Making Big Cases Small & Small Cases Disappear

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Release Lists English (14-Apr-2021)

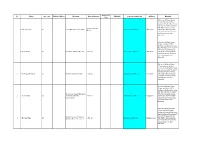

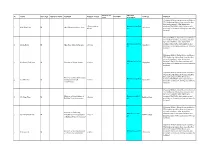

Section of No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. 1-Feb-21 and 10- 1 Salai Lian Luai M Chief Minister of Chin State Released on 26 Feb 21 Chin State The NLD’s chief ministers Feb-21 and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. 2 (U) Zo Bawi M Chin State Hluttaw Speaker 1-Feb-21 Released on 26 Feb 21 Chin State The NLD’s chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. 3 (U) Naing Thet Lwin M Minister of Ethnic Affairs 1-Feb-21 Released on 23 Feb 21 Naypyitaw The NLD’s chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Minister of Natural Resources Win Myint were detained. 4 (U) Ohn Win M and Environmental 1-Feb-21 Released on 23 Feb 21 Naypyitaw The NLD’s chief ministers Conservation and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. -

President Meets Chief Justice and Supreme Court Judges

DEVELOPMENT OF ELEPHANT CONSERVATION-BASED TOURISM P-2 (NATIONAL) NATIONAL NATIONAL President U Win Myint meets with Union Minister for Health and Sports Anti-Corruption Commission Dr. Myint Htwe attends Signing Ceremony P-3 P-3 Vol. IV, No. 360, 12th Waning of Tagu 1379 ME www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Thursday, 12 April 2018 Mro ethnic villagers receive new houses RAKHINE STATE authorities handed over new houses to Mro ethnic people at the Thit- tonna Gwason Village-tract in Maungtaw Township yes- terday. The 86 houses were funded by the Ayeyawady Region Government and Mandalay Region Govern- ment, and handed over to Mro ethnic families from Karuchaung, Myatkhaung- taung, Panchaung and Inn Chaung villages from Thit- President U Win Myint, centre, meeting with Union Chief Justice U Htun Htun Oo, sixth from left, and Supreme Court Judges yesterday. PHOTO: MNA tonna Gwason Village-tract in Maungtaw Township. The authorities also de- livered a set of solar panels President meets Chief Justice and a family kit, each donated by the Ministry of Industry to Mro ethnic families who lost their homes in terrorist and Supreme Court judges attacks last year. “We are delighted to stay in the new house in the plains RESIDENT U Win The President further said en the sector. He noted that the management of court evidence, area, instead of in the hills Myint met with Union there needs to be stricter reg- Chief Justice has the responsi- challenges faced by courts, re- where we used to live,” said Chief Justice U Htun ulations in maintaining court bility to strengthen the entire sponsibilities taken by the Su- U Aung Phaw, a Mro ethnic PHtun Oo and Supreme evidence, as loss and damage country’s judiciary sector and to preme Court of the Union, the man. -

WLB Herstory During the 2007-8 Term

WWomen’somen’s LLeagueeague ooff BBurmaurma The Women’s League of Burma (WLB) is an umbrella organisation comprising 12 women’s organisations of diff erent ethnic backgrounds from Burma. WLB was founded on 9th December, 1999. Its mission is to work for women’s empowerment and advancement of the status of women, and to work for the increased participation of women in all spheres of society in the democracy movement, and in peace and national reconciliation processes through capacity building, advocacy, research and documentation. Aims • To work for the empowerment and advancement of the status of women • To work for the rights of women and gender equality • To work for the Elimination of all forms of discrimination and violence against women • To work for the increased participation of women in every level of decision making in all spheres of society • To participate eff ectively in the movement for peace, democracy and national reconciliation TTableable ooff CContentsontents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 The Context ................................................................................................................ 3 A Chronology of Events leading to the Founding of the League ........................... 8 1992-1997: New Women’s Groups, New Challenges for Women........................ 8 1998-1999: Organizing to Form an Alliance ....................................................... 15 Refl ecting on the Founding of the Alliance ...................................................... -

Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006

Burma Page 1 of 24 2005 Human Rights Report Released | Daily Press Briefing | Other News... Burma Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2005 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 8, 2006 Since 1962, Burma, with an estimated population of more than 52 million, has been ruled by a succession of highly authoritarian military regimes dominated by the majority Burman ethnic group. The current controlling military regime, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), led by Senior General Than Shwe, is the country's de facto government, with subordinate Peace and Development Councils ruling by decree at the division, state, city, township, ward, and village levels. In 1990 prodemocracy parties won more than 80 percent of the seats in a generally free and fair parliamentary election, but the junta refused to recognize the results. Twice during the year, the SPDC convened the National Convention (NC) as part of its purported "Seven-Step Road Map to Democracy." The NC, designed to produce a new constitution, excluded the largest opposition parties and did not allow free debate. The military government totally controlled the country's armed forces, excluding a few active insurgent groups. The government's human rights record worsened during the year, and the government continued to commit numerous serious abuses. The following human rights abuses were reported: abridgement of the right to change the government extrajudicial killings, including custodial deaths disappearances rape, torture, and beatings of -

'Threats to Our Existence'

Threats to Our Existence: Persecution of Ethnic Chin Christians in Burma Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on Threats to Our Existence: Persecution of Ethnic Chin Christians in Burma September, 2012 © Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on 2 Montavista Avenue Nepean ON K2J 2L3 Canada www.chro.ca Photos © CHRO Front cover: Chin ChrisƟ ans praying over a cross they were ordered to destroy by the Chin State authoriƟ es, Mindat township, July 2010. Back cover: Chin ChrisƟ an revival group in Kanpetlet township, May 2010. Design & PrinƟ ng: Wanida Press, Thailand ISBN: 978-616-305-461-6 Threats to Our Existence: PersecuƟ on of ethnic Chin ChrisƟ ans in Burma i Contents CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... i Figures and appendices .................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ....................................................................................................................... v DedicaƟ on ...................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ viii About the Chin Human Rights OrganizaƟ on................................................................... ix RaƟ onale and methodology ........................................................................................... ix Foreword ....................................................................................................................... -

Release Lists English (4-Jun-2021)

Section of Current No Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Plaintiff Address Remark Law Condition Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were 1-Feb-21 and 10- Released on 26 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 1 Salai Lian Luai M Chief Minister of Chin State Chin State Feb-21 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Released on 26 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 2 (U) Zo Bawi M Chin State Hluttaw Speaker 1-Feb-21 Chin State 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Released on 23 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 3 (U) Naing Thet Lwin M Minister of Ethnic Affairs 1-Feb-21 Naypyitaw 21 ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Minister of Natural Resources Released on 23 Feb detained. The NLD’s chief ministers and 4 (U) Ohn Win M and Environmental 1-Feb-21 Naypyitaw 21 ministers in the states and regions were also Conservation detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were Minister of Social Affairs of Released on 2 Feb detained. -

Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 23 | September 2020 Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election KEY POINTS • The 2020 general election is scheduled to take place at a critical moment in Myanmar’s transition from half a century under military rule. The advent of the National League for Democracy to government office in March 2016 was greeted by all the country’s peoples as the opportunity to bring about real change. But since this time, the ethnic peace process has faltered, constitutional reform has not started, and conflict has escalated in several parts of the country, becoming emergencies of grave international concern. • Covid-19 represents a new – and serious – challenge to the conduct of free and fair elections. Postponements cannot be ruled out. But the spread of the pandemic is not expected to have a significant impact on the election outcome as long as it goes ahead within constitutionally-appointed times. The NLD is still widely predicted to win, albeit on reduced scale. Questions, however, will remain about the credibility of the polls during a time of unprecedented restrictions and health crisis. • There are three main reasons to expect NLD victory. Under the country’s complex political system, the mainstream party among the ethnic Bamar majority always win the polls. In the population at large, a victory for the NLD is regarded as the most likely way to prevent a return to military government. The Covid-19 crisis and campaign restrictions hand all the political advantages to the NLD and incumbent authorities. ideas into movement • To improve election performance, ethnic nationality parties are introducing a number of new measures, including “party mergers” and “no-compete” agreements. -

Appointment of Union Ministers ( Order 3/2016 )

Appointment of Union Ministers ( Order 3/2016 ) http://www.president-office.gov.mm/en/?q=print/6168 Published on Myanmar President Office (http://www.president-office.gov.mm/en) Home > Appointment of Union Ministers ( Order 3/2016 ) Appointment of Union Ministers ( Order 3/2016 ) Republic of the Union of Myanmar President’s Office Order 3/2016 7th Waning of Tabaung, 1377 ME (Wednesday, 30 March, 2016) Appointment of Union Ministers In accordance with the provisions stated in article 232 of the Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and article 12 of the Union Government Law, the following persons have been appointed as Union Ministers. No. Union Minister Ministry 1. Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ministry of President’s Office Ministry of Electric Power and Energy Ministry of Education 2. Lt-Gen Kyaw Swe Ministry of Home Affairs 3. Lt-Gen Sein Win Ministry of Defence 4. Lt-Gen Ye Aung Ministry of Border Affairs 5. Dr Pe Myint Ministry of Information 1 sur 3 31/05/2016 21:09 Appointment of Union Ministers ( Order 3/2016 ) http://www.president-office.gov.mm/en/?q=print/6168 6. Thura U Aung Ko Ministry of Religious Affairs and Culture 7. Dr Aung Thu Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation 8. U Thant Sin Maung Ministry of Transport and Communications Ministry of Natural Resources and 9. U Ohn Win Environmental Conservation 10. U Thein Swe Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population 11. U Khin Maung Cho Ministry of Industry 12. Dr Than Myint Ministry of Commerce 13. -

And the Lahu Democratic Union ( LDU )

The signing ceremony of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement, which was signed by the New Mon State Party ( NMSP ) and the Lahu Democratic Union ( LDU ) The New Mon State Party ( NMSP ) and the Lahu Democratic Union ( LDU ) signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement at the Myanmar International Convention Center -II in Nay Pyi Taw on 13 February 2018, an event that State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi described as “only the beginning” of a long quest for peace which was published by Myanmar State Counsellor Office. Myanmar Embassy in Tokyo Two ethnic armed groups sign ceasefire agreement in Nay Pyi Taw Nay Pyi Taw, Feb 13 The New Mon State Party (NMSP) and the Lahu Democratic Union (LDU) signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement at the Myanmar International Convention Center -II in Nay Pyi Taw yesterday, an event that State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi described as “only the beginning” of a long quest for peace. “The NCA is not the end of the peace process. The NCA is the beginning of the peace process”, the State Counsellor said. “The beginning of political dialogues, the beginning of reduction of armed conflicts; it is the beginning of the political process that will result from the resolution of political problems through negotiations, discussions and the joint search for solutions”. Myanmar gained independence from Great Britain 71 years ago, but the country has endured fighting between ethnic armed groups and government troops for decades. Dr. Tin Myo Win, Chairman of the Union Peace Commission (UPC) spoke first at yesterday’s ceremony, noting that it was a long process that resulted in yesterday’s signing of the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA). -

Deciphering Myanmar Peace Process a Reference Guide 2016

Deciphering Myanmar’s Peace Process: A Reference Guide 2016 www.bnionline.net www.mmpeacemonitor.org Deciphering Myanmar’s Peace Process: A Reference Guide 2016 Written and Edited by Burma News International Layout/Design by Saw Wanna(Z.H) Previous series: 2013, 2014 and 2015 Latest and 2016 series: January 2017 Printer: Prackhakorn Business Co.,ltd Copyright reserved by Burma News International Published by Burma News International P.O Box 7, Talad Kamtieng PO Chiang Mai, 50304, Thailand E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.mmpeacemonitor.org Twitter: http://twitter.com/mmpeacemonitor Facebook: http:// www.facebook.com/mmpeacemonitor Mapping: http://www.myhistro.com/stories/info.mmpeacemonitor Contents Notes to the reader: . v Executive Summary . vi Acronyms . vii Grand Map of the Peace Process: Introduction . 1 Tracking peace and conlict: An overview . 2 I. Conlict Analysis 2015-2016 . 4 Number of conlicts per EAG 2015 and 2016 . 4 EAO expansions between 2011 - 2016 . 5 The Northern Alliance and continuing armed struggle . 6 Major military incidents per group . 8 Minor Tensions: . 9 Inter-EAG conlicts . 10 Number of clashes or tensions investigated or resolved diplomatically . 10 Armed Groups outside the Peace Process . 12 New Myanmar Army crackdown in Rakhine state . 13 Roots of Rakhine-Rohingya conlict . 15 Spillover of crisis . 16 Repercussions of war . 18 IDPs . 18 Drug production . 20 Communal Conlict . 23 II. The Peace Process Roadmap . 25 Current roadmap . 25 Nationwide Ceaseire Agreement . 29 Step 1: NCA signing . 31 New structure and mechanisms of the NCA peace process . 34 JICM - Nationwide Ceaseire Agreement Joint Implementation Coordination Meeting . -

Myanmar's Evolving Relations

Myanmar’s Evolving Relations: The NLD in Government Kyaw Sein and Nicholas Farrelly ASIA PAPER October 2016 Myanmar’s Evolving Relations: The NLD in Government Kyaw Sein Nicholas Farrelly Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu Evolving Relations in Myanmar: The NLD in Government is an Asia Paper published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. Through its Silk Road Studies Program, the Institute runs a joint Transatlantic Research and Policy Center with the Central Asia-Caucasus Institute of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it func- tions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibil- ity for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copy- right holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. -

News Bulletin Issue (19) Thursday, 24Th November 2016

State and Region Parliaments News Bulletin Issue (19) _ Thursday, 24th November 2016 Photo News Ethnic Affairs Ministers Attended the Workshop on Federalism 17th November 2016 A workshop on federalism was held President Hotel, Naypyidaw. U Naing Thetby Euro-Burma Lwin, the Union Office Minister (EBO) ofat EthnicRoyal Affairs and, the state and region ethnic affairs ministers attended the workshop. U Naing Thet Lwin urged participants to discuss openly on power sharing and needs if federalism shall be put into practice. During the two-day workshop, the participants claimed that historical “Red Cross Knowledge Sharing Workshop” being held at Kachin State Hluttaw on and fundamental factors have to be tak- 17th and 18th November. en into account so that compatible feder- (Ref: Kachin State Hluttaw Facebook Page) alism can be established. (Ref: Extracted from www.7daydaily.com) Concerns over Metal Panels Around the North of Pine Forest to Build Shan State New Parliament Building st 21 November 2016 built in a site which does not require any The Shan State Cabinet would not trees to be cut down. We are worried be- allow to build the new parliament in Taunggyi-based environmental cause the company has set up metal pan- the pine forest which the locals have groups are concerned over the metal els. We will oppose if they plan to cut been opposing, but in the site which panels being set up around the north of down any trees,” said Ko Thet Paing Soe does not require any cutting down of pine forest, in Eaintawyar Street, Taung- who is involved in enviroment protec- tress, mentioned Dr.