DRAFT Protecting Shareholder and Natural Value

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BP and Rio Tinto Plan Clean Coal Project for Western Australia I P

BP and Rio Tinto Plan Clean Coal Project for Western Australia I p... http://www.bp.com/genericarticle.do?categoryId=2012968&content... Site Index | Contact us | Reports and publications | BP worldwide | Home Search: Go About BP Environment and society Products and services Investors Press Careers BP Global Press Press releases Press releases BP and Rio Tinto Plan Clean Coal Project for Western Speeches Australia Features and news Images and graphics Release date: 21 May 2007 Contact Information In this section BP and Rio Tinto today announced that they are beginning feasibility studies and work on plans for the potential BP Takes Delivery of development of a A$2 billion (US$1.5 billion) coal-fired World's Largest LNG Carrier power generation project at Kwinana in Western Australia What is RSS? BP and D1 Oils Form Joint that would be fully integrated with carbon capture and Venture to Develop Jatropha storage to reduce its emissions of greenhouse gases. This Biodiesel Feedstock will be the first new project for Hydrogen Energy, the new BP Announces Significant company launched by BP and Rio Tinto last week, subject North Sea Investment to Boost to regulatory approval. The planned project would be an UK Gas Supplies industrial-scale coal-fired power and carbon capture and storage project. It would generate enough electricity to BP, ABF and DuPont Unveil $400 Million Investment in UK meet 15 per cent of the demand of south west Western Biofuels Australia, while each year capturing and permanently storing about four million tonnes of carbon dioxide which BP and TNK-BP Plan otherwise would have been emitted to the atmosphere.The Strategic Alliance with project would gasify locally-produced coal from the Collie Gazprom as TNK-BP Sells its region to produce hydrogen and carbon dioxide. -

Men and Women Working Together for Real Change

Men and women working together for real change May 2018 30% Club . The 30% Club is a global campaign that signs up Chairs and CEOs to take action to create a better balance of men and women at all levels of their organisations as a business imperative rather than a ‘women’s issue’. The Club launched in the UK in 2010 with a target of a minimum of 30% women on FTSE-100 boards by 2015. There are circa 300 members of the UK Club and the proportion of female FTSE-100 directors has risen from 12.5% to 28.9%*. As of 2016 the scope of the above target was extended to a minimum of 30% women on FTSE-350 boards by end 2020 (currently at 25.3%*) . In tandem with the above – and in order to ensure that this 30% remains sustainable – we have also established a pipeline target of a minimum of 30% women at senior management level of FTSE-100 companies by 2020 (currently 25.2% at Executive Committee + direct report levels**). The 30% Club is becoming an international community. It complements and amplifies individual company efforts and existing initiatives through collaboration, sharing of best practice, measurable goals and joined-up actions. The 30% Club does not believe in mandatory quotas. Instead, the 30% Club is aiming for meaningful, sustainable, business- led change, as recommended by the Davies and Hampton-Alexander Reviews. Scarce representation of women at senior levels is a global phenomenon. Local 30% Clubs have been launched in the US, Hong Kong, Ireland, Southern Africa, Australia, Malaysia, Canada, Italy, the GCC and Turkey. -

Preparing for Carbon Pricing: Case Studies from Company Experience

TECHNICAL NOTE 9 | JANUARY 2015 Preparing for Carbon Pricing Case Studies from Company Experience: Royal Dutch Shell, Rio Tinto, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company Acknowledgments and Methodology This Technical Note was prepared for the PMR Secretariat by Janet Peace, Tim Juliani, Anthony Mansell, and Jason Ye (Center for Climate and Energy Solutions—C2ES), with input and supervision from Pierre Guigon and Sarah Moyer (PMR Secretariat). The note comprises case studies with three companies: Royal Dutch Shell, Rio Tinto, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E). All three have operated in jurisdictions where carbon emissions are regulated. This note captures their experiences and lessons learned preparing for and operating under policies that price carbon emissions. The following information sources were used during the research for these case studies: 1. Interviews conducted between February and October 2014 with current and former employees who had first-hand knowledge of these companies’ activities related to preparing for and operating under carbon pricing regulation. 2. Publicly available resources, including corporate sustainability reports, annual reports, and Carbon Disclosure Project responses. 3. Internal company review of the draft case studies. 4. C2ES’s history of engagement with corporations on carbon pricing policies. Early insights from this research were presented at a business-government dialogue co-hosted by the PMR, the International Finance Corporation, and the Business-PMR of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) in Cologne, Germany, in May 2014. Feedback from that event has also been incorporated into the final version. We would like to acknowledge experts at Royal Dutch Shell, Rio Tinto, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E)—among whom Laurel Green, David Hone, Sue Lacey and Neil Marshman—for their collaboration and for sharing insights during the preparation of the report. -

Severn Trent: Supporting the Green Recovery

ST Classification: UNMARKED SEVERN TRENT: SUPPORTING THE GREEN RECOVERY October 2020 ST Classification: UNMARKED Background In July 2020, the Government and regulators invited water companies to come forward with proposals to support the country's green recovery. We’re looking at how we can help support the recovery by accelerating and broadening our plans to generate real and lasting benefits for our customers, the environment and the wider economy. The following slides outline our thoughts on what the green recovery could look like in the Midlands, with the focus on the need and the potential benefits new investment could bring. We have outlined four ideas: • Idea 1 –unlock faster progress to address water scarcity in an environmentally ambitious way • Idea 2 –unlocking the potential of our rivers • Idea 3 –taking care of customer owned supply pipes (removing lead and tackling leakage) • Idea 4 –transform flooding from a devasting problem into a shared natural asset These ideas go beyond our usual remit and are looking to identify opportunities to work with other organisations to support our communities through an improved environment and prosperity for current and future generations. ST Classification: UNMARKED This is a unique opportunity for the water sector to support the green recovery… 1. Jobs and investment are needed across the Midlands 2. The climate needs us to accelerate change 4.1 100 West Mids Mayor’s target date for zero CO2 emission are 4.0 CO emissions 80 2 falling steadily, but 3.9 0.28 not fast enough 0.39 3.8 0.42 4.03 60 Zero CO2 3.7 emissions date 40 3.6 3.76 with current trends Employment (millions) Employment 3.64 3.61 3.5 20 2018 Q2 2020 Q3 2020 Q4 2020 On current trends C02 emissions ,000) C02 emissions (gigatons Employment Jobs lost post covid 0 the Midlands will not reach its target 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2041 2433 Predictions are for the Midlands to lose over 400,000 jobs by Q4 this year 2006 3. -

Wilmington Funds Holdings Template DRAFT

Wilmington Global Alpha Equities Fund as of 5/31/2021 (Portfolio composition is subject to change) ISSUER NAME % OF ASSETS USD/CAD FWD 20210616 00050 3.16% DREYFUS GOVT CASH MGMT-I 2.91% MORGAN STANLEY FUTURE USD SECURED - TOTAL EQUITY 2.81% USD/EUR FWD 20210616 00050 1.69% MICROSOFT CORP 1.62% USD/GBP FWD 20210616 49 1.40% USD/JPY FWD 20210616 00050 1.34% APPLE INC 1.25% AMAZON.COM INC 1.20% ALPHABET INC 1.03% CANADIAN NATIONAL RAILWAY CO 0.99% AIA GROUP LTD 0.98% NOVARTIS AG 0.98% TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 0.91% INTACT FINANCIAL CORP 0.91% CHARLES SCHWAB CORP/THE 0.91% FACEBOOK INC 0.84% FORTIVE CORP 0.81% BRENNTAG SE 0.77% COPART INC 0.75% CONSTELLATION SOFTWARE INC/CANADA 0.70% UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC 0.70% AXA SA 0.63% FIDELITY NATIONAL INFORMATION SERVICES INC 0.63% BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC 0.62% PFIZER INC 0.62% TOTAL SE 0.61% MEDICAL PROPERTIES TRUST INC 0.61% VINCI SA 0.60% COMPASS GROUP PLC 0.60% KDDI CORP 0.60% BAE SYSTEMS PLC 0.57% MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS INC 0.57% NATIONAL GRID PLC 0.56% PUBLIC STORAGE 0.56% NVR INC 0.53% AMERICAN TOWER CORP 0.53% MEDTRONIC PLC 0.51% PROGRESSIVE CORP/THE 0.50% DANAHER CORP 0.50% MARKEL CORP 0.49% JOHNSON & JOHNSON 0.48% BUREAU VERITAS SA 0.48% NESTLE SA 0.47% MARSH & MCLENNAN COS INC 0.46% ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING LTD 0.45% LOCKHEED MARTIN CORP 0.45% ALPHABET INC 0.44% MERCK & CO INC 0.43% CINTAS CORP 0.42% EXPEDITORS INTERNATIONAL OF WASHINGTON INC 0.41% MCDONALD'S CORP 0.41% RIO TINTO PLC 0.41% IDEX CORP 0.40% DIAGEO PLC 0.40% LENNOX INTERNATIONAL INC 0.40% PNC FINANCIAL SERVICES GROUP INC/THE 0.40% ACCENTURE -

Sellafield What to Do in a Radiation Emergency Booklet

WHAT TO DO IN AN Emergency At Sellafield This information is prepared for everyone within the Detailed Emergency Planning Zone and the Inner Emergency Planning Zone for the Sellafield Site. EMERGENCY INFORMATION Listen to local radio. Monitor social media platforms. Dial the Sellafield Emergency Information Line on 29th September 2021 It is important that you study this booklet carefully and keep it in a safe and prominent place. WHAT TO DO IN AN EMERGENCY Introduction • This booklet gives advice on what to do in the event of an emergency at the Sellafield Site. • Sellafield is Europe’s largest single nuclear site and stores and handles industrial size quantities of radioactive material. Although unlikely, an emergency could occur involving material being stored and processed on the Site. In addition, Sellafield also holds a large inventory of other hazardous substances and again although unlikely an emergency could occur involving the chemicals being utilised on the Site. • It must be stressed that the possibility of such emergencies occurring is remote and that the design and operation of all plants on the site are independently monitored by the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR), Health and Safety Executive (HSE) and Environment Agency (EA). • Current assessments of the radiological hazards indicate that areas between 6.1km & 8km from the centre of the Sellafield Site could be the most likely areas to be directly affected during and following a radiation emergency, this area is referred to as the Detailed Emergency Planning Zone (DEPZ). To see its geographical extent please see map A (pg13) & C (pg20). • In addition, other assessments of the chemical hazards indicate that an area up to 2km from the centre of the Sellafield Site could be the most likely area to be directly affected during and following a chemical emergency, this area is referred to as the Inner Emergency Planning Zone (IEPZ). -

CLITHEROE ROAD, WHALLEY Utilities Study Commercial Estates Group 31/01/2013 Revised: 08/02/2013

CLITHEROE ROAD, WHALLEY Utilities Study Commercial Estates Group 31/01/2013 Revised: 08/02/2013 Quality Management Issue/revision Issue 1 Revision 1 Revision 2 Revision 3 Remarks DRAFT DRAFT Date 31/01/2013 08/02/2013 Prepared by C Scott C Scott Signature Checked by C Cozens C Cozens Signature Authorised by C Cozens C Cozens Signature Project number 50600485 50600485 File reference S:\50600485 - Clitheroe Road, S:\50600485 - Clitheroe Whalley\C Road, Whalley\C Documents\Reports\Working\ Documents\Reports\Working 2013 Utilities Study \2013 Utilities Study S:\50600485 - Clitheroe Road, Whalley\C Documents\Reports\Working\2013 Utilities Study Project number: 50600485 Dated: 31/01/2013 2 Revised: 08/02/2013 CLITHEROE ROAD, WHALLEY Utilities Study 31/01/2013 Client Commercial Estates Group Consultant WSP UK Limited Three White Rose Office Park Leeds LS11 0DL UK Tel: +44 (0)11 3395 6200 Fax: +44 (0)11 3395 6201 www.wspgroup.co.uk Registered Address WSP UK Limited 01383511 WSP House, 70 Chancery Lane, London, WC2A 1AF 3 Table of Contents Executive Summary........................................................................... 5 1 Introduction ............................................................................... 6 2 Existing Site .............................................................................. 7 3 Water Supply ............................................................................ 8 4 Gas Supply ............................................................................. 13 5 Electricity Supply .................................................................... -

Annex 1: Parker Review Survey Results As at 2 November 2020

Annex 1: Parker Review survey results as at 2 November 2020 The data included in this table is a representation of the survey results as at 2 November 2020, which were self-declared by the FTSE 100 companies. As at March 2021, a further seven FTSE 100 companies have appointed directors from a minority ethnic group, effective in the early months of this year. These companies have been identified through an * in the table below. 3 3 4 4 2 2 Company Company 1 1 (source: BoardEx) Met Not Met Did Not Submit Data Respond Not Did Met Not Met Did Not Submit Data Respond Not Did 1 Admiral Group PLC a 27 Hargreaves Lansdown PLC a 2 Anglo American PLC a 28 Hikma Pharmaceuticals PLC a 3 Antofagasta PLC a 29 HSBC Holdings PLC a InterContinental Hotels 30 a 4 AstraZeneca PLC a Group PLC 5 Avast PLC a 31 Intermediate Capital Group PLC a 6 Aveva PLC a 32 Intertek Group PLC a 7 B&M European Value Retail S.A. a 33 J Sainsbury PLC a 8 Barclays PLC a 34 Johnson Matthey PLC a 9 Barratt Developments PLC a 35 Kingfisher PLC a 10 Berkeley Group Holdings PLC a 36 Legal & General Group PLC a 11 BHP Group PLC a 37 Lloyds Banking Group PLC a 12 BP PLC a 38 Melrose Industries PLC a 13 British American Tobacco PLC a 39 Mondi PLC a 14 British Land Company PLC a 40 National Grid PLC a 15 BT Group PLC a 41 NatWest Group PLC a 16 Bunzl PLC a 42 Ocado Group PLC a 17 Burberry Group PLC a 43 Pearson PLC a 18 Coca-Cola HBC AG a 44 Pennon Group PLC a 19 Compass Group PLC a 45 Phoenix Group Holdings PLC a 20 Diageo PLC a 46 Polymetal International PLC a 21 Experian PLC a 47 -

Rio Tinto BHP, Tesco, Sainsbury, Arcelormittal, National Grid

Quarterly Engagement Rio Tinto Report July-September BHP, Tesco, 2020 Sainsbury, ArcelorMittal, National Grid 2 LAPFF QUARTERLY ENGAGEMENT REPORT | JULY-SEPTEMBER 2020 lapfforum.org CLIMATE EMERGENCY Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura Aboriginal Corporation Rio Tinto under pressure from investors over Juukan Gorge As LAPFF has been learning more about “My interaction with Mr. Rio Tinto’s involvement in the destruc- Thompson, in his roles as Chair tion of the historically significant caves of both Rio Tinto and 3i, has been at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia, there have been increasing concerns positive thus far. However, I sense about the company’s corporate govern- that investors are losing confidence ance practices. Consequently, the Forum in his leadership and in his board at – along with other investor groups, most Rio Tinto. It will be a long road back What happened at prominently the Australasian Centre for for the company.” Juukan Gorge? Corporate Responsibility (ACCR) - has been pushing the company to review its Cllr Doug McMurdo In May, Rio Tinto destroyed 46,000-year- corporate governance arrangements. old Aboriginal caves in the Juukan One of the main strategies in this Gorge region of Western Australia. The engagement has been to issue press responding to information issued by explosions were part of a government releases citing LAPFF’s concerns as vari- Australian Parliamentary inquiries into sanctioned mining exploration in ous details of Rio Tinto’s practices were this matter. There appears to be increas- the region. The caves are of cultural revealed through a range of investiga- ing evidence of corporate governance fail- significance to the Puutu Kunti tions. -

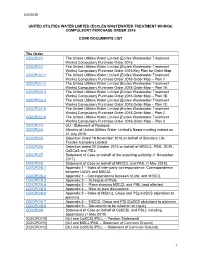

Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 Core Documents List

6/6/2018 UNITED UTILITIES WATER LIMITED (ECCLES WASTEWATER TREATMENT WORKS) COMPULSORY PURCHASE ORDER 2016 CORE DOCUMENTS LIST The Order CD/CPO/1 The United Utilities Water Limited (Eccles Wastewater Treatment Works) Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 CD/CPO/2 The United Utilities Water Limited (Eccles Wastewater Treatment Works) Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 Key Plan for Order Map CD/CPO/2.1 The United Utilities Water Limited (Eccles Wastewater Treatment Works) Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 Order Map – Plan 1 CD/CPO/2.2 The United Utilities Water Limited (Eccles Wastewater Treatment Works) Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 Order Map – Plan 1A CD/CPO/2.3 The United Utilities Water Limited (Eccles Wastewater Treatment Works) Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 Order Map – Plan 1B CD/CPO/2.4 The United Utilities Water Limited (Eccles Wastewater Treatment Works) Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 Order Map – Plan 1C CD/CPO/2.5 The United Utilities Water Limited (Eccles Wastewater Treatment Works) Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 Order Map – Plan 2 CD/CPO/2.6 The United Utilities Water Limited (Eccles Wastewater Treatment Works) Compulsory Purchase Order 2016 Order Map – Plan 3 CD/CPO/3 UU - Statement of Reasons CD/CPO/4 Minutes of United Utilities Water Limited's Board meeting extract on 21 July 2016 CD/CPO/5 Objection dated 18 November 2016 on behalf of Standard Life Trustee Company Limited CD/CPO/6 Objection dated 20 October 2016 on behalf of MSCCL, PINL, SCPL, CoSCoS and PSLL CD/CPO/7 Statement of Case on behalf of the acquiring authority (1 November -

Constituents & Weights

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE 100 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Group 0.59 UNITED GlaxoSmithKline 3.7 UNITED RELX 1.88 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Admiral Group 0.35 UNITED Glencore 1.97 UNITED Rentokil Initial 0.49 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Anglo American 1.86 UNITED Halma 0.54 UNITED Rightmove 0.29 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Antofagasta 0.26 UNITED Hargreaves Lansdown 0.32 UNITED Rio Tinto 3.41 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ashtead Group 1.26 UNITED Hikma Pharmaceuticals 0.22 UNITED Rolls-Royce Holdings 0.39 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Associated British Foods 0.41 UNITED HSBC Hldgs 4.5 UNITED Royal Dutch Shell A 3.13 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AstraZeneca 6.02 UNITED Imperial Brands 0.77 UNITED Royal Dutch Shell B 2.74 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Auto Trader Group 0.32 UNITED Informa 0.4 UNITED Royal Mail 0.28 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Avast 0.14 UNITED InterContinental Hotels Group 0.46 UNITED Sage Group 0.39 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aveva Group 0.23 UNITED Intermediate Capital Group 0.31 UNITED Sainsbury (J) 0.24 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aviva 0.84 UNITED International Consolidated Airlines 0.34 UNITED Schroders 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM Group KINGDOM KINGDOM B&M European Value Retail 0.27 UNITED Intertek Group 0.47 UNITED Scottish Mortgage Inv Tst 1 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM BAE Systems 0.89 UNITED ITV 0.25 UNITED Segro 0.69 UNITED KINGDOM -

International Value Fund Q3 Portfolio Holdings

Putnam International Value Fund The fund's portfolio 3/31/21 (Unaudited) COMMON STOCKS (96.1%)(a) Shares Value Aerospace and defense (0.7%) BAE Systems PLC (United Kingdom) 137,249 $955,517 955,517 Airlines (1.2%) Qantas Airways, Ltd. (voting rights) (Australia)(NON) 437,675 1,698,172 1,698,172 Auto components (1.5%) Magna International, Inc. (Canada) 23,813 2,097,257 2,097,257 Automobiles (1.2%) Yamaha Motor Co., Ltd. (Japan) 70,500 1,742,181 1,742,181 Banks (14.7%) AIB Group PLC (Ireland)(NON) 708,124 1,861,795 Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, Ltd. (Australia) 165,820 3,561,114 BNP Paribas SA (France)(NON) 28,336 1,723,953 CaixaBank SA (Spain) 295,756 915,292 DBS Group Holdings, Ltd. (Singapore) 60,800 1,311,573 DNB ASA (Norway) 71,016 1,511,129 Hana Financial Group, Inc. (South Korea) 38,370 1,447,668 ING Groep NV (Netherlands) 362,345 4,432,786 Lloyds Banking Group PLC (United Kingdom)(NON) 1,014,265 594,752 Mizuho Financial Group, Inc. (Japan) 73,920 1,066,055 Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB (Sweden)(NON) 30,210 368,223 Sumitomo Mitsui Financial Group, Inc. (Japan) 67,400 2,450,864 21,245,204 Beverages (1.0%) Asahi Group Holdings, Ltd. (Japan) 33,700 1,426,966 1,426,966 Building products (1.1%) Compagnie De Saint-Gobain (France)(NON) 27,404 1,617,117 1,617,117 Capital markets (3.6%) Partners Group Holding AG (Switzerland) 1,115 1,423,906 Quilter PLC (United Kingdom) 798,526 1,759,704 UBS Group AG (Switzerland)(NON) 132,852 2,057,122 5,240,732 Chemicals (1.1%) LANXESS AG (Germany) 21,951 1,618,138 1,618,138 Construction and engineering (2.5%) Vinci SA (France) 35,382 3,624,782 3,624,782 Construction materials (1.2%) CRH PLC (Ireland) 38,290 1,794,760 1,794,760 Containers and packaging (0.8%) SIG Combibloc Group AG (Switzerland) 51,554 1,192,372 1,192,372 Diversified financial services (2.1%) Eurazeo SA (France)(NON) 20,542 1,563,415 ORIX Corp.