Rogue Memories: Reflections on Trauma, Art, and Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

BREAD and BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021

BREAD AND BAKERY DASHBOARD Northwest Syria Bread and Bakery Assistance 12 MARCH 2021 ISSUE #7 • PAGE 1 Reporting Period: DECEMBER 2020 Lower Shyookh Turkey Turkey Ain Al Arab Raju 92% 100% Jarablus Syrian Arab Sharan Republic Bulbul 100% Jarablus Lebanon Iraq 100% 100% Ghandorah Suran Jordan A'zaz 100% 53% 100% 55% Aghtrin Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali 52% 100% Afrin A'zaz Mare' 100% of the Population Sheikh Menbij El-Hadid 37% 52% in NWS (including Tell 85% Tall Refaat A'rima Abiad district) don’t meet the Afrin 76% minimum daily need of bread Jandairis Abu Qalqal based on the 5Ws data. Nabul Al Bab Al Bab Ain al Arab Turkey Daret Azza Haritan Tadaf Tell Abiad 59% Harim 71% 100% Aleppo Rasm Haram 73% Qourqeena Dana AleppoEl-Imam Suluk Jebel Saman Kafr 50% Eastern Tell Abiad 100% Takharim Atareb 73% Kwaires Ain Al Ar-Raqqa Salqin 52% Dayr Hafir Menbij Maaret Arab Harim Tamsrin Sarin 100% Ar-Raqqa 71% 56% 25% Ein Issa Jebel Saman As-Safira Maskana 45% Armanaz Teftnaz Ar-Raqqa Zarbah Hadher Ar-Raqqa 73% Al-Khafsa Banan 0 7.5 15 30 Km Darkosh Bennsh Janudiyeh 57% 36% Idleb 100% % Bread Production vs Population # of Total Bread / Flour Sarmin As-Safira Minimum Needs of Bread Q4 2020* Beneficiaries Assisted Idleb including WFP Programmes 76% Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Hajeb in December 2020 0 - 99 % Mhambal Saraqab 1 - 50,000 77% 61% Tall Ed-daman 50,001 - 100,000 Badama 72% Equal or More than 100% 100,001 - 200,000 Jisr-Ash-Shugur Idleb Ariha Abul Thohur Monthly Bread Production in MT More than 200,000 81% Khanaser Q4 2020 Ehsem Not reported to 4W’s 1 cm 3720 MT Subsidized Bread Al Ma'ra Data Source: FSL Cluster & iMMAP *The represented percentages in circles on the map refer to the availability of bread by calculating Unsubsidized Bread** Disclaimer: The Boundaries and names shown Ma'arrat 0.50 cm 1860 MT the gap between currently produced bread and bread needs of the population at sub-district level. -

Download the Publication

Viewpoints No. 99 Mission Impossible? Triangulating U.S.- Turkish Relations with Syria’s Kurds Amberin Zaman Public Policy Fellow, Woodrow Wilson Center; Columnist, Diken.com.tr and Al-Monitor Pulse of the Middle East April 2016 The United States is trying to address Turkish concerns over its alliance with a Syrian Kurdish militia against the Islamic State. Striking a balance between a key NATO ally and a non-state actor is growing more and more difficult. Middle East Program ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ On April 7 Syrian opposition rebels backed by airpower from the U.S.-led Coalition against the Islamic State (ISIS) declared that they had wrested Al Rai, a strategic hub on the Turkish border from the jihadists. They hailed their victory as the harbinger of a new era of rebel cooperation with the United States against ISIS in the 98-kilometer strip of territory bordering Turkey that remains under the jihadists’ control. Their euphoria proved short-lived: On April 11 it emerged that ISIS had regained control of Al Rai and the rest of the areas the rebels had conquered in the past week. Details of what happened remain sketchy because poor weather conditions marred visibility. But it was still enough for Coalition officials to describe the reversal as a “total collapse.” The Al Rai fiasco is more than just a battleground defeat against the jihadists. It’s a further example of how Turkey’s conflicting goals with Washington are hampering the campaign against ISIS. For more than 18 months the Coalition has been striving to uproot ISIS from the 98- kilometer chunk of the Syrian-Turkish border that is generically referred to the “Manbij Pocket” or the Marea-Jarabulus line. -

International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Violations in Syria

Helpdesk Report International humanitarian law and human rights violations in Syria Iffat Idris GSDRC, University of Birmingham 5 June 2017 Question Provide a brief overview of the current situation with regard to international humanitarian law and human rights violations in Syria. Contents 1. Overview 2. Syrian government and Russia 3. Armed Syrian opposition (including extremist) groups 4. Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) 5. Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) 6. International coalition 7. References The K4D helpdesk service provides brief summaries of current research, evidence, and lessons learned. Helpdesk reports are not rigorous or systematic reviews; they are intended to provide an introduction to the most important evidence related to a research question. They draw on a rapid desk-based review of published literature and consultation with subject specialists. Helpdesk reports are commissioned by the UK Department for International Development and other Government departments, but the views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of DFID, the UK Government, K4D or any other contributing organisation. For further information, please contact [email protected]. 1. Overview All parties involved in the Syrian conflict have carried out extensive violations of international humanitarian law and human rights. In particular, all parties are guilty of targeting civilians. Rape and sexual violence have been widely used as a weapon of war, notably by the government, ISIL1 and extremist groups. The Syrian government and its Russian allies have used indiscriminate weapons, notably barrel bombs and cluster munitions, against civilians, and have deliberately targeted medical facilities and schools, as well as humanitarian personnel and humanitarian objects. -

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 31 May - 6 June 2021

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 31 May - 6 June 2021 SYRIA SUMMARY • The predominantly Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) cracks down on anti-conscription protests in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate. • The Government of Syria (GoS) offers to defer military service for people wanted in southern Syria. • ISIS assassinates a prominent religious leader in Deir-ez-Zor city. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 6 June 2021. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see footnote 1. Page 1 of 5 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 31 May - 6 June 2021 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 Figure 2: Anti-conscription protests and related events in Manbij, Aleppo Governorate between 31 May – 6 June. Data from The Carter Center and ACLED. Conscription in Northwest Syria In 2019, the Kurdish Autonomous Administration (KAA) issued a controversial conscription law for territories under its control.2 in February, the Syrian Network For Human Rights claimed that the conscription of teachers deprived half a million students of a proper education. 3 People in the region argue that the forcible recruitment and arrests by SDF have disrupted economic life.4 In late May, the SDF escalated its recruitment effort.5 31 May 1 Figure 1 depicts areas of the dominant actors’ control and influence. While “control” is a relative term in a complex, dynamic conflict, territorial control is defined as an entity having power over use of force as well as civil/administrative functions in an area. Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah maintain a presence in Syrian government-controlled territory. Non-state organized armed groups (NSOAG), including the Kurdish-dominated SDF and Turkish-backed opposition groups operate in areas not under GoS control. -

Timeline of International Response to the Situation in Syria

Timeline of International Response to the Situation in Syria Beginning with dates of a few key events that initiated the unrest in March 2011, this timeline provides a chronological list of important news and actions from local, national, and international actors in response to the situation in Syria. Skip to: [2012] [2013] [2014] [2015] [2016] [Most Recent] Acronyms: EU – European Union PACE – Parliamentary Assembly of the Council CoI – UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria of Europe FSA – Free Syrian Army SARC – Syrian Arab Red Crescent GCC – Gulf Cooperation Council SASG – Special Adviser to the Secretary- HRC – UN Human Rights Council General HRW – Human Rights Watch SES – UN Special Envoy for Syria ICC – International Criminal Court SOC – National Coalition of Syrian Revolution ICRC – International Committee of the Red and Opposition Forces Cross SOHR – Syrian Observatory for Human Rights IDPs – Internally Displaced People SNC – Syrian National Council IHL – International Humanitarian Law UN – United Nations ISIL – Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant UNESCO – UN Educational, Scientific and ISSG – International Syria Support Group Cultural Organization JSE – UN-Arab League Joint Special Envoy to UNGA – UN General Assembly Syria UNHCR – UN High Commissioner for LAS – League of Arab States Refugees NATO – North Atlantic Treaty Organization UNICEF – UN Children’s Fund OCHA – UN Office for the Coordination of UNRWA – UN Relief Works Agency for Humanitarian Affairs Palestinian Refugees OIC – Organization of Islamic Cooperation UNSC – UN Security Council OHCHR – UN Office of the High UNSG – UN Secretary-General Commissioner for Human Rights UNSMIS – UN Supervision Mission in Syria OPCW – Organization for the Prohibition of US – United States Chemical Weapons 2011 2011: Mar 16 – Syrian security forces arrest roughly 30 of 150 people gathered in Damascus’ Marjeh Square for the “Day of Dignity” protest, demanding the release of imprisoned relatives held as political prisoners. -

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo

Turkey | Syria: Flash Update No. 2 Developments in Northern Aleppo, Azaz (as of 1 June 2016) Summary An estimated 16,150 individuals in total have been displaced by fighting since 27 May in the northern Aleppo countryside, with most joining settlements adjacent to the Bab Al Salam border crossing point, Azaz town, Afrin and Yazibag. Kurdish authorities in Afrin Canton have allowed civilians unimpeded access into the canton from roads adjacent to Azaz and Mare’ since 29 May in response to ongoing displacement near hostilities between ISIL and NSAGs. Some 9,000 individuals have been afforded safe passage to leave Mare’ and Sheikh Issa towns after they were trapped by fighting on 27 May; however, an estimated 5,000 civilians remain inside despite close proximity to frontlines. Humanitarian organisations continue to limit staff movement in the Azaz area for safety reasons, and some remain in hibernation. Limited, cautious humanitarian service delivery has started by some in areas of high IDP concentration. The map below illustrates recent conflict lines and the direction of movement of IDPs: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Coordination Saves Lives | www.unocha.org Turkey | Syria: Azaz, Flash Update No.2 Access Overview Despite a recent decline in hostilities since May 27, intermittent clashes continue between NSAGs and ISIL militants on the outskirts of Kafr Kalbien, Kafr Shush, Baraghideh, and Mare’ towns. A number of counter offensives have been coordinated by NSAGs operating in the Azaz sub district, hindering further advancements by ISIL militants towards Azaz town. As of 30 May, following the recent decline in escalations between warring parties, access has increased for civilians wanting to leave Azaz and Mare’ into areas throughout Afrin canton. -

Weekly Conflict Summary March 9-15, 2017

Weekly Conflict Summary March 9-15, 2017 This reporting period saw consistently high levels of violence throughout Syria. Conflict in the Eastern Ghouta region outside Damascus remained particularly high, especially in Qaboun, where pro-government forces are attempting to advance. Pro-government forces destroyed several opposition tunnels at the start of the week as they work to consolidate control over gains made in the previous reporting period. Figure 1: Heatmap showing relative levels of recorded conflict throughout the country. On March 10, a Shi’a pilgrimage site in the Old City of Damascus was struck by large blasts, killing many worshippers. On the same day, two suicide bombings hit areas of the Kafr Sousa district of Damascus, killing primarily soldiers. The Kafr Sousa bombings were claimed by Haiy’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). On March 11, the US declared HTS a terrorist organization (like earlier iterations of the group, Jabhat Fatah al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra). On March 15, two suicide bombings hit areas of Damascus, the first at the Palace of Justice near Nasr Street, and the second at a restaurant on the main road that runs through al-Rabweh. These two blasts killed over 50 civilians and have not been claimed by any group. In southern Syria, Daraa city saw heavy conflict, especially on the western portion of the city frontline as the al-Mawt Wala al-Muzaleh (Death Rather than Humiliation) opposition offensive continued around the al-Menshiyyeh neighborhood. Opposition-held southern Daraa endured significant conflict as well, due to shelling and airstrikes by the Syrian government. -

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 27 April - 3 May 2020

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 27 April - 3 May 2020 SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST| Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) faced protests after opening a controversial commercial crossing with Government of Syria (GoS). A fuel tanker explosion in Afrin killed 53 people. Infighting between Turkish- backed armed opposition groups escalated in Jarabulus, Aleppo Governorate. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | Clashes between As-Sweida and Dara’a militias continued. Attacks against GoS personnel and positions continued in Dara’a Governorate. Israel attacked pro-Iranian militias and GoS positions across southern Syria. ISIS killed several GoS armed forces personnel. • NORTHEAST | ISIS prisoners attempted to escape Ghoweran jail in Al- Hassakah Governorate. Violence against civilians continued across northeast Syria. Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) faced increased attacks from unidentified gunmen and Turkish armed forces. Coalition forces carried out their first airstrikes since 11 March. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 3 May 2020. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 6 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 27 April – 3 May 2020 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 After announcing plans to open a commercial crossing with GoS territory, protests erupted against HTS (see figure 2). Civilians protested the crossing over fears of normalization with GoS and of spreading COVID-19. On 30 April, Maaret al Naasan (Idlib Governorate) residents protested at the crossing and blocked commercial trucks attempting to cross into GoS areas. HTS violently dispersed the protests, killing one. Following the protests, HTS brought reinforcements to Maaret al Naasan. The same day, HTS announced that it had suspended the opening of the commercial crossing.2 On 1 May, protests continued against HTS across Idlib and Aleppo Governorates in 10 locations.3 Smaller protests were recorded in 2 May in Kafr Takharim and Ariha in Idlib Governorate. -

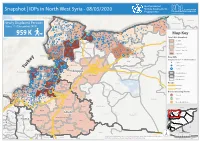

Snapshot | Idps in North West Syria - 08/03/2020 Needs Assessment CCCM CLUSTER SUPPORTING DISPLACED COMMUNITIES Programme

Humanitarian Snapshot | IDPs in North West Syria - 08/03/2020 Needs Assessment CCCM CLUSTER SUPPORTING DISPLACED COMMUNITIES Programme www.globalcccmcluster.org Meydan-I-Ekbez Jarablus Ain al Arab Newly Displaced Persons Lower Shyookh st Bulbul (Since 1 of December 2019) Ghandorah Jarablus Raju Bab Al Salam 959 K Sharan Al-Ra'ee Map Key Suran Ar-Ra'ee Ma'btali A'zaz Total IDPs (Baseline) Menbij No IDPs Aghtrin < 25,000 Sheikh El-Hadid 25,000 - 60,000 Sarin Afrin Tall Refaat Mare' A'rima Abu Qalqal 60,000 - 120,000 Jandairis Al Bab >120,000 Olive Branch Nabul New IDPs Atmeh (Displaced since 1st of December) Tadaf Haritan <1,000 Dana Daret Azza 1,000 - 5,000 Bab Al Hawa Rasm Haram El-Imam Turkey Qourqeena >5,000 Harim Friendship Bridge Aleppo Salqin Eastern Kwaires Country Border Atareb Jebel Saman Governorate Kafr Takharim Dayr Har Jurneyyeh Sub districts Maaret Tamsrin As-Sara Roads Teftnaz Highway Darkosh Armanaz Darkosh Zarbah Hadher Maskana Bennsh Primary Banan Kherbet Eljoz Idleb Sarmin Border Crossing Points Janudiyeh Samira Closed M4 Hajeb Open Jisr-Ash-Shugur Saraqab Al-Khafsa Yunesiya Sporadically Open Ariha Badama Mhambal M5 Rabee'a Abul Thohur Tall Ed-daman Kansaba Turkey Ehsem MansuraAl-Hasakeh Ziyara Idleb Aleppo Idleb Salanfa Khanaser Ar-Raqqa Ma'arrat An Nu'man Hama Deir-ez-Zor Hama Sanjar Kafr Nobol Homs Shat-ha Heish Lattakia Rural Damascus Iraq Jobet Berghal Dar'a Madiq Castle Tamanaah Jordan Al-Qardaha Khan Shaykun Hamra ± 0 5 10 20 As-Suqaylabiyah CCCM Cluster Turkey hub; Source: CCCM Cluster databaseAs-Saan, Turkey -

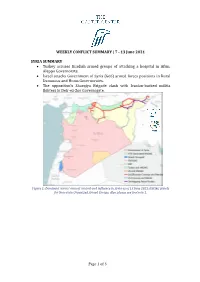

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 7 - 13 June 2021

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 7 - 13 June 2021 SYRIA SUMMARY • Turkey accuses Kurdish armed groups of attacking a hospital in Afrin, Aleppo Governorate. • Israel attacks Government of Syria (GoS) armed forces positions in Rural Damascus and Homs Governorates. • The opposition’s Sharqiya Brigade clash with Iranian-backed militia fighters in Deir-ez-Zor Governorate. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 13 June 2021. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see footnote 1. Page 1 of 5 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 7 – 13 June 2021 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 Figure 2: Conflict between Turkish armed forces and Turkish-backed armed opposition groups on the one side and GoS armed forces and Kurdish militias on the other between 7-13 June 2021. Data from The Carter Center and ACLED. Conflict in Aleppo Governorate Turkey justifies its control of territory in northern Syria as a secure zone along the border to prevent alleged threats from armed Kurdish groups. 2 Shelling and clashes along the frontlines between Turkish armed forces and Turkish-backed armed opposition groups on the one side and Government of Syria (GoS) armed forces and the predominantly Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) on the other side are frequent. 12 June Unidentified missile strikes destroyed the Al-Shifa hospital in Afrin, Aleppo Governorate, killing 15 people. 34 Turkish armed forces accused the SDF of 1 Figure 1 depicts areas of the dominant actors’ control and influence. While “control” is a relative term in a complex, dynamic conflict, territorial control is defined as an entity having power over use of force as well as civil/administrative functions in an area. -

Nw Syria Sitrep23 20201221.Pdf (English)

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC Recent Developments in Northwest Syria Situation Report No. 23 - As of 21 December 2020 2.7M displaced people living in northwest Syria 1,214 active IDP sites in northwest Syria 1.5M displaced people living in IDP sites 80% of people in IDP sites are women and children Source: CCCM Cluster, November 2020 The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. HIGHLIGHTS • 19,447 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed in northwest Syria, while COVID-19 associated deaths tripled since last month. • Two new COVID-19 testing laboratories, one additional hospital, four new COVID-19 community-based treatment centres (CCTC) and a quarantine centre were operationalised in northwest Syria during the reporting period. • A funding shortfall leading to significant gaps in water and sanitation services has resulted in people in need of these services increasing by over 1.8 million people in the last 3 months, including for water provision through networks and water stations, hygiene kits, solid waste disposal, sanitation services and water trucking services. • Nearly 250,000 people were reached by Shelter/NFI partners with winterisation assistance in November. Such support remains vital as winter progresses, including in the form of multi-purpose cash. SITUATION OVERVIEW Ongoing hostilities: Hostilities continue to impact communities across northwest Syria, especially in areas near the M4 and M5 highways in Idleb governorate. With some 400,000 people living along the M4 and M5 highways, any escalation would have devastating humanitarian consequences. The security situation is further undermined by the prevalence of explosive hazards and in-fighting between non-state armed groups (NSAGs), which take a toll on civilian life.