Tick-Borne Encephalitis Virus Complex • Aerosol Hazard in Laboratory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 New Jersey Reportable Communicable Disease Report (January 3, 2016 to December 31, 2016) (Excl

10:34 Friday, June 30, 2017 1 2016 New Jersey Reportable Communicable Disease Report (January 3, 2016 to December 31, 2016) (excl. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, HIV/AIDS and Tuberculosis) (Refer to Technical Notes for Reporting Criteria) Case Jurisdiction Disease Counts STATE TOTAL AMOEBIASIS 98 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX 0 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX - CUTANEOUS 0 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX - INHALATION 0 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX - INTESTINAL 0 STATE TOTAL ANTHRAX - OROPHARYNGEAL 0 STATE TOTAL BABESIOSIS 174 STATE TOTAL BOTULISM - FOODBORNE 0 STATE TOTAL BOTULISM - INFANT 10 STATE TOTAL BOTULISM - OTHER, UNSPECIFIED 0 STATE TOTAL BOTULISM - WOUND 1 STATE TOTAL BRUCELLOSIS 1 STATE TOTAL CALIFORNIA ENCEPHALITIS(CE) 0 STATE TOTAL CAMPYLOBACTERIOSIS 1907 STATE TOTAL CHIKUNGUNYA 11 STATE TOTAL CHOLERA - O1 0 STATE TOTAL CHOLERA - O139 0 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE 4 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - FAMILIAL 0 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - IATROGENIC 0 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - NEW VARIANT 0 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - SPORADIC 2 STATE TOTAL CREUTZFELDT-JAKOB DISEASE - UNKNOWN 1 STATE TOTAL CRYPTOSPORIDIOSIS 198 STATE TOTAL CYCLOSPORIASIS 29 STATE TOTAL DENGUE FEVER - DENGUE 43 STATE TOTAL DENGUE FEVER - DENGUE-LIKE ILLNESS 3 STATE TOTAL DENGUE FEVER - SEVERE DENGUE 4 STATE TOTAL DIPHTHERIA 0 STATE TOTAL EASTERN EQUINE ENCEPHALITIS(EEE) 1 STATE TOTAL EBOLA 0 STATE TOTAL EHRLICHIOSIS/ANAPLASMOSIS - ANAPLASMA PHAGOCYTOPHILUM (PREVIOUSLY HGE) 109 STATE TOTAL EHRLICHIOSIS/ANAPLASMOSIS - EHRLICHIA CHAFFEENSIS (PREVIOUSLY -

Tick-Transmitted Diseases

Deer tick-transmitted infections zoonotic in the eastern U.S. •Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato): erythema migrans rash, fever, chills, muscle aches; can progress to arthritis or neurologic signs – 200-500 cases/100,000/year •Babesiosis (Babesia microti): malaria like, fever, chills, muscle aches, fatigue, hemolysis/anemia– 100-200 cases/100,000/year •Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis/anaplasmosis (Anaplasma phagocytophilum): fever, chills, muscle aches, headache—50-100 cases/100,000/year •Borrelia miyamotoi disease (BMD): fever, chills, muscle aches, headache – 50-100 cases/100,000/year •Deer tick virus fever/encephalitis: fever, headache, confusion, seizures– 1-5 cases/100,000/ year Erythema migrans: not just a “bulls-eye” Courtesy of Tim Lepore MD, Nantucket Cottage Hospital Life cycle of deer ticks…critical to develop interventions 40%-70% infection rate 10%-30% infection rate Grace period: Adaptations to extended life cycle Borrelia burgdorferi: 24-48 hours (upregulation of OspC, migration from gut to salivary glands) Babesia microti: 48-62 hours (sporogony from undifferentiated salivary sporoblast) Anaplasma phagocytophilum: 24-36 hours (acquisition of “slime layer”?) Tickborne encephalitis virus: none “Restore the risk landscape to what it was before 1980” The main drivers for emergence of the Lyme disease epidemic: 1905 Pout’s Pond, Deforestation, reforestation: Nantucket dominance of successional habitat Increased development and recreational use in reforested sites Burgeoning deer herds 1986 http://www.ct.gov/caes/lib/caes/documents/publications/bulletins/b1010.pdf -

Transmission and Evolution of Tick-Borne Viruses

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Transmission and evolution of tick-borne viruses Doug E Brackney and Philip M Armstrong Ticks transmit a diverse array of viruses such as tick-borne Bourbon viruses in the U.S. [6,7]. These trends are driven encephalitis virus, Powassan virus, and Crimean-Congo by the proliferation of ticks in many regions of the world hemorrhagic fever virus that are reemerging in many parts of and by human encroachment into tick-infested habitats. the world. Most tick-borne viruses (TBVs) are RNA viruses that In addition, most TBVs are RNA viruses that mutate replicate using error-prone polymerases and produce faster than DNA-based organisms and replicate to high genetically diverse viral populations that facilitate their rapid population sizes within individual hosts to form a hetero- evolution and adaptation to novel environments. This article geneous population of closely related viral variants reviews the mechanisms of virus transmission by tick vectors, termed a mutant swarm or quasispecies [8]. This popula- the molecular evolution of TBVs circulating in nature, and the tion structure allows RNA viruses to rapidly evolve and processes shaping viral diversity within hosts to better adapt into new ecological niches, and to develop new understand how these viruses may become public health biological properties that can lead to changes in disease threats. In addition, remaining questions and future directions patterns and virulence [9]. The purpose of this paper is to for research are discussed. review the mechanisms of virus transmission among Address vector ticks and vertebrate hosts and to examine the Department of Environmental Sciences, Center for Vector Biology & diversity and molecular evolution of TBVs circulating Zoonotic Diseases, The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, in nature. -

Generic Amplification and Next Generation Sequencing Reveal

Dinçer et al. Parasites & Vectors (2017) 10:335 DOI 10.1186/s13071-017-2279-1 RESEARCH Open Access Generic amplification and next generation sequencing reveal Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus AP92-like strain and distinct tick phleboviruses in Anatolia, Turkey Ender Dinçer1†, Annika Brinkmann2†, Olcay Hekimoğlu3, Sabri Hacıoğlu4, Katalin Földes4, Zeynep Karapınar5, Pelin Fatoş Polat6, Bekir Oğuz5, Özlem Orunç Kılınç7, Peter Hagedorn2, Nurdan Özer3, Aykut Özkul4, Andreas Nitsche2 and Koray Ergünay2,8* Abstract Background: Ticks are involved with the transmission of several viruses with significant health impact. As incidences of tick-borne viral infections are rising, several novel and divergent tick- associated viruses have recently been documented to exist and circulate worldwide. This study was performed as a cross-sectional screening for all major tick-borne viruses in several regions in Turkey. Next generation sequencing (NGS) was employed for virus genome characterization. Ticks were collected at 43 locations in 14 provinces across the Aegean, Thrace, Mediterranean, Black Sea, central, southern and eastern regions of Anatolia during 2014–2016. Following morphological identification, ticks were pooled and analysed via generic nucleic acid amplification of the viruses belonging to the genera Flavivirus, Nairovirus and Phlebovirus of the families Flaviviridae and Bunyaviridae, followed by sequencing and NGS in selected specimens. Results: A total of 814 specimens, comprising 13 tick species, were collected and evaluated in 187 pools. Nairovirus and phlebovirus assays were positive in 6 (3.2%) and 48 (25.6%) pools. All nairovirus sequences were closely-related to the Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) strain AP92 and formed a phylogenetically distinct cluster among related strains. -

Joint Statement on Insect Repellents by EPA And

Joint Statement on Insect Repellents from the Environmental Protection Agency and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention July 17, 2014 The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are recommending that the public use insect repellents and take other precautions to avoid biting insects that carry serious diseases. The incidence of these diseases is on the rise. This joint statement discusses diseases that are transmitted by ticks and mosquitoes, the role of government in vector control and disease prevention, the history of repellents, how to use repellents as part of an integrated control program, and how to select and use a repellent. Introduction and Purpose CDC and EPA developed this joint statement to promote awareness of repellents and to highlight the effectiveness of repellents in preventing mosquito and tick bites. The agencies believe that promoting the use of repellents may reduce the impact of diseases and nuisance effects caused by these pests. Vector-borne diseases, such as those transmitted by mosquitoes and ticks, are among the world's leading causes of illness and death today. A wide variety of arthropods, including mosquitoes, ticks, fleas, black flies, sand flies, horse flies, stable flies, kissing bugs, lice and mites, feed on human blood. Among these, mosquitoes and ticks transmit some of the most serious vector- borne diseases both globally and within the United States. Diseases Transmitted by Mosquitoes and Ticks Mosquito-transmitted West Nile virus caused over 36,000 disease cases and 1,500 deaths in the United States between 1999 and 2012 (CDC, 2012). Mosquitoes also transmit other viruses that cause severe disease in the United States, including La Crosse encephalitis, eastern equine encephalitis and dengue. -

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus)

TABLE OF CONTENTS AFRICAN TICK BITE FEVER .........................................................................................3 AMEBIASIS .....................................................................................................................4 ANTHRAX .......................................................................................................................5 ASEPTIC MENINGITIS ...................................................................................................6 BACTERIAL MENINGITIS, OTHER ................................................................................7 BOTULISM, FOODBORNE .............................................................................................8 BOTULISM, INFANT .......................................................................................................9 BOTULISM, WOUND .................................................................................................... 10 BOTULISM, OTHER ...................................................................................................... 11 BRUCELLOSIS ............................................................................................................. 12 CAMPYLOBACTERIOSIS ............................................................................................. 13 CHANCROID ................................................................................................................. 14 CHLAMYDIA TRACHOMATIS INFECTION ................................................................. -

Summer Safety Guide C L I N T O N C O U N T Y H E a L T H D E P a R T M E N T

SUMMER SAFETY GUIDE C L I N T O N C O U N T Y H E A L T H D E P A R T M E N T S U M M E R 2 0 1 7 WHAT'S INSIDE... 2 7 W H A T ' S B I T I N G Y O U ? P R O T E C T Y O U R H O M E 3 8-9 M O S Q U I T O E S A N I M A L S A N D R A B I E S 4-5 10 T I C K S A N D L Y M E D I S E A S E B E D B U G S 6 11-12 P R O T E C T Y O U R S E L F S U N A N D W A T E R S A F E T Y WHAT'S BITING YOU? P R E V E N T I O N I S Y O U R B E S T D E F E N S E SUMMER HAS ARRIVED! THAT Mosquitoes West Nile virus (WNV) and Eastern MEANS SUN AND FUN, BUT IT equine encephalitis (EEE) are the most common diseases transmitted IS ALSO THE TIME OF YEAR Animals by local mosquitoes. There are no Wildlife is part of the beauty of our WHEN PEOPLE ARE MOST human vaccines for these diseases, Adirondack region, but animals are but there are simple steps you can best viewed from afar. -

Outbreak of Powassan Encephalitis Maine and Vermont, 1999-2001

FROM THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION nal fluid (CSF) contained 40 white blood Her clinical examination showed agita- Outbreak of cells (WBCs)/mm3 (normal: Ͻ4/mm3) tion without confusion, ataxia, bilat- (87% lymphocytes) with elevated pro- eral lateral gaze palsy, and dysarthria. Powassan tein (96 mg/dL; normal: 20-50 mg/dL). CSF contained 148 WBCs/mm3 (46% Encephalitis— Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) neutrophils, 40% lymphocytes). Dur- revealed parietal changes consistent with ing hospitalization, she developed al- Maine and Vermont, microvascular ischemia or demyelinat- tered mental status, generalized muscle 1999-2001 ing disease. No causes for his apparent weakness, and complete ophthalmople- stroke were found. After 22 days of hos- gia. An electroencephalogram (EEG) in- MMWR. 2001;50:761-764 pitalization, he was discharged to a reha- dicated diffuse encephalitis, and a MRI bilitation facility. Nearly 3 months after showed bilateral temporal lobe abnor- POWASSAN (POW) VIRUS, A NORTH symptom onset, he remains in the facil- malities consistent with microvascular American tickborne flavivirus related to ity and is unable to move his left arm or ischemia or demyelinating disease. Af- the Eastern Hemisphere’s tickborne en- leg. Serum specimens and CSF col- ter 13 days, she was transferred to a re- cephalitis viruses,1 was first isolated from lected 3 days after hospitalization habilitation facility where she re- a patient with encephalitis in 1958.1,2 revealed POW virus-specific IgM; neu- mained for 2 months. Nine months after During 1958-1998, 27 human POW en- tralizing antibody (1:640 titer) also was onset of symptoms, she was walking and cephalitis cases were reported from found in serum specimens. -

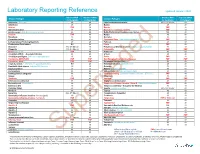

Laboratory Reporting Reference Updated January 2020

Laboratory Reporting Reference Updated January 2020 Report to MOH Report to CMOH Report to MOH Report to CMOH Disease / Pathogen Disease / Pathogen (or Designate) (or Designate) (or Designate) (or Designate) Aeromonas (Stool only) 48 48 Lymphogranuloma Venereum 48 to STI Director 48 Amoebiasis 48 48 Malaria 48 48 Anthrax FMP 48 Measles FMP 48 Arboviral Infections1 48 48 Meningococcal Disease, Invasive FMP 48 Bacillus cereus (Only stool or implicated food) 48 48 Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus N/A 48 Botulism FMP 48 Mumps 48 48 Brucellosis 48 48 Norovirus 48 48 Campylobacteriosis 48 48 Paratyphoid Fever (Salmonella paratyphi A, B or C) FMP 48 Carbapenemase-Producing Organisms 48 48 Pertussis 48 48 Cerebrospinal Fluid Isolates N/A 48 Plague FMP 48 Chancroid 48 to STI Director 48 Pneumococcal Disease, Invasive (Streptococcus pneumoniae) 48 48 Chlamydia 48 to STI Director 48 Poliomyelitis FMP FMP Cholera (O1, O139) FMP 48 Psittacosis 48 48 Clostridium difficile – Associated Infection 48 48 Q fever 48 48 Clostridium perfringens (Only stool or implicated food) 48 48 Rabies FMP 48 Coronavirus, MERS/SARS FMP FMP Rare/Emerging Communicable Diseases2 FMP FMP Coronavirus, Novel FMP FMP Respiratory Syncytial Virus 48 48 Corynebacterium (C. Ulcerans or C. pseudotuberculosis) N/A 48 Rickettsial Infections (Spotted Fevers) 48 48 Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (Includes 14-3-3 protein) 48 48 Rotavirus 48 48 Cryptosporidiosis 48 48 Rubella (Includes congenital) 48 48 Cyclosporiasis 48 48 Salmonellosis (Excludes paratyphi & typhi) 48 48 Cytomegalovirus, -

The Ecology of New Constituents of the Tick Virome and Their Relevance to Public Health

viruses Review The Ecology of New Constituents of the Tick Virome and Their Relevance to Public Health Kurt J. Vandegrift 1 and Amit Kapoor 2,3,* 1 The Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics, Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA; [email protected] 2 Center for Vaccines and Immunity, Research Institute at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, OH 43205, USA 3 Department of Pediatrics, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43205, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 21 March 2019; Accepted: 29 May 2019; Published: 7 June 2019 Abstract: Ticks are vectors of several pathogens that can be transmitted to humans and their geographic ranges are expanding. The exposure of ticks to new hosts in a rapidly changing environment is likely to further increase the prevalence and diversity of tick-borne diseases. Although ticks are known to transmit bacteria and viruses, most studies of tick-borne disease have focused upon Lyme disease, which is caused by infection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Until recently, ticks were considered as the vectors of a few viruses that can infect humans and animals, such as Powassan, Tick-Borne Encephalitis and Crimean–Congo hemorrhagic fever viruses. Interestingly, however, several new studies undertaken to reveal the etiology of unknown human febrile illnesses, or to describe the virome of ticks collected in different countries, have uncovered a plethora of novel viruses in ticks. Here, we compared the virome compositions of ticks from different countries and our analysis indicates that the global tick virome is dominated by RNA viruses. Comparative phylogenetic analyses of tick viruses from these different countries reveals distinct geographical clustering of the new tick viruses. -

Powassan Virus and Deer Tick Virus Most Tick-Borne Diseases, Such As Lyme, Are Caused by Bacteria

Powassan Virus and Deer Tick Virus Most tick-borne diseases, such as Lyme, are caused by bacteria. However, with a recent case in New Jersey and discovery in Connecticut blacklegged (deer) ticks, Powassan virus (POWV) has recently come to public attention. Approximately 75 cases of Powassan virus disease were reported in the United States over the past 12 years (103 since 1958) mostly from the Northeast and Great Lakes regions and incidence appears to be increasing. 23 human cases of illness occurred in NY from 1971 to 2016, primarily from the lower Hudson Valley area. Although some people infected with POW do not develop symptoms, it can cause encephalitis (inflammation of the brain) and meningitis (inflammation of the membranes that surround the brain and spinal cord). Other symptoms can include fever, headache, vomiting, weakness, confusion, drowsiness, lethargy, some paralysis, disorientation, loss of coordination, speech difficulties, seizures and memory loss. Long-term neurologic problems may occur and about 10% of cases are fatal. There is no specific treatment, but people with severe POW virus illnesses often need to be hospitalized to receive respiratory support, intravenous fluids, or medications to reduce swelling in the brain. Powassan virus was first identified in 1958 from a young boy in Powassan, Ontario who eventually died from the disease. Related to the West Nile Virus, in North America studies so far suggest POWV is a complex of viruses with two genetic ‘lineages’ including the initial (1958) LB strain and others found in Canada and New York State (POWV, Lineage I), and a second sometimes referred to as ‘deer tick virus’ (DTV, Lineage II), found in animals in the eastern and upper mid-west US and in humans. -

Powassan Virus Infection Disease Fact Sheet Series

WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH SERVICES P- 00355 (06/12) Division of Public Health Page 1 of 2 Powassan virus infection Disease Fact Sheet Series What is Powassan virus infection? Powassan virus (POWV) infection is a rare tickborne viral infection occurring in Wisconsin and other northern regions of North America. POWV infection is caused by an arbovirus (similar to the mosquito-borne West Nile virus) but it is transmitted to humans by the bite of an infected tick instead of a mosquito bite. The virus is named for Powassan, Ontario where it was first discovered. Eleven reported cases of POWV infection have been detected among Wisconsin residents during 2003 to 2011. At least 50 cases have been detected in the United States and Canada since 1958. How is Powassan virus spread? In Wisconsin, Ixodes scapularis (known as the blacklegged tick or deer tick) is capable of transmitting Powassan virus. In addition, several other tick species in North America can carry POWV, including other Ixodes species and Dermacentor andersoni. Where does Powassan virus infection occur? Powassan virus infection occurs mostly in northeastern and upper Midwestern states. In Wisconsin, cases have been detected in areas where there is a high risk of exposure to ticks. Who gets Powassan virus infection? Everyone is susceptible to Powassan virus, but people who spend time outdoors in tick-infested environments are at an increased risk of exposure. In the upper Midwest, the risk of tick exposure is highest from late spring through autumn. What are the symptoms of Powassan virus infection? Symptoms usually begin 7-14 days (range 8-34 days) following infection.