Ethel Smyth: Composer, Feminist, Suffragette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRANSNATIONAL SMYTH: SUFFRAGE, COSMOPOLITANISM, NETWORKS Erica Fedor a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty at the University Of

TRANSNATIONAL SMYTH: SUFFRAGE, COSMOPOLITANISM, NETWORKS Erica Fedor A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Annegret Fauser David Garcia Tim Carter © 2018 Erica Fedor ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Erica Fedor: Transnational Smyth: Suffrage, Cosmopolitanism, Networks (Under the direction of Annegret Fauser) This thesis examines the transnational entanglements of Dame Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), which are exemplified through her travel and movement, her transnational networks, and her music’s global circulation. Smyth studied music in Leipzig, Germany, as a young woman; composed an opera (The Boatswain’s Mate) while living in Egypt; and even worked as a radiologist in France during the First World War. In order to achieve performances of her work, she drew upon a carefully-cultivated transnational network of influential women—her powerful “matrons.” While I acknowledge the sexism and misogyny Smyth encountered and battled throughout her life, I also wish to broaden the scholarly conversation surrounding Smyth to touch on the ways nationalism, mobility, and cosmopolitanism contribute to, and impact, a composer’s reputations and reception. Smyth herself acknowledges the particular double-bind she faced—that of being a woman and a composer with German musical training trying to break into the English music scene. Using Ethel Smyth as a case study, this thesis draws upon the composer’s writings, reviews of Smyth’s musical works, popular-press articles, and academic sources to examine broader themes regarding the ways nationality, transnationality, and locality intersect with issues of gender and institutionalized sexism. -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

HANDLEY-THESIS-2021.Pdf (325.2Kb)

MUSICAL WOMEN: A SUBJECT WORTHY OF STUDY By Jenifer Hesselbrock-Handley A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Major Subject: Music West Texas A&M University Canyon, Texas May 2021 Abstract High school and college students in MUSI-1306 music appreciation courses study many composers and compositions. Of those composers, music appreciation textbooks typically briefly mention a few women composers, most notably Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel and Clara Schumann. Most music courses focus on the master composers comprised of men. This lack of representation of women composers in music appreciation textbooks creates the illusion that there have not been many women performers or composers. Many women engaged in these musical activities. While many female musicians only performed or composed for family and friends, many others performed publicly and regularly published their works. Music appreciation curricula should convey a more diverse population of composers by integrating the study of compositions written by women to achieve the learning objectives for the course. There are similar objectives used throughout MUSI- 1306 college-level music appreciation courses across the state of Texas. In these classes, students learn to identify musical works and elements in a variety of styles, analyze the elements and structure of music using appropriate terminology, and critically evaluate the influence of social, political, technological, or cultural ideas on music. Educators should offer a more diverse compilation of works that would include women composers. Compositions written by women can fulfill the overall objectives in a music course just as well as using works written by men. -

Gendered Musical Responses to First World War Experiences Abstract

Gendered Musical Responses to First World War Experiences Abstract This article investigates how women composers have responded to and commemorated the First World War. It juxtaposes works written between 1915 and 1916 by Susan Spain-Dunk, Morfydd Owen and Adela Maddison, with contemporary responses as part of the centenary commemorations (2014-18) by Cecilia MacDowall, Catherine Kontz and Susan Philipz. Pierre Nora’s concept of ‘sites of memory’, Benedict Anderson’s ‘imagined communities’ and Judith Butler’s theory of mourning provide a framework in order to analyse the different functions of this music in terms of our collective memory of the War. The article ultimately argues that this music contributes to a re-evaluation of how female composers experience the cultural impact of the War. By anachronistically discussing these stylistically disparate works alongside one another, there is the possibility of disrupting the progressively linear canonical musical tradition. In August 1914, London’s musical society was taken by surprise at the outbreak of war. As it was outside the main concert season, only the Proms concerts, then held at the Queen’s Hall, had to immediately consider their programming choices. On 15 August the decision was taken to cancel a performance of Strauss, and two days later an all Wagner-programme was replaced with works by Debussy, Tchaikovsky and a rendition of the Marseillaise.1 This instigated a debate in the musical press, which continued throughout the War, questioning nationalistic tendencies in music, the role of musicians in wartime, and how the War would influence musical composition. Meanwhile, women’s music, which had increasingly gained currency from the early twentieth century, continued with some vibrancy throughout the War, albeit often in non-mainstream venues and private contexts. -

The Organ Music of Ethel Smyth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks THE ORGAN MUSIC OF ETHEL SMYTH: A GUIDE TO ITS HISTORY AND PERFORMANCE PRACTICE BY SARAH M. MOON Submitted to the faculty of the School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music, Indiana University May, 2014 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music. __________________________________ Janette Fishell, Research Director __________________________________ Gretchen Horlacher __________________________________ Bruce Neswick __________________________________ Christopher Young ii Copyright © 2014 Sarah M. Moon iii This document is dedicated to my family. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would foremost like to thank the members of my Doctoral Committee: Professor Janette Fishell, Professor Gretchen Horlacher, Professor Bruce Neswick, and Professor Christopher Young. I truly appreciate my five years at Indiana University under their guidance and admire their inspirational models of character and excellence. I would especially like to thank Dr. Janette Fishell, my organ professor and research director, who has provided invaluable musical and academic encouragement. I am also grateful to many people and institutions in England who helped with my research: Fiona McHenry and the helpful staff at the British Library’s Music and Rare Books Reading Room; Michael Mullen and the librarians at the Royal College of Music; Peter Graham Avis, a fellow Ethel Smyth scholar; and Alex Joannides from Boosey and Hawkes for granting me permission to make a copy of “Prelude on a Traditional Irish Air” for study purposes. -

Heinrich Von Herzogenberg's "Zwei Biblische Scenen": a Conductor's Study

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1999 Heinrich Von Herzogenberg's "Zwei Biblische Scenen": a Conductor's Study. John Elbert Boozer Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Boozer, John Elbert, "Heinrich Von Herzogenberg's "Zwei Biblische Scenen": a Conductor's Study." (1999). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 7036. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/7036 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor qualify illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Ethel Smyth: a Life of Music and Activism

Ethel Smyth: A Life of Music and Activism As musician Sir Thomas Beecham, friend to Ethel Smyth, walked into the prison yard at Holloway Prison to visit her, he came upon the scene of dozens of suffragettes marching and singing their war-chant, its opening cry: Shout, shout, up with your song! Cry with the wind, for the dawn is breaking; March, march, swing you along, Wide blows our banner, and hope is waking. Ethel Smyth stood in her jail cell, the voices of the women rising up to her. They were singing her song, The March of the Women (words by Cicely Hamilton), composed a year earlier in 1911 as the anthem for the Women's Social and Political Union. Inspired, she stretched her arms out beyond the window bars and, in the Portrait of Ethel Smyth, 1901, words of Sir Beecham, ". beaming approbation from an overlooking upper by John Singer Sargent window, beat time in almost Bacchic frenzy with a toothbrush." The preceding anecdote illustrates the quintessential Ethel Smyth. The feisty, at times radical, activist fought not only for voting rights for women, but also for the equality of women musicians in the male-dominated milieu that was, and is, classical music. (In today's top 20 U.S. major orchestras in 2014, 91% of conductors/music directors and 63% of musicians were male, with men holding 69% of the [higher-paying] principal positions, and 82% of the concertmaster positions while only comprising 41% of all violinists. [1] Of the compositions performed by the top 21 orchestras in the 2014 – 2015 orchestral season, only 1.8% overall were composed by women, with 14.8% of living composers' compositions being by women. -

Dame Ethel Smyth and the Prison: Gender, Sexuality, and the "Bonds of Self"

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2021 Dame Ethel Smyth and The Prison: Gender, Sexuality, and the "Bonds of Self" Mary Shannon Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Shannon, Mary, "Dame Ethel Smyth and The Prison: Gender, Sexuality, and the "Bonds of Self"" (2021). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1628. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1628 This Honors Thesis -- Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Composers often draw on various identities and experiences in their work in order to position their compositions within real-world events and their personal lives. This research investigates the use of personal gender and sexuality references in Ethel Smyth’s composition The Prison. Smyth’s last major work, The Prison (1929-1930), is a choral symphony that follows a dialogue between a Prisoner and his Soul as the Prisoner works to understand his own mortality and accept death. This study explores the question: How does Ethel Smyth use intertextuality, the subversion of expectations, and the idea of the “bonds of self” in The Prison to position the work within her gender and sexuality experiences? A focus is placed on the sociolinguistic notions of identity and desire, seeking to discover how the combination of homosexuality and female gender influence the work. -

Dame Ethel Smyth's Concerto for Violin, Horn, and Orchestra: a Performance Guide for the Hornist

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 Dame Ethel Smyth's Concerto for Violin, Horn, and Orchestra: A Performance Guide for the Hornist. Janiece Marie Luedeke Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Luedeke, Janiece Marie, "Dame Ethel Smyth's Concerto for Violin, Horn, and Orchestra: A Performance Guide for the Hornist." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6747. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6747 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

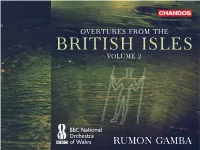

British Isles Volume 2

includes premiere recording OVERTURES FROM THE BRITISH ISLES VOLUME 2 RUMON GAMBA Roger Quilter Photograph by Herbert Lambert © Royal Academy of Music / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Overtures from the British Isles, Volume 2 Sir William Walton (1902 – 1983) 1 Portsmouth Point (1924 – 25) 5:33 Overture Robusto – Full and broad Walter Leigh (1905 – 1942) 2 Agincourt (1935) 12:29 (Jubilee Overture) Overture for Orchestra Edited by Malcolm Riley (b. 1960) Allegro con brio – Andante – Maestoso – Allegro con brio (Tempo I) York Bowen (1884 – 1961) premiere recording 3 Fantasy Overture, Op. 115 (1945) 8:27 for Orchestra With acknowledgements to Tom Bowling To Meyer de Wolfe, 1945 Allegro con spirito – Poco più sostenuto – Tempo I – Poco più sostenuto – Tempo I – Maestoso 3 Dame Ethel Smyth (1858 – 1944) 4 Overture to ‘The Boatswain’s Mate’ (1913 – 14) 6:05 Comedy in One Act Allegro John Ansell (1874 – 1948) 5 Plymouth Hoe (1914) 7:57 A Nautical Overture Allegro con brio – Andante – Poco più mosso – Tempo I – Poco animato – Tempo I Sir Alexander Campbell Mackenzie (1847 – 1935) 6 Britannia, Op. 52 (1894) 7:37 A Nautical Overture Dedicated by permission to His Royal Highness The Duke of Saxe Coburg and Gotha K.G. Lento – Allegro vivace – Largamente – Presto – Largamente 4 Eric Coates (1886 – 1957) 7 The Merrymakers (1923) 4:54 Miniature Overture Molto vivace – Grazioso – Appassionato – Brillante – Tempo I – Broadly – Allegro molto Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848 – 1918) 8 Overture to an Unwritten Tragedy (1893, revised 1894, 1905) 12:29 for Orchestra Lento – Allegro energico Roger Quilter (1877 – 1953) 9 A Children’s Overture, Op. -

Composer Timeline Er N Ag Eth W El S D M R 1750 1800 1850 1900 1950 Y 2000 a T H H C

Composer Timeline er n ag Eth W el S d m r 1750 1800 1850 1900 1950 y 2000 a t h h c i Joseph Haydn (Austrian) 1732-1809 R Claude Debussy (French) 1862-1918 gar El rd a w Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austrian) 1756-1791 Franz Schubert (Austrian) 1797-1828 Edward Elgar (British) 1857-1934 d E Ludvig van Beethoven (German) 1770-1827 Ethel Smyth (British) 1858-1944 Jos eph H Fanny Mendelssohn (German) 1805-1847 Amy Beach (American) 1867-1944 a y d e Amadeu Frédéric Chopin (Polish) 1810-1849 Arnold Franz Schoenberg (Austrian) 1874-1951 n ang s M fg o pin l za o o r h W t C Louise Farrenc (French) 1804-1875 Aaron Copland (American) 1900-1990 ic r é d é r Richard Wagner (German) 1813-1883 Dmitri Shostakovich (Russian) 1906-1975 F Clar a S ch Clara Schumann (German) 1819-1896 John Cage (American) 1912-1992 u ethoven m Be n a a n Richard Strauss (German) 1825-1899 Benjamin Britten (British) 1913-1976 v n g i v d Johannes Brahms (German) 1833-1897 Karlheinz Stockhousen (German) 1928-2007 u yotr Ily L P ic h Tc Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (Russian) 1840-1893 h a i k o Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (Russian) 1844-1908 v s k y Classical Early Romantic Late Romantic 20th Century Composer Timeline er n ag Eth W el S d m r 1750 1800 1850 1900 1950 y 2000 a t h h c i Joseph Haydn (Austrian) 1732-1809 R Claude Debussy (French) 1862-1918 gar El rd a w Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austrian) 1756-1791 Franz Schubert (Austrian) 1797-1828 Edward Elgar (British) 1857-1934 d E Ludvig van Beethoven (German) 1770-1827 Ethel Smyth (British) 1858-1944 Jos eph H Fanny Mendelssohn -

Dame Ethel Smyth: Pioneer of English Opera Eugene Gates

Volume 11, Issue 1 The Kapralova Society Journal Spring 2013 A Journal of Women in Music Dame Ethel Smyth: Pioneer of English Opera Eugene Gates “I feel I must fight for [my music], because I lieved that her musical instincts were inher- want women to turn their minds to big and ited from her mother, whom she once de- difficult jobs; not just to go on hugging the scribed as “one of the most naturally musical shore, afraid to put out to sea.” 1 When Ethel people I have ever known.” 7 Smyth wrote these words in the early years of Ethel’s general education was typical of her career, she had little idea of the protracted that of a middle-class Victorian young lady. battle against prejudice that lay ahead of her. After private tutoring at home under the guid- Smyth was certainly not England’s first ance of a succession of governesses, she woman composer. But while most of her spent a few years in boarding school at Put- predecessors, because of social circumstances ney, where the prescribed curriculum in- and limited training, had been forced to con- cluded French, German, astronomy, chemis- fine their creative endeavours to the production try, mathematics, literature, history, drawing, of parlor music, she set her sights on the con- music, and home economics. 8 Very little is Special points of interest: quest of the opera house and concert stage. Her known about Smyth’s early musical training. published works include six operas, a concert In her memoirs, however, she mentions a mass, a double concerto, a choral symphony, governess who introduced her to classical • Ethel Smyth and English opera songs with piano and orchestral accompa- music, and inspired her to set her sights on a niment, organ pieces and chamber music.