A Landscape Analysis of Fortification in Tamil Nadu Using Satellite Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telephone Numbers

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY THANJAVUR IMPORTANT TELEPHONE NUMBERS DISTRICT EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTRE THANJAVUR DISTRICT YEAR-2018 2 INDEX S. No. Department Page No. 1 State Disaster Management Department, Chennai 1 2. Emergency Toll free Telephone Numbers 1 3. Indian Meteorological Research Centre 2 4. National Disaster Rescue Team, Arakonam 2 5. Aavin 2 6. Telephone Operator, District Collectorate 2 7. Office,ThanjavurRevenue Department 3 8. PWD ( Buildings and Maintenance) 5 9. Cooperative Department 5 10. Treasury Department 7 11. Police Department 10 12. Fire & Rescue Department 13 13. District Rural Development 14 14. Panchayat 17 15. Town Panchayat 18 16. Public Works Department 19 17. Highways Department 25 18. Agriculture Department 26 19. Animal Husbandry Department 28 20. Tamilnadu Civil Supplies Corporation 29 21. Education Department 29 22. Health and Medical Department 31 23. TNSTC 33 24. TNEB 34 25. Fisheries 35 26. Forest Department 38 27. TWAD 38 28. Horticulture 39 29. Statisticts 40 30. NGO’s 40 31. First Responders for Vulnerable Areas 44 1 Telephone Number Officer’s Details Office Telephone & Mobile District Disaster Management Agency - Thanjavur Flood Control Room 1077 04362- 230121 State Disaster Management Agency – Chennai - 5 Additional Cheif Secretary & Commissioner 044-28523299 9445000444 of Revenue Administration, Chennai -5 044-28414513, Disaster Management, Chennai 044-1070 Control Room 044-28414512 Emergency Toll Free Numbers Disaster Rescue, 1077 District Collector Office, Thanjavur Child Line 1098 Police 100 Fire & Rescue Department 101 Medical Helpline 104 Ambulance 108 Women’s Helpline 1091 National Highways Emergency Help 1033 Old Age People Helpline 1253 Coastal Security 1718 Blood Bank 1910 Eye Donation 1919 Railway Helpline 1512 AIDS Helpline 1097 2 Meteorological Research Centre S. -

Economic and Cultural History of Tamilnadu from Sangam Age to 1800 C.E

I - M.A. HISTORY Code No. 18KP1HO3 SOCIO – ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF TAMILNADU FROM SANGAM AGE TO 1800 C.E. UNIT – I Sources The Literay Sources Sangam Period The consisted, of Tolkappiyam a Tamil grammar work, eight Anthologies (Ettutogai), the ten poems (Padinen kell kanakku ) the twin epics, Silappadikaram and Manimekalai and other poems. The sangam works dealt with the aharm and puram life of the people. To collect various information regarding politics, society, religion and economy of the sangam period, these works are useful. The sangam works were secular in character. Kallabhra period The religious works such as Tamil Navalar Charital,Periyapuranam and Yapperumkalam were religious oriented, they served little purpose. Pallava Period Devaram, written by Apper, simdarar and Sambandar gave references tot eh socio economic and the religious activities of the Pallava age. The religious oriented Nalayira Tivya Prabandam also provided materials to know the relation of the Pallavas with the contemporary rulers of South India. The Nandikkalambakam of Nandivarman III and Bharatavenba of Perumdevanar give a clear account of the political activities of Nandivarman III. The early pandya period Limited Tamil sources are available for the study of the early Pandyas. The Pandikkovai, the Periyapuranam, the Divya Suri Carita and the Guruparamparai throw light on the study of the Pandyas. The Chola Period The chola empire under Vijayalaya and his successors witnessed one of the progressive periods of literary and religious revival in south India The works of South Indian Vishnavism arranged by Nambi Andar Nambi provide amble information about the domination of Hindu religion in south India. -

District Survey Report for Gravel Thanjavur District Tamilnadu State

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT FOR GRAVEL THANJAVUR DISTRICT TAMILNADU STATE (Prepared as per Gazette Notification S.O.3611 (E) dated 25.07.2018 of Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change) MAY 2019 Page 1 Page 2 Chapter Content Page No. 1. Introduction 5 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District 5 3. General Profile of the District 6 4. Geology of Thanjavur District 10 5. Drainage of Irrigation pattern 14 6. Land Utilisation Pattern in the District: Forest, 16 Agricultural, Horticultural, Mining etc., 7. Surface Water and Ground Water scenario of the 16 District 8. Climate and Rainfall of the District 22 9. Details of Mining Leases of Gravel in the District 23 10. Details of Royalty or Revenue collected for Gravel in 25 last three years 11. Details of Production of Gravel in last three years 25 12. Mineral Map of the District 26 13. List of Leases of Gravel in the District along with its 31 validity 14. Total Mineral Reserve available in the district 33 15. Quality/Grade of Mineral available in the district 35 16. Use of Mineral 35 17. Demand and supply of the Mineral in the last three 35 years 18. Mining Leases marked on the map of the district 35 19. Details of the area of where there is a cluster of the 37 mining leases 20. Details of Eco-sensitive area 37 21. Impact on the environment due to Mining activity 38 22. Remedial measures to mitigate the impact of mining 40 on the environment 23. Reclamation of the mined out area 42 24. -

Thanjavur District

THANJAVUR DISTRICT 1 THANJAVUR DISTRICT 1. Introduction Number of taluks 8 i) Geographical location of the district Number of revenue 906 villages Thanjavur district lies between 9º 50’ and 11º 25’ North latitude and 78º 45’ and Revenue Taluk 79º 25’ East longtitude. It is bounded on the villages North by Thiruchirapalli and Cuddalore districts, on the East by Tiruvarur and Kumbakonam 124 Nagapattinam districts, on the South by Palk Orathanadu 125 Strait and Pudukottai district and on the west by Pudukkottai district and Tiruchirapalli Papanasam 120 districts. Total geographical area of the district is 3,602.86 sq.km. This constitutes Pattukkottai 175 just 2.77 % of the area of the State. Peravurani 91 ii) Administrative profile Thanjavur 93 Administrative profile of the district Thiruvaiyaru 89 is given in the table below. Thiruvidaimarudur 89 iii) Meteorological information The mean maximum temperature was 37.48ºC during May – July. Similarly, the mean minimum temperature was 20.82ºC during November-January. The north east monsoon provides much rainfall with 545.7 mm and 953.2 as normal and actual rainfall respectively, while southwest monsoon provides 342 and 303.1 mm as normal and actual rainfall respectively. During May, dust storms, whirlwinds and dusty winds flow from various directions. The south west winds that set in during April, become strong in June and continue till September Cyclonic storms of high velocity affect the district once in 3 or 4 years during November - December. 2 2. Resources availability monsoon and to accommodate two crops namely Kuruvai and Thaladi. i) Agriculture and horticulture Thanjavur district stands unique from The soils of new deltaic area are time immemorial for its agricultural amenable to a wide variety of crops such as activities and is rightly acclaimed as the coconut, mango, guava, pulses, cotton, granary of South India lying in the deltaic gingelly, groundnut, banana etc. -

53067-004: Inclusive, Resilient, and Sustainable Housing for Urban

Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Draft for Consultation Project Number: 53067-004 January 2021 IND: Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Housing for Urban Poor Sector Project in Tamil Nadu Subproject: Construction of 969 Nos of housing units adopting Type Design No. 02/2020 (G+5) with associated infrastructure works at Vallam Vadaku Sethi Village, Thanjavur Taluk in Thanjavur District (IRSHUP/VAL/03) Prepared by the Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board, Government of Tamil Nadu for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 22 January 2021) Currency Unit – Indian rupee (₹) ₹1.00 = $ 0.0137 $1.00 = ₹73.038 ABBREVIATIONS ADB - Asian Development Bank BPL - below poverty Line CCDO - Chief Community Development Officer CBO - community based organization EMA - external monitoring agency GOTN - Government of Tamil Nadu IRSHUPSP - Inclusive, Resilient and Sustainable Housing for the Urban Poor Sector Project NGO - non-governmental organization PID - project implementation division PMU - project management unit SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TNSCB - Tamil Nadu Slum Clearance Board TNPTEEA - Tamil Nadu Protection of Tanks and Eviction of Encroachment Act TWAD - Tamil Nadu Water Supply and Drainage Board WBM - Water Bound Macadam NOTE In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Thanjavur District Industrial Profile 2020-21

Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Government of India Thanjavur District Industrial Profile 2020-21 Prepared by MSME Development Institute - Chennai Office of the Development Commissioner Ministry of Micro Small and Medium Enterprises Government of India INDEX CHAPTER CONTENT PAGE NO. 1 DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 4 2 INTRODUCTION 10 3 AVAILABLITY OF RESOURCES 16 4 INFRASTRUCTURE FACILITY EXISTING IN 23 THANJAVUR 5 INDUSTRIAL SCENARIO AND MSMEs AT 25 THANJAVUR 6 MICRO SMALL ENTERPRISES- CLUSTER 33 DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 7 SWOT ANALYISIS FOR ENTERPRISES 36 DEVELOPMENT 8 INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT FOR MSMEs 37 9 STEPS TO SET UP ENTERPRISES 44 10 IMPORTANT SCHEMES AND ITS PERFORMANCE 59 11 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ANNEXURE- ADDRESSESS OF CENTRAL AND STATE GOVT 67 I AUTHORITIES ANNEXURE- IMPORTANT CONTACTS IN THANJAVUR 71 II 2 DISTRICT MAP - THANJAVUR DISTRICT 3 CHAPTER-I THANJAVUR DISTRICT AT A GLANCE 1. PHYSICAL & ADMINISTRATIVE FEATURES Total Geographical Area (Sq.km) 3397 Division Taluks Thanjavur 1 Thanjavur 2 Orathanadu 3 Thiruvaiyaru 4 Budalur Kumbakonam 5 Kumbakonam 6 Papanasam 7 Thiruvidaimaruthur Pattukottai 8 Pattukottai 9 Peravurani Firkas 50 Revenue Villages 906 2. SOIL & CLIMATE Agro-climatic Zone Humid Tropical climate, Zone XI Climate Hot & Humid Soil Type Mainly alluvial 3. LAND UTILISATION [Ha] - (DSH - 2013-14) Total Area Reported 339657 Forest Land 3390 Area Not Available for Cultivation 83879 Permanent Pasture and Grazing Land 1218 Land under Miscellaneous Tree Crops 5337 Cultivable Wasteland 12097 Current Fallow 17943 Other Fallow 28458 Net Sown Area 187335 Total or Gross Cropped Area 267747 Area Cultivated More than Once 80412 Cropping Inensity [GCA/NSA] 143 4 4. RAINFALL & GROUND WATER (DSH - 2013-14) Rainfall [in Normal Actual 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 mm] 1013 874 757 756 Variation from -13.7% -25.3% -25.4% Normal Availability Net Net Balance of Ground annual annual Water [Ham] recharge draft 73605 52788 20817 5. -

Dr. P. Vembarasi, Associate Professor of History, K.N.Govt

DR. P. VEMBARASI, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY, K.N.GOVT. COLLEGE (W), THANJAVUR. SOUTH INDIAN HISTORY CONGRESS SNO NAME OF TITLE OF THE ARTICLE SPONSORS AND THE AUTHOR PUBLISHERS 1 Dr. P.Vembarasi Historical Importance of 34th Annual Session Proceedings, Palaiyarai South Indian History Congress, A.V.V.M. Pushpam College Poondi. 28th February-2nd March, 2014. TAMIL NADU HISTORY CONGRESS SNO NAME OF TITLE OF THE ARTICLE SPONSORS AND THE AUTHOR PUBLISHERS 1 15th Annual Session, Tamil Nadu Dr. P.Vembarasi Travels of Serfoji-II –A study History Congress, Periyar Maniyammai University, Vallam. 19th-21st September, 2008 JOURNALS NAME OF THE TITLE OF THE SNO AUTHOR ARTICLE NAME OF THE JOURNAL Pilgrimage and Indian Tamil Pozhil(Tamil Research 1 P.Vembarasi Integrity Journal)April 2007 Serfoji and Saraswathi Mahal Tamil Pozhil (Tamil 2 P.Vembarasi Library Research Journal)May 2007 Tamil Pozhil (Tamil Research 3 P.Vembarasi Tourism in Literature Journal) Dec2007 Origin and Growth Tamil Pozhil (Tamil Research 4 P.Vembarasi of Tourism Journal) Jan2008 Travels of Serfoji II – A Tamil Pozhil (Tamil Research 5 P.Vembarasi Study Journal) Mar 2008 Tamil Pozhil (Tamil Research 6 P.Vembarasi Significance of Rameswaram Journal) Mar 2008 Raja Serfoji II in Tanjore 7 Dr.P.Vembarasi Senthamil National Journal May 2009 History Pilgrimage of Raja Serfoji II 8 Dr.P.Vembarasi Senthamil National Journal May 2009 – A Study Rameswaram in Historical 9 Dr.P.Vembarasi Senthamil National Journal May 2009 Perspectives Progress of Science under Scientific Tamil State, published by 10 Dr.P.Vembarasi Ancient Greeks Government of Tamil Nadu INTERNATIONAL SEMINARS SNO NAME OF THE TITLE OF THE SPONSORS AND AUTHOR ARTICLE PUBLISHERS 1 Dr. -

Interpretation of Soil Resources Using Remote Sensing and GIS in Thanjavur District, Tamil Nadu, India

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2011, 2 (3): 525-535 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Interpretation of soil resources using remote sensing and GIS in Thanjavur district, Tamil Nadu, India J. Punithavathi*, S. Tamilenthi and R. Baskaran Department of Industries and Earth Sciences, Tamil University, Thanjavur, TN, India ______________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Mapping of physiographic units and the sediments/soils of an area can give useful information for land use planning. Remote sensing technique plays an important role in the mapping of soil, physiographic units and other land resources. In this present study, Thanjavur district, Tamil Nadu has been choosen to prepare physiographic units and soil maps by using IRS-P6 satellite imagery, (Scale 1:50,000). This study reveals that the mapping of different soil/sediment types and physiographic units can be effectively and the land suitability can be inferred. Key words: Physiographic units, Soil productivity, Crops grown, Remote sensing and GIS. ______________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION In view of soil resources mapping, the study area of Thanjavur district Tamil nadu has been interpreted. The Remote sensing Technique is a major tool interpreting the land resources and that can be used for a Thanjavur area like this kind of soil mapping. The major physiographic features such as alluvial and sandy plains, undulating pediplan, upland and natural vegetation, coastal plain areas or low lying lands of the study area have been interpreted. There are many previous investigation such as Ahuja R.L[1], Kumar, Ashok and Sanjay Kumar Srivastava [3], Fabos J.G.[4], Fitz and Patrick.E.A [5], Lillesand, Keieper[6], Saha and S.K.Singh [7] and many other soil resources related of the previous investigation. -

List of Polling Stations for 174 Thanjavur Assembly Segment Within the 30 Thanjavur Parliamentary Constituency

List of Polling Stations for 174 Thanjavur Assembly Segment within the 30 Thanjavur Parliamentary Constituency Sl.No Polling Location and name of building in Polling Areas Whether for All station No. which Polling Station located Voters or Men only or Women only 12 3 4 5 1 1 Municipal Middle School Old 1.Thanjavur (M) Agilambal pettai kadai street ward-1 , 2.Thanjavur (M) All Voters Building West Portion Palliyagraharam Road Ward-1 , 3.Thanjavur (M) Palliagraharam West street Ward-1 ,Palliagraharam 613003 , 4.Thanjavur (M) Palliyagraharam North street Ward-1 , 5.Thanjavur (M) Palliyagraharam East Street Ward-1 , 6.Thanjavur (M) Palliyagraharam middle street Ward-1 , 7.Thanjavur (M) Panjanatham Pillai lane Ward-1 , 8.Thanjavur (M) Jambu Kaveri Street Ward-1 2 2 Municipal Middle School Old 1.Thanjavur (M) Palliyagraharam South street ward-1 , 2.Thanjavur (M) All Voters Building (South Portion) Kumbakonam Road Ward-1 , 3.Thanjavur (M) Adidravidar street Ward-1 , ,Palliagraharam 613003 4.Thanjavur (M) Palliyagraharam Chinna Adidravidar street Ward 1 , 5.Thanjavur (M) Sathiya Krishna Nagar Ward-1 3 3 Sri Krishna Padasalai Elementary 1.Thanjavur (M) Anandhavalli Amman Kovil North lane ward-1 , 2.Thanjavur (M) All Voters School ,Vennatrankarai 613003 Anandhavalli Amman Kovil south street Ward-1 , 3.Thanjavur (M) Anna Chathiram Kadai street Ward-1 , 4.Thanjavur (M) Vijaya Ragavachariyar Road Ward-1 , 5.Thanjavur (M) Singaperumal Kovil North Street Ward-1 , 6.Thanjavur (M) Singaperumal Kovil Sannathi street Ward-1 , 7.Thanjavur (M) Singaperumal -

![316] CHENNAI, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2011 Aavani 22, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9055/316-chennai-thursday-september-8-2011-aavani-22-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2042-4179055.webp)

316] CHENNAI, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2011 Aavani 22, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2009-11. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2011 [Price: Rs. 140.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 316] CHENNAI, THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 8, 2011 Aavani 22, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2042 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFICATIONS BY GOVERNMENT RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND PANCHAYAT RAJ DEPARTMENT RESERVATION OF OFFICES OF CHAIRPERSONS OF PANCHAYAT UNION COUNCILS FOR THE PERSONS BELONGING TO SCHEDULED CASTES / SCHEDULED TRIBES AND FOR WOMEN UNDER THE TAMIL NADU PANCHAYAT ACT [G.O. Ms. No. 56, Rural Development and Panchayat Raj (PR-1) 8th September 2011 ÝõE 22, F¼õœÀõ˜ ݇´ 2042.] No. II(2)/RDPR/396(e-1)/2011. Under Section 57 of the Tamil Nadu Panchayat Act, 1994 (Tamil Nadu Act 21 of 1994) the Governor of Tamil Nadu hereby reserves the offices of the Chairpersons of Panchayat Union Council for the persons belonging to Scheduled Castes / Scheduled Tribs and for Women as indicated below: The Chairpersons of the Panchayat Union Councils. DTP—II-2 Ex. (316)—1 [ 1 ] 2 TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY RESERVATION OF SEATS OF CHAIRPERSONS OF PANCHAYAT UNION Sl. Panchayat Union Category to Sl. Panchayat Union Category to which No which Reservation No Reservation is is made made 1.Kancheepuram District 4.Villupuram District 1. Thiruporur SC (Women) 1 Kalrayan Hills ST (General) 2. Acharapakkam SC (Women) 2 Kandamangalam SC(Women) 3. Uthiramerur SC (General) 3 Merkanam SC(Women) 4. Sriperumbudur SC(General) 4 Ulundurpet SC(General) 5. -

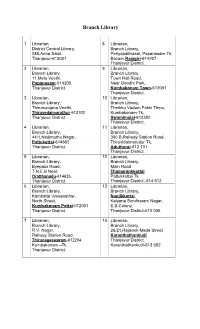

Branch Library

Branch Library 1 Librarian, 8 Librarian, District Central Library, Branch Library, 286,Anna Salai, Periyapallivasal, Papanasam-Tk, Thanjavur-613001 Bazaar,Rajagiri-614207. Thanjavur District. 2 Librarian, 9 Librarian, Branch Library, Branch Library, 11,Mela Veethi, Town Hall Road, Papanasam-614205. Near Gandhi Park, Thanjavur District. Kumbakonam Town-612001 Thanjavur District. 3 Librarian, 10 Librarian, Branch Library, Branch Library, Thirumanjana Veethi, Therkku Vadam,Pokki Theru, Thiruvedaimaruthur-612103 Kumbakonam-Tk, Thanjavur District. Swamimalai-612302. Thanjavur District. 4 Librarian, 11 Librarian, Branch Library, Branch Library, 44/1,Nadimuthu Nagar, 306 B,Railway Station Road, Pattukottai-614602 Thiruvidaimarudur Tk Thanjavur District. Aduthurai-612 101 Thanjavur District. 5 Librarian, 12 Librarian, Branch Library, Branch Library, Byepass Road, Main Road T.N.E.B Near, Thamarankkottai Oratthanadu-614625. Pattukkottai Tk Thanjavur District. Thanjavur District.-614 613 6 Librarian, 13 Librarian, Branch Library, Branch Library, Kambatta Viswanathar, Nanjikkottai, North Street, Kalyana Sundharam Nagar, Kumbakonam Pettai-612001 E.B.Colony, Thanjavur District. Thanjavur District-613 006. 7 Librarian, 14 Librarian, Branch Library, Branch Library, R.V. Nagar, 26/21,Rajaram Mada Street Railway Station Road, Karanthathankudi Thirunageswaram-612204 Thanjavur District. Kumbakonam –Tk, Karanthathankudi-613 002 Thanjavur District. 15 Librarian, 23 Librarian, Branch Library, Branch Library, 1661, Krishnan Kovil 1st St, Kamarajar Salai, Manambhuchavadi -

Detecting Land Use and Land Cover Changes of Thanjavur Block in Thanjavur District, Tamilnadu, India from 1991 to 2009 Using Geographical Information System

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2012, 3 (2):986-993 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Detecting land use and land cover changes of Thanjavur block in Thanjavur district, Tamilnadu, India from 1991 to 2009 using geographical information system J. Punithavathi 1, S.Tamilenthi 1*, R. Baskaran 2 and R. Mahesh 3 1Research scholar, Department of Earth Science, Tamil University, Thanjavur, India 2Department of Earth Science, Tamil University, Thanjavur, India 3SASTRA University, Thanjavur, India ______________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Land use and land cover is dominant role in the part of urbanization. As the rapid urbanization led various activities in a region and these changes generally takes place in the agricultural land and caused decrease of arable land .The satellite imageries LANDSAT 5TM (1991), LANDSAT 7ETM (1999) AND LISS 111 (2009) data’s are used. The scales are 1:50,000 and 1:250,000. 1991, 1999 and 2009 covering a period of 19 years the aerial distribution of the land use and land cover changes has been observed. The changes were identified ,in which the decrease of Agricultural land, Mixed plantation, Scrub land and Water body and increase of Built up land, Fallow land, River sand and Without scrub land. The land use and land cover maps are prepared by using GIS software to evaluate the changes and it is showed strong variation. Key words: Land use and land cover, urbanization, Thanjavur block and GIS. ______________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION Land is the basic resources of human society. It is the most significant among the natural resources of the country and most of its inhabitants depend on agriculture for their livelihood.