1 Children's Responses to Heroism in Roald Dahl's Matilda Abstract The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Review of Matilda Written by Roald Dahl Pronouncement

BOOK REVIEW OF MATILDA WRITTEN BY ROALD DAHL A FINAL PROJECT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for S-1 Degree in Linguistics in English Department, Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Farakh Wilda Rakhmawati A2B007048 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2011 PRONOUNCEMENT The writer states truthfully that this final project is compiled by herself without taking the result from other researches in any university, in S-1, S-2, and S-3 degree and diploma. The writer also ascertains that she does not take the material from other publications or someone’s work except for the reference mentioned in bibliography. Semarang, June 2011 Farakh Wilda Rakhmawati MOTTO AND DEDICATION Life is like a book. The front cover is about the birth date and the back is the death date. Every page of the book is the day in the human life. There is a thick book and there is a thin one, but, how disheveled the front page, always there is a new page after, clean and white. Ya! Just like our life, how bad our last behavior, Allah always gives us a new day, a chance to do our best! (Anon) This final project is dedicated to my beloved family and my close friends. APPROVAL Approved by: Advisor, Dr. Ratna Asmarani, M.Ed.,M.Hum. NIP. 196102261987032001 VALIDATION Approved by Strata 1 Final Project Examination Committee Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University On October, 17th 2011 Advisor, Reader, Dr. Ratna Asmarani, M.Ed.,M.Hum. Mytha Chandria, S.S, M. A., M.A NIP. 196102261987032001 NIP. 19770118200912 2 001 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Praise to Allah SWT who has given all of His love and favor to the writer, so this project on Book Review of Matilda Written by Roald Dahl came to a completion. -

1 Character Analysis of Matilda Wormwood from Roald Dahl's

1 Character Analysis of Matilda Wormwood from Roald Dahl's Matilda Roald Dahl’s Matilda is one of the most famous children’s novels of the 20th century. The protagonist of this tale is Matilda Wormwood, a five and a half-year-old girl with a brilliant and lively mind that distances her from the rest of the family. Matilda’s character is particularly interesting as she has a powerful personality with extraordinary mental abilities, and she manages to overcome all the obstacles that surround her. The main aspect of Matilda’s personality is her particular image. From the beginning of the novel, Dahl described Matilda as exceptional person: “the child in question is extraordinary, and by that, I mean sensitive and brilliant” (1). Natov called her a rebellious superhero child with extraordinary mental strengths (140). Moreover, it is interesting that coming for the first time to the library, Matilda starts reading the book Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. This fact makes a reader assume that a great change will happen with the main character. However, Matilda is growing up surrounded by a not appreciating environment. The girl’s parents are not interested in education or literature. Her mom, Mrs Wormwood, spends afternoons playing bingo, and her dad, Mr Wormwood, is a cheater. As grotesquely described by the author, they were too involved in their “silly little lives” to understand how special their daughter is (Dahl 2). Matilda, therefore, is continually told by her parents that she is “a noisy chatterbox” and that “small girls should be seen and not heard” (Dahl 11). -

The Delightful Mr. Dahl by Jordan Thibadeaux from the Magazine Read Now!

2015-16 Grade 4-Reading-Quarter 4/Summative EN Read each selection. Then choose the best answer to each question. The fourth grade students are writing a report about Roald Dahl, a well-known author of children’s books. They gathered information from the following resources. The Delightful Mr. Dahl by Jordan Thibadeaux From the Magazine Read Now! 1 Many people discover Roald Dahl through his stories and poems. His books are translated into several languages. He has also inspired TV and radio shows and movies. With his help, kids all over the world imagine strange candies, friendly giants, and awful villains. Indeed, Roald Dahl led a life full of adventure. Yet, he had other interests, too. More Than Just Words: The Roald Dahl Foundation 2 Roald Dahl became interested in helping people who had serious injuries and diseases. As a writer, Roald cared about helping children read more. To carry out these goals, his family set up the Roald Dahl Foundation. The foundation helps people, hospitals, and charities by giving money for medical and educational needs. It continues the spirit of giving that Roald Dahl expressed throughout his life. Stories For All Ages: The Roald Dahl Museum and Story Center 3 Roald Dahl’s widow, Felicity Dahl, wanted to set up a central place to protect all of Roald’s writings. She helped create the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Center in Buckinghamshire, England. It holds a collection of Roald’s writings and recordings for the public to review. His personal letters and postcards are found there, as well as photographs and many of his awards. -

For Everyone to Read Matildabetween Roald Dahl Day – 13 September

PUFFIN BOOKS PRESENTS ASSEMBLY PACK The Mission: for everyone to read Matilda between Roald Dahl Day – 13 September – and the opening of the RSC’s Matilda: A Musical on 9 November. Here’s how your school can get involved. ‘What d’you want a flaming book for? We’ve got a lovely telly with a twelve-inch screen and now you come asking for a book!’ From 1 Welcome to the ASSEMBLY PACK! Dear Teacher Puffin Books is delighted to present this pack of resources to help you put on an engaging and educational assembly around Roald Dahl’s classic children’s book, Matilda. We’ve produced this pack to celebrate two big events: 1 It’s Roald Dahl Day on 13 September, the worldwide celebration of the author’s birthday – but you can celebrate the World’s No. 1 Storyteller any time throughout September 2 Matilda, A Musical opens at the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Courtyard Theatre in Stratford-upon- Avon, running from 9 November 2010 – 30 January 2011 These occasions make this the ideal time to celebrate the wonderful world of Roald Dahl and his characters! And with its promotion of the joys of reading and positive messages for children who are unhappy at home or school, Matilda is the perfect book to promote and discuss. Plus, of course, it’s a hugely entertaining story that has enthralled millions of children, written with all of Roald Dahl’s trademark humour and empathy. To get you started on a great Matilda-themed assembly, you will find in this pack: l A plan for a 20-minute assembly session l A short extract from Matilda that can be dramatised by -

Matilda Wormwood” - Female, 8-13 an Imaginative Girl Who Is Clever and Wise Far Beyond Her Years

Matilda the Musical Character Descriptions All characters use some form of British accent. “Matilda Wormwood” - Female, 8-13 An imaginative girl who is clever and wise far beyond her years. She has a thirst for learning that cannot be quenched. Likable and charismatic, not annoying or pretentious. Honest and unassuming, but with a prankster streak and a strong sense of justice. Must be a very strong singer and actress, equally. Strong dancing skills preferred but not required. Vocal range top: D5 Vocal range bottom: A3 “Miss Agatha Trunchbull” - Male or Female, 13-18 The tyrannical headmistress at Matilda's school who despises children. Male in female clothing/makeup/hair, or female. A cruel and sadistic person, but not a brute or brash - rather, sly and conniving, cunning and slinky. Above all, must be a strong actor with a good sense of physicality and characterization. Strong singer and dancer preferred. Vocal range top: G4 Vocal range bottom: A2 “Miss Jennifer Honey” - Female, 13-18 Matilda's kindhearted teacher. She is tired of living in fear under Miss Trunchbull. Sweet, honest, caring, and intelligent, Miss Honey is timid but willing to become brave and stand up to bullies in order to protect her students. Must be a lovely, strong singer and a strong enough actor to make the role truly compelling. Vocal range top: D5 Vocal range bottom: F3 “Mr. Wormwood” - Male, 13-18 Matilda's uncaring father. A slimy, greedy used-car salesman, unintentionally hilarious. Must be a VERY strong actor and comedian; improv and dance skills preferred. Must also be a relatively strong singer. -

FACT SHEET Roald Dahl's Matilda the Musical

FACT SHEET Roald Dahl’s Matilda the Musical Book by Dennis Kelly Music and Lyrics by Tim Minchin Based on the book Matilda by Roald Dahl Music Direction by Christopher Youstra Choreographed by Byron Easley Directed by Peter Flynn CAST ROLE ACTOR Mrs. Phelps Rayanne Gonzales* Doctor Jay Frisby* Mrs. Wormwood Tracy Lynn Olivera* Mr. Wormwood Christopher Michael Richardson* Matilda Emiko Dunn* Michael Wormwood Michael J. Mainwaring* Miss Honey Felicia Curry* The Escapologist Connor James Reilly* The Acrobat Quynh-My Luu* Miss Trunchbull Tom Story* Rudolpho Andre Hinds* Sergei Jay Frisby* Other parts played by Michelle E. Carter, Jay Frisby*, Ashleigh King*, Quynh-My Luu* , Michael J. Mainwaring*, Calvin Malone, Connor James Reilly*, Camryn Shegogue Bruce Patrick Ford, Jack St. Pierre Lavender Ainsley Deegan, Camiel Warren-Taylor Nigel Kai Mansell, Hudson Prymak Amanda Nina Brothers, Ellie Coffey Eric Sebastian Gervase, Sawyer Makl Hortensia Ella Coulson, Eliza Prymak Swings Tiziano D’Affuso, Hailey Ibberson CREATIVE TEAM Director Peter Flynn+ Choreographer Byron Easley+ Music Director Christopher Youstra^ Scenic Designer Milagros Ponce de León^^ Costume Designer Pei Lee Lighting Designer Nancy Schertler^^ Sound Designer Roc Lee Projections Designer Clint Allen^^ Wig Designer Ali Pohanka Dialect Coach Zach Campion New York Casting Pat McCorkle, CSA Katja Zarolinski, CSA McCorkle Casting Ltd. Assistant Stage Manager Rebecca Silva* Production Stage Manager John Keith Hall* *Member Actors’ Equity Association + Member Stage Directors and Choreographers Society **Member United Scenic Artists Local USA 829 ^ Olney Theatre Center Artistic Associate Press Opening: Thursday, June 27, 2019 at 8:00 pm Regular performances are Wednesday-Saturday at 8:00 pm; matinees on Saturday and Sunday at 2:00 pm; and Wednesday matinees at 2:00 pm on June 26, July 10, and 17. -

Matilda the Musical Study Guide

Study Guide New Stage Theatre Education Drew Stark, Education Associate New Stage Theatre Education Study Guide: Roald Dahl’s Matilda the Musical Table of Contents Theatre Etiquette 2 Theatre Etiquette Questions and Activity 3 Objectives and Discussion Questions 4-5 Classroom Activities 6-7 What Did She Say? Vocabulary Terms 8 Activity: Standing Up for What is Right 9 Science Corner: Facts about Newts and Coloring Page 10 Meet “Newt”: Coloring Page and Writing Activity 11 Synopsis 12-13 Bullying 14 The Cast and Character Descriptions 15 Technical Elements of New Stage’s Matilda the Musical 16-17 About the Creative Team of Matilda the Musical 18 A Brief Biography of Roald Dahl 19 Inspirational Quotables of Roald Dahl’s Matilda 20 Teacher Evaluation 21 Student Evaluation 22 **Please note: We want to hear from you and your students! Please respond by filling out the enclosed evaluation forms. These forms help us to secure funding for future Education programming. Please send your comments and suggestions to: New Stage Education Department, 1100 Carlisle Street, Jackson, MS 39202, or email: [email protected]** Thank you for your support! Page | 1 New Stage Theatre: Season 54: A Literary Party New Stage Theatre Education Study Guide: Roald Dahl’s Matilda the Musical Theatre Etiquette To best prepare your students for today’s performance, we ask that you review these guidelines for expected behavior of an audience BEFORE the show. TEACHERS: Speaking to your students about theatre etiquette is ESSENTIAL. This performance of Roald Dahl’s Matilda the Musical at New Stage Theatre may be some students’ first theatre experience. -

Matilda the Musical Character Descriptions

MATILDA THE MUSICAL Inspired by the twisted genius of Roald Dahl, the Tony Award-winning Roald Dahl's Matilda The Musical is the captivating masterpiece from the Royal Shakespeare Company that revels in the anarchy of childhood, the power of imagination and the inspiring story of a girl who dreams of a better life. With book by Dennis Kelly and original songs by Tim Minchin, Matilda has won 47 international awards and continues to thrill sold-out audiences of all ages around the world. Matilda is a little girl with astonishing wit, intelligence and psychokinetic powers. She's unloved by her cruel parents but impresses her schoolteacher, the highly loveable Miss Honey. Over the course of her first term at school, Matilda and Miss Honey have a profound effect on each other's lives, as Miss Honey begins not only to recognize but also appreciate Matilda's extraordinary personality. Matilda's school life isn't completely smooth sailing, however – the school's mean headmistress, Miss Trunchbull, hates children and just loves thinking up new punishments for those who don't abide by her rules. But Matilda has courage and cleverness in equal amounts, and could be the school pupils' saving grace! Packed with high-energy dance numbers, catchy songs and an unforgettable star turn for a young actress, Matilda is a joyous girl power romp. Children and adults alike will be thrilled and delighted by the story of the special little girl with an extraordinary imagination. CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS MATILDA The title character of the story. She MUST be as SMALL as possible. -

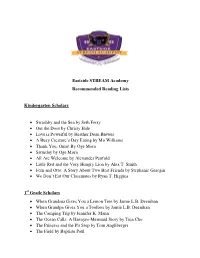

Eastside STREAM Academy Recommended Reading Lists

Eastside STREAM Academy Recommended Reading Lists Kindergarten Scholars Swashby and the Sea by Seth Ferry Out the Door by Christy Hale Love is Powerful by Heather Dean Brewer A Busy Creature’s Day Eating by Mo Williams Thank You, Omu! By Oge Mora Saturday by Oge Mora All Are Welcome by Alexander Penfold Little Red and the Very Hungry Lion by Alex T. Smith Fern and Otto: A Story About Two Best Friends by Stephanie Graegin We Don’t Eat Our Classmates by Ryan T. Higgins 1st Grade Scholars When Grandma Gives You a Lemon Tree by Jamie L.B. Deenihan When Grandpa Gives You a Toolbox by Jamie L.B. Deenihan The Camping Trip by Jennifer K. Mann The Ocean Calls: A Haenyeo Mermaid Story by Tina Cho The Princess and the Pit Stop by Tom Angliberger The Field by Baptiste Paul You Hold Me Up by Monique Gray Smith Dear Dragon: A Pen Pal by Josh Funk It Came in the Mail by Ben Clanton Julian Is a Mermaid by Jessica Love Julian at the Wedding by Jessica Love 2nd Grade Scholars My Papi has a Motorcycle by Isabel Quintero If You Come to Earth by Sophie Blackall Your Name is a Song by Jamilah Thompson Bigelow Norman: One Amazing Goldfish by Kelly Bennett Khalil and Mr. Hagerty and the Backyard Treasures by Tricia Springstubb Ten Ways to Hear Snow by Cathy Camper Giraffe Problems by Jory John The Patchwork Bik by Maxine Beneba Clarke Fruit Bowl by Mark Hoffman Interrupting Chicken and the Elephant of Surprise by David Ezra Jack (Not Jackie) by Erica Silverman I’m New Here by Anne Sibley O’Brien Someone New by Anne Sibley O’Brien 3rd Grade Scholars Pages & Co. -

Roald Dahl Guide 6-22-09.Indd

Welcome to the scrumdiddlyumPtious World of C e le br at e R oa ld D r! ahl mbe Month this Septe Puffi n Books • A division of Penguin Young Readers Group www.penguin.com/teachersandlibrarians • www.roalddahl.com Illustrations © Quentin Blake (bundles of 10) 978-0-14-241622-8 S Celebrate Month in September! e MONDAYMONDAY TUESDAYT WEDNESAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SSATAT. SUNSUN Don’t be a Twit— Channel your inner Matilda Decorate a “golden ticket” Devise your own revolting p join the Roald Dahl Club and read a wonderful book party invi tation in advance recipes—a splendiferous on roalddahl.com today. Designate a special of your Roald Dahl Day way to learn measurements table in your celebration. and numbers! classroom library as “Matilda’s Favorite Books.” t 1 2 3 4 5/6 Have a laborious day— Give everyone a great big Catch dreams like the BFG! Don’t forget to plan for the Have a fantastic day . just kidding, smile today . Don’t be You can make a dreamcatcher community service project and visit we’re swizzfiggling you! like The Twits, whose ugly from some string tied tightly on page 9 of this booklet! FantasticMrFoxMovie.com e thoughts grew upon across a hoop. Decorate it to see the latest news on the LABOR DAY them year by year. with feathers, foil, buttons— movie version of Fantastic anything that would attract Mr. Fox. Today is pleasant dreams! Roald Dahl’s birthday! 7 8 9 10 11 12/13 m In honor of Roald Dahl’s If the power of Take a trip to the library, Decorate the bookmarks on Creativity is the most birthday yesterday, host a The Magic Finger one of Matilda’s favorite page 4 of this booklet to mark marvelous medicine Roald Dahl Day party could help you swap places places—and read a your place in the whimsical to cure boredom. -

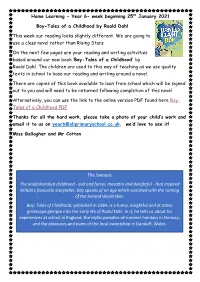

Week Beginning 25Th January 2021 Boy-Tales of a Childhood by Roald

Home Learning - Year 6- week beginning 25th January 2021 Boy-Tales of a Childhood by Roald Dahl This week our reading looks slightly different. We are going to use a class novel rather than Rising Stars. On the next few pages are your reading and writing activities based around our new book ‘Boy-Tales of a Childhood’ by Roald Dahl. The children are used to this way of teaching as we use quality texts in school to base our reading and writing around a novel. There are copies of this book available to loan from school which will be signed out to you and will need to be returned following completion of this novel. Alternatively, you can use the link to the online version PDF found here Boy- Tales of a Childhood PDF Thanks for all the hard work, please take a photo of your child’s work and email it to us on [email protected], we’d love to see it! Miss Gallagher and Mr Cotton The Synopsis The unadulterated childhood - sad and funny, macabre and delightful - that inspired Britain's favourite storyteller, Boy speaks of an age which vanished with the coming of the Second World War. Boy: Tales of Childhood, published in 1984, is a funny, insightful and at times grotesque glimpse into the early life of Roald Dahl. In it, he tells us about his experiences at school in England, the idyllic paradise of summer holidays in Norway, and the pleasures and pains of the local sweetshop in Llandaff, Wales. Task 1- Before reading, look at the the 4 different front covers and write about what you can see, infere and wonder about the book. -

Recommended Reading

Recommended Reading 1. An English-English Dictionary - the first book you should buy in Chicago. Buy one. Now. Very Easy-to-Easy (Fiction/ Novels): Fiction featuring child characters 2. The House on Mango Street by Sandra Cisneros- set in Chicago; easy-to-read with short chapters 3. The Little Prince by Antoine de Saint-Exupery- a timeless classic by a famous French author 4. Holes by Louis Sachar-young kids find an adventure after digging holes for punishment 5. Esperanza Rising by Pam Munoz Ryan-deals with Mexican immigration 6. The Pigman by Paul Zindel- two young people learn to appreciate life from an old man 7. Frannie and Zooey by J.D. Salinger- the story of a young brother and sister 8. Superfudge by Judy Blume-a young boy’s adventures and troubles; a very funny book 9. The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian by Sherman Alexie- a funny book with cartoons 10. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory by Roald Dahl- the inspiration of two different movies,(Johnny Depp) 11. James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl-a small orphan boy has many magical adventures 12. The Single Shard by Linda Sue Park-a story of Korean history 13. Wringer by Jerry Spinelli-a story of young boys and peer pressure 14. Bridge to Terebithia by Katherine Paterson-a sweet story about a friendship 15. The Outsiders by S.E. Hinton-a story of friendship, murder, gangs and social status 16. The Pearl by John Steinbeck-a Mexican folktale about a poor fisherman and a pearl 17.