Queen V William Robert Thompson Morrow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1951 Census Down County Report

GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF POPULATION OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1951 County of Down Printed & presented pursuant to 14 & 15 Geo. 6, Ch, 6 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1954 PRICE 7* 6d NET GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF POPULATION OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1951 County of Down Printed & presented pursuant to 14 & 15 Geo. 6, Ch. 6 BELFAST : HER MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE 1954 PREFACE Three censuses of population have been taken since the Government of Northern Irel&nd was established. The first enumeration took place in 1926 and incorporated questions relating to occupation and industry, orphanhood and infirmities. The second enumeration made in 1937 was of more limited scope and was intended to bridge the gap between the census of 1926 and the census which it was proposed to take in 1941, but which had to be abandoned owing to the outbreak of war. The census taken as at mid-night of 8th-9th April, 1951, forms the basis of this report and like that in 1926 questions were asked as to the occupations and industries of the population. The length of time required to process the data collected at an enumeration before it can be presented in the ultimate reports is necessarily considerable. In order to meet immediate requirements, however, two Preliminary Reports on the 1951 census were published. The first of these gave the population figures by administrative areas and towns and villages, and by Counties and County Boroughs according to religious pro fession. The Second Report, which was restricted to Counties and County Boroughs, gave the population by age groups. -

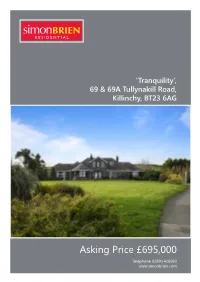

Asking Price £695,000

‘Tranquility’, 69 & 69A Tullynakill Road, Killinchy, BT23 6AG Asking Price £695,000 Telephone 02890 428989 www.simonbrien.com KEY FEATURES SUMMARY • Stunning detached residence with panoramic views across surrounding landscape and Strangford Lough Occupying an elevated position with stunning panoramic • Site measuring circa 5 acres in total with two paddocks views across Strangford Lough and surrounding • Bright and spacious accommodation throughout all with countryside, this superb detached residence offers spacious, superb views adaptable accommodation throughout. • Impressive dining entrance hall with log burning stove • Drawing room with open fire and ornate marble Set within a private site measuring circa 5 acres including surround two paddocks to the front measuring circa 3.5 acres, this • Open plan kitchen dining area with casual dining space, elegant property is sure to appeal to those seeking to opening onto front terrace take full advantage of a countryside setting, yet in close • Fitted kitchen with range of integrated appliances proximity to many amenities including restaurants, shops • Five bedrooms over two floors, including two with and recreational facilities including golf and sailing clubs, ensuite facilities and master with additional dressing Daft Eddy’s and Balloo House. room • Two additional bathroom suites on ground floor Internally this fine home offers a spacious dining hall, • Large boot room and separate utility room impressive drawing room with open fire and open plan • Oil Fired central heating / Upvc double glazed windows fitted kitchen with casual dining, all maintaining superb • Driveway car parking to front leading to rear gravel views across the surrounding scenery. In addition there are courtyard five bedrooms over the ground and first floor, two with • Two loose boxes ensuite facilities, including master suite with additional • Additional 1 bed cottage to rear (currently rented for dressing room, all with stunning views and two further £650/mth) bathrooms with white suites. -

Ards and North Down Borough Council a G E N

ARDS AND NORTH DOWN BOROUGH COUNCIL 31 October 2018 Dear Sir/Madam You are hereby invited to attend a meeting of the Environment Committee of the Ards and North Down Borough Council which will be held in the Council Chamber, 2 Church Street, Newtownards on Wednesday 7 November 2018 commencing at 7.00pm. Tea, coffee and sandwiches will be available from 6.00pm. Yours faithfully Stephen Reid Chief Executive Ards and North Down Borough Council A G E N D A 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Deputations 3.1. Alan McIlwaine – Compostable Garden Waste 3.2. NI Water – Pollution on Beaches 4. Environment Directorate Budgetary Control Report April 18 – September 2018 (Report attached) 5. Technical Budget 2019/20 - Maintenance Strategy Refurbishment Budget Report 2019/20 (Report attached) 6. Recycling Community Investment Fund – Spending Proposal (Report attached) 7. Call for Action on Single Use Plastics by Large Supermarket Retailers (Report attached) 8. Performance Report Neighbourhood Environment Team (Report attached) 9. Review of Road Closure Legislation (Report attached) 10. Off-Street Car Parking Management (Report attached) 11. Street Naming Report (Report attached) 12. Court Proceedings (Report attached) 13. Grant and Transfer of Entertainment Licences (Report attached) 14. Grant of Pavement Café Licences (Report attached) 15. Amendments to the Memorial Benches Policy (Report attached) 16. Notices of Motion 16.1 Notice of Motion submitted by Councillor Douglas That this Council writes to the Department for Infrastructure requesting the Department give due consideration to purchasing and implementing items known as ‘litter traps’ or similar devices which are placed in gullies and overflow pipes where they collect waste products, which are gathered and designed to be disposed of without entering our rivers etc. -

Historic Environment

Local Development Plan (LDP) - Position Paper Historic Environment 2 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................. 5 Introduction............................................................................................................... 6 Regional Policy Context .......................................................................................... 6 The Regional Development Strategy (RDS) 2035 ...................................................... 6 Planning Policy Statement 6 and the Strategic Planning Policy Statement ................ 7 Role of Local Development Plans ............................................................................... 7 Design and Place-making ........................................................................................... 9 Planning Policy Statement 23: Enabling Development for the Conservation of Significant Places ....................................................................................................... 9 Existing Local Development Plan Context ........................................................... 10 North Down and Ards Area Plan 1984-1995 (NDAAP), Belfast Urban Area Plan, draft Belfast Metropolitan Area Plan 2015 (dBMAP) and Belfast Metropolitan Area Plan 2015 (BMAP) ............................................................................................................ 10 Ards and Down Area Plan 2015 ............................................................................... 11 -

The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers

THE LIST of CHURCH OF IRELAND PARISH REGISTERS A Colour-coded Resource Accounting For What Survives; Where It Is; & With Additional Information of Copies, Transcripts and Online Indexes SEPTEMBER 2021 The List of Parish Registers The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers was originally compiled in-house for the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), now the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), by Miss Margaret Griffith (1911-2001) Deputy Keeper of the PROI during the 1950s. Griffith’s original list (which was titled the Table of Parochial Records and Copies) was based on inventories returned by the parochial officers about the year 1875/6, and thereafter corrected in the light of subsequent events - most particularly the tragic destruction of the PROI in 1922 when over 500 collections were destroyed. A table showing the position before 1922 had been published in July 1891 as an appendix to the 23rd Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records Office of Ireland. In the light of the 1922 fire, the list changed dramatically – the large numbers of collections underlined indicated that they had been destroyed by fire in 1922. The List has been updated regularly since 1984, when PROI agreed that the RCB Library should be the place of deposit for Church of Ireland registers. Under the tenure of Dr Raymond Refaussé, the Church’s first professional archivist, the work of gathering in registers and other local records from local custody was carried out in earnest and today the RCB Library’s parish collections number 1,114. The Library is also responsible for the care of registers that remain in local custody, although until they are transferred it is difficult to ascertain exactly what dates are covered. -

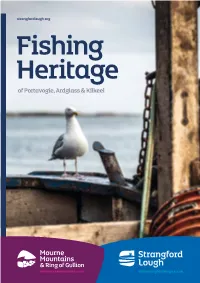

Fishing Heritage of Portavogie Guide (PDF)

strangfordlough.org Fishing Heritage of Portavogie, Ardglass & Kilkeel 3 Copeland Islands A2 Belfast K y l e Lough s to n e R d A2 d W R h d i y n A48 R n e e n y y e o W h H g m i n au y d ll i l U i l l K l p m a p i B e l r l G R r a d n s h a Ho R lyw d Contents A21 Pushing the boat out o o d R d d R y e d b R b n A20 A r u b o A22 d W R 5 The local catch Fishing has been a major industry in County K n i r l A20 b u r b d i R g g h n e i s t n n 6 Improved fishing gear R a Down for many years. Three ports - Kilkeel, n t Steward R d d u M C A55 M d a R C rd r y b e Rd Dun 7 Changing fisheries om ove Portavogie and Ardglass - remain at the C r Rd m centre of the fishing industry today. Their 8 Navigating change Stu p Rd B a ll A2 ydrai Chapel n R communities revolve around the sea. Local 9 Weather & hidden danger d Island A23 d R T rry u 10 People’s stories: past & present a l Lisburn l people and their traditions have strong ties Carrydu u y Q n A2 a k i l 6 l A3 R Rd 13 Fishing moves forward d e to the water. -

The Castlewellan Court Book 1824

THE CASTLEWELLAN COURT BOOK 1824 EDITED BY J. CHRISTOPHER NAPIER Published on the internet 2004 DEDICATED to the memory of Martin McBurney QC RM, whose cruel murder on 16 September 1974 deprived us of a true Justice of the People. I wish to acknowledge with gratitude the huge assistance given by William and Monty Murphy, by the late Desmond McMullan, of Heather Semple, Librarian of the Law Society of Northern Ireland, Terence Bowman, editor of the Mourne Observer, in addition to the countless friends who proffered advice and assistance without which this book could never have been published; in addition to the encouragement of Ann, my wife throughout the long period in which this work was done. J Christopher Napier BA Biographical Note on Editor Master Napier was born in Belfast in 1936, and was educated at St Malachy’s College, Antrim Road, and Queen’s University, Belfast. He practiced as a solicitor in Belfast from 1961 until 1990 when he was appointed Master (Taxing Office) of the Supreme Court of Judicature for Northern Ireland. CONTENTS Frontispiece – Photograph of the Court House as it is today – a public library 1. Introduction and Background a. The Book itself b. The age in which the Book was written c. Castlewellan in 1824 d. The Justices of the Peace and their role e. Notes on the Justices referred to 2. Appendices a. Fines b. Legal Costs c. Produce d. Prices and bargains e. Table of Causes of Action, Crimes and Statutory Offences f. Table of Serious Offences g. Deposition of William McNally h. -

Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork Excavations at Mahee Castle, Co

Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork School of Archaeology and Palaeoecology Queen’s University Belfast Data Structure Report: No. 11. Excavations at Mahee Castle, Co. Down AE/02/79 On behalf of Data Structure Report: Mahee Castle, Mahee Island, County Down Philip Macdonald (CAF DSR 011) (Licence No. AE/02/79) (SMR No. Down 017:004) Contents Chapter 1: Summary 1 Chapter 2: Introduction 6 Chapter 3: Excavation 14 Chapter 4: Discussion 27 Chapter 5: Recommendations for further work 34 Bibliography 36 Appendix 1: Context list 38 Appendix 2: Harris Matrix 39 Appendix 3: Photographic record 40 Appendix 4: Field drawing register 49 Appendix 5: Small finds register 50 Appendix 6: Record of bulk finds 59 Appendix 7: Samples record 60 Appendix 8: Early photographic studies of Mahee Castle 61 Plates 66 Mahee Castle, County Down 2002 (Licence No. AE/02/79) CAF DSR 011 __________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Summary 1.1 Background 1.1.1 Archaeological excavation was undertaken at Mahee Castle (SMR No. Down 017 : 004) on Mahee Island in Strangford Lough, Co. Down in advance of a programme of restoration work undertaken by the Environment and Heritage Service: Built Heritage. Mahee Castle is a ruined tower house located on the northern shore of Mahee Island, close to the causeway to Reagh Island (Grid Reference J52396394). The site is conventionally dated on historical evidence to c.1570. The tower house is built upon an artificial terrace cut into the northeastern end of a drumlin. The back of the terrace is retained by a revetment wall located c.4.0 metres to the southwest of the tower house. -

The Belfast Gazette

NUMBER 3767 The Belfast Gazette Registered as a Newspaper FRIDAY, llth JANUARY, 1980 State Intelligence NORTHERN IRELAND OFFICE Clogher Valley Co-Operative Society Limited (Register No. IP 113) the registered office of which is at 41 Lurgan- The Secretary of State has appointed the following persons glare, Eskra, Omagh, Co. Tyrone, on the -ground that the ' to the Office of High Sheriff in Northern Ireland for the society has ceased to exist-.. year 1980: The society ceases to enjoy the privileges of a registered County Antrim society, .but without prejudice to any liability incurred by Richard Severn Traill, Esq., Ballylough House, Riverside the society, which may be enforced against it as if such Road, Bushmills, Co. Antrim. cancellation had not taken place. County Down Dated 3rd January, 1980. .' .. James Hampden Wolfe Pooler, Esq., Tullynakill. House, /. Martin, Registrar. • 51 Tullynakill Road, Comber, Newtownards. Co. Down. County Londonderry Dr. Ian Robert Oscar Gordon, Old Rectory, Banagher, Notice of Cancellation pursuant to section 15 of the said Denychrier, Dungiven, Co. Londonderry. Act • City of, Belfast Notice is hereby given that the Registrar hasj pursuant to Alderman Michael Godfrey Brown, 35 Holland Park, the Industrial and Provident Societies. Act .(Northern Belfast BT5 6HB. Ireland) 1969, this day cancelled the registration of North County Armagh Ulster Farmers Limited (Register No. IP138) the regis- tered office of which is at Ballyagan, Garvagh, Coleraine, John Reginald Miller, Esq., F.R.C.S., Carrick Brae, Co. Londonderry, on the ground that the society has 146 Gilford Road, Port ado wn, Co. Armagh. ceased to exist. " " County Fermanagh The society ceases to enjoy the privileges of a registered • Matthew. -

Scheduled Historic Monuments Of

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT DIVISION Historic Monuments of Northern Ireland Scheduled Historic Monuments 1st April 2016 NORTHERN IRELAND ENVIRONMENT AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT HISTORIC MONUMENTS OF NORTHERN IRELAND Historic Environment Division identifies, protects, records, investigates and presents Northern Ireland's heritage of archaeological and historic sites and monuments. The Department has statutory responsibility for the sites and monuments in this list which are protected under Article 3 of the Historic Monuments and Archaeological Objects (NI) Order 1995. They are and are listed in alphabetical order of townland name within each county. The Schedule of Historic Monuments at April 2016 This schedule is compiled and maintained by the Department and is available for public consultation at the Monuments and Buildings Record, Waterman House, 5-33 Hill Street, Belfast BT1 2LA. Additions and amendments are made throughout each year and this list supersedes all previously issued lists. To date there are 1,977 scheduled historic monuments. It is an offence to damage or alter a scheduled site in any way. No works should be planned or undertaken at the sites listed here without first consulting with Historic Environment Division and obtaining any necessary Scheduled Monument Consent. The unique reference number for each site is in the last column of each entry and should be quoted in all correspondence. Where sites are State Care and also have a scheduled area they are demarcated with an asterisk in this list The work of scheduling is ongoing, and the fact that a site is not in this list does not diminish its unique archaeological importance. The Northern Ireland Sites and Monuments Record (NISMR) has information on some 16,656 sites of which this scheduled list is about 12% at present. -

County Down Scarce, Rare and Extinct Vascular Plant Register

County Down Scarce, Rare and Extinct Vascular Plant Register Graham Day and Paul Hackney Edited by Julia Nunn Centre for Environmental Data and Recording 2008 Vascular Plant Register County Down County Down Scarce, Rare & Extinct Vascular Plant Register and Checklist of Species Graham Day & Paul Hackney Record editor: Graham Day Authors of species accounts: Graham Day and Paul Hackney General editor: Julia Nunn 2008 These records have been selected from the database held by the Centre for Environmental Data and Recording at the Ulster Museum. The database comprises all known county Down records. The records that form the basis for this work were made by botanists, most of whom were amateur and some of whom were professional, employed by government departments or undertaking environmental impact assessments. This publication is intended to be of assistance to conservation and planning organisations and authorities, district and local councils and interested members of the public. Cover design by Fiona Maitland Cover photographs: Mourne Mountains from Murlough National Nature Reserve © Julia Nunn Hyoscyamus niger © Graham Day Spiranthes romanzoffiana © Graham Day Gentianella campestris © Graham Day MAGNI Publication no. 016 © National Museums & Galleries of Northern Ireland 1 Vascular Plant Register County Down CONTENTS Preface 5 Introduction 7 Conservation legislation categories 7 The species accounts 10 Key to abbreviations used in the text and the records 11 Contact details 12 Acknowledgements 12 Species accounts for scarce, rare and extinct vascular plants 13 Casual species 161 Checklist of taxa from county Down 166 Publications relevant to the flora of county Down 180 Index 182 2 Vascular Plant Register County Down 3 Vascular Plant Register County Down PREFACE County Down is distinguished among Irish counties by its relatively diverse and interesting flora, as a consequence of its range of habitats and long coastline. -

Driving Tours

pp Store and Google Play Google and Store pp A iTunes the from pp A iscover D free the ownload D www.visitstrangfordlough.co.uk TOUR TOUR TOUR www.northdowntourism.com brought to Ulster by Hamilton and 18 KEARNEY VILLAGE 28 SCRABO & THE MEN OF Montgomery, including Rev Blair from BT22 1QQ Kearney is a fishing village DOWN Bangor Abbey. which is owned and maintained by BT23 4SJ The area around Scrabo was The voyage proved unsuccessful with the National Trust. Close by is a place quarried for many years and this began 1 fierce storms forcing the ship to return 2 called Newcastle which was the landing 3 with a family called the Andersons. The to Ulster. spot for Sir Thomas Smith, the English stone was renowned and used in many Each year the event forms part of the Secretary of State who was ordered by distant locations. 2 NORTH DOWN MUSEUM, local events programme at Cockle Row 13 MARKET CROSS BT23 7HX Elizabeth I to try and establish the area. 25 HOLYWOOD PRIORY & BANGOR CASTLE & Cottages, Cottages open weekends & PRIORY BT23 7NX MAYPOLE 30 COMBER TOWN 19 BANGOR ABBEY from Easter - June and daily June - The Market Cross was built by Hugh QUINTIN CASTLE Priory corner of High Street and BT23 5DU The development of Down Co. in tours Sept, 11-5pm. Montgomery and the design was based BT22 1QB Quintin Castle was owned Bangor Road, Holywood, BT18 9AB Comber meant a time of co-operation Info: www.northdowntourism.com upon one which existed in Edinburgh. by the Savage family who came to The priory may date back as far as for James Hamilton and Hugh driving audio Ulster-Scots The cross represented what the Ireland with DeCourcy.