Conservation of Botanical and Wildlife Values of Ngamatea Swamp, Waiouru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classifications

Classifications rt.code.desc Classifications Code Classifications rt.code.base Akitio River Scheme - River Maintenance RC Direct Benefit AREA Akitio River Scheme - Contributor CN Contributor AREA Ashhurst Scheme - Flood Protection AC Flooding Urban CAPITAL Ashhurst Scheme - Flood Protection SUIP AN Annual Charge TARGET Ashhurst Scheme - Lower Stream Maintenance AL Channel Maintenance High AREA Ashhurst Scheme - Upper Stream Maintenance AU Channel Maintenance Low AREA Eastern Manawatu - Lower River Maintenance EL Channell Maintenane High AREA Eastern Manawatu - Upper River Maintenance EU Channell Maintenance low AREA Eastern Manawatu River Scheme - Contributor CN Contributor AREA Eastern Manawatu River Scheme - Indirect IN Indirect Benefit TARGET Forest Road Drainage Scheme A High Benefit AREA Forest Road Drainage Scheme B Medium Benefit AREA Forest Road Drainage Scheme C Moderate Benefit AREA Forest Road Drainage Scheme D Low Benefit AREA Forest Road Drainage Scheme E Minor Benefit AREA Forest Road Drainage Scheme F Indirect Benefit AREA Foxton East Drainage Scheme D1 High Benefit AREA Foxton East Drainage Scheme D2 Medium Benefit AREA Foxton East Drainage Scheme D3 Moderate Benefit AREA Foxton East Drainage Scheme D4 Minor Benefit AREA Foxton East Drainage Scheme D5 Low Benefit AREA Foxton East Drainage Scheme SUIP AC Annual Charge TARGET Foxton East Drainage Scheme Urban U1 Urban CAPITAL Haunui Drainage Scheme A Direct Benefit CAPITAL Himatangi Drainage Scheme A High Benefit AREA Himatangi Drainage Scheme B Medium Benefit AREA Himatangi -

THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 51

1334 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE No. 51 Declaring Land in Roadways Laid Out in Block IX, Kerikeri hereto is hereby taken for a rubbish tip and shall vest in Survey District, Bay of Islands County, to be Road the Chairman, Councillors, and Inhabitants of the County of Taumarunui as from the date hereinafter mentioned; and I also declare that this Proclamation shall take effect 0]1 DENIS BLUNDELL, Governor-General and after the 19th day of June 1975. A PROCLAMATION PURSUANT to section 421 of the Maori Affairs Act 1953, SCHEDULE I, Sir Edward Denis Blundell, the Governor-General of New WELLINGTON LAND DISTRICT Zealand, hereby declare the land described in the Schedule ALL that piece of land containing 1.2410 hectares situated hereto, and comprised in roadways laid out by the Maori in Block II, Puketi Survey District, being part Pukawa 4Bl; Land Court by an order dated the 24th day of August as shown marked A on plan S.O. 30343 lodged in the office 1970 to be road, and to be vested in the Chairman, Council of the Chief Surveyor at Wellington. lors, and Inhabitants of the County of Bay of Islands. Given under the hand of His Excellency the Governor General, and issued under the Seal of New Zealand, SCHEDULE this 28th day of May '1975. NORTII AUCKLAND LAND DISTRICT [L.s.] M. A. CONNELLY, Minister of Works and Development. ALL those pieces of land situated in Block IX, Kerikeri Survey District, described as follows: Goo SAVE TIIB QUEEN! A. R. P. Being (P.W. 53/323/1; Wg. -

Great Walks Track Guide Tongariro 2019-20

W h a k a " p a p a T R i o v e N r a t io n a l P W h a a r W k k a p a a p a i i k t i S a t r e r a e m S H t W r e o a l m h i d a a k y a 4 p 8 P a a p r k a R " S " a i l p i c i d a s " E W a i r " e " r e " S 4 7 t " r R e a o m M a d a Mangat e epopo Str n eam n g d a " S t P e u E h k p T F e e a o a o T n l r o l # l t a a p s T # u e n k ra e o a n r g k i i " " W M ha nganui River a a N n n " g d # a # T C S a C a " o t t d n o e d e a i l p e o m n " o n p g p s ( o a a N i # t # P g l L H r T e 1 u ā o a 6 T k i u P w 9 m e a P 2 r k e t m a m a u a r o i k n a i o r a r l e a E k S S a k " o p e T d r R i U s a T a n a m p g o R m p s I H G a a e a o H K N ) r d T t O e # S O e # t N M P # e F 2 p U # g T M o n t 2 A B r o a a # 1 " u o i 8 C # L n T u 9 n d h n u 7 I K C a 1 g r 6 C t g i n u m m 6 E a 7 s t h S 2 S r e m a i o 3 S r o e h t m e e t l C R a t " " r e " e h a d t r i e W r " " a a a n E ( i N n h m d g O d # o " e ā # R C r B ( o t h a R o T C u l l t t e a u d o o o e " r e a p t m W # " L o n e a R # L m a p u a a u r T 1 a n k o p e i n 7 e g k e u p W 3 g S L " a s M e H s n 9 a i u s H h a a i h m g u t l a ī m a i p r o e u r t o k h t i u o e a a u t ) n a ) r t " a W a i h o h " o n u S t r e a m M a n g 4 a 7 h R o O u o L " h t t a u o o r u k e a n r e e u i r i S a S t r t e r e a a M m a m n g W S S a a S T t i H H u t o o 1 r 4 r e e u a t 7 r a o t n a m e u o g n t i u o i 1 W well-managed, renewable and legally logged forests. -

Council Agenda Extraordinary Meeting

MASTERTON DISTRICT COUNCIL COUNCIL AGENDA EXTRAORDINARY MEETING MONDAY 30 AUGUST 2021 4.30PM MEMBERSHIP Her Worship (Chairperson) Cr G Caffell Cr B Gare Cr D Holmes Cr B Johnson Cr G McClymont Cr F Mailman Cr T Nelson Cr T Nixon Cr C Peterson Cr S Ryan Noce is given that an extraordinary meeng of the Masterton District Council will be held at 4.30pm on Monday 30 August 2021 . RECOMMENDATIONS IN REPORTS ARE NOT TO BE CONSTRUED AS COUNCIL POLICY UNTIL ADOPTED 26 August 2021 Values 1. Public interest: members will serve the best interests of the people within the Masterton district and discharge their duties conscientiously, to the best of their ability. 2. Public trust: members, in order to foster community confidence and trust in their Council, will work together constructively and uphold the values of honesty, integrity, accountability and transparency. 3. Ethical behaviour: members will not place themselves in situations where their honesty and integrity may be questioned, will not behave improperly and will avoid the appearance of any such behaviour. 4. Objectivity: members will make decisions on merit; including appointments, awarding contracts, and recommending individuals for rewards or benefits. 5. Respect for others: will treat people, including other members, with respect and courtesy, regardless of their ethnicity, age, religion, gender, sexual orientation, or disability. Members will respect the impartiality and integrity of Council staff. 6. Duty to uphold the law: members will comply with all legislative requirements applying to their role, abide by this Code, and act in accordance with the trust placed in them by the public. -

Notes Subscription Agreement)

Amendment and Restatement Deed (Notes Subscription Agreement) PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited Issuer The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 Subscribers 3815658 v5 DEED dated 2020 PARTIES New Zealand Local Government Funding Agency Limited ("Issuer") The Local Authorities listed in Schedule 1 ("Subscribers" and each a "Subscriber") INTRODUCTION The parties wish to amend and restate the Notes Subscription Agreement as set out in this deed. COVENANTS 1. INTERPRETATION 1.1 Definitions: In this deed: "Notes Subscription Agreement" means the notes subscription agreement dated 7 December 2011 (as amended and restated on 4 June 2015) between the Issuer and the Subscribers. "Effective Date" means the date notified by the Issuer as the Effective Date in accordance with clause 2.1. 1.2 Notes Subscription Agreement definitions: Words and expressions defined in the Notes Subscription Agreement (as amended by this deed) have, except to the extent the context requires otherwise, the same meaning in this deed. 1.3 Miscellaneous: (a) Headings are inserted for convenience only and do not affect interpretation of this deed. (b) References to a person include that person's successors, permitted assigns, executors and administrators (as applicable). (c) Unless the context otherwise requires, the singular includes the plural and vice versa and words denoting individuals include other persons and vice versa. (d) A reference to any legislation includes any statutory regulations, rules, orders or instruments made or issued pursuant to that legislation and any amendment to, re- enactment of, or replacement of, that legislation. (e) A reference to any document includes reference to that document as amended, modified, novated, supplemented, varied or replaced from time to time. -

HRE05002-038.Pdf(PDF, 152

Appendix S: Parties Notified List of tables Table S1: Government departments and Crown agencies notified ........................... 837 Table S2: Interested parties notified .......................................................................... 840 Table S3: Interested Māori parties ............................................................................ 847 Table S1: Government departments and Crown agencies notified Job Title Organisation City Manager Biosecurity Greater Wellington - The Regional Council Masterton 5915 Environment Health Officer Wairoa District Council Wairoa 4192 Ministry of Research, Science & Wellington 6015 Technology (MoRST) Manager, Animal Containment AgResearch Limited Hamilton 2001 Facility Group Manager, Legal AgResearch Limited Hamilton Policy Analyst Human Rights Commission Auckland 1036 Management, Monitoring & Ministry of Pacific Island Affairs Wellington 6015 Governance Fish & Game Council of New Zealand Wellington 6032 Engineer Land Transport Safety Authority Wellington 6015 Senior Fisheries Officer Fish & Game Eastern Region Rotorua 3220 Adviser Ministry of Research, Science & Wellington 6015 Technology (MoRST) Programme Manager Environment Waikato Hamilton 2032 Biosecurity Manager Environment Southland Invercargill 9520 Dean of Science and University of Waikato Hamilton 3240 Technology Director National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Wellington 6041 Research Limited (NIWA) Chief Executive Officer Horticulture and Food Research Institute Auckland 1020 (HortResearch Auckland) Team Leader Regulatory -

Target Taupo

TARGET TAUPO A newsletter for Hunters and Anglers in the Tongariro/Taupo Conservancy NOVEMBER 1996, ISSUE 23 Department of Conservation Te Papa Atawhai (t) The Caxton Press =I= (Foremost Printers & Publishers, Est. 1935) are privileged to announce the Publication in December 1996 of LIMITED EDITION of 750 hand numbered copies worldwide. 340 x 245mm, 144pp, casebound, gold blocked, headbands, ribbon and slipcase. Full colour printing of over 750 flies and lures displayed in over 50 plates - these are reproductions of the author's original displayed collection. Robert Bragg is the greatest name in the tying of New Zealand fishing flies. This superbly produced volume embodies a lifetime's experience and knowledge. It describes changes in fly dressing and fishing the lure, since the creation of the 'Canterbury Lures' around 1890. Other chaptersare devoted to the nymph dry fly fishingand tying imitationsin the angler's never-ending challenge to 'match the hatch'. "New Zealand Fishing Flies" will be invaluable for fishermenseeking to combat the growing elusiveness of trout and salmon in New Zealand with a greater awareness of what the author calls 'streamside entomology'. For the serious angler "New Zealand Fishing Flies" is an essential resource. Rarely is any traditional craft treated so meticulously in print and plate by such a master. To celebrate this unique publishing event we are providing FREEwith every book purchased, a set of 4 limited edition prints, numbered and in full colour by New Zealand Artist Michael Scheele who has become -

Environmental Impacts, Resource Management and Wahi Tapu and Portable Taonga

Taihape Inquiry District: Environmental Impacts, Resource Management and Wahi Tapu and Portable Taonga A Report Commissioned by the Crown Forestry Rentals Trust for the Waitangi Tribunal’s Taihape District Inquiry Professor Michael Belgrave David Belgrave Dr Chris Anderson Dr Jonathan Procter Erana Hokopaura Watkins Dr Grant Young Sharon Togher December, 2012 1 2 Table of Contents THE TAIHAPE ENVIRONMENTAL SCOPING REPORT ............................................................ 8 Method ........................................................................................................................................................ 12 PERSONNEL .................................................................................................................... 15 PROJECT TEAM ..................................................................................................................................................... 15 THE CLAIMS .................................................................................................................... 18 ECONOMIC ....................................................................................................................................................... 20 HEALTH AND SPIRITUAL .......................................................................................................................................... 21 POLITICAL ........................................................................................................................................................... -

No 6, 9 February 1967

No.6 143 THE NEW ZEALAND GAZETTE Published by Authority WELLINGTON: THURSDAY, 9 FEBRUARY 1967 Land Taken for the Construction of Public Offices in the City SCHEDULE of Auckland SOUlH AUCKLAND LAND DISTRICT ALL those pieces of land described as follows: BERNARD FERGUSSON, Governor-General A. R.. P. Being A PROCLAMATION o 0 34.4 Part Maungatapu 1K 2A Block; coloured blue on PURSUANT to the Public Works Act 1928, I, Brigadier Sir plan. Bernard Edward Fergusson, the Governor-General of New o 3 20.2 Part Maungatapu B Block; coloured yellow on Zealand, hereby proclaim and declare that the land described plan. in the First Schedule hereto, excepting thereout so much of the Situated in Block XV, Tauranga Survey District. airspace and subsO'il as is described in the Second Schedule hereto, is hereby taken for the construction of public offices, A. R. P. Being and shall vest in the Auckland Regional Authority, as from the o 0 14.1 Part Maungatapu B Block; coloured yellow, edged date hereinafter mentioned; and I also declare that this yellow, on plan. Proclamation shall take effect on and after the 13th day of o 2 38.4 Part Maungatapu B Block; coloured yellow on February 1967. plan. Situated in Blocks XI and XV, Tauranga Survey District. FIRST SCHEDULE As the same are more particularly delineated on the plan NORlH AUCKLAND LAND DISTRICT marked M.O.W. 20995 (S.O. 43577) deposited in the office of ALL that piece of land containing 6.6 perch~s situated in the Minister of Works at Wellington, and thereon coloured as Block XVI, Waitemata Survey District, City of Auckland, above mentioned. -

He Hīkoi Whakapono: a Journey of Faith

10 HUI-TANGURU 2019 NAUMAI Ngā Kōrero Feature WELCOM FEBRUARY 2019 11 He Hīkoi Whakapono: A Journey of Faith WelCom’s Hikoi of Faith returns to the Palmerston North Diocese as we continue to ‘Ruapehu Romans’ feature pastoral areas in the two dioceses. This year begins with a visit to Our Lady of the Joseph’s Primary School Taihape Merrilyn George Māori. This continues at the vigil for the PALMERSTON Snows Parish in the central North Island plateau area of Tongariro National Park and hill second Sunday each month on Maungarongo We have a dedicated Special Character team Pastoral worker Ann-Maree Manson-Petherick NORTH DIOCESE Marae. Our regular English Mass also has made up of Year 8 students. There are a variety country areas around Taihape. Our Lady of the Snows includes a number of churches and Principal communities from Ohakune, Raetihi, Waiouru, Taihape to Managaweka, several marae, many parts and music in Māori, thanks to the of activities they take part in both at school and While Europeans began settling on tussock skills of our music ministry. around the community, including supporting and St Joseph’s Catholic Primary School in Taihape. The district is renowned for year- land to graze sheep around Karioi in the There have been many changes over the years Our school is very fortunate to be located classes in class prayers and school liturgies; ARCHDIOCESE OF WELLINGTON round outdoor pursuits and is economically driven by tourism, farming, market gardening, 1860s (between Ohakune and Waiouru), the with property, buildings and personnel, but the just outside of Taihape amongst beautiful working alongside the junior students; baking forestry, and the Waiouru Military Camp and museum. -

Tongariro Northern Circuit Brochure

TONGARIRO NORTHERN CIRCUIT Duration: 3 – 4 days Great Walks season: Distance: 45 km (loop) 20 October 2017 – 30 April 2018 TONGARIRO ELEVATION PROFILE & TRACK GUIDE Oturere NORTHERN 1800 m 26 bunks 7 campsites CIRCUIT 1600 m Mangatepopo 20 bunks 7 campsites 1400 m From alpine herbfields to forests, Whakapapa Village and tranquil lakes to desert-like 1200 m plateaux, you’ll journey through 1100 m a landscape of stark contrasts 9.4 km / 4 hr 12 km / 5 hr with amazing views at every turn in this dual World Heritage site. Winding its way past Mount Tongariro and Mount Ngauruhoe, you will be dazzled on this circuit by dramatic volcanic landscapes and New Zealand’s rich geological and ancestral past. To the north is Lake Taupo, to the east the rugged Kaimanawa Day 1: Whakapapa Village Day 2: Mangatepopo Hut to range. On a clear day you may to Mangatepopo Hut Oturere Hut even catch a glimpse of Mount Taranaki on the west coast. 4 hours, 9.4 km 5 hours, 12 km The Tongariro Northern Circuit can be Your journey begins by making You join the popular Tongariro Alpine your way across the eroded Crossing on the second day, crossing walked in either direction. The track is plains of the Tongariro volcanic remnants of lava flows and climbing well marked and signposted, but some complex, a series of explosion steeply up Te Arawhata to the expansive sections may be steep, rough or muddy. craters and volcanic cones and Red Crater. Here you’ll be dazzled by This guide describes a 4-day clockwise peaks. -

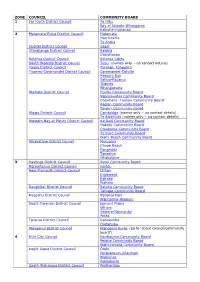

CB List by Zone and Council

ZONE COUNCIL COMMUNITY BOARD 1 Far North District Council Te Hiku Bay of Islands-Whangaroa Kaikohe-Hokianga 2 Matamata-Piako District Council Matamata Morrinsville Te Aroha Opotiki District Council Coast Otorohanga District Council Kawhia Otorohanga Rotorua District Council Rotorua Lakes South Waikato District Council Tirau (names only – no contact details) Taupo District Council Turangi- Tongariro Thames-Coromandel District Council Coromandel-Colville Mercury Bay Tairua-Pauanui Thames Whangamata Waikato District Council Huntly Community Board Ngaruawahia Community Board Onewhero -Tuakau Community Board Raglan Community Board Taupiri Community Board Waipa District Council Cambridge (names only – no contact details) Te Awamutu (names only – no contact details) Western Bay of Plenty District Council Katikati Community Board Maketu Community Board Omokoroa Community Board Te Puke Community Board Waihi Beach Community Board Whakatane District Council Murupara Ohope Beach Rangitaiki Taneatua Whakatane 3 Hastings District Council Rural Community Board Horowhenua District Council Foxton New Plymouth District Council Clifton Inglewood Kaitake Waitara Rangitikei District Council Ratana Community Board Taihape Community Board Ruapehu District Council National Park Waimarino-Waiouru South Taranaki District Council Egmont Plains Eltham Hawera-Normanby Patea Tararua District Council Dannevirke Eketahuna Wanganui District Council Wanganui Rural (go to ‘about council/community board’) 4 Hutt City Council Eastbourne Community Board Petone Community Board