Polish/American Heritage Conservation Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Field Trip Guidebook

FIELD TRIP GUIDEBOOK Edited by Ewa Głowniak, Agnieszka Wasiłowska IX ProGEO Symposium Geoheritage and Conservation: Modern Approaches and Applications Towards the 2030 Agenda Chęciny, Poland 25-28th June 2018 FIELD TRIP GUIDEBOOK Edited by Ewa Głowniak, Agnieszka Wasiłowska This publication was co-financed by Foundation of University of Warsaw and ProGEO – The European Association for the Conservation of the Geological Heritage Editors: Ewa Głowniak, Agnieszka Wasiłowska Editorial Office: Faculty of Geology, University of Warsaw, 93 Żwirki i Wigury Street, 02-089 Warsaw, Poland Symposium Logo design: Łucja Stachurska Layout and typesetting: Aleksandra Szmielew Cover Photo: A block scree of Cambrian quartzitic sandstones on the slope of the Łysa Góra Range – relict of frost weathering during the Pleistocene. Photograph by Peter Pervesler Example reference: Bąbel, M. 2018. The Badenian sabre gypsum facies and oriented growth of selenite crystals. In: E. Głow niak, A. Wasiłowska (Eds), Geoheritage and Conservation: Modern Approaches and Applications Towards the 2030 Agenda. Field Trip Guidebook of the 9th ProGEO Symposium, Chęciny, Poland, 25–28th June 2018, 55–59. Faculty of Geology, University of Warsaw, Poland. Print: GIMPO Agencja Wydawniczo-Poligraficzna, Marii Grzegorzewskiej 8, 02-778 Warsaw, Poland ©2018 Faculty of Geology, University of Warsaw ISBN 978-83-945216-5-3 The content of abstracts are the sole responsibility of the authors Organised by Faculty of Geology, University of Warsaw Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy -

Decisions Adopted by the World Heritage Committee at Its 37Th Session (Phnom Penh, 2013)

World Heritage 37 COM WHC-13/37.COM/20 Paris, 5 July 2013 Original: English / French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE World Heritage Committee Thirty-seventh session Phnom Penh, Cambodia 16 - 27 June 2013 DECISIONS ADOPTED BY THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE AT ITS 37TH SESSION (PHNOM PENH, 2013) Table of content 2. Requests for Observer status ................................................................................ 3 3A. Provisional Agenda of the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee (Phnom Penh, 2013) ......................................................................................................... 3 3B. Provisional Timetable of the 37th session of the World Heritage Committee (Phnom Penh, 2013) ......................................................................................................... 3 5A. Report of the World Heritage Centre on its activities and the implementation of the World Heritage Committee’s Decisions ................................................................... 4 5B. Reports of the Advisory Bodies ................................................................................. 5 5C. Summary and Follow-up of the Director General’s meeting on “The World Heritage Convention: Thinking Ahead” (UNESCO HQs, 2-3 October 2012) ............................. 5 5D. Revised PACT Initiative Strategy............................................................................ 6 5E. Report on -

2019-2020 World Heritage

4 T rom the vast plains of the Serengeti to historic cities such T 7 as Vienna, Lima and Kyoto; from the prehistoric rock art 1 ICELAND 5 3 on the Iberian Peninsula to the Statue of Liberty; from the 2 8 Kasbah of Algiers to the Imperial Palace in Beijing — all 5 2 of these places, as varied as they are, have one thing in common. FINLAND O 3 All are World Heritage sites of outstanding cultural or natural 3 T 15 6 SWEDEN 13 4 value to humanity and are worthy of protection for future 1 5 1 1 14 T 24 NORWAY 11 2 20 generations to know and enjoy. 2 RUSSIAN 23 NIO M O UN IM D 1 R I 3 4 T A FEDERATION A L T • P 7 • W L 1 O 17 A 2 I 5 ESTONIA 6 R D L D N 7 O 7 H 25 E M R 4 I E 3 T IN AG O 18 E • IM 8 PATR Key LATVIA 6 United Nations World 1 Cultural property The designations employed and the presentation 1 T Educational, Scientific and Heritage of material on this map do not imply the expres- 12 Cultural Organization Convention 1 Natural property 28 T sion of any opinion whatsoever on the part of 14 10 1 1 22 DENMARK 9 LITHUANIA Mixed property (cultural and natural) 7 3 N UNESCO and National Geographic Society con- G 1 A UNITED 2 2 Transnational property cerning the legal status of any country, territory, 2 6 5 1 30 X BELARUS 1 city or area or of its authoritiess. -

Destination UPDATE POLAND

destination UPDATE POLAND Poland is situated in Central Europe between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathian Mountains and borders with Germany, Czech Republic, Slovakia and a number of former Russian countries. Poland is over 1000 years old and in its early history was a monarchy. Latterly, due to invasion, it became a communist country but since 1989 it has transformed into a democracy with a fully active market economy. In addition, Poland has recently joined the European Union. From an incentive and conference point of view it is a new destination, but has the necessary infrastructure and knowledge to successfully handle this type of business. Much of this is due to companies like MAZURKAS TRAVEL, our recommended DMC in Poland, who have pioneered much of what is on offer and who have fine-tuned the services required to offer you and your clients the best possible service. Like all relatively new democracies, shaking off the shackles of previous systems takes time and bureaucracy can be a bit unwieldy, but with companies like MAZURKAS TRAVEL attitudes are changing fast. The future potential for the EUR 2012 has had a huge impact on infrastructure in Warsaw and currently there is estima ted about 50.000 beds at hotels and improved motorway systems etc. Hotels in Warsaw are also great value for money, with competitive rates for a room at a 5-star hotel cost ing you around 100 – 200 EUR per room/day depending on season. There are also full-day conference packages, which include two coffee breaks and lunch costing from about 70 EUR per day. -

Tourist Information

TOURIST INFORMATION E DZIEDZ W IC TO T IA W W O • ´S • W L O A I R D L D N H O E M R I E T IN AG O E • PATRIM United Nations Old City of Zamość Educational, Scientific and inscribed on the World Cultural Organization Heritage List in 1992 Organizacja Narodów Stare Miasto w Zamościu Zjednoczonych wpisane na Listę Światowego dla Wychowania, Dziedzictwa w roku 1992 Nauki i Kultury free copy Jan Sariusz Zamoyski a humanist, patron of arts, specialist in languages and orator. He was born on 19 March 1542 in Skokówka, near Zamość and died on 3 June 1605. First he was King Sigismund Augustus’s Secretary, in 1576 he was granted the title of the Great Crown Chancellor Akt lokacyjny Zamościa z 12 czerwca 1580 r. and in 1578 that of the Great Zbiory Muzeum Zamojskiego. Crown Hetman. He was also an advisor to King Sigismund II Augustus and King Stefan Batory. ZAMOŚĆ: historically Zamość is an ideal town, built on an anthropomorphic plan. Hetman’s residence is the head, the Zamojska Academy and the Collegiate Church are the lungs and Grodzka Bernardo Morando Street running across the Rynek Wielki to the Lwowska Gate is the spine. an Italian architect who Zamość was set up by Chancellor and Great Crown Hetman Jan Zamoyski, one of the was born in 1540 in Padua, most outstanding people in 16th century Poland. Italy and died in 1600 On 10 April 1580 King Stefan Batory granted the town its municipal rights and a coat in Zamość. -

Adoption of Retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value

World Heritage 38 COM WHC-14/38.COM/8E Paris, 30 April 2014 Original: English / French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty-eighth session Doha, Qatar 15 – 25 June 2014 Item 8 of the Provisional Agenda: Establishment of the World Heritage List and of the List of World Heritage in Danger 8E: Adoption of Retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value SUMMARY This Document presents a Draft Decision concerning the adoption of 127 retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value submitted by 50 States Parties for properties which had no Statement of Outstanding Universal Value approved at the time of their inscription on the World Heritage List. The annex contains the full text of the retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value concerned in the original language submitted. Draft Decision: 38 COM 8E, see Point II. I. BACKGROUND 1. The concept of Statement of Outstanding Universal Value as an essential requirement for the inscription of a property on the World Heritage List was introduced in the Operational Guidelines in 2005. All properties inscribed since 2007 present such a Statement. 2. In 2007, the World Heritage Committee in its Decision 31 COM 11D.1 requested that Statements of Outstanding Universal Value be drafted and approved retrospectively for all World Heritage properties inscribed between 1978 and 2006, prior to the launch of the Second Cycle of Periodic Reporting in each region. 3. As a consequence, in the framework of the Periodic Reporting exercise, States Parties are drafting retrospective Statements of Outstanding Universal Value for World Heritage properties located within their territories which are afterwards reviewed by the relevant Advisory Bodies. -

Ref: CL/WHC/14/02 27 November 2002 To

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'éducation, la science et la culture 7, place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris 07 SP Tel. : + 33 (0) 1.45.68.15.71 Fax : + 33 (0) 1.45.68.55.70 Ref: CL/WHC/14/02 27 November 2002 To: Permanent Delegations, Observer Missions and National Commissions of States Parties to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention in Europe and North America Madam/Sir, Subject: Periodic Reporting on the application of the World Heritage Convention and on the state of conservation of World Heritage properties in Europe and North America I have the honor to draw your attention to Article 29 of the 1972 UNESCO World Heritage Convention which requests that “The States Parties to this Convention shall, in the reports which they submit to the General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (…), give information on the legislative and administrative provisions which they have adopted and other action which they have taken for the application of this Convention, together with details of the experience acquired in this field”. The twenty-ninth General Conference of UNESCO in 1997, requested the World Heritage Committee to define the periodicity, form, nature and extent of the periodic reporting on the application of the World Heritage Convention and on the state of conservation of World Heritage properties and to examine and respond to these reports. The World Heritage Committee, at its twenty-second session in December 1998, decided to invite States Parties to the World Heritage Convention to submit the periodic reports every six years in accordance with the Format for periodic reports as adopted by the Committee. -

Visit to Auschwitz Birkenau: a Rite of Passage for Modern Man

UNESCO PUBLISHING WORLD HERITAGE No. 84 xxxxxxxxx. editorial T xxxxxxxxxx. Cover: XXXXXXXXXXXX Mechtild Rössler Director of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre Special Issue Special message Special Message By Prof Dr habil. Piotr Gliński Deputy Prime Minister Minister of Culture and National Heritage of Poland © xxx NESCO was born of the most tragic As many as 14 sites representing the diversity and richness experiences suffered by Europe and the of Polish culture and history have been identified as worthy of world. The Second World War cost millions recognition for their Outstanding Universal Value. The sites on of human lives and led to the loss of vast the World Heritage List in Poland include Krakow, a city with cultural resources and the annihilation an unbroken continuity of material culture, and Warsaw’s of entire cities. It was at that time the idea began to emerge reconstructed historic Old Town with the Royal Castle. The that “since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of beauty of historic Krakow and the power of Warsaw reborn men that the defences of peace must be constructed”, which from the ashes are two important components of Polish identity. was subsequently included in the Preamble to the UNESCO UNESCO’s Memory of the World International Register also Constitution. Poland was among the founding states of the comprises the archives of the Warsaw Reconstruction Office set up new organization and soon joined in its activities. Looking from after the war. In today’s world, marked by the tragedy of Aleppo behind the ‘Iron Curtain’, Poles saw UNESCO as a window onto and the plight of Palmyra, the reconstruction of Warsaw and the world and a platform for the exchange of ideas as well as contacts with other countries. -

One Ideology, Two Visions. Churches And

1 Leibniz Institut für Geschichte und Kultur des östlichen Europa, Leipzig, April 2019. ONE IDEOLOGY, TWO VISIONS. CHURCHES AND THE SOCIALIST CITY, EAST BERLIN AND WARSAW – 1945-1975. By Marcus van der Meulen. In this presentation sacred architecture in rebuilding war damaged cities during the the period 1945-1975 is discussed, starting with a short look at the postwar reconstruction of Minsk and Magdeburg as socialist cities, followed by a look at East Berlin and Warsaw. This presentation is an adapted version of the paper presented at the conference State (Re)construction in Art in Central and Eastern Europe 1918-2018 in Warsaw 2018. We will look at the first three decades of rebuilding the nation after the end of the Second World War. 1975 was a pivotal year. It was the European Architectural Heritage Year, shifting the heritage values regarding religious buildings from the traditional religious connotations towards the important values of education and economy, including tourism, and the year the German Democratic Republic adopted the Denkmalschutz Gesetz in the DDR, heralding a change, a growing awareness of the significance of historic buildings including sacred architecture. Introduction. At the end of the Second World War in May 1945 two capitals were in ruins. The war had destroyed much of Europe. Cities and towns had been bombed or damaged in combat. Some buildings were even calculatedly dynamited and burned down. As the Nazis retreated historic buildings, in my home country especially the church towers, were targeted and detonated. Severe combat damaged the German capital until the final days of the war. -

AIRFARE See Back for Details

Personalized Tours presents… FREE AIRFARE See back for details 9 DAY WORLD HOLIDAY NEW PROGRAM Pride of Poland Departure Date: October 5, 2021 Pride of Poland 9 Days • 11 Meals From Gdansk’s “Royal Way” to the longest pier in Europe; from the vibrant, historic capital of Warsaw to Kraków’s charming Old Town with its Market Square and 16th- century Cloth Hall, you’ll see it all on this Mayflower holiday. Visit historic castles, beautiful cathedrals and sites of great religious significance. And journey to Auschwitz and the Kazimierz Jewish District to gain insight into a painful period in Polish History. You’ll truly experience the Pride of Poland during this 9-day adventure. TOUR HIGHLIGHTS 4 11 Meals (7 breakfasts, 1 lunch and 3 dinners) 4 Airport transfers on tour dates when air is provided by Mayflower Cruises & Tours 4 Two nights in Gdansk Historic architecture abounds in Gdansk 4 Full-day sightseeing tour of Gdansk with visits to St. Mary’s Church and Sopot Pier 4 Visit to the Castle of the Teutonic Order of Knights in Malbork DAY 1 – Depart the USA 4 Two nights in Warsaw Depart the USA on your overnight flight to Gdansk, Poland. 4 Full-day sightseeing tour of Warsaw with visits to the Royal Castle and Wilanów Palace DAY 2 – Gdansk, Poland 4 A visit to Czstochowa to visit Jasna Góra, the most important Upon arrival, you’ll be met by a Mayflower Cruises & Tours Marian shrine in Poland representative and transferred to your hotel. The remainder of the day 4 Three nights in Kraków is free for you to relax or explore on your own. -

Unesco - World Heritage in Poland

UNESCO - WORLD HERITAGE IN POLAND Anna K Ola Cz Emilia S Auschwitz Birkenau Auschwitz was first constructed to hold Polish political prisoners, who began to arrive in May 1940. The first extermination of prisoners took place in September 1941, and Auschwitz Birkenau went on to become a major site of the Nazi Final Solution to the Jewish Question. From early 1942 until late 1944, transport trains delivered Jews to the camp's gas chambers from all over German-occupied Europe, where they were killed en masse with the pesticide Zyklon B. An estimated 1.3 million people were sent to the camp, of whom at least 1.1 million died. Around 90 percent of those killed were Jewish; approximately 1 in 6 Jews killed in the Holocaust died at the camp. Others deported to Auschwitz included 150,000 Poles, 23,000 Romani and Sinti, 15,000 Soviet prisoners of war, 400 Jehovah's Witnesses, and tens of thousands of others of diverse nationalities, including an unknown number of homosexuals. Many of those not killed in the gas chambers died of starvation, forced labor, infectious diseases, individual executions, and medical experiments. Castle of the Teutonic Order in Malbork Located in the Polish town of Malbork, is the largest castle in the world measured by land area.It was originally built by the Teutonic Knights, a German Roman Catholic religious order of crusaders, in a form of an Ordensburg fortress. The Order named it Marienburg(Mary's Castle). The town which grew around it was also named Marienburg. In 1466, both castle and town became part of Royal Prussia, a province of Poland. -

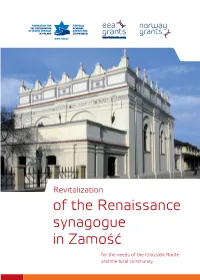

Of the Renaissance Synagogue in Zamość for the Needs of the Chassidic Route and the Local Community 3

1 Revitalization of the Renaissance synagogue in Zamość for the needs of the Chassidic Route and the local community 3 ABOUT THE FOUNDATION The Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland was founded in 2002 by the Union of Jewish Communities in Poland and the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO). The Foundation’s mission is to protect surviving monuments of Jewish heritage in Poland. Our chief task is the protection of Jewish cemeteries. In cooperation with other organizations and private donors we have saved from destruction, fenced and commemorated several burial grounds (in Zakopane, Kozienice, Mszczonów, Iwaniska, Strzegowo, Dubienka, Kolno, Iłża, Wysokie Mazow- th The official opening of the “Synagogue” Center on April 5 , 2011, was held under the honor- ieckie, Siedleczka-Kańczuga, Żuromin and several other localities). Our activities also include the ary patronage of the President of the Republic of Poland, Bronisław Komorowski. renovation and revitalization of Jewish monuments of special significance, such as the synagogues in Kraśnik, Przysucha and Rymanów as well as the synagogue in Zamość. However, the protection of material patrimony is not the Foundation’s only task. We are equally concerned about increasing public knowledge regarding the history of Polish Jews, whose contribu- This brochure has been published within the framework of the project “Revitalization of the Renaissance synagogue in tion to Poland’s heritage spans several centuries. Our most important educational projects include Zamość for the needs of the Chassidic Route and the local community” implemented by the Foundation for the Preserva- tion of Jewish Heritage in Poland and supported by a grant from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the EEA the “To Bring Memory Back” program, addressed to high school students, and POLIN – Polish Jews’ Financial Mechanism and the Norwegian Financial Mechanism.