To Type Report Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Rail Continues Its Growth with Acquisition of Carolina Coastal Railway

Press release 3 February 2020 Regional Rail continues its growth with acquisition of Carolina Coastal Railway 3i-backed Regional Rail, a leading owner and operator of short-line freight railroads and rail-related businesses in the U.S., has agreed to acquire Carolina Coastal Railway, Inc. (“Carolina Coastal”) which operates 180 miles of freight railroad in North Carolina and South Carolina, subject to authorisation from the Surface Transportation Board. Carolina Coastal provides freight transportation and car-storage services to over 45 blue-chip customers, operating across a variety of end markets (including aggregates, food & agriculture, chemicals and metals), primarily in eastern North Carolina. Al Sauer, CEO, Regional Rail, commented: “Carolina Coastal is a great fit with Regional Rail as it benefits from an attractive mix of industrial customers and further diversifies our existing freight-rail platform from an end-market and geographic perspective. We look forward to welcoming all of the Carolina Coastal employees to Regional Rail and working with them to continue the company’s successful growth.” Doug Golden, President, Carolina Coastal, commented: “I had been looking for the right partner to continue our legacy in North Carolina and am pleased that Carolina Coastal is becoming part of the Regional Rail family. I have known Al for many years. He and his team have been great to work with on this transaction, and I believe they will be good partners in supporting our employees, customers, and all future developments.” Rob Collins, Managing Partner, 3i North American Infrastructure, commented: “We’re delighted to announce a second acquisition for Regional Rail as the company continues to consolidate its position in the U.S. -

Statewide Logistics Plan for North Carolina

Statewide Logistics Plan for North Carolina An Investigation of the Issues with Recommendations for Action APPENDICES By George F. List, Ph.D, P.E. P.I. and Head, Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering North Carolina State University Robert S. Foyle, P.E. Co-P.I. and Associate Director, ITRE North Carolina State University Henry Canipe Senior Manager TransTech Management, Inc. John Cameron, Ph.D. Managing Partner TransTech Management, Inc. Erik Stromberg Ports and Harbors Practice Leader Hatch, Mott, MacDonald LLC For the North Carolina Office of State Budget and Management May 13, 2008 Appendices Appendix A: Powerpoint Slide Sets Presentations include: Tompkins Associates North Carolina Statewide Logistics Proposal North Carolina Statewide Logistics Plan Cambridge Systematics Freight Demand and Logistics – Trends and Issues Highway Freight Transportation – Trends and Issues Rail Freight Transportation – Trends and Issues Waterborne Freight Transportation – Trends and Issues State DOTs and Freight – Trends and Issues Virginia Statewide Multimodal Freight Study - Phase I Overview Global Insight Shifts in Global Trade Patterns – Meaning for North Carolina 5/5/2008 North Carolina Statewide Logistics Proposal Presented to: North Carolina State University Project Team Charlotte, NC March 13, 2008 Caveat… This presentation and discussion is from the Shipper’s perspective… ASSO C I ATES CONFIDENTIAL — Use or disclosure of this information is restricted. 2 1 5/5/2008 North American Port Report (1/08) A majority of the Supply Chain Consortium respondents to the North American Port Report survey believe that their supply chain network is not optimal with respect to the ports used for their ocean freight. Significant opportunities exist from getting all aspects of the supply chain aligned to optimizing costs and customer service. -

2012 Piedmont Triad Region Freight Movement Report

2012 Piedmont Triad Region Freight Movement Report September 12, 2012 Report Prepared by: C. David Hauser, Project Manager Transportation Institute NC A&T State University In Partnership with the: The Piedmont Authority for Regional Transportation, and In cooperation with The Burlington-Graham Metropolitan Planning Organization, The Greensboro Metropolitan Planning Organization, The High Point Metropolitan Planning Organization, and The Winston-Salem Metropolitan Planning Organization Table of Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose of chapter 1.2 Relevance to the Transportation System and the Plan 2 Existing Conditions and Trends 2.1 Entire Freight System: Statewide and Regional Conditions and Trend 2.2 Highway Freight: National Conditions and Trends 2.3 Highway Freight: Statewide and Regional Conditions and Trends 2.4 Highway Freight: Conditions and Trends in the Piedmont Triad Study Area 2.5 Rail Freight: National Conditions and Trends 2.6 Rail Freight: Statewide and Regional Conditions and Trends 2.7 Rail Freight: Condition and Trends in the Piedmont Triad Study Area 3 Current and Future Issues 3.1 Entire Freight System: Statewide and Regional Current and Future issues 3.2 Highway Freight: National Current and Future Issues 3.3 Highway Freight: Statewide and Regional Current and Future Issues 3.4 Rail Freight: National Current and Future Issues 3.5 Rail Freight: Statewide and Regional Current and Future Issues 3.6 Freight System: Current and Future Issues Within the Piedmont Triad Study Area 4 NC ports 5 Airports 5.1 Piedmont Triad International Airport 5.2 Smith Reynolds Airport 5.3 Additional Piedmont Triad Regional Airports 6 Safety and Security 7 Recommendations for Piedmont Triad Study Area 7.1 Truck Route Recommendations 7.2 Summary Recommendations 2012 Piedmont Triad Region Freight Movement Report 1 Introduction 1.1 Purpose of chapter Freight movement is critical to an advanced industrial economy, and the ease of freight movement is a component of a region’s economic competitiveness. -

Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP) 2040

Metropolitan Transportation Plan (MTP) 2040 4.5 RAIL TRANSPORTATION The North Carolina Railroad between Greensboro and Raleigh is an important transportation link. The communities along the corridor and their economies are growing. Improvements to the railroad are important for mobility, freight movement, and safety. Much of the corridor remains on the alignment laid out in the mid-1800s, which envisioned maximum train speeds of 45 mph. As part of the federally- designated Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor, this segment of railroad will need significant improvements for capacity and speed (NCDOT). Passenger Rail Three AMTRAK trains operate through the historic passenger rail terminal in High Point (Carolinian-Piedmont Schedule, 2012) (Crescent Schedule, 2012). Table 4.5-1 shows the trains, scheduled departure time, route and direction of the trains. To support passenger rail service, the Piedmont Authority for Regional Transportation provides connector service from the AMTRAK station to Winston-Salem for trains 73, 74, and 76. Time schedules and fare information are available at: http://www.bytrain.org/docs/5AmtrakConnectorweb.pdf. Train Departure Time Route Direction Name Number Crescent 19 12:39 am NY-HP-DC-NO SB Piedmont 73 8:34 am Ral-HP-Clt SB Piedmont 75 1:34 pm Ral-HP-Clt SB Carolinian 79 6:48 pm NY-Ral-HP-CLT SB Crescent 20 3:16 am NO-HP-DC-NY NB Carolinian 80 8:17 am Clt-HP-Ral-NY NB Piedmont 74 1:14 pm Ral-HP-Clt NB Piedmont 76 6:29 pm Ral-HP-Clt NB TABLE 4.5-1 PASSENGER TRAINS USING THE HISTORIC HIGH POINT DEPOT Figure 4.5-1 slightly different view of the train schedules through High Point. -

North Carolina Railroad System Map-August 2019

North Carolina !( Railroad System Clover !( !( South Boston Franklin Danville !( !( !( Mount Airy !( !( Clarksville Alleghany Eden !( Mayo Currituck Camden Ashe Hyco !( !( Gates !( Roanoke !( Conway Surry YVR Norlina Weldon R Stokes Rockingham Granville Rapids Elizabeth CA Caswell Person Vance !( Hertford City !( Roxboro Northampton !( Reidsville !( !( YVRR Oxford Henderson Warren Halifax !(Ahoskie VA Rural NC Watauga Wilkes !( Pasquotank Hall CA !( !( Erwin!( Yadkin Orange Kelford Chowan Perquimans North Durham Guilford !( N Franklin Avery Wilkesboro Forsyth !( Burlington Butner !( CDOT Mitchell ! Bertie !( Winston ! !(Hillsborough Franklinton Edenton Salem Greensboro Nash Caldwell ! Durham Rocky Midway !( High !( Wake Forest CLNA !(Taylorsville Iredell Davie ! Alamance !( ! Mount Yancey Lenoir Davidson Spring ! Madison !( Point Carrboro !( !( Tarboro Washington Alexander A Wake Burke C R Hope !( W C C T Zebulon Plymouth Tyrrell Y O !( Edgecombe !( Statesville !( D Cary CLNA Middlesex Lexington C !( !( !( Parmele Dare N ! W ! W Martin s Buncombe !( Hickory ! S !( S ain Chatham Raleigh Wendell t S n McDowell !( Morganton S !(Apex ! ou CMLX Marion !( k !Wilson M c rk Asheboro NHVX ky a Haywood !( !( o Pitt o P T Newton ! A l Salisbury n !( Wilson f m a O New Hll l !(Clayton N S n Old Fort Catawba !( L CLNA D t o m i CMIZ Denton u a t !( CLNA C C Greenville re a BLU Rowan Randolph u !( N Asheville G G N C !( W !( !( Belhaven Swain !( S !( Fuquay-Varina !( S !( Waynesville BLU A ! Washington !( GSM Lincoln Lincolnton ! T Selma Chocowinity -

Class I Railroad Annual Report

OEEAA – R1 OMB Clearance No. 2140-0009 Expiration Date 12-31-2022 Class I Railroad Annual Report Norfolk Southern Combined Railroad Subsidiaries Three Commercial Place Norfolk, VA 23510-2191 Full name and address of reporting carrier Correct name and address if different than shown (Use mailing label on original, copy in full on duplicate) To the Surface Transportation Board For the year ending December 31, 2019 Road Initials: NS Rail Year: 2019 ANNUAL REPORT OF NORFOLK SOUTHERN COMBINED RAILROAD SUBSIDIARIES ("NS RAIL") TO THE Surface Transporation Board FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2019 Name, official title, telephone number, and office address of officer in charge of correspondence with the Board regarding this report: (Name) Jason A. Zampi (Title) Vice President and Controller (Telephone number) (757) 629-2680 (Area Code) (Office address) Three Commercial Place Norfolk, Virginia 23510-2191 (Street and number, city, state, and ZIP code) Railroad Annual Report R-1 NOTICE 1. This report is required for every class I railroad operating within the United States. Three copies of this Annual Report should be completed. Two of the copies must be filed with the Surface Transportation Board, Office of Economics, Environmental Analysis, and Administration, 395 E Street, S.W. Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20423, by March 31 of the year following that for which the report is made. One copy should be retained by the carrier. 2. Every inquiry must be definitely answered. Where the word "none" truly and completely states the fact, it should be given as the answer. If any inquiry is inapplicable, the words "not applicable" should be used. -

North Carolina Rail Fast Facts for 2019 Freight Railroads …

Freight Railroads in North Carolina Rail Fast Facts For 2019 Freight railroads ….............................................................................................................................................................23 Freight railroad mileage …..........................................................................................................................................2,847 Freight rail employees …...............................................................................................................................................1,966 Average wages & benefits per employee …...................................................................................................$121,570 Railroad retirement beneficiaries …......................................................................................................................9,800 Railroad retirement benefits paid ….....................................................................................................................$234 million U.S. Economy: According to a Towson University study, in 2017, America's Class I railroads supported: Sustainability: Railroads are the most fuel efficient way to move freight over land. It would have taken approximately 4.6 million additional trucks to handle the 82.7 million tons of freight that moved by rail in North Carolina in 2019. Rail Traffic Originated in 2019 Total Tons: 13.2 million Total Carloads: 284,600 Commodity Tons (mil) Carloads Chemicals 3.2 33,800 Nonmetallic Minerals 3.1 30,200 Intermodal -

Short Line Railcar Storage Locations

Short Line Car Storage Directory State Short Short Line Name Contact Name E-Mail Phone Car Hazmat Hazmat TIH/PIH TIH/PIH Restrictions Line Spots Loads Residue Loads Residue SCAC (Max) (empty but not cleaned) AL RJAL RJ Corman Childersburg Adam Boyles [email protected] 859 314-0891 42 YES YES YES YES AL SQSC Sequatchie Valley Railroad Byron Clinton [email protected] 931 580-7375 750 YES YES NO YES AL ATN Alabama & Tennessee River Railway, LLC Chris Richter [email protected] 920 209-0118 260 YES YES NO NO AL TASD Terminal Railway, Alabama State Docks Cliff Melton [email protected] 251 408-7077 100 NO NO NO NO AL AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 130 NO YES NO NO AL CAGY Columbus & Greenville Railway Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 440 YES YES NO NO AL COEH Conecuh Valley Railroad Co., Inc. Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 300 NO YES NO NO AL MNBR Meridian & Bigbee Railroad Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 240 NO YES NO NO AL TNHR Three Notch Railroad Co. Inc. Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 30 YES YES NO NO AL WGCR Wiregrass Central Railroad Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 100 NO YES NO NO AL EARY Eastern Alabama Railway Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 135 NO YES NO NO AL ALAB Alabama Railroad Co. Nathan Johns [email protected] 309 605-0119 300 YES YES NO NO 263k restriction AL ALE Alabama Export Railroad Meaghan Davis [email protected] 228 474-0711 80 NO NO NO NO CT CNZR Central New England Railroad Deb Belliveau [email protected] 860 666-1030 88 NO NO NO NO 263k restriction CT CSO Connecticut Southern Railroad Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 150 NO NO NO NO 263k restriction, Plate F CT NECR New England Central Railroad Kevin Phillips [email protected] 904 562-0692 400 NO NO NO NO CT HRRC Housatonic Railroad Co., Inc. -

Class I Railroad Annual Report

ACAA – R1 Class I Railroad Annual Report Norfolk Southern Combined Railroad Subsidiaries Three Commercial Place Norfolk, VA 23510-2191 Correct name and address if different than shown Full name and address of reporting carrier (Use mailing label on original, copy in full on duplicate) To The Surface Transportation Board For the Year Ending December 31, 2008 Road Initials: NS Rail Year: 2008 ANNUAL REPORT OF NORFOLK SOUTHERN COMBINED RAILROAD SUBSIDIARIES ("NS RAIL") TO THE Surface Transporation Board FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2008 Name, official title, telephone number, and office address of officer in charge of correspondence with the Board regarding this report: (Name) C. H. "Jake" Allison, Jr. (Title) Vice President and Controller (Telephone number) (757) 629-2765 (Area Code) (Office address) Three Commercial Place, Norfolk, VA 23510-2191 (Street and number, city, state, and ZIP code) Railroad Annual Report R-1 (This page intentionally left blank) Road Initials: NS Rail Year: 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Schedule Page Schedules Omitted by Respondent A1 Identity of Respondent B2 Voting Powers and Elections C3 Comparative Statement of Financial Position 200 5 Results of Operations 210 16 Retained Earnings 220 19 Capital Stock 230 20 Statement of Cash Flows 240 21 Working Capital 245 23 Investments and Advances - Affiliated Companies 310 26 Investments in Common Stock of Affiliated Companies 310A 30 Road Property and Equipment and Improvements to Leased Property and Equipment 330 32 Depreciation Base and Rates - Road and Equipment Owned -

Class I Railroad Annual Report

OEEAA – R1 OMB Clearance No. 2140-0009 Expiration Date 12-31-2022 Class I Railroad Annual Report Norfolk Southern Combined Railroad Subsidiaries Three Commercial Place Norfolk, VA 23510-2191 Full name and address of reporting carrier Correct name and address if different than shown (Use mailing label on original, copy in full on duplicate) To the Surface Transportation Board For the Year Ending December 31, 2020 Road Initials: NS Rail Year: 2020 ANNUAL REPORT OF NORFOLK SOUTHERN COMBINED RAILROAD SUBSIDIARIES ("NS RAIL") TO THE SURFACE TRANSPORTATION BOARD FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2020 Name, official title, telephone number, and office address of officer in charge of correspondence with the Board regarding this report. (Name) Clyde H. "Jake" Allison Jr. (Title) Vice President and Controller (Telephone number) (757) 629-2680 (Area code) (Telephone number) (Office address) Three Commercial Place Norfolk, Virginia 23510-2191 (Street and number, city, state, and ZIP code) Railroad Annual Report R-1 NOTICE 1. This report is required for every class I railroad operating within the United States. Three copies of this Annual Report should be completed. Two of the copies must be filed with the Surface Transportation Board, Office of Economics, Environmental Analysis, and Administration, 395 E Street, S.W. Suite 1100, Washington, DC 20423, by March 31 of the year following that for which the report is made. One copy should be retained by the carrier. 2. Every inquiry must be definitely answered. Where the word "none" truly and completely states the fact, it should be given as the answer. If any inquiry is inapplicable, the words "not applicable" should be used. -

Table of Contents I

FEASIBILITY STUDY - SR 1001 (LAMM ROAD) Table of Contents I. General Description .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Background and Need for the Project ...................................................................................................... 1 III. Traffic and Safety ................................................................................................................................... 1 IV. Description of the Widening Alternative ............................................................................................... 6 V. Community Issues .................................................................................................................................... 6 VI. Natural Environment Issues .................................................................................................................... 7 VII. Recommendations / Additional Comments ........................................................................................ 10 Tables Table 1 - Mainline Level-of-Service Summary Table 2 - Intersection Level-of-Service Summary Table 3 - Lamm Road Intersections: Crash Summary (August 2005 – June 2008) Table 4 - Lamm Road Intersections Crash Frequency by Type Figures Figure 1 – Vicinity Map Figure 2 – Project Location Map Figure 3 – Traffic Forecast Figure 4 – Recommended Lane Geometry (with Existing Lanes and Traffic Control) Figure 5 – Typical Sections and Functional Roadway Designs -

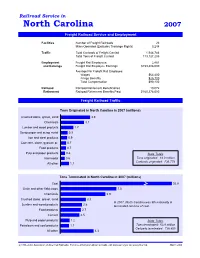

NC Railroad Statistics (2007)

Railroad Service in North Carolina 2007 Freight Railroad Service and Employment Facilities Number of Freight Railroads 23 Miles Operated (Excludes Trackage Rights) 3,248 Traffic Total Carloads of Freight Carried 1,544,783 Total Tons of Freight Carried 113,127,205 Employment Freight Rail Employees 2,481 and Earnings Freight Rail Employee Earnings $159,886,000 Average Per Freight Rail Employee: Wages $64,400 Fringe Benefits $25,700 Total Compensation $90,100 Railroad Railroad Retirement Beneficiaries 10,072 Retirement Railroad Retirement Benefits Paid $160,378,000 Freight Railroad Traffic Tons Originated in North Carolina in 2007 (millions) Crushed stone, gravel, sand 3.9 Chemicals 3.1 Lumber and wood products 1.7 Scrap paper and scrap metal 0.9 Iron and steel products 0.9 Concrete, stone, gypsum pr. 0.7 Food products 0.7 Pulp and paper products 0.6 State Totals Intermodal 0.6 Tons originated: 14.0 million Carloads originated: 236,779 All other 1.1 Tons Terminated in North Carolina in 2007 (millions) Coal 32.8 Grain and other field crops 7.3 Chemicals 5.9 Crushed stone, gravel, sand 3.3 In 2007, North Carolina was 9th nationally in Lumber and wood products 2.8 terminated rail tons of coal. Food products 2.7 Cement 2.5 Pulp and paper products 1.2 State Totals Petroleum and coal products 1.1 Tons terminated: 63.9 million Carloads terminated: 738,850 All other 4.3 © 1993–2009, Association of American Railroads. For more information about railroads, visit www.aar.org or call 202-639-2100. March 2009 Freight Railroads in North Carolina 2007 Miles of Railroad North Carolina Miles Operated Operated in North Carolina Totals Number Excluding Including Class I Railroads of Freight Trackage Trackage CSX Transportation 1,121Railroads Rights Rights Norfolk Southern Corp.