Istanbul Technical University Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Masters Thesis June 2019 Spatialization Through Ge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iannis Xenakis Celebration of the Centenary of the Composer (1922-2001) by the Percussions De Strasbourg

Iannis Xenakis celebration of the centenary of the composer (1922-2001) by the Percussions de Strasbourg Pléiades at the Festival Milano Musica Percussions de Strasbourg Percussions Celebration of the centenary of the de Strasbourg IANNIS XENAKIS composer (1922-2001) by the Percussions de Strasbourg It has been said several times that, thanks to percussion, Xenakis reintroduced the problem of rhythm that was thought to have disappeared from contemporary music. Architect, engineer and composer, this genius of composition writes music whose complex and harmonious structure contrasts with the explosive energy that comes out of it. The Percussions de Strasbourg are proud to have collaborated so closely with this composer who dedicated to them the works Persephassa (1969) and Pléiades (1979), which have become a must in the field of percussion. Idmen A and B (1985) is also dedicated to the Percussions de Strasbourg. Psappha (1975) and Rebonds A and B (1987-88) are solos that appear in our repertoire as well as the trio Okho (1989). Minh-Tâm Nguyen, artistic director of the Percussions de Strasbourg Xenakis and the Percussions de Strasbourg, 1984 2021: 20th death anniversary of the composer 2022: Centenary of the birth of the composer ON TOUR Pléiades (1979) - intermission - Persephassa (1969) immersive concert for 6 percussionists July 2021, Reggia di Caserta, Naples, Italy 19th of March 2022, Philharmonie, Paris, France 10th of April 2022, Megaron Concert Hall, Athens, Greece 12th of April 2022, Thessaloniki Concert Hall, Thessaloniki, Greece -

00 Title Page

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture SPATIALIZATION IN SELECTED WORKS OF IANNIS XENAKIS A Thesis in Music Theory by Elliot Kermit-Canfield © 2013 Elliot Kermit-Canfield Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2013 The thesis of Elliot Kermit-Canfield was reviewed and approved* by the following: Vincent P. Benitez Associate Professor of Music Thesis Advisor Eric J. McKee Associate Professor of Music Marica S. Tacconi Professor of Musicology Assistant Director for Graduate Studies *Signatures are on file in the School of Music ii Abstract The intersection between music and architecture in the work of Iannis Xenakis (1922–2001) is practically inseparable due to his training as an architect, engineer, and composer. His music is unique and exciting because of the use of mathematics and logic in his compositional approach. In the 1960s, Xenakis began composing music that included spatial aspects—music in which movement is an integral part of the work. In this thesis, three of these early works, Eonta (1963–64), Terretektorh (1965–66), and Persephassa (1969), are considered for their spatial characteristics. Spatial sound refers to how we localize sound sources and perceive their movement in space. There are many factors that influence this perception, including dynamics, density, and timbre. Xenakis manipulates these musical parameters in order to write music that seems to move. In his compositions, there are two types of movement, physical and apparent. In Eonta, the brass players actually walk around on stage and modify the position of their instruments to create spatial effects. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Vagopoulou, Evaggelia Title: Cultural tradition and contemporary thought in Iannis Xenakis's vocal works General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Cultural Tradition and Contemporary Thought in lannis Xenakis's Vocal Works Volume I: Thesis Text Evaggelia Vagopoulou A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordancewith the degree requirements of the of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, Music Department. -

Exploring Xenakis Performance, Practice, Philosophy

Exploring Xenakis Performance, Practice, Philosophy Edited by Alfia Nakipbekova University of Leeds, UK Series in Music Copyright © 2019 Vernon Press, an imprint of Vernon Art and Science Inc, on behalf of the author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Music Library of Congress Control Number: 2019931087 ISBN: 978-1-62273-323-1 Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image: Photo of Iannis Xenakis courtesy of Mâkhi Xenakis. Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Table of contents Introduction v Alfia Nakipbekova Part I - Xenakis and the avant-garde 1 Chapter 1 ‘Xenakis, not Gounod’: Xenakis, the avant garde, and May ’68 3 Alannah Marie Halay and Michael D. -

Iannis Xenakis, Roberta Brown, John Rahn Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol

Xenakis on Xenakis Author(s): Iannis Xenakis, Roberta Brown, John Rahn Source: Perspectives of New Music, Vol. 25, No. 1/2, 25th Anniversary Issue (Winter - Summer, 1987), pp. 16-63 Published by: Perspectives of New Music Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/833091 Accessed: 29/04/2009 05:06 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=pnm. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Perspectives of New Music is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Perspectives of New Music. http://www.jstor.org XENAKIS ON XENAKIS 47W/ IANNIS XENAKIS INTRODUCTION ITSTBECAUSE he wasborn in Greece?That he wentthrough the doorsof the Poly- technicUniversity before those of the Conservatory?That he thoughtas an architect beforehe heardas a musician?Iannis Xenakis occupies an extraodinaryplace in the musicof our time. -

C:\Users\Hhowe\Dropbox\Courses

Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001): Catalogue of Musical Compositions (from www.iannis-xenakis.org) Seven untitled pieces, Menuet, Air populaire, Allegro molto, Mélodie, Andante : 1949-50; piano, unpublished. Six Chansons : 1951; piano; 8’. Dhipli Zyia :1952; duo (vln, vlc); 5’30. Zyia :1952; 2 versions: a) soprano, men’s chorus (minimum 10) and duo (fl, pno); b) soprano, fl, pno; 10’. Trois poèmes : 1952; narrator and pno; unpublished. La colombe de la paix : 1953; alto and 4-voice mixed chorus; unpublished. Anastenaria. Procession aux eaux claires : 1953; mixed chorus (30), men chorus (15) and orchestra (62); 11’. Anastenaria. Le Sacrifice :1953; orchestra (51); 6’. Stamatis Katotakis, chanson de table : 1953; voice and 3-voice men chorus; unpublished. Metastasis : 1953-4; orchestra (60); 7’ Pithoprakta :1955-6; string orchestra (46), 2 trb and perc; 10’ Achorripsis :1956-7; orchestra (21); 7’ Diamorphoses :1957-8; electroacoustic tape. 7’. Concret PH :1958; electroacoustic tape; 2’45". Analogiques A & B :1958-9; string ensemble (9) and electroacoustic tape; 7’30". Syrmos :1959; string ensemble (18 or 36); 14". Duel :1959; 2 orchestras (56 total) and 2 conductors; variable duration (circa 10’). Orient-Occident :1960; electroacoustic tape; 12’. Herma : 1961; for solo piano; 10’ ST/48,1-240162 :1956-62); orchestra (48); 11’ ST/10, 1-080262 : 1956-62; ensemble (10); 12’ ST/4, 1-080262 : 1956-62; string quartet; 11’ Morsima - Amorsima (ST/4, 2-030762) :1956-62); quartet (pno, vln, vlc, db); 11’ Atrées (ST/10, 3-060962) : 1956-62; ensemble (11); 15’. Stratégie : 1962; 2 orchestras (82 total) and 2 conductors; variable duration (10 to 30’) Polla ta dhina :1962; children's chorus (20) and orchestra (48); 6’ Bohor :1962; electroacoustic tape; 21’30". -

Multi-Percussion in the Undergraduate Percussion Curriculum Benjamin A

University of Miami Scholarly Repository Open Access Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-12 Multi-percussion in the Undergraduate Percussion Curriculum Benjamin A. Charles University of Miami, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Charles, Benjamin A., "Multi-percussion in the Undergraduate Percussion Curriculum" (2014). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 1324. This Open access is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI ! ! MULTI-PERCUSSION IN THE UNDERGRADUATE PERCUSSION CURRICULUM ! By Benjamin Andrew Charles ! A DOCTORAL ESSAY ! ! Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Miami in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Coral Gables,! Florida ! December 2014 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ©2014 Benjamin Andrew Charles ! All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY! OF MIAMI ! ! A doctoral essay proposal submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical! Arts ! ! MULTI-PERCUSSION IN THE UNDERGRADUATE PERCUSSION CURRICULUM! ! Benjamin Andrew Charles ! ! !Approved: ! _________________________ __________________________ -

Philippe LEROUX Y R a L a E H P O T S I R H C

Philippe LEROUX y r a l A e h p o t s i r h C : o t o h P Gérard Billaudot Éditeur Octobre 2014 P h i l i p p e L E R O U X ( 1 9 5 9 ) CATALOGUE DES ŒUVRES C ATALOGUE OF WORKS W ERKVERZEICHNIS C ATALOGO DE OBRAS 14 rue de l’Échiquier - 75010 PARIS - FRANCE Tél. : (33) 01.47.70.14.46 - Télécopie : (33) 01.45.23.22.54 www.billaudot.com [email protected] - [email protected] B I O G R A P H I E P H I L I P P E L E RO U X ( 1 9 5 9 ) Philippe Leroux entre au Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique de Paris en 1978 dans les classes d'Ivo Malec, Claude Ballif, Pierre Schäeffer et Guy Reibel où il obtient trois premiers prix. Durant cette période, il étudie également avec Olivier Messiaen, Franco Donatoni, Betsy Jolas, Jean-Claude Eloy et Iannis Xénakis. En 1993, il est nommé pensionnaire à la Villa Médicis où il séjourne jusqu'en octobre 1995. Il est l'auteur d'une soixantaine d'œuvres, symphoniques, acousmatiques, vocales, pour dispositifs électroniques, et de musique de chambre. Celles-ci lui ont été commandées par le Ministère français de la Culture, l'Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio-France, la Südwestfunk Baden-Baden, l'IRCAM, Les Percussions de Strasbourg, l'Ensemble Intercontemporain, l'Ensemble 2e2m, l'INA-GRM, le Nouvel Ensemble Moderne de Montreal, l'Ensemble Ictus, le Festival Musica, l'Ensemble BIT 20, la fondation Koussevitsky, l'Ensemble San Francisco Contemporary Music Players, l'Ensemble Athelas, l'Orchestre National de Lorraine, l'Orchestre Philharmonique de Nice, le CIRM, INTEGRA, le Festival Berlioz, ainsi que par d'autres institutions françaises et étrangères. -

Historical Backgrounds and Musical Developments of Iannis

Historical Backgrounds and Musical Developments of Iannis Xenakis’s Persephassa (1969) By Matthew Peter Teodori, BM, MM Lecture Recital Document Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin 2012 Historical Backgrounds and Musical Developments of Iannis Xenakis’s Persephassa (1969) Western music written solely for percussion instruments began appearing in earnest in the 1930s. The budding genre would see tremendous growth in the Americas up until the end of World War II. Following the war, percussive evolution would find its way into academia and be championed by a new breed of percussionist/composer. The first professional Western percussion ensemble, Les Percussions de Strasbourg, would emerge in 1962, forever altering the history of percussion chamber music. The six French percussionists would begin to commission works from the foremost avant-garde musical minds in Europe. One such commission, Iannis Xenakis‟s Persephassa (1969), stands as a singular masterpiece for its comprehensive use of rhythm, spatial considerations and extraordinary length. Early Percussion Repertoire One of the earliest pieces of percussion music was composed by Frenchman Edgard Varèse in 1931. Ionisation is a work of remarkable deftness and imagination, utilizing thirteen players on forty-four instruments. The score‟s ninety-one measures last only six minutes, yet, despite its brevity, Ionisation is generally considered to be one of the finest works for percussion instruments ever written. What must be remembered, however, is that Varèse‟s work was not the first piece of its kind. -

Περίληψη : a Music Composer of Greek Origin, Coming from a Family of the Greek Diaspora

IΔΡΥΜA ΜΕΙΖΟΝΟΣ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ Συγγραφή : Ροβίθη Χαρά Μετάφραση : Αμπούτη Αγγελική Για παραπομπή : Ροβίθη Χαρά , "Xenakis Iannis", Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού, Εύξεινος Πόντος URL: <http://www.ehw.gr/l.aspx?id=11573> Περίληψη : A music composer of Greek origin, coming from a family of the Greek Diaspora. During his lifetime, being as a participant of the social, political and cultural life in the years following the Second World War, he followed a course of research and creation serving his vision of art. Iannis Xenakis produced a rich musical, architectural and auctorial work which made him one of the most important progressive creators of the 20th century. Τόπος και Χρόνος Γέννησης 29th of May, 1922 ? (or 1921), Brăila, Romania. Τόπος και Χρόνος Θανάτου 4th of February, 2001, Paris. Κύρια Ιδιότητα Architect, mechanic, composer. 1. The First Years-Basic Studies Iannis Xenakis was born in Brăila of Romania, on the 29th of May, 1922 (the date is uncertain as it is probable that he was born in 1921) of parents who were members of the Greek Diaspora. His father, Klearchos, director of a British import-export company, came from Euboea, and his mother, Fotini Pavlou, came from the island of Limnos. Iannis Xenakis had two younger brothers, Kosmas, an urban planner and a painter, and Iasonas, a philosophy professor. Xenakis was introduced to music by his mother, who was a pianist. It is said that during his early childhood his mother gave him as a present a flute encouraging him to get involved in music. When he was five years old, his mother died from measles and the three children were brought up by French, English and German governesses. -

Woodblock (Instrument)

Woodblock (instrument) A wood block (also spelled as a single word, woodblock) is a small slit Woodblock drum made from a single piece of wood and used as a percussion instrument. The term generally signifies the Western orchestral instrument, though it is related to the ban time-beaters used by the Han Chinese, which is why the Western instrument is sometimes referred to as Chinese woodblock. Alternative names sometimes used in ragtime and jazz are clog box and tap box. In orchestral music scores, wood blocks may be indicated by the French bloc de bois or tambour de bois, German Holzblock or Holzblocktrommel, or Italian cassa di legno (Blades and Holland 2001). Percussion instrument The orchestral wood block of the West is generally made from teak or Other names Woodblock, another hardwood. The dimensions of this instrument vary, although it is Chinese either a rectangular or cylindrical block of wood with one or sometimes woodblock, Clog two longitudinal cavities (Blades and Holland 2001). It is played by box, Tap box striking it with a stick, which produces a sharp crack (Montagu 2002b). Classification Percussion Alternatively, a rounder mallet, soft or hard, may be used, which produces Hornbostel 111.2 a deeper-pitched and fuller "knocking" sound. –Sachs (Percussion In a drum kit, a wood block was traditionally mounted on a clamp fixed to classification idiophones) the top of the rear rim of the bass drum. Related instruments slit drum, temple blocks, log drums, Related instruments muyu, jam block, simantra Log drums made from hollowed logs, and slit drums made from bamboo, are used in Africa and the Pacific Islands. -

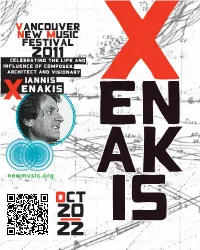

2011 Celebrating the Life and Influence of Composer, Architect and Visionary X Iannis Enakis

VANCOUVER NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL2011 Celebrating the life and influence of composer, architect and visionary X Iannis enakis newmusic.org OCT 20 22 Listening to the music of Iannis Xenakis…is like being flung ALL EVENTS AT back into some fierce atavistic SCOTIABANK world before culture existed… DANCE Such magnificently innocent music is bound to be out of place in our oblique, knowing age, so obsessed with its past, so CENTRE fastidiously ironic, so concerned, in its art, to layer ambiguity upon ambiguity. That Xenakis could have denied this pervasive cultural trend for 40 years is an amazing feat. Perhaps only 677 someone who had no need of the western tradition, someone whose roots lay elsewhere, could have done it. DAVIE ST. from IannIS XenakIS’ obITuary, by Ivan HeweTT, ” ShOwS 8PM PublISHed February 5, 2001 In The Guardian Celebrating the work and influence of Something one of the most original and prolific creative figures of the 20th century, Rich and VNM’s 2011 Festival honours the 10th StrangE anniversary of the death of composer, FIlM architect and visionary Iannis Xenakis. SCREENINg Xenakis’ works span every media and Oct21- 6PM numerous approaches, from orchestral to electroacoustic to multi-media. ICKETS Also a mathematician, experimental $20 regular • $15 students + seniors engineer and architect, theoretician, sikora’s classical records brown Paper Tickets $ $ educator, and author, Xenakis was a 3-NIGHT Pass 50• 35 432 w. Hastings st. brownpapertickets.ca avaIlable oNly through true renaissance figure. 1-800-838-3006 vaNcouver New MusIc 604.633.0861 & aT the door Xenakis Project Amof tehericas Black CMYK Pantone OCT THURSDAY 20 James harley is a Canadian composer presently 8PM based in ontario, where he teaches digital Music at lorI FreedMAN (Montreal) IANNIS XeNAKIS mini-polytope 01 the university of Guelph.