Black Rhythm, White Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: the 1970S: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Student Study Outline

Starr-Waterman American Popular Music Chapter 11: The 1970s: Rock Music, Disco, and the Popular Mainstream Student Study Outline I. The “Me” Decade a. Tom Wolfe’s label b. Music industry reached new heights of consolidation II. Singer-Songwriters: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor a. Carole King (b. 1942): career illustrates the central prominence of singer- songwriters in this period i. Tapestry (1971): album whose success made King a major recording star b. Joni Mitchell (b. 1943): began career as songwriter, started recording on her own in 1968 i. Blue (1971): best-known album; cycle of songs about complexity of love c. James Taylor (b. 1948): perhaps the most successful long-running career of the 1970s era singer-songwriters i. Sweet Baby James (1970): hugely successful album with many hit singles, including number three hit “Fire and Rain.” III. Country Music and the Pop Mainstream a. Country-pop crossover accomplished by a new generation of musicians: i. Glen Campbell (b. 1936) ii. Charlie Rich (b. 1932) iii. Olivia Newton-John (b. 1948) iv. Dolly Parton (b. 1946) v. John Denver (1943‒1997) IV. Box 11.1: Hardcore Country: Merle Haggard and the Bakersfield Sound a. Merle Haggard (b. 1937) V. Country Rock: The Eagles a. The Eagles: influential band who epitomized the culture of Southern California i. Ambitious saga “Hotel California” cashed in on this association VI. Rock Comes of Age a. Pop rock and soft rock i. Elton John (b.1947): continued trend of long-running “British occupation” of the American pop charts 1. “Crocodile Rock” and nostalgia b. -

Funk Is Its Own Reward": an Analysis of Selected Lyrics In

ABSTRACT AFRICAN-AMERICAN STUDIES LACY, TRAVIS K. B.A. CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY DOMINGUEZ HILLS, 2000 "FUNK IS ITS OWN REWARD": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED LYRICS IN POPULAR FUNK MUSIC OF THE 1970s Advisor: Professor Daniel 0. Black Thesis dated July 2008 This research examined popular funk music as the social and political voice of African Americans during the era of the seventies. The objective of this research was to reveal the messages found in the lyrics as they commented on the climate of the times for African Americans of that era. A content analysis method was used to study the lyrics of popular funk music. This method allowed the researcher to scrutinize the lyrics in the context of their creation. When theories on the black vernacular and its historical roles found in African-American literature and music respectively were used in tandem with content analysis, it brought to light the voice of popular funk music of the seventies. This research will be useful in terms of using popular funk music as a tool to research the history of African Americans from the seventies to the present. The research herein concludes that popular funk music lyrics espoused the sentiments of the African-American community as it utilized a culturally familiar vernacular and prose to express the evolving sociopolitical themes amid the changing conditions of the seventies era. "FUNK IS ITS OWN REWARD": AN ANALYSIS OF SELECTED LYRICS IN POPULAR FUNK MUSIC OF THE 1970s A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THEDEGREEOFMASTEROFARTS BY TRAVIS K. -

07-18905 Cover Creating Racism.Indd

INTRODUCTION The Creation of Racism n the United States, African-American and to receive electroshock treatment (over 400 volts Hispanic children in predominantly white of electricity sent searing through the brain to school districts are classified as “learning control or alter a person’s behavior) and to be disabled” more often than Whites. This subjected to physical and chemical restraints.3 leads to millions of minority children Around the world, racial minority groups beingI hooked onto prescribed mind-altering continue to come under assault. The effects are drugs — some more potent than cocaine — to obvious: poverty, broken families, ruined youth, “treat” this “mental disorder.” And yet, with and even genocide (deliberate destruction of a early reading instruction, the number of students race or culture). No matter how loud the plead- so classified could be reduced by up to 70%.1 ings or sincere the efforts of our religious lead- African-Americans and Hispanics are also ers, our politicians and our teachers, racism just significantly over-represented in U.S. prisons. seems to persist. In Britain, black men are 10 times more Yes, racism persists. But why? Rather than likely than white men to be diagnosed as “schizo- struggle unsuccessfully with the answer to this phrenic,” and more likely to be prescribed and question, there is a better question to ask. Who? given higher doses of powerful psychotropic The truth is we will not fully understand (mind-altering) drugs.2 They are also more likely racism until we recognize that two largely A Message from Isaac Hayes “Psychiatric programs and drugs have ravaged our inner cities, helping to create criminals of our young people, and all because psychiatrists and psychologists were allowed to practice racist behavioral control and experimentation in our schools, instead of leaving teachers just to teach. -

Barry White Let the Music Play Mp3, Flac, Wma

Barry White Let The Music Play mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Funk / Soul Album: Let The Music Play Country: Italy Released: 1976 Style: Soul, Disco MP3 version RAR size: 1793 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1960 mb WMA version RAR size: 1449 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 151 Other Formats: AU MPC AUD WAV ASF AHX XM Tracklist Hide Credits A1 I Don't Know Where Love Has Gone 4:57 A2 If You Know, Won't You Tell Me 5:04 A3 I'm So Blue And You Are Too 7:04 B1 Baby, We Better Try To Get It Together 4:25 You See The Trouble With Me B2 3:29 Written-By – Ray Parker* B3 Let The Music Play 6:15 Credits Arranged By, Artwork [Concept], Conductor, Mixed By, Producer, Written-By – Barry White Engineer – Barney Perkins Engineer, Mixed By – Frank Kejmar Notes A Soul Unlimited Inc. Production Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Barry Let The Music Play (LP, 20th Century T-502 T-502 US 1976 White Album) Records Barry Let The Music Play (LP, 6370241 Philips 6370241 Colombia 1976 White Album) Barry Let The Music Play (LP, 20th Century 6370 241 6370 241 Germany 1976 White Album, Promo) Records Barry Let The Music Play (CD, 314 532 167-2 Mercury 314 532 167-2 US 1996 White Album, RE, RM) Barry Let The Music Play (LP, 20th Century STEC 208 STEC 208 France 1976 White Album) Records Related Music albums to Let The Music Play by Barry White Barry White - You See The Trouble With Me / I'm So Blue And You Are Too Barry White, Love Unlimited & Love Unlimited Orchestra - Best Of Barry White, Love Unlimited / Love Unlimited Orchestra Barry White - Baby, We Better Try To Get It Together Love Unlimited - In Heat Barry White - Barry White Sings For Someone You Love Barry White - Is This Whatcha Wont? Barry White - Barry White The Man Barry White - The Barry White Story, Let The Musi Play Barry White - Stone Gon' Barry White - Just Another Way To Say I Love You / Otra Forma De Decir "Te Quiero". -

WDAM Radio's History of Dionne Warwick

WDAM Radio's Hit Singles History Of Dionne Warwick # Artist Title Chart Position/Year Label Comments 001 Drifters “Mexican Divorce” –/1962 Atlantic Dionne Warwick’s back-up vocals on this recording are what caught the attention of Hal David & Burt Bacharach, who signed her to their production company. Recorded in 1961, but released as the B-side of When My Little Girl Is Smiling (#28-Rock-U.S. + #31- U.K./1962). Composers – Burt Bacharach & Bob Hilliard. 002 Burt & The Backbeats “Move It On The Backbeat” –/1961 Big Top Burt Bacharach, Dionne Warwick & Dee Dee Warwick. Composers – Hal David & Burt Bacharach. 003 Dionne Warwick “It’s Love That Really Counts” –/1962 Scepter Demo for song that was presented to the Shirelles. It also was a cut on Dionne’s debut LP – Presenting Dionne Warwick – released in 1963. Composers – Hal David & Burt Bacharach. 003A Shirelles “It’s Love That Really Counts” #102/1962 Scepter 004 Dionne Warwick “I Smiled Yesterday” –/1962 Scepter A-Side. Composers – Hal David & Burt Bacharach. 005 Dionne Warwick “Don’t Make Me Over” #21-Rock & #5-R&B- Scepter B-side. Song title inspired by Dionne’s angry U.S. + #38-Rock- statement to Hal David & Burt Bacharach Canada/1962 gave Make It Easy On Yourself to Jerry Butler first instead of her. Composers – Hal David & Burt Bacharach. 005A Swinging Blue Jeans “Don’t Make Me Over” #116-Rock-U.S. + #31- Imperial U.K./1966 005B Brenda & The “Don’t Make Me Over” #77-Rock & #15-R&B- Top And Bottom Co-producer – Van McCoy. Tabulations U.S./1970 005C Jennifer Warnes “Don’t Make Me Over” #67-Rock, #14-AC & Arista #84-C&W-U.S./1980 005D Sybil “Don’t Make Me Over” #20-Rock, #2-R&B & Next Plateau #4-Dance-U.S. -

Troubled Ethnicities in American Popular Music from Elvis Presley to Eminem

TROUBLED ETHNICITIES IN AMERICAN POPULAR MUSIC FROM ELVIS PRESLEY TO EMINEM Stefan L. Brandt (University of Siegen, Germany / Harvard University) With the commodification of African American culture, Blackness has become an accessory that can be put on like burnt cork and hog fat: baggy pants, overpriced athletic shoes, corn rows or dread locks, gaudy jewelry, swiveling necks, snapping fingers, absent consonants.1 Introduction: Blackface, White Negritude, and Ethnic Identity On July 18, 1953, an 18-year old trucker named Elvis Presley decided to go to the Sun Record Company in Memphis and paid $3.98 to record a demo – a procedure that he repeated in January of 1954. It took another four months until Sun Records founder Sam Phillips, eager to capitalize upon the popularity of African American songs, accidentally discovered one of the tapes and took Presley under contract. Presley’s music, a combination of Rhythm & Blues, hillbilly, gospel, and boogie-woogie, dominated by an uptempo, backbeat-driven rhythm, was an instant success. Some forty years later, American popular music saw another successful ‘hybrid’ artist in the shape of Missouri-born white rapper Marshall Bruce Mathers III, better known as “Eminem” or “Slim Shady.” Like Elvis before him, Eminem cleverly took advantage of the appeal of a ‘black’ music style, in his case HipHop, integrating it into a mass-compatible crossover product. Eminem’s video clips are masterstrokes of ethnic marketing, deploying elements of ‘white trash’ imagery as well as of ‘black’ language and art. My essay is interested in those strategies of representation within American popular music that are designed to market what Harry J. -

Vinyls-Collection.Com Page 1/64 - Total : 2469 Vinyls Au 23/09/2021 Collection "Pop/Rock International" De Lolivejazz

Collection "Pop/Rock international" de lolivejazz Artiste Titre Format Ref Pays de pressage 220 Volt Mind Over Muscle LP 26254 Pays-Bas 50 Cent Power Of The Dollar Maxi 33T 44 79479 Etats Unis Amerique A-ha The Singles 1984-2004 LP Inconnu Aardvark Aardvark LP SDN 17 Royaume-Uni Ac/dc T.n.t. LP APLPA. 016 Australie Ac/dc Rock Or Bust LP 88875 03484 1 EU Ac/dc Let There Be Rock LP ALT 50366 Allemagne Ac/dc If You Want Blood You've Got I...LP ATL 50532 Allemagne Ac/dc Highway To Hell LP ATL 50628 Allemagne Ac/dc High Voltage LP ATL 50257 Allemagne Ac/dc High Voltage LP 50257 France Ac/dc For Those About To Rock We Sal...LP ATL 50851 Allemagne Ac/dc Fly On The Wall LP 781 263-1 Allemagne Ac/dc Flick Of The Switch LP 78-0100-1 Allemagne Ac/dc Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap LP ATL 50 323 Allemagne Ac/dc Blow Up Your Video LP Inconnu Ac/dc Back In Black LP ALT 50735 Allemagne Accept Restless & Wild LP 810987-1 France Accept Metal Heart LP 825 393-1 France Accept Balls To The Walls LP 815 731-1 France Adam And The Ants Kings Of The Wild Frontier LP 84549 Pays-Bas Adam Ant Friend Or Foe LP 25040 Pays-Bas Adams Bryan Into The Fire LP 393907-1 Inconnu Adams Bryan Cuts Like A Knife LP 394 919-1 Allemagne Aerosmith Rocks LP 81379 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Live ! Bootleg 2LP 88325 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Get Your Wings LP S 80015 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Classics Live! LP 26901 Pays-Bas Aerosmith Aerosmith's Greatest Hits LP 84704 Pays-Bas Afrika Bambaataa & Soulsonic F.. -

WEDDING RECEPTION RECOMMENDATION MUSIC BRIDAL PARTY INTRODUCTIONS You Shook Me All Night Long – AC/DC Space Age Love Song S

WEDDING RECEPTION RECOMMENDATION MUSIC BRIDAL PARTY INTRODUCTIONS You Shook Me All Night Long – AC/DC I’m A Believer – The Monkees Space Age Love Song – A Flock Of Seagulls L.O.V.E – Nat King Cole Sirius (Chicago Bulls Theme) – Alan Parsons The Godfather Theme -- Nougat Project No One (Instrumental) – Alicia Keys Across The Field – Ohio State University Bandstand Boogie – Barry Manilow Two Hearts – Phill Collins All You Need Is Love – The Beatles Get The Party Started – Pink Crazy In Love – Beyonce You’re My Best Friend – Queen I Gotta Feeling – Black Eyed Peas Another One Bites The Dust – Queen Let’s Get It Started – Black Eyed Peas Soul Bossa Nova (Austin Powers Theme) – Boom Boom Pow – Black Eyed Peas Quincy Jones Carmina Burana, It’s The End Of The World As We Know It (And O Fortuna – Boston Symphony Orchestra I Feel Fine) – R.E.M Get Ready To Bounce – Brooklyn Bounce The Cup Of Life – Ricky Martin Clocks – Coldplay Viva La Vida Living La Vida Loca (Instrumental) – Ricky (Instrumental) – Coldplay Martin One More Time – Daft Punk She Bangs – (Instrumental) – Ricky Martin Two Step – Dave Matthew Band Umbrella - Rihanna Groove Is In The Heart – Dee Lite Misirlou – Salsa Rosso (Pulp Fiction Chapel Of Love – Dixie Cups Boogie Soundtrack) Wonderland – Earth, Wind, & Fire From This Moment – Shania Twain Circle Of Life – Elton John Party Like A Rock Star (Clean) – Shop Boyz Unbelievable -- EMF We Are Family – Sister At Last – Etta James Sledge 2001: A Space Odyssey – Slovak The Final Countdown -- Europe Philharmonic Orchestra Welcome To The -

Roots and Branches Handout SESSIONS Revnov20

THE LIVING, BREATHING ART OF MUSIC HISTORY: THE ROOTS AND BRANCHES COURTESY OF WWW.THESESSIONS.ORG COUNTRY: THE ROOTS: The Carter Family/Roy Acuff/Kitty Wells/Hank Williams/Bob Wills & His Texas Playboys BRANCHES: Men: Johnny Cash/George Jones/Waylon Jennings/Conway Twitty/Charlie Pride/The Everly Brothers (see also Rock n’ Roll) WOMEN: Patsy Cline/Loretta Lynn/June Carter/Tammy Wynette/ Dolly Parton INFLUENCED: Jack White, Zac Brown TRIBUTARY: BLUEGRASS : Bill Monroe/Ralph & Carter Stanley/Ricky Scaggs/Allison Krauss TRIBUTARY: COUNTRY ROCK: The Byrds (“Sweetheart Of The Rodeo”)/Poco/early Eagles/Graham Parsons/Emmylou Harris THE BLUES: THE ROOTS (Men): (Delta) Robert Johnson /Son House /Charlie Patton/Mississippi John Hurt/WC Handy/Lonnie Johnson (Chicago) Muddy Waters/Howlin’ Wolf/Little Walter /Buddy Guy/Otis Rush/Elmore James/Jimmy Reed - (Detroit) John Lee Hooker - (Mississippi) BB King/Albert King - (Texas) Freddie King BRANCHES: Stevie Ray Vaughn/Jimi Hendrix/Led Zepplin/ The Fabulous Thunderbirds/Cream/Eric Clapton/early Fleetwood Mac/Allman Brothers/Santana/Paul Butterfield Blues Band MODERN: Robert Cray/Joe Bonamassa/ Warren Haynes/Keb Mo TRIBUTARY- TRANCE BLUES-Oxford MS -Black Possum Records—RL Burnside, Junior Kimbrough (The Black Keys are their disciples) THE BLUES: THE ROOTS (Women): Ma Rainey/Bessie Smith/Sister Rosetta Tharpe (see also “Rock and Roll”) Memphis Minnie (influenced Led Zepplin) BRANCHES (including Jazz) : Billie Holiday/ Dinah Washington/Peggy Lee/Lena Horne/Janis Joplin/Paul Butterfield Blues Band/Michael -

WDAM Radio's History of the Animals

Listener’s Guide To “WDAM Radio’s History Of James Bond” You have security clearance to enjoy “WDAM Radio’s History Of James Bond.” Classified – until now, this is the most comprehensive top secret dossier of ditties from James Bond television and film productions ever assembled. WDAM Radio’s undercover record researchers have uncovered all the opening title themes, as well as “secondary songs” and various end title themes worth having. Our secret musicology agents also have gathered intelligence on virtually every known and verifiable* song that was submitted to and rejected by the various James Bond movie producers as proposed theme music. All of us at the station hope you will enjoy this musical license to thrill.** Rock on. Radio Dave *There is a significant amount of dubious data on Wikipedia and YouTube with respect to songs that were proposed, but not accepted, for various James Bond films. Using proprietary alga rhythms (a/k/a Radio Dave’s memory and WDAM Radio’s Groove Yard archives), as well as identifying obvious inconsistencies on several postings purporting to present such claims, we have revoked the license of such songs to be included in this collection. (For instance, two sites claim Elvis Presley songs that were included in two of his movies were originally proposed to the James Bond producers – not true.) **Watch for updates to this dossier as future James Bond films are issued, as well as additional “rejected songs” to existing films are identified and obtained via our ongoing overt and covert musicology surveillance activities. WDAM Radio's History Of James Bond # Film/Title (+ Year) Artist & (Composer) James Bond Chart Comments Position/ Year* 01 Casino Royale (1954) Barry Nelson 1954 Episode of Climax! Mystery Theater broadcast live on 10/21/1954 starring Barry Nelson. -

Beantown Song List 2010

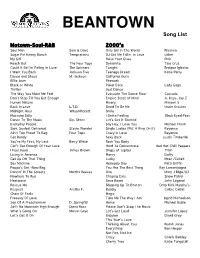

BEANTOWN Song List Motown-Soul-R&B 2000’s Soul Man Sam & Dave Only Girl In The World Rhianna Sugar Pie Honey Bunch Temptations DJ Got Me Fallin in Love Usher My Girl Raise Your Glass Pink Reach Out The Four Tops Dynamite Taio Cruz Could It Be I’m Falling In Love The Spinners Tonight Enrique Iglesias I Want You Back Jackson Five Teenage Dream Katie Perry Dance and Shout M. Jackson California Gurls Billie Jean FIrework Black or White Poker Face Lady Gaga Thriller Just Dance The Way You Make Me Feel Evacuate The Dance Floor Cascada Don’t Stop Till You Get Enough Empire State of Mind A. Keys, Jay Z Human Nature Misery Maroon 5 Back In Love L.T.D. Good To Be Me Uncle Kracker Midnight Hour WilsonPickett Smile Mustang Sally I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas Dance To The Music Sly. Stone Let’s Get It Started Everyday People Say Hey, I Love You Michael Franti Sign, Sealed, Delivered Stevie Wonder Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) Beyonce Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Four Tops Crazy In Love Beyonce Get Ready Sexy Back Justin Timberlak You’re My First, My Last Barry White Rock You Body Can’t Get Enough Of Your Love Hard To Concentrate Red Hot Chilli Peppers I Feel Good James Brown Drops of Jupiter Train Living In America Mercy Duffy Get Up Off That Thing Lucky Mraz /Collait Sex Machine Heavenly Day Patti Griffin Poppa’s Got -New Bag You Are The Best Thing Ray Lamontaigne Dancin’ In The Streets Martha Reeves One Mary J Blige/U2 Nowhere To Run Chasing Cars Snow Patrol Heatwave Save Room John Legend Rescue Me Shipping Up To Boston Drop Kick Murphy’s Respect Aretha F.