Social Justice in the EU and OECD Index Report 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Justice in an Open World – the Role Of

E c o n o m i c & Social Affairs The International Forum for Social Development Social Justice in an Open World The Role of the United Nations Sales No. E.06.IV.2 ISBN 92-1-130249-5 05-62917—January 2006—2,000 United Nations ST/ESA/305 DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS Division for Social Policy and Development The International Forum for Social Development Social Justice in an Open World The Role of the United Nations asdf United Nations New York, 2006 DESA The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint course of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises inter- ested Governments on the ways and means of translating policy frameworks devel- oped in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. Note The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations. The designations employed and the presentation of the mate- rial do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitations of its frontiers. -

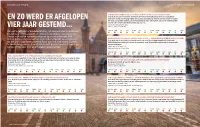

En Zo Werd Er De Afgelopen Vier Jaar Gestemd

UITKERINGSGERECHTIGDEN TWEEDE KAMER VERKIEZINGEN EEN INKOMENSAANVULLING VOOR MENSEN MET EEN MEDISCHE URENBEPERKING Deze motie beoogde te bereiken dat mensen met een beperking/handicap die naar hun maximale EN ZO WERD ER AFGELOPEN vermogen werken, een toeslag krijgen die los staat van eventueel inkomen van een partner of ouders. Dit omdat zij vanwege die medische urenbeperking dus maar een beperkt aantal uren kunnen werken en zodoende onvoldoende inkomen kunnen genereren. Stemdatum: 24 september 2019 VIER JAAR GESTEMD… Indiener: Jasper van Dijk (SP) Van extra geld voor armoedebestrijding, tot aanpassingen in de Wajong. 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD De afgelopen vier jaar heeft de Tweede Kamer kunnen stemmen over diverse voorstellen ter verbetering van de sociale zekerheid. FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden heeft er acht moties uitgepikt. Groen betekent AANPASSEN WETSVOORSTEL WAJONG OM DE REGELS TE HARMONISEREN ZONDER VERSLECHTERING Deze motie was bedoeld om het alternatief zoals opgesteld door belangenorganisaties (onder wie dat een partij voor heeft gestemd. Rood was een stem tegen. Duidelijk FNV Uitkeringsgerechtigden) in de wet te verwerken, zodat de nadelige gevolgen van de harmonisatie te zien is dat geen van de moties het heeft gehaald omdat de regerings- worden voorkomen. partijen (VVD, CDA, D66 en CU) steeds tegenstemden. Stemdatum: 30 oktober 2019 Indieners: PvdA, GL, SP en 50Plus 50PLUS CDA CU D66 DENK FvD GL PvdA PvdD PVV SGP SP VVD EEN AANGESCHERPT AFSLUITINGSBELEID VOOR DRINKWATER EN WIFI Deze motie was opgesteld om naast gas en elektriciteit ook drinkwater en internet op te nemen als basis- voorziening. Dit om te voorkomen dat mensen met een betalingsachterstand in een onleefbare situatie EXTRA GELD OM DE GEVOLGEN VAN ARMOEDE ONDER KINDEREN TE BESTRIJDEN belanden als deze voorzieningen worden afgesloten. -

I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 Maart 2021

Rapport I&O-Zetelpeiling 15 maart 2021 VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans Colofon Maart peiling #2 I&O Research Uitgave I&O Research Piet Heinkade 55 1019 GM Amsterdam Rapportnummer 2021/69 Datum maart 2021 Auteurs Peter Kanne Milan Driessen Het overnemen uit deze publicatie is toegestaan, mits de bron (I&O Research) duidelijk wordt vermeld. 15 maart 2021 2 van 15 Inhoudsopgave Belangrijkste uitkomsten _____________________________________________________________________ 4 1 I&O-zetelpeiling: VVD levert verder in ________________________________________________ 7 VVD levert verder in, D66 stijgt door _______________________ 7 Wie verliest aan wie en waarom? _________________________ 9 Aandeel zwevende kiezers _____________________________ 11 Partij van tweede (of derde) voorkeur_______________________ 12 Stemgedrag 2021 vs. stemgedrag 2017 ______________________ 13 2 Onderzoeksverantwoording _________________________________________________________ 14 15 maart 2021 3 van 15 Belangrijkste uitkomsten VVD levert verder in; D66 stijgt door; Volt en Ja21 maken goede kans In de meest recente I&O-zetelpeiling – die liep van vrijdag 12 tot maandagochtend 15 maart – zien we de VVD verder inleveren (van 36 naar 33 zetels) en D66 verder stijgen (van 16 naar 19 zetels). Bij peilingen (steekproefonderzoek) moet rekening gehouden worden met onnauwkeurigheids- marges. Voor VVD (21,0%, marge 1,6%) en D66 (11,8%, marge 1,3%) zijn dat (ruim) 2 zetels. De verschuiving voor D66 is statistisch significant, die voor VVD en PvdA zijn dat nipt. Als we naar deze zetelpeiling kijken – 2 dagen voor de verkiezingen – valt op hoezeer hij lijkt op de uitslag van de Tweede Kamerverkiezingen van 2017. Van de winst die de VVD boekte in de coronacrisis is niets over: nu 33 zetels, vier jaar geleden ook 33 zetels. -

COULD POVERTY BE TURNED INTO PROSPERITY and POOR INTO RICH in TURKEY’S REALITY? Asst

Niğde Üniversitesi, İ.İ.B.F. Dergisi, 2010, Cilt:3, Sayı:2, s.135-161. 135 COULD POVERTY BE TURNED INTO PROSPERITY and POOR INTO RICH IN TURKEY’S REALITY? Asst. Assoc. Dr. Haldun SOYDAL1 Asst. Assoc. Dr. Serkan GÜZEL2 Res. Assist. M. Göktuğ KAYA3 ABSTRACT Arguments not only over the poverty of individuals but also over the poverty of groups, communities, nations, and countries have begun to make several kind of poverties, including individualistic, economical, regional, cultural, the main point of the escalating studies. In this sense, the main aim of this paper representing a significant indicator for studies mentioned above is determining the concept of poor and poverty, unveiling underlying factors of poverty and putting forth how to cope with poverty. One the the most crucial result of this paper highlighting the role of Turkey‟s policy that make inequality of income distribution, black economy and irregularity legislative is closely linked with the political conciousness that will be able to turn poverty into prosperity in general and poor into rich in particular in the reality of Turkey, via distributing internal revenue as regards contribution of individuals, groups, social classes and via improving national capital. Keywords: Poverty, Poor, Poverty Line, Struggle Against Poverty. JEL Codes: I38, A14, H11 ÖZET Sadece bireylerin değil aynı zamanda grup, topluluk, ulus ve ülkelerin yoksulluğu üzerine tartıĢmalar, bireysel, ekonomik, bölgesel, kültürel pek çok yoksulluk çeĢidini giderek artan çalıĢmaların temel hareket noktası haline getirmeye baĢlamıĢtır. Bu anlamda sözü edilen çalıĢmalara anlamlı bir gösterge oluĢturan bu çalıĢmanın temel amacı, yoksul ve yoksulluk kavramlarını saptamak, yoksulluğun nedenlerini açığa çıkarmak ve yoksulluğun üstesinden nasıl gelineceğini öne sürmektir. -

The Dairy Milk Sector in Lower Saxony and Germany

The Dairy Milk Sector in Lower Saxony and Germany Compiled by Max Lesemann, IHK Hannover October 2020 Inhalt List of figures and tables ................................................................................. Index of abbreviations .................................................................................... I. Introduction .......................................................................................... 5 II. Market ................................................................................................. 6 I. Company Structures and Federations ..................................................... 6 II. Production ...................................................................................... 8 III. International Trade ......................................................................... 12 IV. Consumption ................................................................................. 15 III. Digitalization, Industry 4.0 and Internet of Things in the milk industry .......... 20 IV. Sustainability ................................................................................... 22 V. Innovations and Trends ...................................................................... 29 VI. Prospect ......................................................................................... 31 VII. Bibliography ..................................................................................... 34 List of figures and tables Figure 1: The amount of different milk products per year from 2014 to 2018 -

A Sketch of Politically Liberal Principles of Social Justice in Higher Education

Phil Smith Lecture A SKETCH OF POLITICALLY LIBERAL PRINCIPLES OF SOCIAL JUSTICE IN HIGHER EDUCATION Barry L. Bull Indiana University John Rawls was probably the world’s most influential political philosopher during the last half of the 20th century. In 1971, he published A Theory of Justice,1 in which he attempted to revitalize the tradition of social contract theory that was first used by Thomas Hobbes and John Locke in the 17th century. The basic idea of this tradition was that the only legitimate form of government was one to which all citizens had good reason to consent, and Locke argued that the social contract would necessarily provide protections for basic personal and political liberties of citizens. In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson charged that the English King George III had violated these liberties of the American colonists, and therefore the colonies were justified in revolting against English rule. Moreover, the Bill of Rights of the Constitution of the United States can be understood as protecting certain basic liberties—freedom of religion and expression, for example—on the grounds that they are elements of the social contract that place legitimate constraints on the power of any justifiable government. During the late 18th and 19th centuries, however, the social contract approach became the object of serious philosophical criticism, especially because the existence of an original agreement among all citizens was historically implausible and because such an agreement failed to acknowledge the fundamentally social, rather than individual, nature of human decision making, especially about political affairs. In light of this criticism, British philosophers, in particular Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, suggested that the legitimate justification of government lay not with whether citizens actually consented to it but with whether it and its policies were designed to maximize the happiness of its citizens and actually had that effect. -

A Day in Luxembourg, LUXEMBOURG

A Day in Luxembourg, LUXEMBOURG Why you should visit Luxembourg Luxembourg is the epitome of “the charming European city” we all grew up imagining. It’s amazingly cosmopolitan but not overwhelming, except for its extremely complex history. Its gorges traverse the city, making it a spectacular three-dimensional city, with lit-up fortifications along the walls of the gorges -- perfect for the historian and the romantic. And the food is a lovely mix of French, German, Italian and of course Luxembourgish. Three things you might be surprised to learn about Luxembourg and the people 1. Luxembourg is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site due to its old quarters and fortifications. 2. General George Patton is buried here 3. Villeroy & Boch ceramics started in Luxembourg Favorite Walks/areas of town Go to the visitors center in Place Guillaume to sign up for any of the many fantastic—and reasonably priced—group or individual walking, biking or driving (even in your own car) historic tours with an official guide. The tours can include visits to: • Historic city center • The Petrusse gorge next to the city center • The historic Grund, down below the city center • Clausen, near the Grund • Petrusse and Bock Casemates Other very good things to do/see • American Military Cemetery, Hamm: A beautiful cemetery with more than 5,000 soldiers, most of whom fell in the Battle of the Bulge of WWII in 1944-45. The cemetery also has an impressive chapel and is the burial place of General George Patton. www.abmc.gov/cemeteries/cemeteries/lx.php • German Military Cemetery, Sandweiler: A short drive from the Hamm cemetery, this cemetery has a much more somber feel to it, containing more than 10,000 German soldiers who perished in the Battle of the Bulge in 1944-45. -

ROMA and LUXEMBOURGERS There Are People Who Love And

ROMA AND LUXEMBOURGERS There are people who love and people who hate Europe. I happen to be a fan. The European Union ended wars, queuing up for the customs and it gave a voice to even the smallest member-states, like Luxemburg with 500.000 residents. Yet millions of other EU citizens have no say in the matter, no Commissioner of their own and no MEPs in Brussels, for the mere reason that they are an ethnic minority, like Roma and Sinti, Europe's largest minority. Why double standards? Is it because Luxembourgers are all white and Roma all dark? They are not. Thousand years ago, Roma left India and went to Russia, Persia, Turkey and Europe. Some intermarried with Jews and other non-Roma, or they lost their tan in Scandinavian countries. Even the Nazis noticed that racial purity is a difficult thing. They decided that 12.5 % of Roma or Jewish blood was enough to be deported. Gadje, non-Roma, also have mixed blood. New archeological findings reveal that only 10 up to 20 % of Europeans descend from the original tribes, the others have DNA from the Middle East or Asia. The major difference between Luxembourgers and Roma does not stem from ethnicity but from something that used to be very important in Europe: borders. Luxembourgers have them, Roma don't. The political relevance of the term "ethnic minority" is rather dubious. It means counting people in, not seldom to count them out. The reunification of Europe has deprived a whole nation from fundamental rights and this mainly happened because the 12 million Roma, present in larger numbers than Belgians, Swedes, Finns, Bulgarians, Czechs, Greeks, Danish, or Luxembourgers, did not live together in their own nation-state. -

Older People in Germany and the EU 2016

OLDER PEOPLE in Germany and the EU Federal Statistical Office of Germany Published by Photo credits Federal Statistical Office, Wiesbaden Cover image Title © Monkey Business Images / Editing Shutterstock.com Thomas Haustein, Johanna Mischke, Frederike Schönfeld, Ilka Willand Page 9 © iStockphoto.com / vitranc Page 53 © iStockphoto.com / XiXinXing Page 16 © Image Source / Topaz / F1online Page 60 © Peter Atkins - Fotolia.com English version edited by Michaela Raimer, Page 17 © iStockphoto.com / Squaredpixels Page 67 © iStockphoto.com / Kristina Theis Page 27 © Westend61 - Fotolia.com monkeybusinessimages Page 29 © bluedesign - Fotolia.com Page 71 © iStockphoto.com / PeopleImages Design and layout Page 31 © iStockphoto.com / Xavier Arnau Page 73 © runzelkorn - Fotolia.com Federal Statistical Office Page 36 © iStockphoto.com / mheim3011 Page 75 © iStockphoto.com / Published in October 2016 Page 37 © iStockphoto.com / miriam-doerr Christopher Badzioch Page 39 © Lise_Noergel / photocase.de Page 77 © iStockphoto.com / funstock Order number: 0010021-16900-1 Page 40 © iStockphoto.com / budgaugh Page 80 © iconimage - Fotolia.com Page 45 © Statistisches Bundesamt Page 89 © iStockphoto.com / vm Page 46 © iStockphoto.com / Attila Barabas Page 90 © frau.L. / photocase.de Page 49 © iStockphoto.com / Gizelka Page 93 © fusho1d - Fotolia.com Page 49 © iStockphoto.com / Vladyslav Danilin Page 51 © iStockphoto.com / pamspix This brochure was published with the financial support of the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth. -

Luxembourg Resistance to the German Occupation of the Second World War, 1940-1945

LUXEMBOURG RESISTANCE TO THE GERMAN OCCUPATION OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR, 1940-1945 by Maureen Hubbart A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Major Subject: History West Texas A&M University Canyon, TX December 2015 ABSTRACT The history of Luxembourg’s resistance against the German occupation of World War II has rarely been addressed in English-language scholarship. Perhaps because of the country’s small size, it is often overlooked in accounts of Western European History. However, Luxembourgers experienced the German occupation in a unique manner, in large part because the Germans considered Luxembourgers to be ethnically and culturally German. The Germans sought to completely Germanize and Nazify the Luxembourg population, giving Luxembourgers many opportunities to resist their oppressors. A study of French, German, and Luxembourgian sources about this topic reveals a people that resisted in active and passive, private and public ways. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Clark for her guidance in helping me write my thesis and for sharing my passion about the topic of underground resistance. My gratitude also goes to Dr. Brasington for all of his encouragement and his suggestions to improve my writing process. My thanks to the entire faculty in the History Department for their support and encouragement. This thesis is dedicated to my family: Pete and Linda Hubbart who played with and took care of my children for countless hours so that I could finish my degree; my husband who encouraged me and always had a joke ready to help me relax; and my parents and those members of my family living in Europe, whose history kindled my interest in the Luxembourgian resistance. -

Daimler Annual Report 2014

Annual Report 2014. Key Figures. Daimler Group 2014 2013 2012 14/13 Amounts in millions of euros % change Revenue 129,872 117,982 114,297 +10 1 Western Europe 43,722 41,123 39,377 +6 thereof Germany 20,449 20,227 19,722 +1 NAFTA 38,025 32,925 31,914 +15 thereof United States 33,310 28,597 27,233 +16 Asia 29,446 24,481 25,126 +20 thereof China 13,294 10,705 10,782 +24 Other markets 18,679 19,453 17,880 -4 Investment in property, plant and equipment 4,844 4,975 4,827 -3 Research and development expenditure 2 5,680 5,489 5,644 +3 thereof capitalized 1,148 1,284 1,465 -11 Free cash flow of the industrial business 5,479 4,842 1,452 +13 EBIT 3 10,752 10,815 8,820 -1 Value added 3 4,416 5,921 4,300 -25 Net profit 3 7,290 8,720 6,830 -16 Earnings per share (in €) 3 6.51 6.40 6.02 +2 Total dividend 2,621 2,407 2,349 +9 Dividend per share (in €) 2.45 2.25 2.20 +9 Employees (December 31) 279,972 274,616 275,087 +2 1 Adjusted for the effects of currency translation, revenue increased by 12%. 2 For the year 2013, the figures have been adjusted due to reclassifications within functional costs. 3 For the year 2012, the figures have been adjusted, primarily for effects arising from application of the amended version of IAS 19. Cover photo: Mercedes-Benz Future Truck 2025. -

Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in Forest

Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in the Forest Communities of Turkey Evidence and policy impact analysis POVERTY, FOREST DEPENDENCE AND MIGRATION IN THE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF TURKEY A B POVERTY, FOREST DEPENDENCE AND MIGRATION IN THE FOREST COMMUNITIES OF TURKEY Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in the Forest Communities of Turkey Evidence and policy impact analysis JUNE, 2017 Acknowledgements This paper was prepared by a combined team1 of World Bank staff and consultants, working with local Turkish consultants and stakeholders in close collaboration.2 The team would like to acknowledge the efforts of UDA Consulting in Turkey for the survey’s design and implementation. The team would like to acknowledge the support and design contributions of the Program for Forests (PROFOR), who also funded this study. Additionally, the team would like to acknowledge the cooperation of the General Directorate of Forestry (GDF), who provided guidance and the oversight of information that led to the construction of the survey and sample design. The findings from this paper form an integral part of a much broader engagement with the Turkish GDF through a jointly-produced Forest Policy Note. 1 The Team comprised: Craig M. Meisner (World Bank, Task Team Leader and Sr Environmental Economist), Limin Wang (World Bank, Consultant), Raisa Chandrashekhar Behal (World Bank, Consultant), and Priya Shyamsundar (World Bank, Consultant), Andrew Mitchell (World Bank, Sr Forestry Specialist), and Esra Arikan (World Bank, Sr Environmental Specialist). 2 Local Turkish collaborators included: UDA Consulting for survey implementation and the Central Union of Turkish Forestry Cooperatives (OR-KOOP). CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................