (1934). -

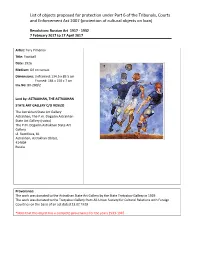

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Yury Pimenov Title: Football Date: 1926 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 134.5 x 89.5 cm Framed: 184 x 150 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/2 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery ul. Sverdlova, 81 Astrakhan, Astrakhan Oblast, 414004 Russia Provenance: The work was donated to the Astrakhan State Art Gallery by the State Tretyakov Gallery in 1929. The work was donated to the Tretyakov Gallery from All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries on the basis of an act dated 23.02.1929 *Note that this object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Ekaterina Zernova Title: Tomato Paste Factory Date: 1929 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 141 x 110 cm Framed: 150 x 120 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/1 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. -

7.10 Nov 2019 Grand Palais

PRESS KIT COURTESY OF THE ARTIST, YANCEY RICHARDSON, NEW YORK, AND STEVENSON CAPE TOWN/JOHANNESBURG CAPE AND STEVENSON NEW YORK, RICHARDSON, YANCEY OF THE ARTIST, COURTESY © ZANELE MUHOLI. © ZANELE 7.10 NOV 2019 GRAND PALAIS Official Partners With the patronage of the Ministry of Culture Under the High Patronage of Mr Emmanuel MACRON President of the French Republic [email protected] - London: Katie Campbell +44 (0) 7392 871272 - Paris: Pierre-Édouard MOUTIN +33 (0)6 26 25 51 57 Marina DAVID +33 (0)6 86 72 24 21 Andréa AZÉMA +33 (0)7 76 80 75 03 Reed Expositions France 52-54 quai de Dion-Bouton 92806 Puteaux cedex [email protected] / www.parisphoto.com - Tel. +33 (0)1 47 56 64 69 www.parisphoto.com Press information of images available to the press are regularly updated at press.parisphoto.com Press kit – Paris Photo 2019 – 31.10.2019 INTRODUCTION - FAIR DIRECTORS FLORENCE BOURGEOIS, DIRECTOR CHRISTOPH WIESNER, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR - OFFICIAL FAIR IMAGE EXHIBITORS - GALERIES (SECTORS PRINCIPAL/PRISMES/CURIOSA/FILM) - PUBLISHERS/ART BOOK DEALERS (BOOK SECTOR) - KEY FIGURES EXHIBITOR PROJECTS - PRINCIPAL SECTOR - SOLO & DUO SHOWS - GROUP SHOWS - PRISMES SECTOR - CURIOSA SECTOR - FILM SECTEUR - BOOK SECTOR : BOOK SIGNING PROGRAM PUBLIC PROGRAMMING – EXHIBITIONS / AWARDS FONDATION A STICHTING – BRUSSELS – PRIVATE COLLECTION EXHIBITION PARIS PHOTO – APERTURE FOUNDATION PHOTOBOOKS AWARDS CARTE BLANCHE STUDENTS 2019 – A PLATFORM FOR EMERGING PHOTOGRAPHY IN EUROPE ROBERT FRANK TRIBUTE JPMORGAN CHASE ART COLLECTION - COLLECTIVE IDENTITY -

October 2017 • V

October 2017 • v. 57, n. 5 NewsNet News of the Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies Article Written: 1917 for 2017 Kristin Romberg, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign When the editors of NewsNet asked me months ago to digging in archives and carefully crafting a narrative to contribute something on the current state of scholarship about how the revolution mattered (in my case, to aesthetic about art produced in the context of the Russian Revolution, modernism), it has been a giddy delight to see the issues I planned to write about the repositioning of the field that motivate my work actually matter both to a broader in the past ten years; how the receding relevance of the audience and in relation to world events. At the same time, Cold War paradigms that once made our work “topical” that brighter spotlight and larger pool of participants have in Title VIII terms has been as much an opportunity as a been accompanied by the discomfort of misrecognition challenge; how a decreasing appetite for Manichean hero/ and the awkward illumination of some of the quirks of villain structures has allowed new figures, histories, and academe. The disciplinary boundaries and psychological questions to become visible and opened up a new set of compartmentalizations that gird scholarly endeavors discursive frames. As I sat down to write, however, the (in my opinion, necessarily) appear less like an infinite ghosts all returned in the form of the question that haunts horizon and more like the “silos” that administrators keep this centennial year: how do we think about the Russian telling us that they are.