The YMCA and Chinese Laborers in World War I Europe1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEATURE the Forgotten Chinese Army in WWI Or Centuries, the Roots of Cheng Ling’S Populations Were Depleted

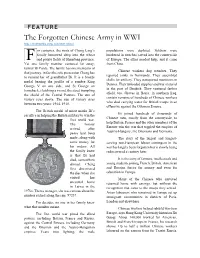

FEATURE The Forgotten Chinese Army in WWI http://multimedia.scmp.com/ww1-china/ or centuries, the roots of Cheng Ling’s populations were depleted. Soldiers were family burrowed deep into the wheat hunkered in trenches carved into the countryside F and potato fields of Shandong province. of Europe. The allies needed help, and it came Yet one family member ventured far away, from China. farmer Bi Cuide. The family has one memento of Chinese workers dug trenches. They that journey, in fact the sole possession Cheng has repaired tanks in Normandy. They assembled to remind her of grandfather Bi. It is a bronze shells for artillery. They transported munitions in medal bearing the profile of a sombre King Dannes. They unloaded supplies and war material George V on one side, and St George on in the port of Dunkirk. They ventured farther horseback, clutching a sword, the steed trampling afield, too. Graves in Basra, in southern Iraq, the shield of the Central Powers. The sun of contain remains of hundreds of Chinese workers victory rises above. The sun of victory rises who died carrying water for British troops in an between two years: 1914, 1918. offensive against the Ottoman Empire. The British medal of merit marks Bi’s Bi joined hundreds of thousands of sacrifice in helping the British military to win the Chinese men, mostly from the countryside, to first world war. help Britain, France and the other members of the The honour Entente win the war that toppled the empires of arrived after Austria-Hungary, the Ottomans and Germany. -

Trench Art and the Story of the Chinese Labour Corps in the Great

© James Gordon-Cumming 2020 All rights reserved. First published on the occasion of the exhibition Western Front – Eastern Promises Photography, trench art and iconography of the Chinese Labour Corps in the Great War hosted at The Brunei Gallery, SOAS University of London 1st October to 12th December 2020 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the permission of the publisher, James Gordon-Cumming. Front cover: Collecting stores for the long journey ahead © WJ Hawkings Collection, courtesy John de Lucy 2 Page Contents A New Republic ..................................................................................................................... 5 A War Like No Other ........................................................................................................... 7 The Chinese Solution ......................................................................................................... 9 The Journey to Europe .................................................................................................... 10 Across Canada ..................................................................................................................... 13 In support of the war machine ..................................................................................... 14 From Labourer to Engineer ........................................................................................... -

Synopsis for Wei Hai Wei, China, 1895-1949

Synopsis for Wei Hai Wei, China, 1895-1949 Mission: The postal history of Wei Hai Wei (WHW) and the island of Liu Kung Tau (LKT) for the period 1895-1949 is shown in this exhibit. Treatment: The exhibit starts with forerunners before the first Japanese Occupation in 1895-98 and ends at the formation of the Peoples Republic of China in October 1949. Grouped by different post offices, yet sometimes operating in parallel, and its markings and/or usages, the exhibit is presented in chronological order within the chapters. A chapter has been included under the British PO for the correspondence of the High Commissioner of WHW, Sir James Stewart Lockhart, with his daughter, plus other covers that were addressed to him. Chapters for special historical events, like the Boxer Rebellion, Chinese Labour Corps, both Japanese Occupation were also included, closing with the Communist taking over after WWII and ending with the formation of the Peoples Republic of China. This is a well-balanced exhibit covering every time period of WHW’s postal history and history, with in-depth examples shown for each period. The examples shown are selected for its rarity and its significance to postal history and history. Importance: In a political sense, WHW was the most important stronghold of Britain in Northern China and only second to Hong Kong for all of China. In a philatelic sense, its postal history included many “China’s one-of”. For example, the only Courier Post in China, the Chinese Labour Corps of WWI, the only Chinese city that has been invaded and occupied by the Japanese ‘twice’ in its history, i.e. -

China in the First World War: a Forgotten Army in Search of International Recognition

Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations: An International Journal Vol. 3, No. 3, Dec. 2017, pp. 1237-1269 __________________________________________________________ China in the First World War: A Forgotten Army in Search of International Recognition Roy Anthony Rogers* University of Malaya Nur Rafeeda Daut** Kansai Gaidai University Abstract The First World War (1914-1918) has been widely considered as a European conflict and a struggle for dominance among the European empires. However, it is important to note that non-European communities from various parts of the world such as the Chinese, Indians, Egyptians and Fijians also played significant roles in the war. This paper intends to provide an analysis of the involvement of China in the First World War. During the outbreak of the war in 1914, the newly established Republic of China (1912) encountered numerous problems and uncertainties. However, in 1917 the Republic of China entered the First World War, supporting the Allied Forces, with the aim of elevating its international position. This paper focuses on the treatment that China had received from the international community such as Britain, the United States, France and Japan after the war. Specifically, this paper 1237 1238 Roy Anthony Rogers and Nur Rafeeda Daut argues that the betrayal towards China by the Western powers during the Paris Peace Conference and the May Fourth Movement served as an intellectual turning point for China. It had triggered the radicalization of Chinese intellectual thoughts. In addition, China’s socialization during the Paris Peace Conference had been crucial to the conception of the West’s negative identity in the eyes of the Chinese that has remained in the minds of its future leaders. -

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Commonwealth War Graves Commission THE CHINESE LABOUR CORPS AT THE WESTERN FRONT y the Autumn of 1916 the demand for labour The Corps was to be non-combatant but part of to carry out vital logistical work behind the the British army and subject to military control. BAllied lines on the Western Front was They would carry out mainly manual tasks in the becoming critical. The catastrophic losses suffered rear areas and lines of communication, building by the British during the Battle of the Somme meant and repairing docks, roads, railways and airfields, that practically every able bodied serviceman was manning ports and railheads, stores and now needed for fighting and the government had ammunition depots, and working as stevedores to look to her Empire and beyond to meet the ever and crane operators unloading ships and trains. In growing need for skilled and unskilled labour to time, skilled mechanics would repair vehicles and support the army. Indian labour units had been at tanks and later, after the Armistice, the Corps work in France and Belgium since 1915. Other would undertake much of the dangerous and labour contingents would soon follow from South unpleasant work of battlefield clearance. Africa, Egypt and the Caribbean and in October 1916, following an example set by the French, the The call for volunteers was spread by public British approached the then neutral Chinese proclamation and by British missionaries in the government with a plan that would lead to the field. The rewards offered were tempting enough to formation of the Chinese Labour Corps. encourage thousands of men, mainly poor improvisation. -

Final Copy 2019 01 23 Winte

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Winterton, Melanie Title: Haptic Air-scapes, Materiality, and the First World War An Anthropological-Archaeological Perspective, 1914 - 2018 General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. HAPTIC AIR-SCAPES, MATERIALITY, AND THE FIRST WORLD WAR: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL-ARCHAEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE, 1914–2018 MELANIE R. WINTERTON UNIVERSITY OF BRISTOL DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND ARCHAEOLOGY A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Arts, Department of Anthropology and Archaeology May 2018 Word count: 78,185 ABSTRACT This research focuses on First World War aviators’ relationships with their aircraft from a sensorial anthropological-archaeological perspective. -

Civilian Specialists at War Britain’S Transport Experts and the First World War

Civilian Specialists at War Britain’s Transport Experts and the First World War CHRISTOPHER PHILLIPS Civilian Specialists at War Britain’s Transport Experts and the First World War New Historical Perspectives is a book series for early career scholars within the UK and the Republic of Ireland. Books in the series are overseen by an expert editorial board to ensure the highest standards of peer-reviewed scholarship. Commissioning and editing is undertaken by the Royal Historical Society, and the series is published under the imprint of the Institute of Historical Research by the University of London Press. The series is supported by the Economic History Society and the Past and Present Society. Series co-editors: Heather Shore (Manchester Metropolitan University) and Jane Winters (School of Advanced Study, University of London) Founding co-editors: Simon Newman (University of Glasgow) and Penny Summerfield (University of Manchester) New Historical Perspectives Editorial Board Charlotte Alston, Northumbria University David Andress, University of Portsmouth Philip Carter, Institute of Historical Research, University of London Ian Forrest, University of Oxford Leigh Gardner, London School of Economics Tim Harper, University of Cambridge Guy Rowlands, University of St Andrews Alec Ryrie, Durham University Richard Toye, University of Exeter Natalie Zacek, University of Manchester Civilian Specialists at War Britain’s Transport Experts and the First World War Christopher Phillips LONDON ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS Published in 2020 by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PRESS SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU © Christopher Phillips 2020 The author has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. -

Chinese Labour Corps – a Force Reference to These Men

Almost Forgotten As we commemorate the TIME TO REMEMBER centenary of the First World Despite there being over 40,000 War, almost forgotten stories First World War Memorials in The are emerging. The story of the Britian, not one includes any Chinese Labour Corps – a force reference to these men. Almost Chinese Labour Corps of 96,000 volunteers – is one forgotten, it is now time to such story. remember. 1916-1920 The contribution of these men Join us in our camaign for a has routinely been overlooked or national memorial to these Three weeks before the end of WWI the world’s largest painting opened relegated to a footnote in history. men. Visit our website or follow to the public in Paris. Called Panthéon de la Guerre, it was begun in us on Facebook or Twitter 1914, and depicted France victorious, surrounded by all her allies. But These men deserve better, and in 1917, with the painting almost complete, the United States entered our nation’s promise never to the war. forget should apply to them as to ww1clc any other. For the Americans to be included in the painting, the artists had no choice www.EnsuringWeRemember.org.uk but to paint over an existing scene. In what is to become an apt analogy A Startegc Partnership actively working with a diverse range of of their fete, the Chinese Labour Corps are painted out. But who were the organisations to inspire, to educate, and to ensure that the men of Chinese Labour Corps, and why were they in France? the Chinese Labour Corps are remembered once more. -

The Chinese Labour Corps on the Western Front: Management, Discipline, And

The Chinese Labour Corps on the Western Front: Management, Discipline, and Crime by Peter Burrows Canterbury Christ Church University Thesis submitted for the degree of MA by Research in History 2018 Contents Acknowledgements - 2 Abstract - 3 Introduction - 4 Chinese Labour in Context - 11 Britain - 11 China - 30 The ‘Children’ Lack Discipline - 38 Crime - 59 Meritorious Behaviour and Repatriation - 76 The Philosophy, Morality, and Legality of British Leadership - 86 Discussion: Management, Discipline & Crime - 98 Bibliography - 104 Primary Sources - 104 Secondary Sources - 110 Word Count - 29,956 1 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my supervisors for their time, guidance, and invaluable advice during the research and write up of this study. Their continued support and encouragement have made writing this dissertation a considerably easier task. I would also like to thank the University of Leeds’ Special Collections Library and the Imperial War Museum for permission to reproduce archival material for the purposes of this research. Finally, I wish to express my sincerest gratitude to my parents for their continual support and encouragement throughout my academic years, and during the completion of this dissertation. I would also like to thank my partner, Pinchi, for her unremitting patience, understanding, and reassurance while I completed this research. Without them, this work would not have been possible. Thank you. Author Peter Burrows 2 Abstract This dissertation examines the events surrounding the formation and deployment of the Chinese Labour Corps during the Great War. It covers the period from 1917 to 1922, during which Britain recruited around 100,000 Chinese labourers to offset its severe manpower shortages. -

The Chinese Labour Corps

Volume 13 | Issue 51 | Number 1 | Article ID 4411 | Dec 21, 2015 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Forgotten voices from the Great War: the Chinese Labour Corps Alex Calvo, Bao Qiaoni forgotten. While not supplying combat troops, China entered the First World War on the side of the Allies, furnishing much-needed labourers, 140,000 by conservative estimates and possibly more, who played an essential role on the Western Front and other theatres, taking responsibility for a wide range of tasks. Among others, unloading military supplies and handling ammunitions, building barracks and other military facilities, digging trenches, and even agriculture and forest management. While their essential contribution was recognized in British documents, both Paris and London saw them as a temporary expedient, to be ended as soon as the war was over. Furthermore, their deployment gave rise to all sorts of culture and language clashes, in addition to the dangers of travelling to Europe and surviving in close proximity to the battle field. However, beyond these travails, the Chinese Labour Corps left a significant legacy, with members seeing the world, experiencing other nations, and often becoming literate. More widely, despite being on the winning side, China's failure to secure any gains at Versailles prompted the May 4th Movement and can be seen as a key juncture in the long and winding road from empire to nation-state. It is an important reminder of the global nature of the Great War, whose impact Cap badge of the Chinese Labour Corps extended far from the battle field to all corners CLC personnel moving sacks of corn at Boulogne, on of the world. -

Xerox University Microfiims 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 73-23,922

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Paga(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

![Age-Dependence of the 1918 Pandemic G. Woo* [Presented to the Meeting of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, London, 17 September 2018]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9952/age-dependence-of-the-1918-pandemic-g-woo-presented-to-the-meeting-of-the-institute-and-faculty-of-actuaries-london-17-september-2018-4429952.webp)

Age-Dependence of the 1918 Pandemic G. Woo* [Presented to the Meeting of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, London, 17 September 2018]

British Actuarial Journal, Vol. 24, e3, pp. 1–16. © Institute and Faculty of Actuaries 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S1357321719000023 Age-dependence of the 1918 pandemic G. Woo* [Presented to the Meeting of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries, London, 17 September 2018] Abstract A well-known feature of the great H1N1 influenza pandemic of a century ago is that the highest mortality rate was amongst young adults. The general explanation has been that they died from an over-reaction of their active immune systems. This explanation has never been very satisfactory because teenagers also have very active immune systems. Recent virological research provides a new perspective, which is important for life and health insurers. There is now strong recent scientific evidence for the principle of antigenic imprinting, where the highest antibody response is against influenza virus strains from childhood. The peak ages of 1918 pandemic mortality correspond to a cohort exposed to the H3N8 1889–1890 Russian influenza pandemic. The vulnerability of an individual depends crucially on his or her exposure to influenza during their lifetime, especially childhood. Date of birth is thus a key indicator of pandemic vulnerability. An analysis of the implications is presented, with focus on those now in their fifties, who were exposed to the H3N2 1968 Hong Kong influenza. Keywords Influenza; Pandemic; 1918; Antigenic; Imprinting 1.