Turkey's Future Transitions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COULD POVERTY BE TURNED INTO PROSPERITY and POOR INTO RICH in TURKEY’S REALITY? Asst

Niğde Üniversitesi, İ.İ.B.F. Dergisi, 2010, Cilt:3, Sayı:2, s.135-161. 135 COULD POVERTY BE TURNED INTO PROSPERITY and POOR INTO RICH IN TURKEY’S REALITY? Asst. Assoc. Dr. Haldun SOYDAL1 Asst. Assoc. Dr. Serkan GÜZEL2 Res. Assist. M. Göktuğ KAYA3 ABSTRACT Arguments not only over the poverty of individuals but also over the poverty of groups, communities, nations, and countries have begun to make several kind of poverties, including individualistic, economical, regional, cultural, the main point of the escalating studies. In this sense, the main aim of this paper representing a significant indicator for studies mentioned above is determining the concept of poor and poverty, unveiling underlying factors of poverty and putting forth how to cope with poverty. One the the most crucial result of this paper highlighting the role of Turkey‟s policy that make inequality of income distribution, black economy and irregularity legislative is closely linked with the political conciousness that will be able to turn poverty into prosperity in general and poor into rich in particular in the reality of Turkey, via distributing internal revenue as regards contribution of individuals, groups, social classes and via improving national capital. Keywords: Poverty, Poor, Poverty Line, Struggle Against Poverty. JEL Codes: I38, A14, H11 ÖZET Sadece bireylerin değil aynı zamanda grup, topluluk, ulus ve ülkelerin yoksulluğu üzerine tartıĢmalar, bireysel, ekonomik, bölgesel, kültürel pek çok yoksulluk çeĢidini giderek artan çalıĢmaların temel hareket noktası haline getirmeye baĢlamıĢtır. Bu anlamda sözü edilen çalıĢmalara anlamlı bir gösterge oluĢturan bu çalıĢmanın temel amacı, yoksul ve yoksulluk kavramlarını saptamak, yoksulluğun nedenlerini açığa çıkarmak ve yoksulluğun üstesinden nasıl gelineceğini öne sürmektir. -

Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in Forest

Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in the Forest Communities of Turkey Evidence and policy impact analysis POVERTY, FOREST DEPENDENCE AND MIGRATION IN THE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF TURKEY A B POVERTY, FOREST DEPENDENCE AND MIGRATION IN THE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF TURKEY Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in the Forest Communities of Turkey Evidence and policy impact analysis JUNE, 2017 Acknowledgements This paper was prepared by a combined team1 of World Bank staff and consultants, working with local Turkish consultants and stakeholders in close collaboration.2 The team would like to acknowledge the efforts of UDA Consulting in Turkey for the survey’s design and implementation. The team would like to acknowledge the support and design contributions of the Program for Forests (PROFOR), who also funded this study. Additionally, the team would like to acknowledge the cooperation of the General Directorate of Forestry (GDF), who provided guidance and the oversight of information that led to the construction of the survey and sample design. The findings from this paper form an integral part of a much broader engagement with the Turkish GDF through a jointly-produced Forest Policy Note. 1 The Team comprised: Craig M. Meisner (World Bank, Task Team Leader and Sr Environmental Economist), Limin Wang (World Bank, Consultant), Raisa Chandrashekhar Behal (World Bank, Consultant), and Priya Shyamsundar (World Bank, Consultant), Andrew Mitchell (World Bank, Sr Forestry Specialist), and Esra Arikan (World Bank, Sr Environmental Specialist). 2 Local Turkish collaborators included: UDA Consulting for survey implementation and the Central Union of Turkish Forestry Cooperatives (OR-KOOP). CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. -

Intertemporal Poverty in Turkey

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Procedia Economics and Finance 30 ( 2015 ) 487 – 497 3rd Economics & Finance Conference, Rome, Italy, April 14-17, 2015 and 4th Economics & Finance Conference, London, UK, August 25-28, 2015 Intertemporal poverty in Turkey Ömer Limanlıa,* a Artvin Çoruh University, Artvin 08600, Turkey Abstract Poverty is generally considered as a static fact. Economics literature caters us several poverty indexes that measure aggregate poverty from cross-sectional data sets. These cross-sectional data sets and poverty indexes would not provide any information about the dynamic side of poverty. Some households/people might stay poor longer than others, some households/people might move to certain poverty line from the bottom part of income distribution while the others might stay at the bottom part of income distribution forever. Early poverty indexes are insensitive to these aspects of poverty. Taking into account these all, in this study, we have investigated about the intertemporal poverty in Turkey. We have used newly developed intertemporal poverty indexes and estimated the determinants of staying poor in Turkey by using panel data set Income and Living Conditions Survey for 2006-2009 . In accordance with the final results, some economic policy recommendations are given to solve the poverty issue in Turkey. © 20152015 TheThe Authors. Authors. Published Published by by Elsevier Elsevier B.V. B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Peer-review under responsibility of IISES-International Institute for Social and Economics Sciences. Peer-review under responsibility of IISES-International Institute for Social and Economics Sciences. -

D. Main Contributors to Poverty Reduction Capacity, and Labor Market Outcomes Are High and Persistent

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Systematic Country Diagnostic Turkey’s Future Transitions Public Disclosure Authorized Towards Sustainable Poverty Reduction and Shared Prosperity Public Disclosure Authorized II III Turkey’s Future Transitions Towards Sustainable Poverty Reduction and Shared Prosperity Systematic Country Diagnostic October 12, 2016 IV V ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AFAD Prime Ministry Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency BEEPS Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey CEPEJ European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice CPI Consumer Price Index ECA Europe and Central Asia ECE Early Childhood Education EE Energy Efficiency EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMRA Energy Market Regulatory Authority EPIAS Energy Exchange EU European Union FDI Foreign Direct Investment GDP Gross Domestic Product GNI Gross National Income HBS Household Budget Survey IRA Independent Regulatory Agency LFP Labor Force Participation LFS Labor Force Survey LNG Liquefied Natural Gas LPI Logistics Performance Index NUTS2 Nomenclature of Territorial Units OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development PFMC Public Financial Management and Control PISA Program for International Student Assessment PMR Product Market Regulation PPL Public Procurement Law PPP Purchasing Power Parity R&D Research and Development Vice Presidents: Cyril Muller, Dimitris Tsitsiragos SCD Systematic Country Diagnostic IBRD Country Director: Johannes Zutt SILC Survey on Income and Living Conditions IFC Regional Director: -

Poverty Trends in Turkey IZA DP No

IZA DP No. 7823 Poverty Trends in Turkey Sirma Demir Șeker Stephen P. Jenkins December 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Poverty Trends in Turkey Sirma Demir Șeker Ministry of Development, Ankara Stephen P. Jenkins London School of Economics, University of Essex and IZA Discussion Paper No. 7823 December 2013 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

The Role of Zakat Potential in Reducing Poverty in Turkey Niyazi

International Journal of Islamic Economics and Finance Studies, 2019/2: 90-110 The Role of Zakat Potential in Reducing Poverty in Turkey Niyazi Gümüş * Fatih Yardımcıoğlu** Nurullah Altıntaş*** Received: 11.06.2019 Accepted: 27.07.2019 DOI: 10.25272/ijisef.575488 Type: Research Article Abstract Poverty has been the leading social and economic problem of societies both in the past and today for the decades. This study examines the status of poverty in the Turkish economy and the role of zakat in poverty reduction. The zakat potential is analyzed in three methods and it is concluded that poverty in Turkey could be completely resolved via a potential zakat fund. It is suggested that to reduce poverty in Turkey, zakat should be enforced by favor of the state and it should be based on institutional foundations. Keywords: Poverty, Reduction Poverty, Zakat, Zakat Potential Jel Codes: E62, I31, P24, Z12. * PhD Student, Sakarya University, Institute of Social Sciences, E-mail:[email protected]; This study is derived from the doctoral dissertation titled “A solution to poverty reduction: an example of a zakat fund”, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3928-6937 **Assoc. Professor, Sakarya University, Faculty of Political Sciences, Department of Public Finance, E- mail: [email protected], ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7758-8549 ***Assistant Professor, Sakarya University, Faculty of Political Sciences, Department of Economics, E- mail: [email protected], ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9425-3516 Uluslararası İslam Ekonomisi ve Finansı Araştırmaları Dergisi, 2019/2: 90-110 90 The Role of Zakat Potential in Reducing Poverty in Turkey Introduction Poverty has been the leading fundamental problem since the beginning of the history of humanity, and even today, societies try to overcome it. -

The Levy Institute Measure of Time and Consumption Poverty for Turkey

TIME DEFICITS AND POVERTY The Levy Institute Measure of Time and Consumption Poverty for Turkey Ajit Zacharias, Thomas Masterson, and Emel Memis¸ January 2014 1 Final Report Empowered lives. Resilient nations. 1 Draft: Please do not quote or cite without permission of the authors. Time Deficits and Poverty The Levy Institute Measure of Time and Consumption Poverty for Turkey Ajit Zacharias,Thomas Masterson, and Emel Memiş January 2014 Final Report* * Draft. Please do not quote or cite without permission of the authors. Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. iii List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... iv Preface ......................................................................................................................................................... vi Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................... vii 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 2 BACKGROUND AND LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................... 3 2.2 Trends in Employment, Income and Poverty ............................................................................... -

Society at a Glance 2014 Highlights: TURKEY OECD Social Indicators

(Under embargo until Tuesday 18th March - 11am Paris time) Society at a Glance 2014 Highlights: TURKEY OECD Social Indicators With 49.7% of employed adults, Turkey has the 2nd lowest employment rate in the OECD, slightly higher than Greece. In no other country is the employment rate for women lower (29.8%), despite an increase by 7 percentage points between 2007 and 2013. The Turks have the 2nd shortest life expectancy among the OECD countries at 74.6 years, after Mexico. Even so, in no other OECD country did life expectancy increase more from 1970 to 2011 (20.4 years). Income inequality and poverty in Turkey is high Disposable household income in Turkey is about 45% of the OECD average. Turkey also has the 3rd highest level of income inequality and the 3rd highest level of relative poverty in the OECD area. One in every five Turks is poor, compared with just above one in ten on average across the OECD. One out of three Turks report that they cannot afford to buy sufficient food, compared with an OECD average of less than one out of seven. Public social spending in Turkey at 12.8% of GDP is substantially lower than the OECD average of 21.8%. Most of the social spending is related to health, old age and survivors benefits, while support for the working-age population is very low. Relative poverty rates Percentage of adults living in Total fertility rate from 2000 to 2011 % of persons living with less workless households than 50% of median income 25% 2012 2007 Turkey Israel EU OECD 20% 20% 3.0 Hundreds 15% 15% 2.5 Replacement level of 2.1 10% 10% 2.0 5% 5% 1.5 0% 0% 1.0 2000 2005 2011 Turkey OECD EU Turkey OECD EU [Figure 5.3.xls] [Figure 1.5.xls] [Figures 3.3-3.4.xls] 1 Society at a Glance 2014 – OECD Social Indicators www.oecd.org/social/societyataglance.htm © OECD March 2014 The share of workless households has dropped The share of workless households at 15% is slightly above the OECD average. -

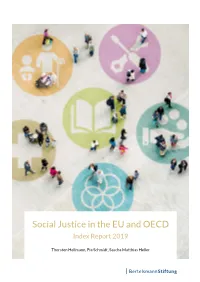

Social Justice in the EU and OECD Index Report 2019

Social Justice in the EU and OECD Index Report 2019 Thorsten Hellmann, Pia Schmidt, Sascha Matthias Heller EU and OECD Social Justice Index 2019 1 Iceland 7.90 2 Norway 7.68 3 Denmark 7.67 4 Finland 7.24 Norway Iceland Finland 5 Sweden 6.98 6 Netherlands 6.97 United Kingdom Sweden Estonia 7 Slovenia 6.88 Latvia 8 Czechia 6.80 Denmark 9 New Zealand 6.75 Lithuania Ireland 10 Germany 6.64 Netherlands Poland Germany 11 United Kingdom 6.64 Belgium Luxembourg Czechia 12 Canada 6.57 Slovakia Austria 13 Ireland 6.56 Switzerland Hungary Slovenia Romania 14 Switzerland 6.56 France Croatia 15 France 6.53 Bulgaria 16 Poland 6.42 Italy Portugal Spain 17 Austria 6.33 Canada Turkey 18 Belgium 6.31 Greece 19 Luxembourg 6.23 Malta Cyprus 20 Cyprus 6.10 Israel 21 Hungary 6.09 EU/OECD Average 6.09 United States 22 Slovakia 6.07 23 Malta 6.07 24 Portugal 6.03 Mexico 25 Estonia 5.98 26 Australia 5.91 Korea Japan 27 Japan 5.62 28 Spain 5.53 29 Italy 5.48 30 Israel 5.48 31 Lithuania 5.36 32 Croatia 5.29 33 Latvia 5.21 34 Korea 5.18 35 Greece 5.10 36 United States 5.05 37 Chile 4.92 38 Bulgaria 4.91 39 Romania 4.86 Australia 40 Turkey 4.86 41 Mexico 4.76 Chile New Zealand Source: Social Justice Index. EU and OECD Social Justice Index 2019 1 Iceland 7.90 2 Norway 7.68 3 Denmark 7.67 4 Finland 7.24 Norway Iceland Finland 5 Sweden 6.98 6 Netherlands 6.97 United Kingdom Sweden Estonia 7 Slovenia 6.88 Latvia 8 Czechia 6.80 Denmark 9 New Zealand 6.75 Lithuania Ireland 10 Germany 6.64 Netherlands Poland Germany 11 United Kingdom 6.64 Belgium Luxembourg Czechia 12 Canada -

Poverty and Social Exclusion in the Slum Areas of Large Cities in Turkey

POVERTY AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN THE SLUM AREAS OF LARGE CITIES IN TURKEY Fikret Adaman (Economics Department, Boğaziçi University) Çağlar Keyder (Sociology Department, Boğaziçi University) with the contributions of Serra Müderrisoğlu (Psychology Department, Boğaziçi University) Bediz Yılmaz (Public Administration Department, Mersin University) Deniz Yükseker (Sociology Department, Koç University) The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the positions of the European Commission as well as the Ministry of Labour and Social Security of Turkey. INDEX. Acknowledgement …………………………………………………………………………………..…ii Executive summary …………………………………………………………………………………… iv INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………..1 Chapter 1: POVERTY AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION: A THEORETICAL OUTLINE………4 Chapter 2: POVERTY AND SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN TURKEY: A TOUR d’HORIZON General Picture…..……………………………………………………………………………15 Far Away, So Close: Social Exclusion and Spatial Relegation in an Inner-City Slum of İstanbul (by Bediz Yılmaz)…………………………………………………………………...26 Severed from Their Homeland and Livelihoods: The Internal Displacement of Kurds in Turkey as a Process of Social Exclusion (by Deniz Yükseker)………………………………41 To Work or Not to Work: That Is the Question! (by Serra Müderrisoğlu)………..………….56 Chapter 3: RESEARCH RESULTS AND ANALYSIS……………………………………...68 Chapter 4: CONCLUDING REMARKS AND POLICY SUGGESTIONS…………….…..128 REFERENCES………………………………………………………………………………145 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report on social exclusion in the slum areas of big cities in Turkey has been prepared for the European Commission, Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities DG (with grant no. VC/2005/0155), with the aim of serving the “Joint Inclusion Memorandum (JIM)” process. The matching fund was provided by the Research Foundation of Boğaziçi University (with grant no. 06M101). The authors are grateful to both institutions for the financial support they have provided. -

The CASE STUDY on Income and Social Inequalities in Turkey Inequalities in Turkey: an Overview

The CASE STUDY on Income and Social Inequalities in Turkey Inequalities in Turkey: An Overview Final report Ayşe Buğra and Volkan Yılmaz, with Alpkan Birelma, Burçak Gürsoy, Yasemin Taşkın, Zeynep Berra Dodurka, Başak Ekim Akkan, İpek Göçmen. Boğaziçi University Social Policy Forum I. Introduction Equality has been one of the most popular and inspirational promises of modern citizenship.1 In social policy, following the footsteps of T. H. Marshall, citizenship status has been widely discussed in its potential to act against social inequalities especially through redistributive and transformative social policies.2 More recently, after a period when inequalities have at times been portrayed as an incentive for economic and human development, different dimensions of inequality are, once again, becoming part of global and domestic policy debates as roots or manifestations of social problems. Inclusion of measures of inequalities, namely Inequality- Adjusted Human Development Index and Gender Inequality Index, into the human development paradigm symbolised an important development in this direction. Increasing number of studies now show the harmful impact of inequality on health and wellbeing of societies.3 Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett’s inspiring study –The Spirit Level: Why Equality is Better for Everyone- clearly demonstrated that the more egalitarian societies, the better they perform in various domains such as mental health, physical health, 1 Amartya Sen elaborates this promise of equality by pursuing the questions of why equality matters and equality of what matters. See, Amartya Sen, Inequality Re-examined (New York: Harvard and Russell Sage Foundation, 1995). 2 T. H. Marshall, “Citizenship and Social Class,” In Welfare States: Construction, Deconstruction, Reconstruction Volume I, eds. -

UNDP in Turkey

Country Fact Sheets Turkey The Human Development Index – going beyond income The human development index (HDI) focuses on three measurable dimensions of human development: living a long and healthy life, being educated and having a decent standard of living. Thus it combines measures of life expectancy, school enrolment, literacy and income to allow a broader view of a country’s development than does income alone. Although the HDI is a useful starting point, it is important to remember that the concept of human development is much broader and more complex than any summary measure can capture, even when supplemented by other indices. The HDI is not a comprehensive measure. It does not include important aspects of human development, notably the ability to participate in the decisions that affect one’s life and to enjoy the respect of others in the community. It is also important to note that the HDI is constructed using data from international sources. Sometimes more up-to-date data are available nationally, and sometimes there are slight differences in definitions between international and national data. For these and other reasons, discrepancies with national sources may occur. HDI GDP per GDP per GDP per HDI rank capita capita capita value 2003 rank (PPP value 2003 (177 2003 US$) (PPP US$) countries) (177 rank 2003 countries) minus HDI rank (higher means better on HDI) Turkey 94 76 -18 6,772 0.750 Southern Europe Countries Best performer in Southern Europe 29 31 2 18,776 0.891 (Cyprus) Worst performer in Southern Europe 94 76 -18 6,772 0.750 (Turkey) Turkey is ranked 94th in the 2005 Human Development Report, with an HDI value of 0.750.