WRAP THESIS Roberts 2013.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5354/list-3-2016-accademia-della-crusca-aldine-device-1-bardi-giovanni-1534-1612-465354.webp)

List 3-2016 Accademia Della Crusca – Aldine Device 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]

LIST 3-2016 ACCADEMIA DELLA CRUSCA – ALDINE DEVICE 1) [BARDI, Giovanni (1534-1612)]. Ristretto delle grandeze di Roma al tempo della Repub. e de gl’Imperadori. Tratto con breve e distinto modo dal Lipsio e altri autori antichi. Dell’Incruscato Academico della Crusca. Trattato utile e dilettevole a tutti li studiosi delle cose antiche de’ Romani. Posto in luce per Gio. Agnolo Ruffinelli. Roma, Bartolomeo Bonfadino [for Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli], 1600. 8vo (155x98 mm); later cardboards; (16), 124, (2) pp. Lacking the last blank leaf. On the front pastedown and flyleaf engraved bookplates of Francesco Ricciardi de Vernaccia, Baron Landau, and G. Lizzani. On the title-page stamp of the Galletti Library, manuscript ownership’s in- scription (“Fran.co Casti”) at the bottom and manuscript initials “CR” on top. Ruffinelli’s device on the title-page. Some foxing and browning, but a good copy. FIRST AND ONLY EDITION of this guide of ancient Rome, mainly based on Iustus Lispius. The book was edited by Giovanni Angelo Ruffinelli and by him dedicated to Agostino Pallavicino. Ruff- inelli, who commissioned his editions to the main Roman typographers of the time, used as device the Aldine anchor and dolphin without the motto (cf. Il libro italiano del Cinquec- ento: produzione e commercio. Catalogo della mostra Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Roma 20 ottobre - 16 dicembre 1989, Rome, 1989, p. 119). Giovanni Maria Bardi, Count of Vernio, here dis- guised under the name of ‘Incruscato’, as he was called in the Accademia della Crusca, was born into a noble and rich family. He undertook the military career, participating to the war of Siena (1553-54), the defense of Malta against the Turks (1565) and the expedition against the Turks in Hun- gary (1594). -

Quaritch 2021

the Classical Tradition Quaritch 2021 B. Scalvini inv. A. Pasternack inc. ‘To read the Greek and Latin authors in their original is a sublime luxury... I thank on my knees, Him who directed my early education, for having put into my possession this rich source of delight; and I would not exchange it for anything which I could then have acquired’. Thus wrote Thomas Jefferson to Joseph Priestley. It was one of many manifest testimonials which, together with countless implicit quotations or references, a Founding Father owner of an exceptionally impressive library gave in celebration of his and his people’s Classical heritage. ‘The classical tradition is both so integrally and diffusely relevant to Western culture that much cultural development that seems unrelated to it is either implicated in it, even if (like Christianity) ultimately independent of it, or else arises, in significant part, out of it, even in reaction to it’ (The Classical Tradition: Art, Literature, Thought (2014), p. 248). Reflex, use, reconstitution, or response – the dialogue between modernity and the classical world, which began in the Renaissance, flourished in the early-modern era, and shaped the forming of America and modern Western societies, continues to enable our understanding of past and present. This short list is an eclectic gathering of books which represent moments in this rich tradition. N��-P�������� M��������: ��� ‘B����� �� T�� T�����’ �� W������ P��������� ������ 1. [ARISTOTLE and PLATO]. PSEUDO- ARISTOTLE. Oeconomica, seu de re familiari libri duo. Venice, Girolamo Scoto, 1540. [bound with:] [PLETHON, Georgios Gemistos]. DONATO, Bernardino. De Platonicae atque Aristotelicae philosophiae differentia. [With Plethon’s Peri hon Aristoteles pros Platona diapheretai, in Greek]. -

Introduction: the Translations of Renaissance Latin* Andrew Taylor Churchill College, Cambridge

Introduction: The Translations of Renaissance Latin* Andrew Taylor Churchill College, Cambridge Neo-Latin was the lingua franca of the cosmopolitan intellectual and literary culture 329 of Renaissance Europe, and was the language in which ideas and texts circulated among the Latinate elite. The names given to the profound, interrelated, but some- times dissonant cultural movements of the early modern period—‘Renaissance’, ‘Reformation’, ‘Scientific Revolution’—signal the critical turning away from inherited habits of thinking about humankind and its relationship to nature and supernature. Neo-Latin was the language in which newly recovered or discovered ideas tended to contest established and often deeply entrenched and institutionalised modes of inter- pretation and their linguistic forms. Humanists from the age of Petrarch onwards sought to reform Latin along the lines of the best classical models, with pedagogy, after a far briefer formal introduc- tion to grammar, focusing on the reading and imitation of these in the pursuit of pure classical usage (see Jensen). Once the teaching of Greek began to establish itself in Italy in the early fifteenth century (see Botley,Learning Greek), the practice of imita- tion and its related exercise in paraphrase from Latin into Latin expanded to include interlingual Greek-Latin transactions. The discussion of these rhetorical exercises for the orator in the treatises of Cicero and Quintilian deeply influenced ideas of human- ist translation as a display of eloquence (for example: Cicero’s De finibus 1.2.6 and 3.4.15; De oratore 1.3.155; the pseudo-Ciceronian De optimo genere oratorum 4.14; and Quintilian’s Institutio oratoria 10.5.9-25. -

WRAP THESIS Comiati 2015.Pdf

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/79572 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications HORACE IN THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE (1498-1600) BY GIACOMO COMIATI A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Studies University of Warwick, School of Modern Languages and Cultures, Italian Studies September 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments page 4 Abstract 5 List of Abbreviations 6 INTRODUCTION 8 1. RENAISSANCE BIOGRAPHERS OF HORACE 27 1.1 Fifteenth-Century Biographers 30 1.2 The First Printed Biographies 43 1.3 Biographies in the Sixteenth Century 53 Conclusion 66 2. RENAISSANCE COMMENTATORS OF HORACE 69 2.1 The Exegetical Fortune of Horace in the Late Quattrocento 71 2.2 Horatian Commentators: from Beroaldo the Elder to Girolamo Scoto 84 2.3 Horatian Exegesis 1550-1600 103 2.4 The Art of Poetry and its Exegesis 114 Conclusion 129 3. RENAISSANCE TRANSLATORS OF HORACE 133 3.1 Translating Horace’s Hexametrical Works 134 3.2 Translating Horace’s Lyrical Production 148 Conclusion 166 4. RENAISSANCE ITALIAN IMITATORS OF HORACE 169 4.1 The Satirical Genre 171 4.2 Vernacular Odes 188 4.3 The Founding Fathers of Petrarchism 210 2 4.4 Petrarchism After Bembo 220 4.4.1 Naples 220 4.4.2 Tuscany 230 4.4.3 Venetian Region 238 Conclusion 250 5. -

De Gulden Passer. Jaargang 47

De Gulden Passer. Jaargang 47 bron De Gulden Passer. Jaargang 47. De Nederlandsche Boekhandel, Antwerpen 1969 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_gul005196901_01/colofon.php © 2016 dbnl i.s.m. 1 [De Gulden Passer 1969] Allocution d'accueil Begroeting Par - door Aloïs Gerlo président du Comité Organisateur voorzitter van het Inrichtend Comitee L'année 1969 est l'année de la commémoration d'Érasme. Elle se trouve tout entière placée sous le signe du Prince de l'Humanisme, le plus grand auteur de la Renaissance, un des plus grands Européens par son esprit et à son époque probablement l'homme le plus célèbre du monde. La Belgique devait commémorer dignement le 500e anniversaire de la naissance d'Érasme, car l'humaniste de Rotterdam a vécu dans nos régions de 1502 à 1504 et de 1517 à 1521. Son influence sur la Cour, sur les milieux dirigeants et ceux des savants, y fut considérable. Érasme et Louvain, Érasme et Anvers, Bruges et Gand, Érasme et les imprimeurs des Pays-Bas Méridionaux, Érasme et Pierre Gillis, Érasme et Quentin Metsijs, Érasme et la Cour de Brabant, sont autant de chapitres importants de la biographie du grand humaniste. Le Centre interuniversitaire d'histoire de l'Humanisme n'a donc eu aucune peine à trouver un sujet approprié à la commémoration nationale d'Érasme dont il a pris l'initiative. Le thème ‘Érasme et la Belgique’ s'est imposé tout naturellement et pour notre colloque international et pour l'exposition organisée simultanément à la Bibliothèque Royale Albert Ier. Le rôle déterminant joué par Érasme dans la vie culturelle des Pays-Bas Méridionaux et sa De Gulden Passer. -

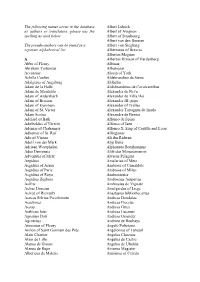

The Following Names Occur in the Database As Authors Or Translators

The following names occur in the database Albert Lübeck as authors or translators; please use the Albert of Avignon spelling as used below Albert of Strasbourg Albert van den Beesten The pseudo-authors can be found in a Albert von Siegburg separate alphabetical list Albertanus of Brescia Albertus Magnus A Albertus Rizaeus of Hardenberg Abbo of Fleury Albinus Abraham Tartuosus Albumasar Accursius Alcuin of York Achille Caulier Aldebrandino da Siena Adalgerus of Augsburg Aldhelm Adam de la Halle Aldobrandinus de Cavalcantibus Adam de Montaldo Alexander de Nevo Adam of Aldersbach Alexander de Villa Dei Adam of Bremen Alexander III, pope Adam of Eynsham Alexander of Tralles Adam of St. Victor Alexander Tartagnus de Imola Adam Scotus Alexandre de Bernai Adelard of Bath Alfonso de Spina Adelboldus of Utrecht Alfonso of Jaen Ademar of Chabannes Alfonso X, king of Castille and Leon Adhemar of St. Ruf Alfraganus Ado of Vienne Ali ibn Ridwan Adolf von der Mark Alijt Bake Adriaan Westphalen Alphonsus Bonihominis Adso Dervensis Altfridus Monasteriensis Adventius of Metz Alvarus Pelagius Aegidius Amalarius of Metz Aegidius of Assisi Ambrose of Camaldoli Aegidius of Paris Ambrose of Milan Aegidius of Roya Ambrosiaster Aegidius Zeghers Ambrosius Autpertus Aelfric Ambrosius de Vignate Aelius Donatus Amelgardus of Liege Aelred of Rievaulx Anastasius bibliothecarius Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini Andreas Dandulus Aeschines Andreas Floccus Aesop Andreas Gritti Aethicus Ister Andreas Lucanus Agostino Dati Andreas Osiander Agroecius Andrieu de Roubays Aimoinus