Nigeria Military Injustice Military Injustice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015)

Violent Conflict in Divided Societies The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015) Nigeria Conflict Security Analysis Network (NCSAN) World Watch Research November, 2015 [email protected] www.theanalytical.org 1 Violent Conflict in Divided Societies The Case Study of Violent Conflict in Taraba State (2013 - 2015) Taraba State, Nigeria. Source: NCSAN. The Deeper Reality of the Violent Conflict in Taraba State and the Plight of Christians Nigeria Conflict and Security Analysis Network (NCSAN) Working Paper No. 2, Abuja, Nigeria November, 2015 Authors: Abdulbarkindo Adamu and Alupse Ben Commissioned by World Watch Research, Open Doors International, Netherlands No copyright - This work is the property of World Watch Research (WWR), the research department of Open Doors International. This work may be freely used, and spread, but with acknowledgement of WWR. 2 Acknowledgements The authors acknowledge with gratitude all that granted NCSAN interviews or presented documented evidence on the ongoing killing of Christians in Taraba State. We thank the Catholic Secretariat, Catholic Diocese of Jalingo for their assistance in many respects. We also thank the Chairman of the Muslim Council, Taraba State, for accepting to be interviewed during the process of data collection for this project. We also extend thanks to NKST pastors as well as to pastors of CRCN in Wukari and Ibi axis of Taraba State. Disclaimers Hausa-Fulani Muslim herdsmen: Throughout this paper, the phrase Hausa-Fulani Muslim herdsmen is used to designate those responsible for the attacks against indigenous Christian communities in Taraba State. However, the study is fully aware that in most reports across northern Nigeria, the term Fulani herdsmen is also in use. -

(But Limited) Impact of Human Rights Ngos on Legislative and Executive Behaviour in Nigeria

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Articles & Book Chapters Faculty Scholarship 2004 Modest Harvests: On the Significant (But Limited) Impact of Human Rights NGOs on Legislative and Executive Behaviour in Nigeria Obiora Chinedu Okafor Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Source Publication: Journal of African Law. Volume 48, Number 1 (2004), p. 23-49. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Okafor, Obiora Chinedu. "Modest Harvests: On the Significant (But Limited) Impact of Human Rights NGOs on Legislative and Executive Behaviour in Nigeria." Journal of African Law 48.1 (2004): 23-49. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Journalof African Law, 48, 1 (2004), 23-49 © School of Oriental and African Studies. DOI: 10.1017/S0021855304481029 Printed in the United Kingdom. MODEST HARVESTS: ON THE SIGNIFICANT (BUT LIMITED) IMPACT OF HUMAN RIGHTS NGOS ON LEGISLATIVE AND EXECUTIVE BEHAVIOUR IN NIGERIA OBIORA CHINEDU OKAFOR* INTRODUCTION This article is devoted to the highly important task of mapping, contextualizing and highlighting the significance of some of the modest achieve- ments that have been made by domestic human rights NGOs in Nigeria. 1 As limited as the development of these NGOs into much more popular (and therefore more influential) movements has tended to be, they have none- 2 theless been able to exert significant, albeit modest, influence within Nigeria. -

EXTERNAL (For General Distribution) AI Index: AFR 44/01/93 Distr: UA/SC

EXTERNAL (for general distribution) AI Index: AFR 44/01/93 Distr: UA/SC UA 27/93 Death Penalty 4 February 1993 NIGERIA: Major-General Zamani LEKWOT and six others Seven members of the Kataf ethnic group have been sentenced to death for murder in connection with religious riots in northern Nigeria in May 1992. Amnesty International is concerned that they have no right of appeal against conviction and sentence, and that they could therefore be executed imminently. The organization calls urgently for the commutation of the sentences. On 2 February 1993 the Civil Disturbances Special Tribunal in Kaduna convicted Major-General Zamani Lekwot, a retired army officer, and six others of "culpable homicide punishable by death". The defendants were sentenced to death by hanging. Their convictions were in connection with riots in Kaduna State in May 1992 in which over 100 people were killed in violent clashes between Christians belonging to the Kataf ethnic group and Muslims belonging to the Hausa community. According to some press reports, as many as 3,000 may have been killed. Major-General Lekwot and other Kataf leaders were detained without charge until 29 July 1992 when six of them were charged with unlawful assembly. The Civil Disturbances Special Tribunal acquitted the six on 18 August 1992, but they were immediately rearrested. Zamani Lekwot and six others were charged on 4 September 1992 with culpable homicide, a charge which carries a possible death sentence, and other offences. Twenty others were also tried in connection with the riots, but were acquitted. The Civil Disturbances (Special Tribunal) Decree, No. -

Nigeria's Great Speeches in History

Nigeria’s Great Speeches in History The Speech Declaring Nigeria’s Independence by Nigeria’s First Prime Minister Alhaji Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa – October 1, 1960 Today is Independence Day. The first of October 1960 is a date to which for two years, Nigeria has been eagerly looking forward. At last, our great day has arrived, and Nigeria is now indeed an independent Sovereign nation. Words cannot adequately express my joy and pride at being the Nigerian citizen privileged to accept from Her Royal Highness these Constitutional Instruments which are the symbols of Nigeria’s Independence. It is a unique privilege which I shall remember forever, and it gives me strength and courage as I dedicate my life to the service of our country. This is a wonderful day, and it is all the more wonderful because we have awaited it with increasing impatience, compelled to watch one country after another overtaking us on the road when we had so nearly reached our goal. But now, we have acquired our rightful status, and I feel sure that history will show that the building of our nation proceeded at the wisest pace: it has been thorough, and Nigeria now stands well-built upon firm foundations. Today’s ceremony marks the culmination of a process which began fifteen years ago and has now reached a happy and successful conclusion. It is with justifiable pride that we claim the achievement of our Independence to be unparalleled in the annals of history. Each step of our constitutional advance has been purposefully and peacefully planned with full and open consultation, not only between representatives of all the various interests in Nigeria but in harmonious cooperation with the administering power which has today relinquished its authority. -

An Assessment of Civil Military Relations in Nigeria As an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007

AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 BY MOHAMMED LAWAL TAFIDA DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA NIGERIA JUNE 2015 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis entitled An Assessment of Civil-Military Relations in Nigeria as an Emerging Democracy, 1999-2007 has been carried out and written by me under the supervision of Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi, Dr. Mohamed Faal and Professor Paul Pindar Izah in the Department of Political Science and International Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria. The information derived from the literature has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided in the work. No part of this dissertation has been previously presented for another degree programme in any university. Mohammed Lawal TAFIDA ____________________ _____________________ Signature Date CERTIFICATION PAGE This thesis entitled: AN ASSESSMENT OF CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN NIGERIA AS AN EMERGING DEMOCRACY, 1999-2007 meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science of the Ahmadu Bello University Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. Dr. Hudu Ayuba Abdullahi ___________________ ________________ Chairman, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Dr. Mohamed Faal________ ___________________ _______________ Member, Supervisory Committee Signature Date Professor Paul Pindar Izah ___________________ -

In Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria

HUMAN “Leave Everything to God” RIGHTS Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence WATCH in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria “Leave Everything to God” Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0855 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org DECEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0855 “Leave Everything to God” Accountability for Inter-Communal Violence in Plateau and Kaduna States, Nigeria Summary and Recommendations .................................................................................................... -

Bayero University Kano (BUK)

BAYERO UNIVERSITY, KANO SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES FIRSFIRSTT BATCH ADMISSIONS OF 2019/2020 SESSION Faculty of Agriculture Department: Agricultural Economics and Extension Ph.D Agricultural Economics (Livelihood and Natural Resources Economics) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 DGBH 776 Ashafa Salisu SAMBO 2 TQJX 4560 Sesugh UKER 3 KQBL 8701 Nasiru Bako SANI Ph.D Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1006) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 FRDZ 3835 Umar Karaye IBRAHIM 2 GTDJ 2099 Salmanu Safiyanu ABDULSALAM M.Sc Agricultural Economics (Livelihood and Natural Resources Economics) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 HDYQ 1451 Simon Okechukwu AGBO 2 QKGW 1814 Linda Imuetiyan IRENE 3 NVPD 2548 Mary Adebukola ALAMU 4 WBKX 3667 Muhammad Baba FUGU 5 ZXCL 4612 Mojisola Feyisikemi OLUFEMI 6 LNQT 4158 Hafsat Murtala SALIM 7 LRMT 6006 Usman Abdullahi IDRIS 8 RWMF 5114 Abdullahi Ibrahim DUMBULUN 9 DCVZ 8142 Yusuf MIKO GUMEL M.Sc Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1002) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 KMLH 1927 Samir Hussaini USMAN 2 QZDY 1730 Mercy Oluwafunmike OLANIYI 3 WTGC 3166 Muhammad Imam IBRAHIM 4 DCQV 3116 Patrick Ojiya ADOLE 5 VPHQ 3788 Rukayya Rabiu YUSUF 6 RQXM 5855 Kassim Shuaib AUDU 7 TQMN 6574 Najiba Musa MUMAMMAD 8 ZLPT 7218 Daniel Jarafu MAMZA First Batch of 2019/2020 PG Admission List Page 1 of 168 M.Sc Agricultural Extension(Programme ID:1003) Application S/N Invoice No. Full Name No. 1 TKCX 6389 Asogah Solomon EDOH 2 MQPD 4837 Murtala SULE 3 HWZP 6307 Aminu Rdoruwa IBRAHIM 4 MRGT 6681 Ruth Nwang JONATHAN Department: Agronomy Ph.D Agronomy(Programme ID:1108) Application S/N Invoice No. -

Page 1 of 27 Nigeria and the Politics of Unreason 7/21/2008

Nigeria and the Politics of Unreason Page 1 of 27 Nigeria and the Politics of Unreason: Political Assassinations, Decampments, Moneybags, and Public Protests By Victor E. Dike Introduction The problems facing Nigeria emanate from many fronts, which include irrational behavior (actions) of the political elite, politics of division, and politics devoid of political ideology. Others factors are corruption and poverty, lack of distributive justice, regional, and religious cleavages. All these combine to create crises (riots and conflicts) in the polity, culminating in public desperation and insecurity, politics of assassinations, decampments (carpet crossing), moneybags, and public protests. All this reached its climax during the 2003 elections. When the nation thinks it is shifting away from these forces, they would somersault and clash again creating another political thunderstorm. It looks that the society would hardly outgrow ‘the politics of unreason’ (Lipset and Raab, 1970), which is often politics of extremism, because the political class is always going beyond the limits of what are reasonable to secure or retain political power. During the 2003 elections moneybags (instead of political ideology) directed political actions in political parties; and it also influenced the activities of many politicians. As a result, the presidential candidates of the two major political parties (PDP and ANPP) cliched their party tickets by stuffing the car boots, so to say, of their party delegates with Ghana-Must- Go bags. This frustrated and intimidated their political opponents within (and those in the other minor political parties). Since after his defeat by Chief Olusegun Obasanjo in the 2003 PDP primary in Abuja, Dr. -

The Making of Sani Abacha There

To the memory of Bashorun M.K.O Abiola (August 24, 1937 to July 7, 1998); and the numerous other Nigerians who died in the hands of the military authorities during the struggle to enthrone democracy in Nigeria. ‘The cause endures, the HOPE still lives, the dream shall never die…’ onderful: It is amazing how Nigerians hardly learn frWom history, how the history of our politics is that of oppor - tunism, and violations of the people’s sovereignty. After the exit of British colonialism, a new set of local imperi - alists in military uniform and civilian garb assumed power and have consistently proven to be worse than those they suc - ceeded. These new vetoists are not driven by any love of coun - try, but rather by the love of self, and the preservation of the narrow interests of the power-class that they represent. They do not see leadership as an opportunity to serve, but as an av - enue to loot the public treasury; they do not see politics as a platform for development, but as something to be captured by any means possible. One after the other, these hunters of fortune in public life have ended up as victims of their own ambitions; they are either eliminated by other forces also seeking power, or they run into a dead-end. In the face of this leadership deficit, it is the people of Nigeria that have suffered; it is society itself that pays the price for the imposition of deranged values on the public space; much ten - sion is created, the country is polarized, growth is truncated. -

Objectives of the Conference Included

ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ANUCHA, DOMINIC U M.A. FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON UNIVERSITY, 1972 LL.B. LONDON UNIVERSITY, 1966 THE IMPACT OF CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLIES (1978-1995) ON NIGERIAN CONSTITUTIONS AND POLITICAL EVOLUTION Advisor: Dr. Hashim Gibrill Dissertation dated July 2010 This dissertation addresses the issues of crafting a constitution for Nigeria that would meet the criteria of being visible, sustainable, and durable for national political unity, social and economic development. Specifically, it focuses on the years 1978 — 1995 during which several high profile systematic, constitution crafting exercises were undertaken. These included the establishment of a Constitution Drafting Committee to craft a constitution, and a Constituent Assembly. Ultimately, these exercises have proven to be only partially successful. The goal of producing an endurable constitutional framework for Nigerian politics remains elusive. The two core questions pursued in this dissertation focus on: Why did the military pursue these constitution crafting activities? What are the pressing political issues that the constitutional framework will have to manage? The dissertation pursued these issues through surveys, interviews, a review of government documents and reports, participant observation, and a review of existing literature regarding constitution development, federalism and Nigerian history and politics. Key research findings uncovered pressing political concerns ranging across ethnic fears, gender and youth concern, institutional restructuring and economic subordination. Our findings also related to the elite background of participants in these constitutional exercises, and the intrusion of religion, class, and geographical interests into the deliberations of the assemblies. The continued violation of constitutional provisions by the military was highlighted. The widespread call for a Sovereign National Constitutional Conference to shape a new popular constitution for the country was also a prominent concern. -

Nigeria: Threats to a New Democracy

June 1993 Vol. 5, No. 9 NIGERIA THREATS TO A NEW DEMOCRACY Human Rights Concerns at Election Time Table of Contents Introduction.............................................................................................1 Background ............................................................................................2 Transition Maneuvers........................................................................3 Attacks on Civil Society.....................................................................5 Rising Ethnic/Religious Conflict................................................10 The Treasonable Offenses Decree............................................21 Conclusion............................................................................................22 Recommendations........................................................................... 22 INTRODUCTION In the countdown to the June 12 presidential elections, the Nigerian military government has stepped up attacks on civil institutions, raising fears about its intentions to leave office as promised and, if it does leave, about the future stability of the country. The government's actions have included arresting and threatening human rights activists, closing two publications, arresting and detaining journalists, taking over the national bar association and threatening striking academics. Adding to fears has been the government's mishandling of ethnic and religious conflicts that have the potential to tear the country apart. In an investigation of violence between -

State Pensioners Verification Schedule 2021-Names

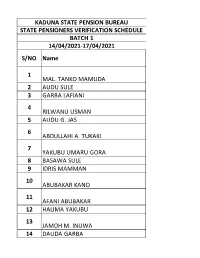

KADUNA STATE PENSION BUREAU STATE PENSIONERS VERIFICATION SCHEDULE BATCH 1 14/04/2021-17/04/2021 S/NO Name 1 MAL. TANKO MAMUDA 2 AUDU SULE 3 GARBA LAFIANI 4 RILWANU USMAN 5 AUDU G. JAS 6 ABDULLAHI A. TUKAKI 7 YAKUBU UMARU GORA 8 BASAWA SULE 9 IDRIS MAMMAN 10 ABUBAKAR KANO 11 AFANI ABUBAKAR 12 HALIMA YAKUBU 13 JAMOH M. INUWA 14 DAUDA GARBA 15 DAUDA M. UDAWA 16 TANKO MUSA 17 ABBAS USMAN 18 ADAMU CHORI 19 ADO SANI 20 BARAU ABUBAKAR JAFARU 21 BAWA A. TIKKU 22 BOBAI SHEMANG 23 DANAZUMI ABDU 24 DANJUMA A. MUSA 25 DANLADI ALI 26 DANZARIA LEMU 27 FATIMA YAKUBU 28 GANIYU A. ABDULRAHAMAN 29 GARBA ABBULLAHI 30 GARBA MAGAJI 31 GWAMMA TANKO 32 HAJARA BULUS 33 ISHAKU BORO 34 ISHAKU JOHN YOHANNA 35 LARABA IBRAHIM 36 MAL. USMAN ISHAKU 37 MARGRET MAMMAN 38 MOHAMMED ZUBAIRU 39 MUSA UMARU 40 RABO JAGABA 41 RABO TUKUR 42 SALE GOMA 43 SALISU DANLADI 44 SAMAILA MAIGARI 45 SILAS M. ISHAYA 46 SULE MUSA ZARIA 47 UTUNG BOBAI 48 YAHAYA AJAMU 49 YAKUBU S. RABIU 50 BAKO AUDU 51 SAMAILA MUSA 52 ISA IBRAHIM 53 ECCOS A. MBERE 54 PETER DOGO KAFARMA 55 ABDU YAKUBU 56 AKUT MAMMAN 57 GARBA MUSA 58 UMARU DANGARBA 59 EMMANUEL A. KANWAI 60 MARYAM MADAU 61 MUHAMMAD UMARU 62 MAL. ALIYU IBRAHIM 63 YANGA DANBAKI 64 MALAMA HAUWA IBRAHIM 65 DOGARA DOGO 66 GAIYA GIMBA 67 ABDU A. LAMBA 68 ZAKARI USMAN 69 MATHEW L MALLAM 70 HASSAN MAGAJI 71 DAUDA AUTA 72 YUSUF USMAN 73 EMMANUEL JAMES 74 MUSA MUHAMMAD 75 IBRAHIM ABUBAKAR BANKI 76 ABDULLAHI SHEHU 77 ALIYU WAKILI 78 DANLADI MUHAMMAD TOHU 79 MARCUS DANJUMA 80 LUKA ZONKWA 81 BADARAWA ADAMU 82 DANJUMA ISAH 83 LAWAL DOGO 84 GRACE THOT 85 LADI HAMZA 86 YAHAYA GARBA AHMADU 87 BABA A.