Erme Estuary Site Conservation Statement & Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ENRR640 Main

Report Number 640 Coastal biodiversity opportunities in the South West Region English Nature Research Reports working today for nature tomorrow English Nature Research Reports Number 640 Coastal biodiversity opportunities in the South West Region Nicola White and Rob Hemming Haskoning UK Ltd Elizabeth House Emperor Way Exeter EX1 3QS Edited by: Sue Burton1 and Chris Pater2 English Nature Identifying Biodiversity Opportunities Project Officers 1Dorset Area Team, Arne 2Maritime Team, Peterborough You may reproduce as many additional copies of this report as you like, provided such copies stipulate that copyright remains with English Nature, Northminster House, Peterborough PE1 1UA ISBN 0967-876X © Copyright English Nature 2005 Recommended citation for this research report: BURTON, S. & PATER, C.I.S., eds. 2005. Coastal biodiversity opportunities in the South West Region. English Nature Research Reports, No. 640. Foreword This study was commissioned by English Nature to identify environmental enhancement opportunities in advance of the production of second generation Shoreline Management Plans (SMPs). This work has therefore helped to raise awareness amongst operating authorities, of biodiversity opportunities linked to the implementation of SMP policies. It is also the intention that taking such an approach will integrate shoreline management with the long term evolution of the coast and help deliver the targets set out in the UK Biodiversity Action Plan. In addition, Defra High Level Target 4 for Flood and Coastal Defence on biodiversity requires all operating authorities (coastal local authorities and the Environment Agency), to take account of biodiversity, as detailed below: Target 4 - Biodiversity By when By whom A. Ensure no net loss to habitats covered by Biodiversity Continuous All operating Action Plans and seek opportunities for environmental authorities enhancements B. -

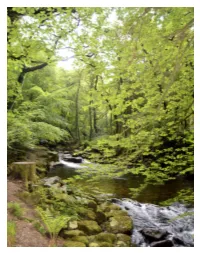

Ivybridge Pools Circular

Walk 14 IVYBRIDGE POOLS CIRCULAR The town of Ivybridge has a wonderful INFORMATION secret – a series of delightful pools above an impressive gorge, shaded by the magical DISTANCE: 3.5 miles TIME: 2-3 hours majesty of Longtimber Woods. MAP: OS Explorer Dartmoor OL28 START POINT: Harford Road Car t’s worth starting your walk with a brief pause on Park (SX 636 562, PL21 0AS) or Station Road (SX 635 566, PL21 the original Ivy Bridge, watching the River Erme 0AA). You can either park in the wind its way through the gorge, racing towards its Harford Road Car Park (three hours destination at Mothecombe on the coast. The town maximum parking) or on Station of Ivybridge owes its very existence to the river and the bridge, Road near the entrance to Longtimber Woods, by the Mill, which dates back to at least the 13th Century. While originally where there is limited free parking onlyI wide enough for pack horses, the crossing meant that the END POINT: Harford Road Car town became a popular coaching stop for passing trade between Park or Station Road Exeter and Plymouth. Interestingly the bridge is the meeting PUBLIC TRANSPORT: Ivybridge has point of the boundaries of four parishes – Harford, Ugborough, a train station on the Exeter to Plymouth line. The X38 bus Ermington and Cornwood. connects the town to both The river became a source for water-powered industry and by Plymouth and Exeter the 16th century there was a tin mill, an edge mill and a corn mill SWIMMING: Lovers Pool (SX 636 known as Glanville’s Mill (now the name of the shopping centre 570), Head Weir (SX 637 571), Trinnaman’s Pool (SX 637 572) where it once stood). -

Tin Ingots from a Probable Bronze Age Shipwreck Off the Coast of Salcombe, Devon: Composition and Microstructure

Journal of Archaeological Science 67 (2016) 80e92 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Tin ingots from a probable Bronze Age shipwreck off the coast of Salcombe, Devon: Composition and microstructure * Quanyu Wang a, , Stanislav Strekopytov b, Benjamin W. Roberts c, Neil Wilkin d a Department of Conservation and Scientific Research, the British Museum, Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3DG, UK b Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, UK c Department of Archaeology, Durham University, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK d Department of Britain, Europe and Prehistory, the British Museum, Great Russell Street, London, WC1B 3DG, UK article info abstract Article history: The seabed site of a probable Bronze Age shipwreck off the coast of Salcombe in south-west England was Received 5 November 2015 explored between 1977 and 2013. Nearly 400 objects including copper and tin ingots, bronze artefacts/ Received in revised form fragments and gold ornaments were found. The Salcombe tin ingots provided a wonderful opportunity 5 January 2016 for the technical study of prehistoric tin, which has been scarce. The chemical compositions of all the tin Accepted 8 January 2016 ingots were analysed using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and inductively Available online xxx coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES). Following the compositional analysis, micro- structural study was carried out on eight Salcombe ingots selected to cover those with different sizes, Keywords: Tin ingots shapes and variable impurity levels and also on the two Erme Estuary ingots using metallography and Bronze Age scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM-EDS). -

The Early Settlement of Hope Cove and Bolt Tail and the Part Played by Quay Sands

The Early Settlement of Hope Cove and Bolt Tail and the part played by Quay Sands A brief discussion. Introduction This short paper in no way seeks to offer a definitive account of settlement but by referring to the evidence in the landscape wishes to offer a point of view for discussion. Challenges to any assumptions are most welcome. What I have called Quay Sands may be called Pilchard Cove by some and indeed appears as such on modern maps. The central valley area of Bolt Tail runs from Redrot Cove in the south to Quay Sands in the north. The Courtney Map of 1841 calls Redrot Cove “Reed Rot” and the area between the two coves is named Reed Rot Bottom. In these notes I will refer to it as Redrot Bottom. It should be noted that the same map labels Quay Sands “Pilchard Cove”. No doubt this refers to its use during the days of the pilchard bonanza but a sketch map drawn in 1823 for a proposed new breakwater calls it Pilchard Quay. Figure 1 Early human activity on Bolt Tail and Inner Hope Figure 2 Overview Figure 3 Fortified area. Frances Griffiths, Devon County Archaeology Discussion There are a number of sixteenth century buildings in the twin villages of Inner and Outer Hope but nothing much to show for earlier habitation apart from an early mention in the Assize Rolls for 1281. The Iron Age Fort on Bolt Tail has had two comprehensive but non-invasive surveys in the last twenty years. It is considered to be of Iron Age date but Waterhouse hints that by comparing it with similar forts it may have its beginnings in the stone age. -

Waste South Hams District

PTE/19/46 Development Management Committee 27 November 2019 County Matter: Waste South Hams District: Change of use from vehicle depot (Class B8) to a waste transfer station (sui generis) including land previously used as a Household Waste Recycling Centre, with building works to include demolition of an existing storage building, and construction of a waste transfer station building and associated litter netting, Ivybridge Council Depot, Ermington Road, Ivybridge Applicant: FCC Recycling (UK) Limited Application No: 2519/19/DCC Date application received by Devon County Council: 25 July 2019 Report of the Chief Planner Please note that the following recommendation is subject to consideration and determination by the Committee before taking effect. Recommendation: It is recommended that planning permission is granted subject to the conditions set out in Appendix I this report (with any subsequent minor changes to the conditions being agreed in consultation with the Chair and Local Member). 1. Summary 1.1 This application relates to a change of use from an existing vehicle depot, together with an area of land previously used as a Household Waste Recycling Centre, to a waste transfer station, with the demolition of an existing storage building and construction of a new waste transfer building. The new facility will be used for the reception and bulking up of household recyclable waste materials. 1.2 The main material planning considerations in this case are the impacts upon local working and living conditions; impacts upon ecology and the local landscape; flooding and drainage; pollution of watercourses; the economy; and impacts on the highway and the Public Right of Way. -

South West River Basin District Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment

South West river basin district Flood Risk Management Plan 2015 to 2021 Habitats Regulation Assessment March 2016 Executive summary The Flood Risk Management Plan (FRMP) for the South West River Basin District (RBD) provides an overview of the range of flood risks from different sources across the 9 catchments of the RBD. The RBD catchments are defined in the River Basin Management Plan (RBMP) and based on the natural configuration of bodies of water (rivers, estuaries, lakes etc.). The FRMP provides a range of objectives and programmes of measures identified to address risks from all flood sources. These are drawn from the many risk management authority plans already in place but also include a range of further strategic developments for the FRMP ‘cycle’ period of 2015 to 2021. The total numbers of measures for the South West RBD FRMP are reported under the following types of flood management action: Types of flood management measures % of RBD measures Prevention – e.g. land use policy, relocating people at risk etc. 21 % Protection – e.g. various forms of asset or property-based protection 54% Preparedness – e.g. awareness raising, forecasting and warnings 21% Recovery and review – e.g. the ‘after care’ from flood events 1% Other – any actions not able to be categorised yet 3% The purpose of the HRA is to report on the likely effects of the FRMP on the network of sites that are internationally designated for nature conservation (European sites), and the HRA has been carried out at the level of detail of the plan. Many measures do not have any expected physical effects on the ground, and have been screened out of consideration including most of the measures under the categories of Prevention, Preparedness, Recovery and Review. -

Rockcliffe, Hope Cove Kingsbridge, TQ7 3HG

stags.co.uk 01548 853131 | [email protected] Rockcliffe, Hope Cove Kingsbridge, TQ7 3HG Just 200 yards from the beach in this delightful South Hams village, a detached property with fine sea and coastal views. • Just yards from the beach • 19' dual aspect sitting room • 24' triple aspect kitchen/dining room • 4 bedrooms (two en-suite) • West-facing deck • Easily- managed gardens • Garage, and ample additional parking for boat etc • • Guide price £595,000 Cornwall | Devon | Somerset | Dorset | London Rockcliffe, Hope Cove, Kingsbridge, TQ7 3HG SITUATION AND DESCRIPTION: A light and airy dual aspect room with views to the sea and With its pretty, thatched cottages and beautiful sandy beaches, surrounding coastline and patio doors leading to the DECK. Hope Cove is a quintessential Devon fishing village. Once a Gazco coal-effect burner. Matching pine flooring. Archway favourite haunt for smugglers, it now has a thriving local through to: community with a shop/post office, village Inn, numerous small OPEN-PLAN KITCHEN/DINING ROOM: restaurants and good hotels. It also provides facilities for launching and mooring small craft. A triple aspect room with views to the sea from the dining The sailing Mecca of Salcombe is within easy reach, either on area. Kitchen area well-fitted with a good range of cupboards, foot or by road , as are Thurlestone, with its superb golf course units and drawers and one and a half bowl single drainer sink and Kingsbridge, with its excellent shopping and leisure unit with mixer tap. Oil-fired Rayburn range cooker. Larder facilities. The village is on the Coastal Footpath and is cupboard. -

Slipping Through The

Contents Acknowledgements 2 Executive Summary 3 Section 1: Introduction 4 1.1 Statement of IFA MAG Position 4 1.1.1 Archaeological Archives 4 1.1.2 Maritime Archaeological Archives 5 1.2 Structure of Strategy Document 6 1.3 Case Study: An Illustration of the Current Situation 7 Section 2: The Current System 9 2.1 The Current System in Policy: Roles and Responsibilities 9 2.1.1 Who’s Who? 9 2.1.2 Roles and Responsibilities 11 2.1.3 Legislative Responsibilities 12 2.2 The Current System in Practice 13 2.2.1 The Varied Fate of Protected Wreck Site Archives 13 2.2.2.The Unprotected Majority of Britain’s Historic Wreck Sites 15 2.3 A question of resources, remit or regulation? 16 Section 3: Archival Best Practice and Maritime Issues 17 3.1 Established Archival Policy and Best Practice 17 3.2 Application to Maritime Archives 18 3.2.1 Creation—Management and Standards 18 3.2.2 Preparation—Conservation, Selection and Retention 19 3.2.3 Transfer—Ownership and Receiving Museums 20 3.2.4 Curation—Access, Security and Public Ownership 21 3.3 Communication and Dialogue 22 3.4 Policy and Guidance Voids 23 Section 4: Summary of Issues 24 4.1.1 Priority Issues 24 4.1.2 Short Term Issues 24 4.1.3 Long Term Issues 24 4.2 Conclusions 25 Section 5: References 26 Section 6: Stakeholder and Other Relevant Organisations 27 Section 7: Policy Statements 30 IFA Strategy Document: Maritime Archaeological Archives 1 Acknowledgements This document has been written by Jesse Ransley and edited by Julie Satchell on behalf of the Institute of Field Archaeologists Maritime Affairs Group. -

Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites Annual Report 2009 (April 2009 - March 2010)

Department for Culture, Media and Sport Architecture and Historic Environment Division Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites Annual Report 2009 (April 2009 - March 2010) Compiled by English Heritage for the Advisory Committee on Historic Wreck Sites. Text was also contributed by Cadw, Historic Scotland and the Environment and Heritage Service, Northern Ireland. s e vi a D n i t r a M © Contents ZONE ONE – Wreck Site Maps and Introduction UK Designated Shipwrecks Map ......................................................................................3 Scheduled and Listed Wreck Sites Map ..........................................................................4 Military Sites Map .................................................................................................................5 Foreword: Tom Hassall, ACHWS Chair ..........................................................................6 ZONE TWO – Case Studies on Protected Wreck Sites The Swash Channel, by Dave Parham and Paola Palma .....................................................................................8 Archiving the Historic Shipwreck Site of HMS Invincible, by Brandon Mason ............................................................................................................ 10 Recovery and Research of the Northumberland’s Chain Pump, by Daniel Pascoe ............................................................................................................... 14 Colossus Stores Ship? No! A Warship Being Lost? by Todd Stevens ................................................................................................................ -

Crown Buildings, Soar LOCATION

FOR SALE Crown Buildings, Soar LOCATION Situated in an elevated position inland from Bolt Head the site overlooks the sea and estuary at Salcombe and East Portlemouth within an area of outstanding natural beauty. The site adjoins the former RAF Bolt Head, which is now a privately run airfield. Salcombe is famous for its picturesque situation and is considered one of the most popular holiday destination towns in South Devon. The town boasts superb coastal views and is situated in the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The villages of Malborough 1.5 miles) and Hope Cove (2.5 miles) are also close by and Kingsbridge is approximately 5.4 miles. Surrounded by farmland and with open coastal views the location is both scenic and dramatic. The Crown Building is positioned to the South East corner of the plot which measures 1.12 hectares (2.77 acres) with a private access road of approximately 1.5 km providing a further 0.5 hectares/1.23 acres. HISTORY The Crown Building as it is now named has had a number of uses over the years and the structure that stands today was mostly completed in 1954 as a part of an Air Ministry ROTOR program. What was originally called the Hope Cove R6 Control Bunker, it’s purpose was as a RADAR control station built underground to withstand attack from the air. It was active until 1957 after which time it was briefly used as an RAF fighter control school until transfer to the Home Office in 1958. Home Office use was as a Regional seat of Government that would control the South West in the event of nuclear war and was maintained for this purpose until closure in the early 1990’s. -

Black's Guide to Devonshire

$PI|c>y » ^ EXETt R : STOI Lundrvl.^ I y. fCamelford x Ho Town 24j Tfe<n i/ lisbeard-- 9 5 =553 v 'Suuiland,ntjuUffl " < t,,, w;, #j A~ 15 g -- - •$3*^:y&« . Pui l,i<fkl-W>«? uoi- "'"/;< errtland I . V. ',,, {BabburomheBay 109 f ^Torquaylll • 4 TorBa,, x L > \ * Vj I N DEX MAP TO ACCOMPANY BLACKS GriDE T'i c Q V\ kk&et, ii £FC Sote . 77f/? numbers after the names refer to the page in GuidcBook where die- description is to be found.. Hack Edinburgh. BEQUEST OF REV. CANON SCADDING. D. D. TORONTO. 1901. BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/blacksguidetodevOOedin *&,* BLACK'S GUIDE TO DEVONSHIRE TENTH EDITION miti) fffaps an* Hlustrations ^ . P, EDINBURGH ADAM AND CHARLES BLACK 1879 CLUE INDEX TO THE CHIEF PLACES IN DEVONSHIRE. For General Index see Page 285. Axniinster, 160. Hfracombe, 152. Babbicombe, 109. Kent Hole, 113. Barnstaple, 209. Kingswear, 119. Berry Pomeroy, 269. Lydford, 226. Bideford, 147. Lynmouth, 155. Bridge-water, 277. Lynton, 156. Brixham, 115. Moreton Hampstead, 250. Buckfastleigh, 263. Xewton Abbot, 270. Bude Haven, 223. Okehampton, 203. Budleigh-Salterton, 170. Paignton, 114. Chudleigh, 268. Plymouth, 121. Cock's Tor, 248. Plympton, 143. Dartmoor, 242. Saltash, 142. Dartmouth, 117. Sidmouth, 99. Dart River, 116. Tamar, River, 273. ' Dawlish, 106. Taunton, 277. Devonport, 133. Tavistock, 230. Eddystone Lighthouse, 138. Tavy, 238. Exe, The, 190. Teignmouth, 107. Exeter, 173. Tiverton, 195. Exmoor Forest, 159. Torquay, 111. Exmouth, 101. Totnes, 260. Harewood House, 233. Ugbrooke, 10P. -

Coastal Towns

House of Commons ODPM: Housing, Planning, Local Government and the Regions Committee Coastal Towns Session 2005–06 Volume II: Written Evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 27 March 2006 HC 1023-II Published on 18 April 2006 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £18.50 The ODPM: Housing, Planning, Local Government and the Regions Committee The ODPM: Housing, Planning, Local Government and the Regions Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister and its associated bodies. Current membership Dr Phyllis Starkey MP (Labour, Milton Keynes South West) (Chair) Sir Paul Beresford MP (Conservative, Mole Valley) Mr Clive Betts MP (Labour, Sheffield Attercliffe) Lyn Brown MP (Labour, West Ham) John Cummings MP (Labour, Easington) Greg Hands MP (Conservative, Hammersmith and Fulham) Martin Horwood MP (Liberal Democrats, Cheltenham) Anne Main MP (Conservative, St Albans) Mr Bill Olner MP (Labour, Nuneaton) Dr John Pugh MP (Liberal Democrats, Southport) Alison Seabeck MP (Labour, Plymouth, Devonport) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on