Changing Hydrosocial Cycles in Periurban India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

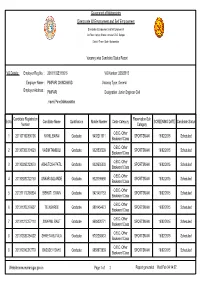

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

Earthen Swapnapurti by Earthen Group

Earthen Swapnapurti By Earthen Group Uruli Kanchan Pune Near Harjeevan Hospital Plots from 6 Lakhs Launch Date Not Available Expected Possession Not Available Floor Plans Not Available Overview of Earthen Swapnapurti Pune is expanding rapidly with more sophisticated life and very less opportunity for a peaceful life. Earthen Group brings the prospects of a much tangible life style that suits for people who belong to the nature. Earthen Group launches “Swapnapurti”a project of developed bungalow plots in this blessed village of Urli Kanchan. The project is of total 6 acres, with ample amenities. We are quoting a pre-launch offer of Rs.499/- per sqft Urli Kanchan is a village 33 kms East of Pune. The village has been famous for its Naturopathy Centre (Nisarg Upchar Ashram) which was started by Mahatma Gandhi in the 1960s. It is surrounded by beautiful mountain range of Sinhagad – Bhuleshwar towards the South, Mula-Mutha river flowing towards the north and with the pilgrim center of Jejuri on the other side of the mountain range. PMRDA (Pune Metropolitan Region Development Authority) has proposed The latest development in this region as the (MADC) Maharshtra Airport Development Company proposes, is the Pune International Airport near Waghapur and Rajewadi village stretching to almost 1200-1500 hectares that will set the location in a drastic change of business, hotels, cargo handling, tourism services and many other commercial activities, simultaneously fetching a higher ROI on the project. The State government paved the way for PMRDA’s formation in March 2016. Areas around Pune such as Maval and Mulshi are starting to see similar rapid growth with several housing projects and tourism destinations coming up. -

Study of Challenges Faced by Farmers Related to Irrigation Water for Increasing Crop Production

Asian Journal of Advances in Agricultural Research 12(2): 1-6, 2020; Article no.AJAAR.54381 ISSN: 2456-8864 Study of Challenges Faced by Farmers Related to Irrigation Water for Increasing Crop Production Vineetha Chinthalu1, Narayan G. Hegde2* and Ashwini Supekar3 1Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, India. 2BAIF Development Research Foundation, Pune, India. 3Department of Geology, Savitribai Phule Pune University, Pune, India. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Author VC designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, managed the analyses of the study and managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJAAR/2020/v12i230074 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Daniele De Wrachien, Retired Professor, Department of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, The State University of Milan, Italy. Reviewers: (1) Éva Pék, Kaposvár University, Hungary. (2) Hussin Jose Hejase, Al Maaref University, Lebanon. (3) Minithra Sivakumar, Tamil Nadu Agricultural University, India. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/54381 Received 24 November 2019 Accepted 28 January 2020 Original Research Article Published 05 February 2020 ABSTRACT The objective of this study was to evaluate the groundwater scenario in Haveli block of Pune district in Maharashtra, India. An interdisciplinary approach and techniques in both natural and social sciences was used, to unravel how local hydrogeological conditions and institutional arrangements interact and contribute to water problems. The study also attempted to understand the sources of water available for irrigation, methods of irrigation followed by farmers and to suggest how to improve the surface water use for increasing crop yield and area coverage. -

College : P.M.D. College Uruli Kanchan

A Brief Bio-Data Name : Dr.Shaikh. Kamarunnissa Abdul Hamid Birth Date : 22 October 1979. College : P.M.D. College Uruli Kanchan. Subject : Commerce Designation : Assistant Professor of Commerce Correspondence Address: Iqbal Sound Service, FarateGalli, Tal- Daund, Dist- Pune. Pin Code: 413801.phon - 9766737394 Mobile : 9766737394 E-mail : [email protected] 1) Academic Achievements: Examinations Name of the Board / Year of Percentage Division Subject University Passing of marks / Class/ obtained Grade S.S.C. Maharashtra State Board March 1995 59% B+ Maths, Science, of Secondary and Higher Marathi, Hindi, Secondary Education, English, Social Mumbai Science. H.S.C. Maharashtra State Board March 1997 58.83 % B+ Marathi, of Secondary and Higher English, Secondary Education, Account, Mumbai S/p,O/C, Ecco B.com. Higher Special Banking, University of Pune. March 2000 56.60 % Second Class M.Com. Higher Special Banking, University of Pune. May 2002 55.55 % Second Class M.Phil A study of silk Y. C. M. O. U. Nashik 2009 66.43 % 1st class product in daunt taluka Ph.D Public sector University of Pune support for submitted the Ph.D. 2018 -------- -------- agriculture Thisese development - Higher B.ED University of Pune. 2012 -------- Second Science, Maths. Class Department of Co- GDC&A May 2001 1st class -------- operation Others Information Technology 2004 73% -------- -------- examination, if any 1. MS-CIT 2.Tally Information Technology 2000 61% -------- -------- 3.Office Information Technology 1998 B+ -------- -------- Automation 4.Typing in 1998 67% -------- -------- English 30 W.P.M. 2) Papers presented in Conference / seminars / workshops: Sr, No Title of the paper Title of Organized By Place Whether presented Conference / international / Seminar National/State/ Regional/College or University level Impact of Impact of University globalisation on globalisation on S.M. -

On a Collection of Centipedes (Myriapoda : Chilopoda) from Pune, Maharashtra

1tIIe. ZDflI. Surv. India, 93 (1-2) : 165-174, 1993 ON A COLLECTION OF CENTIPEDES (MYRIAPODA : CHILOPODA) FROM PUNE, MAHARASHTRA. B. E. YADAV Zoological Survey of India Western Regional Station Pune-411 005. INTRODUCTION The Centipedes are an important group of organisms. They are poisonous, cryptic, solitary, carnivorous and nocturnal. Their distribution and taxonomy have been studied by Attems (1930). The centipedes from Deccan area are reported by Jangi and Dass (1984). However, there is no upto-date account of centipedes occuring in and around Pune, Maharashtra. On the basis of huge collection present in the Western Regional Station, Pune, an attempt has been made to record centipedes from Pune district. The present paper deals with six genera comorising eighteen species of centipedes belongIng to the family Scolopendridae, mostly collected from Haveli taluka (Fig. 1). Occasionally bling centipedes (Cryptopidae) as well as long centipedes possessing more than 21 trunk segments, were also observed. DESCRIPTION ON LOCALITIES Pune city is situated 18 0 35' North latitude and 73° 53' East longitude at 558.6 m above MSL, with normal rainfall 675 mm per year in Maharashtra State. Centipedes were collected in the vicinity of Pune from Haveli, Khed, Maval, Ambegaon, Sirur and Purandar talukas. Haveli taluka ; Eastern portion of this taluka is characterised by brown soil and mixed deciduous forest. 1. Akurdi: Akurdi is a small village situated 18 kms. NW of pune and at 575 m above MSL. This area occupies many stones and boulders. 2. Bhosri: Bhosri is a suburban area, 19 km. N of Pune on ~une-Nasik road. -

Articulating Masculinity and Space in Urban India

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE July 2016 Making Men in the City: Articulating Masculinity and Space in Urban India Madhura Lohokare Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Lohokare, Madhura, "Making Men in the City: Articulating Masculinity and Space in Urban India" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 520. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/520 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract In my dissertation, I illustrate the way in which processes in contemporary urban India structure the making/ unmaking of gendered identities for young men in a working class, scheduled caste neighborhood in the western Indian city of Pune. Present day Pune, an aspiring metropolis, presents a complex socio-spatial intersection of neoliberal processes and peculiar historical trajectories of caste exclusion; this dissertation seeks to highlight how socio-spatial dynamics of the city produce and sustain gendered identities and inequalities in Pune, a city hitherto neglected in academic research. Also, my focus on young men’s gendered identities speaks to a growing recognition that men need to be studied in gendered terms, as ‘men,’ in order to understand fully the dimensions of gendered inequalities and violence prevalent in South Asian cities today. I follow the lives of young men between 16 and 30 in a neighborhood in the eastern part of Pune, who belong to a scheduled caste called Matang. -

Women Self Help Groups and Sustainability Indices: a Study of Successful Self Help Groups in Uruli Kanchan Village, Pune District

International Journal of Management (IJM) Volume 8, Issue 1, January – February 2017, pp.127–136, Article ID: IJM_08_01_014 Available online at http://iaeme.com/Home/issue/IJM?Volume=8&Issue=1 Journal Impact Factor (2016): 8.1920 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com ISSN Print: 0976-6502 and ISSN Online: 0976-6510 © IAEME Publication WOMEN SELF HELP GROUPS AND SUSTAINABILITY INDICES: A STUDY OF SUCCESSFUL SELF HELP GROUPS IN URULI KANCHAN VILLAGE, PUNE DISTRICT Dr. Sunil Ujagare Dean, M.B.A. Department, NBN Sinhgad School of Management Studies, Sawitribai Phule, Pune University, India Ashwini Bhagwat Research Scholar, Sinhgad Institute of Management Vadgaon (BK) Pune, Sawitribai Phule, Pune University, India ABSTRACT In India half of the population comprises of women but businesses owned and operated by them constitute less than 5%. This is the reflection of developing India on social, cultural as well as economic front. Women Self Help Groups in India are formed with a view to mobilize savings of poor and marginal sectors of society. This will help to eradicate poverty and strengthening of weaker sections of society. With this view Self Help Groups in Maharashtra are formed in the form of village organizations under the guidelines provided in’ Dashasutras’. Formation of self help groups is much easier process than to make them sustainable. This paper discusses about various indices which influence sustainability of self help groups. Those indices are leadership index, index of meeting, record keeping index, conflict index, goal clarity index. Each index factor is considered as index of sustainability. Using confidence interval method analysis mean of indices is calculated and conclusions are drawn. -

Vishwashanti Sangeet Kala Academy Rajbaug, Pune, India

WORLD PEACE CENTRE (ALANDI), MAEER MIT'S VISHWASHANTI SANGEET KALA ACADEMY RAJBAUG, PUNE, INDIA ic us M h ug ro Th d Go of on Realizati w w w. m i t v s k a . c o m The Golden Voice One Man, Many Visions The living legend of singing, Bharat Dr. Vishwanath D. Karad is the Ratna Smt. Lata Mangeshkar is the Founder of MAEER’s MIT Group of Chairperson of VSKA. She is the face Institutions, Pune. He is a great of Indian music in its rich and varied visionary educationist, who forms and has been serving the revolutionized the professional world of music for over 70 incredible education scenario in the country in years! It is indeed a rare honour for the 80s by pursuing the cause of VSKA to be associated with the unaided institutes of education. He Golden Voice of India – Smt. Lata is also the pioneer of ‘Value-based Smt. Lata Mangeshkar Mangeshkar! Dr. Vishwanath D. Karad Universal Education System’ for the Chairperson Founder, Executive President holistic development of the students. Governing Council (proposed) Pandit Jasraj is one of the most revered and respected classical vocal artistes of India belonging to the Mewati gharana. Even at 83, Pandit Jasraj has the ability to perform difficult compositions with great ease. He is the recipient of many awards and honours, one of them being the Padma Vibhushan from the Government of India. Pandit Jasraj He is regarded as one of the topmost players of the Hindustani Bansuri (flute) in the world. He is instrumental in bringing great popularity to flute as a solo instrument in classical recitals not just in India, but also at an international level. -

District Census Handbook, Pune

CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PUNE Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS DIRECTORATE BOMBAY PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE MANAGER, GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS, BOMBAY AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONERY AND PUBLICATIONS, MAHARASHTRA STATE, BOMBAy-400 004. 1986 [Price Rs. 30.00] lLJ S c o "" « Z ;! ~a,'~,,_ ~ 0:: :::> ~ g ~ f -~, ~ Q. ~ 0 ~ ~ g :::r: ~ :z: ~ J- ~ § .! 0:: U <S ~ « ~ ::r: 0::: ~ ~ ~ « J- .j ~ 0 (J) ~ ~ ~ LO '5, ~ ~ :'! 'j' ~ 0 c- i '0 .g 02 ~ f:z: li ~~~ti<!::':ZI- It p. (', P. I'- \) <t po. a:: ~ ..(. <t I>- ,. .-~ .;>~<:> <t '- /'\ i ' " U'l C,; \. \ "- i I,~ lC ~1({:;OJ.j , ~. ' .~ ..... .'. a.~ u I/) a:: i' 0 " Ul (' <,' 0 ~/1·...... ·"r·j ,,r-./ C> .tV /& 1'-" , .IS 10 c, It 0- '\. ". ""• ~ :; ,F \. ') V ij c 0 ~ <Il~ MOTIF Shaniwar Wada, once upon a time was the palace of Peshwas (chief executives of the Maratha Kingdom founded by Chhatrapati Shivaji). Peshwas went on conquering places as far as Panipat and Atak and extending the boundaries of the kingdom beyond Chambal river in North India. This finest palace of the time (1730-1818) but now in dilapidated condition is in the heart of the Pune city. This palace as it finally stood was a seven-storeyed building with four large and several small courts some of which were named as Ganapati Rang Mahal, Nach Diwankhana, Arse Maltal, Hastidanti Mahal. Today, the remains (enclosure, plinths and the surrounding wall) are mute witnesses of the past Maratha glory. CENSUS OF INDIA 1981 SERIES 12-MAHARASHTRA DISTRICT PUNE ERRATA SLIP Page Column No Item No. -

Speed Post All List.Xlsx

14th convocation Degree Certificate Speed Post List SL Speed Post Number Pincode Name ADD1 ADD2 ADD3 Degree Code 1 EM569775640IN 413005 Akim Kalpana Chandrakant H.No.46/4 Vinoba Bhave ZopadpDatta nagar Solapur 143608 2 EM569775653IN 413309 Atar Sumaiyya Akbar Gherdi, Sangola Solapur 143609 3 EM569775667IN 413304 Bengale Malhari Arun Gadegaon pandharpur Solapur 143612 4 EM569775675IN 413109 Bhise Bhanudas Waman Phondshiras,Kadalkar wasti Malshiras Solapur 143614 5 EM569775684IN 413005 Chavan Amruta Anil 14/54 Kavita Nagar police Colny Solapur 143619 6 EM569775698IN 413304 Chavan Revansiddha Kashinath Suste solapur Solapur 143620 7 EM569775707IN 413002 Gaikwad Reshma Shrikant 181 Budhwar Peth Milind Nagar Solapur 143625 8 EM569775715IN 413001 Godase Sonali Ganesh 159 Juni Laxmi Chawl Dongaon solapur Solapur 143629 9 EM569775724IN 413225 Gogav Mahantesh Rautappa Salgar aaklkot Solapur 143630 10 EM569775738IN 413216 Gore Shruti Rajshekhar Budhavar Peth Akkalko aaklkot Solapur 143631 11 EM569775741IN 413309 Gujale Jyoti Namadev Hangirage Sangola Solapur 143632 12 EM569775755IN 413008 Gujare Sukeshni Hariba Plot No 168 Ramnaryan Chandakvijapur road Solapur 143633 13 EM569775769IN 413403 Hange Pallavi Mahadev Mirzanpur Barshi Solapur 143634 14 EM569775786IN 413001 Jadhav Swati Santaram Patwardhan Chal Wagi Road Solsolapur Solapur 143640 15 EM569775790IN 413307 Jagtap Pratik Gopinath Methawade Sangola Solapur 143641 16 EM569775809IN 413216 Jainjangade Nitin Vasant Kini aaklkot Solapur 143642 17 EM569775812IN 413003 Jamadar Sana Shamshoddin 51/1 -

Village Map Taluka: Haveli District: Pune

Village Map Taluka: Haveli District: Pune Khed !( Shirur Mawal Dehu (CT) MalinagarVitthal Nagar Dehu Road (CB) µ 4.5 2.25 0 4.5 9 13.5 Borhadewadi km Tulapur Fulgaon Pimpri Chinchwad (M Corp.) Wadhu Kh. Nirgudi Tathavade (CT) Perane Location Index Bhawadi Loni-kand Burkegaon Dongargaon Sangavi Sandas District Index Nandurbar Pimpale Saudagar Bakori Pimpri Sandas Bhandara Pimpale Gurav Nhavi Sandas Dhule Amravati Nagpur Gondiya Wagholi (CT) Jalgaon Shiraswadi Akola Wardha Kesnand Buldana Nashik Washim Chandrapur Gawdewadi (N.V.) Shindewadi Yavatmal Awhalwadi Murkutenagar (N.V.) Palghar Aurangabad Wade Bolhai Jalna Gadchiroli Taleranwadi Ashtapur Hingoli Thane Ahmednagar Parbhani Mumbai Suburban Nanded Bid Manjari Kh. Sashte Hingangaon Mumbai Biwari Pune Sunarwadi Pashan Raigarh Bidar Pune City HAVELI Latur Mulshi !( Osmanabad !( !. !( Bhawarapur Khamgaon Tek Kolwadi Naigaon Satara Solapur Theur Peth Tilekarwadi Ratnagiri Daund Sangli Koregaon Mul Peth Maharashtra State Kolhapur Kadamwak Wasti Uruli Kanchan Sindhudurg Shewalwadi Kunjirwadi Sortapwadi Dharwad Fursungi Khadewadi Taluka Index Loni-kalbhor MokarwadiAhire Shindwane Uruli-dewachi Tarade Junnar Wanjalewadi Alandi Mhatobachi Bhagatwadi Bahuli Autadwadi Handewadi Ambegaon Agalambe Walati Kudaje Wadki Holkarwadi Ramoshiwadi Katavadi Gujar Nimbalkarwadi Khed JambhulwadiMangadewadi Wadachiwadi Khadakwadi Mawal Gorhe Bk. Shirur Mandvi Bk. Nandoshi Sangarun Mandvi Kh. Gorhe Kh. Haveli Kolewadi Bhilarewadi Donaje Khanapur Sanas Nagar Mulshi Pune City Jambhali Malkhed Haveli Manekhadi Daund Thoptewadi Gogalwadi Legend Ghera Sinhagad Tanaji Nagar Velhe Purandhar Wardade Sambarewadi Nigade Mose !( Taluka Head Quarter Bhor Baramati Gaud Dara Khamgaon Mawal Indapur Awasare NagarArvi Ambee Mordhari Railway Kondhanpur Ramnagar Mordari !( Mogarwadi Shiwapur Express Highway Kalyan District: Pune Rahatwade Khed National Highway Purandhar State Highway Village maps from Land Record Department, GoM. -

Jr Engg Civil.Pdf

Government of Maharashtra Directorate Of Employment and Self Employment Directorate of Employment and Self Employment 3rd Floor Konkan Bhavan Annexe C.B.D. Belapur District:-Thane State:- Maharashtra Vacancy wise Candidate Status Report VO Details : Employer Reg.No. : 20101102E110916 VO Number :20025815 Employer Name : PIMPARI CHINCHWAD Vacancy Type :General Employer Address : PIMPARI Designation :Junior Engineer Civil ,Haveli,Pune,Maharashtra Candidate Registration Reservation Sub Sr.No. Candidate Name Qualification Mobile Number Caste Category SCREENING DATE Candidate Status Number Category O.B.C.-Other 1 20110719C900106 NIKHIL BARAI Graduate 9403211011 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015 Scheduled Backward Class O.B.C.-Other 2 20130730C101020 VASIM TAMBOLI Graduate 9028535339 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015 Scheduled Backward Class O.B.C.-Other 3 20130929C123079 ASHUTOSH PATIL Graduate 9028535330 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015 Scheduled Backward Class O.B.C.-Other 4 20130928C122150 ONKAR GOLANDE Graduate 9028799590 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015 Scheduled Backward Class O.B.C.-Other 5 20131111C168894 BIBHUTI SWAIN Graduate 8421407753 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015 Scheduled Backward Class O.B.C.-Other 6 20131120C176697 TEJASHREE Graduate 9881454673 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015 Scheduled Backward Class O.B.C.-Other 7 20131121C177118 SWAPNIL RAUT Graduate 9689220771 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015 Scheduled Backward Class O.B.C.-Other 8 20131208C194602 SHWETA BUTALA Graduate 9762268433 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015 Scheduled Backward Class O.B.C.-Other 9 20131224C212779 BASUDEV SAHU Graduate 9658073839 SPORTSMAN 16/02/2015