Levine CLC Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New China and Its Qiaowu: the Political Economy of Overseas Chinese Policy in the People’S Republic of China, 1949–1959

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science New China and its Qiaowu: The Political Economy of Overseas Chinese policy in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1959 Jin Li Lim A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2016. 2 Declaration: I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,700 words. 3 Abstract: This thesis examines qiaowu [Overseas Chinese affairs] policies during the PRC’s first decade, and it argues that the CCP-controlled party-state’s approach to the governance of the huaqiao [Overseas Chinese] and their affairs was fundamentally a political economy. This was at base, a function of perceived huaqiao economic utility, especially for what their remittances offered to China’s foreign reserves, and hence the party-state’s qiaowu approach was a political practice to secure that economic utility. -

FEATURE the Forgotten Chinese Army in WWI Or Centuries, the Roots of Cheng Ling’S Populations Were Depleted

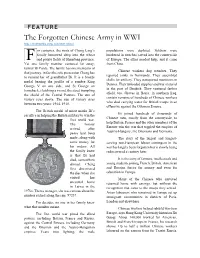

FEATURE The Forgotten Chinese Army in WWI http://multimedia.scmp.com/ww1-china/ or centuries, the roots of Cheng Ling’s populations were depleted. Soldiers were family burrowed deep into the wheat hunkered in trenches carved into the countryside F and potato fields of Shandong province. of Europe. The allies needed help, and it came Yet one family member ventured far away, from China. farmer Bi Cuide. The family has one memento of Chinese workers dug trenches. They that journey, in fact the sole possession Cheng has repaired tanks in Normandy. They assembled to remind her of grandfather Bi. It is a bronze shells for artillery. They transported munitions in medal bearing the profile of a sombre King Dannes. They unloaded supplies and war material George V on one side, and St George on in the port of Dunkirk. They ventured farther horseback, clutching a sword, the steed trampling afield, too. Graves in Basra, in southern Iraq, the shield of the Central Powers. The sun of contain remains of hundreds of Chinese workers victory rises above. The sun of victory rises who died carrying water for British troops in an between two years: 1914, 1918. offensive against the Ottoman Empire. The British medal of merit marks Bi’s Bi joined hundreds of thousands of sacrifice in helping the British military to win the Chinese men, mostly from the countryside, to first world war. help Britain, France and the other members of the The honour Entente win the war that toppled the empires of arrived after Austria-Hungary, the Ottomans and Germany. -

崑 山 科 技 大 學 應 用 英 語 系 Department of Applied English Kun Shan University

崑 山 科 技 大 學 應 用 英 語 系 Department of Applied English Kun Shan University National Parks in Taiwan 臺灣的國家公園 Instructor:Yang Chi 指導老師:楊奇 Wu Hsiu-Yueh 吳秀月 Ho Chen-Shan 何鎮山 Tsai Ming-Tien 蔡茗恬 Wang Hsuan-Chi 王萱琪 Cho Ming-Te 卓明德 Hsieh Chun-Yu 謝俊昱 中華民國九十四年四月 April, 2006 Catalogue Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................ 2 1.1 Research motivation ...................................................................................... 2 1.2 Research purpose ........................................................................................... 3 1.3 Research procedure ....................................................................................... 6 Chapter 2 Research Information ............................................. 8 2.1 Yangmingshan National Park ....................................................................... 8 2.2 Shei-Pa National Park ................................................................................. 12 2.3 Taroko National Park .................................................................................. 17 2.4 Yushan National Park .................................................................................. 20 2.5 Kenting National Park ................................................................................. 24 2.6 Kinmen National Park ................................................................................. 28 Chapter 3 Questionnarie ........................................................ 32 Chapter 4 Conclusion ............................................................ -

Archives in the People's Republic of China

American Archivist/Vol. 45, No. 4/Fall 1982 385 Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/45/4/385/2746939/aarc_45_4_24q7467764463454.pdf by guest on 25 September 2021 Archives in the People's Republic of China WILLIAM W. MOSS Introduction BETWEEN 19 APRIL AND 9 MAY 1982 Guangdong Provincial Archives in members of the Society of American Ar- Guangzhou.' In addition, six museums, chivists' study tour to the People's seven tombs and excavations, five parks Republic of China, including two Cana- and public gardens, eighteen historic dian colleagues from Alberta, traveled sites or buildings, and assorted other in- from Beijing (Peking), in the north to stitutions and enterprises were visited. Guangzhou in the south, visiting ar- The latter included a paper mill, a jade- chives and touring museums, historic carving factory, a silk embroidery in- sites, and other attractions in nine cities. stitute, a silk-weaving factory, a Seven archives were visited: the First cloisonne factory, a social welfare Historical Archives of China (Di Yi house, a normal school, a hospital, and Lishi Danganguan) and the Imperial an agricultural production brigade.2 Records Storehouse (Huang Shi Cheng) Such a three-week whirlwind tour of in Beijing; the Kong Family Archives China has its own rewards, and all (Confucian Archives) in Qufu; the Shan- members of the group derived their own dong Provincial Archives in Jinan; the pleasures from it. But the time is too Second Historical Archives of China (Di short, the subject too new, the cultural Er Lishi Danganguan) in Nanjing; the adjustments too great, and the language Shanghai Municipal Archives; and the barrier too formidable for more than 'Pinyin romanization of Chinese names is used throughout this article (except for the following cases: Chiang Kai-shek, Sun Yat-sen, Yangtze, and Kuomintang), even though we discovered that the Chinese themselves are not meticulously consistent in its use. -

Trench Art and the Story of the Chinese Labour Corps in the Great

© James Gordon-Cumming 2020 All rights reserved. First published on the occasion of the exhibition Western Front – Eastern Promises Photography, trench art and iconography of the Chinese Labour Corps in the Great War hosted at The Brunei Gallery, SOAS University of London 1st October to 12th December 2020 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the permission of the publisher, James Gordon-Cumming. Front cover: Collecting stores for the long journey ahead © WJ Hawkings Collection, courtesy John de Lucy 2 Page Contents A New Republic ..................................................................................................................... 5 A War Like No Other ........................................................................................................... 7 The Chinese Solution ......................................................................................................... 9 The Journey to Europe .................................................................................................... 10 Across Canada ..................................................................................................................... 13 In support of the war machine ..................................................................................... 14 From Labourer to Engineer ........................................................................................... -

Meet the Most Friendly People and Enjoy the Local Hospitality. a Paradise for Food Lovers

Meet the most friendly people and enjoy the local hospitality. A paradise for food lovers Fall in love with the beauty of naturenature andd architecturee in Taiwan.aiwwanwan Map of Taiwan Wulaiulaai Danshui 淡水 Yangmingshan National Park Yehliu 野柳 Jiufen 九份 烏來來 陽明山國家公園 Keelung Taipei 基隆 台北 Taoyuan 桃園 New Taipei City 新北市 Hsinchu 新竹 Hehuanshan Gaomeiomei Wetlands 合歡山 高美濕地美濕地 Yilan 宜蘭 Miaoli 苗栗 Taichung 台中 Taroko National Park 太魯閣國家公園 Nantou 南投 Hualien 花蓮 Changhua 彰化 Sunn MoonMo Lake 日月潭月潭 Yunlin 雲林 Chiayi 嘉義 Thehe PenghuPeP Islands 澎湖 Tainan 台南 Kaohsiung 高雄 Yushan National Park Taitung 台東 玉山國家公園 Green Island 綠島 Pingtung 屏東 Huatung Valley 花東縱谷 Alishanishan National Scenic Orchid Island 蘭嶼 Areaea 阿里山國家風景區阿里 ➔ Kenting National Park 墾丁國家公園 Fortrt AnpingAnp 安平古堡平古堡 Lotus Lake 蓮池潭 Map of Taiwan Unit 01 *HRJUDSK\ Word Bank separate v. range n. Taiwan Blue Magpie soak v. measure v. in length encounter v. factory n. roughly adv. landslide n. active a. plenty of make up (of) poisonous a. extinct a. concentrate v. glimpse n. dormant a. certain a. Reading Passage 01 Taiwan is an island in East Asia that lies between the Philippines and Japan. It is very close to mainland China. Taiwan and China are separated by Japan the Taiwan Strait, which is only 220 China kilometers at its widest point and 130 Taiwan kilometers at its narrowest point. Taiwan measures about 36,000 square kilometers, Philippines which is roughly the same size as the Netherlands. It is made up of one main island and several other smaller islands, such as the Penghu Islands, Orchid Island, and Green Island. -

Synopsis for Wei Hai Wei, China, 1895-1949

Synopsis for Wei Hai Wei, China, 1895-1949 Mission: The postal history of Wei Hai Wei (WHW) and the island of Liu Kung Tau (LKT) for the period 1895-1949 is shown in this exhibit. Treatment: The exhibit starts with forerunners before the first Japanese Occupation in 1895-98 and ends at the formation of the Peoples Republic of China in October 1949. Grouped by different post offices, yet sometimes operating in parallel, and its markings and/or usages, the exhibit is presented in chronological order within the chapters. A chapter has been included under the British PO for the correspondence of the High Commissioner of WHW, Sir James Stewart Lockhart, with his daughter, plus other covers that were addressed to him. Chapters for special historical events, like the Boxer Rebellion, Chinese Labour Corps, both Japanese Occupation were also included, closing with the Communist taking over after WWII and ending with the formation of the Peoples Republic of China. This is a well-balanced exhibit covering every time period of WHW’s postal history and history, with in-depth examples shown for each period. The examples shown are selected for its rarity and its significance to postal history and history. Importance: In a political sense, WHW was the most important stronghold of Britain in Northern China and only second to Hong Kong for all of China. In a philatelic sense, its postal history included many “China’s one-of”. For example, the only Courier Post in China, the Chinese Labour Corps of WWI, the only Chinese city that has been invaded and occupied by the Japanese ‘twice’ in its history, i.e. -

9789814779746 (.Pdf)

CU L TUR For ReviewE only SHOCK CULTURE SHOCK! ! A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette TAIWAN The CultureShock! series is a dynamic and indispensable range of guides for those travellers who are looking to truly understand the countries they are visiting. Each title explains the customs, traditions, social and business etiquette in a lively and informative style. CultureShock! authors, all of whom have experienced the joys and pitfalls of cultural adaptation, are ideally placed to provide warm and informative advice to those who seek to integrate seamlessly into diverse cultures. Each CultureShock! book contains: • insights into local culture and traditions • advice on adapting into the local environment • linguistic help, and most importantly • how to get the most out of your travel experience CultureShock! Taiwan is full of helpful advice on what to expect when you first arrive in the country and how to enjoy your stay. This book shares insights into understanding Taiwanese traditions and values as well as CULTURE the lifestyles of the people and how to relate to them as friends and in SHOCK business. Learn more about the main motivations and attitudes that ! shape their culture and what you should do in order to build more lasting A Survival Guide to Customs and Etiquette relationships with them. Also included is useful information on finding a home, understanding the language, handling tricky business negotiations and exploring the delicious (and sometimes shocking) Taiwanese cuisine. CultureShock! Taiwan will provide you with -

Changing Faces in the Chinese Communist Revolution

CHANGING FACES IN THE CHINESE COMMUNIST REVOLUTION: PARTY MEMBERS AND ORGANIZATION BUILDING IN TWO JIAODONG COUNTIES 1928-1948. by YANG WU A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) December 2013 © Yang Wu 2013 Abstract The revolution of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from the 1920s to the late 1940s was a defining moment in China’s modern history. It dramatically restructured Chinese society and created an authoritarian state that remains the most important player in shaping the country’s development today. Scholars writing to explain the success of the revolution began with trying to uncover factors outside of the party that helped to bring it to power, but have increasingly emphasized the ability of party organizations and their members to direct society to follow the CCP’s agendas as the decisive factor behind the party’s victory. Despite highlighting the role played by CCP members and the larger party organization in the success of the revolution studies have done little to examine how ordinary individuals got involved in the CCP at different stages and locations. Nor have scholars analyzed in depth the process of how the CCP molded millions of mostly rural people who joined it from the 1920s to the 40s into a disciplined force to seize control of China. Through a study of the CCP’s revolution in two counties of Jiaodong, a region of Shandong province in eastern China during this period my dissertation explores this process by focusing on their local party members. -

Local Information

Local information Wikimania 2007 Taipei :: a Globe in Accord English • Deutsch • Français • Italiano • 荳袿ᣩ • Nederlands • Norsk (bokmål) • Português • Ο錮"(顔覓/ヮ翁) • Help translation Taipei is the capital of Republic of China, and is the largest city of Taiwan. It is the political, commercial, media, educational and pop cultural center of Taiwan. According to the ranking by Freedom House, Taiwan enjoys the most free government in Asia in 2006. Taiwan is rich in Chinese culture. The National Palace Museum in Taipei holds world's largest collection of Chinese artifacts, artworks and imperial archives. Because of these characteristics, many public institutions and private companies had set their headquarters in Taipei, making Taipei one of the most developed cities in Asia. Well developed in commercial, tourism and infrastructure, combined with a low consumers index, Taipei is a unique city of the world. You could find more information from the following three sections: Local Information Health, Regulations Main Units of General Weather safety, and Financial and Electricity Embassies Time Communications Page measurement Conversation Accessibility Customs Index 1. Weather - Local weather information. 2. Health and safety - Information regarding your health and safety◇where to find medical help. 3. Financial - Financial information like banks and ATMs. 4. Regulations and Customs - Regulations and customs information to help your trip. 5. Units of measurement - Units of measurement used by local people. 6. Electricity - Infromation regarding voltage. 7. Embassies - Information of embassies in Taiwan. 8. Time - Time zone, business hours, etc. 9. Communications - Information regarding making phone calls and get internet services. 10. General Conversation - General conversation tips. 1. -

China in the First World War: a Forgotten Army in Search of International Recognition

Contemporary Chinese Political Economy and Strategic Relations: An International Journal Vol. 3, No. 3, Dec. 2017, pp. 1237-1269 __________________________________________________________ China in the First World War: A Forgotten Army in Search of International Recognition Roy Anthony Rogers* University of Malaya Nur Rafeeda Daut** Kansai Gaidai University Abstract The First World War (1914-1918) has been widely considered as a European conflict and a struggle for dominance among the European empires. However, it is important to note that non-European communities from various parts of the world such as the Chinese, Indians, Egyptians and Fijians also played significant roles in the war. This paper intends to provide an analysis of the involvement of China in the First World War. During the outbreak of the war in 1914, the newly established Republic of China (1912) encountered numerous problems and uncertainties. However, in 1917 the Republic of China entered the First World War, supporting the Allied Forces, with the aim of elevating its international position. This paper focuses on the treatment that China had received from the international community such as Britain, the United States, France and Japan after the war. Specifically, this paper 1237 1238 Roy Anthony Rogers and Nur Rafeeda Daut argues that the betrayal towards China by the Western powers during the Paris Peace Conference and the May Fourth Movement served as an intellectual turning point for China. It had triggered the radicalization of Chinese intellectual thoughts. In addition, China’s socialization during the Paris Peace Conference had been crucial to the conception of the West’s negative identity in the eyes of the Chinese that has remained in the minds of its future leaders. -

3. Study Chinese in Beautiful Taiwan

TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 10 Reasons for Learning Chinese in Taiwan 04 Getting to Know Taiwan 06 More about Taiwan History Climate Geography Culture Ni Hao Cuisine 08 Applying to Learn Chinese in Taiwan Step-by-Step Procedures 09 Scholarships 10 Living in Taiwan Accommodations Services Work Transportation 12 Test of Chinese as a Foreign Language (TOCFL) Organisation Introduction Test Introduction Target Test Taker Test Content Test Format Purpose of the TOCFL TOCFL Test Overseas Contact SC-TOP 14 Chinese Learning Centers in Taiwan - North 34 Chinese Learning Centers in Taiwan - Central 41 Chinese Learning Centers in Taiwan - South 53 Chinese Learning Centers in Taiwan - East 54 International Students in Taiwan 56 Courses at Chinese Learning Centers 60 Useful Links 學 8. High Standard of Living 華 10 REASONS FOR Taiwan’s infrastructure is advanced, and its law-enforcement and transportation, communication, medical and public health systems are 語 LEARNING CHINESE excellent. In Taiwan, foreign students live and study in safety and comfort. 9. Test of Chinese as Foreign IN TAIWAN Language (TOCFL) The Test of Chinese as a Foreign Language (TOCFL), is given to international students to assess their Mandarin Chinese listening 1. A Perfect Place to Learn Chinese and reading comprehension. See p.12-13 for more information) Mandarin Chinese is the official language of Taiwan. The most effective way to learn Mandarin is to study traditional Chinese characters in the modern, Mandarin speaking society of Taiwan. 10. Work While You Study While learning Chinese in Taiwan, students may be able to work part-time. Students will gain experience and a sense of accomplishment LEARNING CHINESE IN TAIWAN 2.