181 Chapter Five Back to the Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special Programs 215 345 6789

County Theater 79 PreviewsMARCH – MAY 2012 DAMSELS IN DISTRESS DAMSELS INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTY T HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. How can you support ADMISSION COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER General ..............................................................$9.75 Be a member. Members ...........................................................$5.00 Become a member of the nonprofit County Theater and Seniors (62+) show your support for good Students (w/ID) & Children (<18). ..................$7.25 films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a member- Matinees ship form or join on-line. Your financial support is tax-deductible. Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 Make a gift. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .......................................$7.25 Your additional gifts and support make us even better. Your Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ..........................$5.00 donations are fully tax-deductible. And you can even put your Affiliated Theaters Members* .............................$6.00 name on a bronze star in the sidewalk! You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. Contact our Business Office at (215) 348-1878 x117 or at The above ticket prices are subject to change. [email protected]. Be a sponsor. *Affiliated Theaters Members Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange The County Theater, the Ambler Theater, and the Bryn Mawr Film for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety Institute have reciprocal admission benefits. Your membership will of ways – on our movie screens, in our brochures, and on our allow you $6.00 admission at the other theaters. -

Advancedaudioblogs1#1 Top10israelitouristdestinations

LESSON NOTES Advanced Audio Blog S1 #1 Top 10 Israeli Tourist Destinations: The Dead Sea CONTENTS 2 Hebrew 2 English 3 Vocabulary 4 Sample Sentences 4 Cultural Insight # 1 COPYRIGHT © 2013 INNOVATIVE LANGUAGE LEARNING. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. HEBREW .1 . .2 4 0 0 - , . , . . . , .3 . . , 21 . . , . , , .4 . ; . 32-39 . . 20-32 , . ," .5 . , ENGLISH 1. The Dead Sea CONT'D OVER HEBR EW POD1 0 1 . C OM ADVANCED AUDIO BLOG S 1 #1 - TOP 10 IS RAELI TOURIS T DESTINATIONS: THE DEAD S EA 2 2. The miracle known as the Dead Sea has attracted thousands of people over the years. It is located near the southern area of the Jordan valley. The salt-rich Dead Sea is the lowest point on the earth's surface, being 400 meters below sea level. The air around the Dead Sea is unpolluted, dry, and pollen-free with low humidity, providing a naturally relaxing environment. The air in the region has a high mineral content due to the constant evaporation of the mineral rich water. 3. The Dead Sea comes in the list of the world's greatest landmarks, and is sometimes considered one of the Seven Wonders of the World. People usually miss out on this as they do not realize the importance of its unique contents. The Dead Sea has twenty-one minerals which have been found to give nourishment to the skin, stimulate the circulatory system, give a relaxed feeling, and treat disorders of the metabolism and rheumatism and associate pains. The Dead Sea mud has been used by people all over the world for beauty purposes. -

Beth Tzedec Congregation Tenth Annual Jewish Film Festival

BETH TZEDEC CONGREGATION TENTH ANNUAL JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL NOVEMBER 6 - 28, 2010 • CALGARY • ALBERTA BETH TZEDEC CONGREGATION TENTH ANNUAL JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL Proud to be a Sponsor of the SHALOM Welcome to the 10th Annual Beth Tzedec Jewish Film Festival – our 10th year of bringing the community together to explore and celebrate the richness and diversity of TENTH ANNUAL our Jewish world through the magical lens of cinema. This year’s exciting selection of films will take us on an eye-opening journey around the globe – from far-away places BETH TZEDEC CONGREGATION like Kazakhstan and South Africa to Argentina, Germany, the Czech Republic and Israel – and even into the heights of outer space. JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL Among our special guests this year, we are delighted to welcome six-time Emmy Award winning filmmaker Dan Cohen, director of An Article of Hope; Amir R. Gissin, Consul I. KARL GUREVITCH z”l General of Israel; Shlomi Eldar, director of the critically acclaimed Precious Life; and Dr. Izzeldin Abuelaish, a 2010 Nobel Peace Prize nominee and author of the book I Shall Not BENJAMIN L. GUREVITCH (retired) Hate: A Gaza Doctor’s Journey. LOUIS FABER z”l We are proud, this year, to introduce a new element to our festival: the Student Film Showcase, which will offer a forum for showcasing the talent, creativity and filmmaking skills of Grade 9 students of the Calgary Jewish Academy. And we are delighted to DAVID M. BICKMAN have worked with a newly-formed group called The Russian Speaking Jews of Calgary, who will be co-sponsoring a special evening dedicated to Russian-themed films. -

Course Description Fall 2013

COURSE DESCRIPTION FALL 2013 TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY TEL AVIV UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL STUDY ABROAD ‐ FALL SEMESTER 2013 COURSE DESCRIPTION MAIN OFFICE UNITED STATES CANADA The Carter Building , Room 108 Office of Academic Affairs Lawrence Plaza Ramat Aviv, 6997801, Israel 39 Broadway, Suite 1510 3130 Bathurst Street, Suite 214 Phone: +972‐3‐6408118 New York, NY 10006 Toronto, Ontario M6A 2A1 Fax: +972‐3‐6409582 Phone: +1‐212‐742‐9030 [email protected] [email protected] Fax: +1‐212‐742‐9031 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL.TAU.AC.IL 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ■ FALL SEMESTER 2013 DATES 3‐4 ■ ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS 6‐17 O INSTRUCTIONS FOR REGISTRATION 6‐7 O REGULAR UNIVERSITY COURSES 7 O WITHDRAWAL FROM COURSES 8 O PASS/FAIL OPTION 8 O INCOMPLETE COURSES 8 O GRADING SYSTEM 9 O CODE OF HONOR AND ACADEMIC INTEGRITY 9 O RIGHT TO APPEAL 10 O SPECIAL ACCOMMODATIONS 10 O HEBREW ULPAN REGULATIONS 11 O TAU WRITING CENTER 11‐12 O DESCRIPTION OF LIBRARIES 13 O MOODLE 13 O SCHEDULE OF COURSES 14‐16 O EXAM TIMETABLE 17 ■ TRANSCRIPT REQUEST INSTRUCTIONS 18 ■ COURSE DESCRIPTIONS 19‐97 ■ REGISTRATION FORM FOR STUDY ABROAD COURSES 98 ■ EXTERNAL REGISTRATION FORM 99 2 FALL SEMESTER 2013 IMPORTANT DATES ■ The Fall Semester starts on Sunday, October 6th 2013 and ends on Thursday, December 19th 2013. ■ Course registration deadline: Thursday, September 8th 2013. ■ Class changes and finalizing schedule (see hereunder): October 13th – 14th 2013. ■ Last day in the dorms: Sunday, December 22nd 2013. Students are advised to register to more than the required 5 courses but not more than 7 courses. -

Operation Pillar of Defense 1 Operation Pillar of Defense

Operation Pillar of Defense 1 Operation Pillar of Defense Operation Pillar of Defense Part of Gaza–Israel conflict Iron Dome launches during operation Pillar of Defense Date 14–21 November 2012 Location Gaza Strip Israel [1] [1] 30°40′N 34°50′E Coordinates: 30°40′N 34°50′E Result Ceasefire, both sides claim victory • According to Israel, the operation "severely impaired Hamas's launching capabilities." • According to Hamas, their rocket strikes led to the ceasefire deal • Cessation of rocket fire from Gaza into Israel. • Gaza fishermen allowed 6 nautical miles out to sea for fishing, reduced back to 3 nautical miles after 22 March 2013 Belligerents Israel Gaza Strip • Hamas – Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades • PIJ • PFLP-GC • PFLP • PRC • Al-Aqsa Martyrs' Commanders and leaders Operation Pillar of Defense 2 Benjamin Netanyahu Ismail Haniyeh Prime Minister (Prime Minister of the Hamas Authority) Ehud Barak Mohammed Deif Minister of Defense (Commander of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades) Benny Gantz Ahmed Jabari (KIA) Chief of General Staff (Deputy commander of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades) Amir Eshel Ramadan Shallah Air Force Commander (Secretary-General of Palestinian Islamic Jihad) Yoram Cohen Abu Jamal Director of Israel Security Agency (Shin Bet) (spokesperson of the Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades) Strength Israeli Southern Command and up to 75,000 reservists 10,000 Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades 8,000 Islamic Jihad Unknown for the rest 10,000 Security forces. Casualties and losses 2 soldiers killed. Palestinian figures: 20 soldiers wounded. 55 -

Israeli Film Fest Returns Jan. 16, 23 Interfaith Panel at TI to Examine

January 2010 NoFebruaryvember 20062007 Tevet/Shevat 5770 Heshvan/KisleShevat/Adar v 5767 5767 2200 Baltimore Road •• Rockville, Rockville, Maryland Maryland 20850 20851 www.tikvatisrael.org VolumeVolume 41 •• NumberNumber 1 It’sFrom Show the Time!President’ Israelis FilmPerspective Fest Returns Jan. 16, 23 Weekly Religious Services Weekly Religious Services The.annual.Israeli.Film.Festival.at.Tikvat.Israel.will.feature.a.pair.of.movies.created.by. This new and handsome bulletin format that we will succeed more than we will Joseph.Cedar,.a.decorated.Israeli.film.director. Monday..........6:45.a.m........... 7:30.p.m. is a fortuitous metaphor for the many changes fail. We will witness the vibrant growth of Monday ....... 6:45 a.m. ........ 7:30 p.m. The.two.screenings.are.“Time.of.Favor”.on.Jan..16.and.“Campfire”.on.Jan..23..Both. Tuesday.................................. 7:30.p.m. that Tikvat Israel Congregation will be our community that some don’t expect, but films.will.begin.at.7:45.p.m..Tickets.are.$10.per.film.for.a.TI.member,.$12.for.a.non- Tuesday ................................. 7:30 p.m. experiencing this year. Rori Pollak will be that we all want. This has been my philosophy Wednesday............................. 7:30.p.m. [email protected]. joining us in June as new director of the and approach towards my own career as a ThursdayWednesday....................................6:45.a.m........... 7:307:30. p.m. Cedar.received.international.attention.with.the.release.of.his.2007.film.“Beaufort”. Broadman-Kaplan Early Childhood Center. scientist, co-chair of the AEC, and now as Friday.............6:45.a.m.......................... -

TFL Extended – TV Series 12-16 February 2020 TFL EXTENDED HEAD of STUDIES

TFL Extended – TV Series 12-16 February 2020 TFL EXTENDED HEAD OF STUDIES Eilon Ratzkovsky Israel • Producer TFL EXTENDED – TV SERIES TUTORS Marietta von Hausswolff Eszter Angyalosy von Baumgarten Hungary • Scriptwriter, Sweden • Scriptwriter, Story Editor Story Editor Rasmus Horskjær Chiara Laudani Denmark • Scriptwriter, Italy • Scriptwriter, Story Editor Story Editor P. 2 Arca Genesis P. 15 Tenure P. 3 Chess P. 16 The Bridge P. 4 Dr. End P. 17 The Comedy of Time P. 5 Flatmates P. 18 The Ghosts of Molly Keenan P. 6 Fuxthaler P. 19 The Red Princess P. 7 How to Be P. 20 The Rule P. 8 Limboland P. 21 The Umbrella P. 9 Number 61 P. 22 Tinika P. 10 Parousia Second Coming P. 23 Ultima Date P. 11 Pyramid P. 24 Unholy Island P. 12 Sauble B**ch P. 25 Video On Demand VOD P. 13 Sekste P. 26 Wien 1913 P. 14 Shadow Man Arca Genesis ARCA GENESIS is a spaceship, a fringe science project and the last chance for the human race to survive the death of planet Earth. After 1400 years it Roberto Costantini almost reached its destination: Scriptwriter • Italy the blue planet Aquos. 13 years ago, AG1, the artificial Roberto Costantini was born in 1972 in Foligno and intelligence that manages the has a background in philosophy and cinema. He spaceship gave birth to the attended masterclasses and training programmes only three passengers of the in directing and screenwriting with Giorgio Arlorio, ship: Broll, Nina and Liv. They Vincenzo Cerami, Susanna Styron and Leonardo are meant to be the refounders Staglianò, among others. -

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS

2012 Twenty-Seven Years of Nominees & Winners FILM INDEPENDENT SPIRIT AWARDS BEST FIRST SCREENPLAY 2012 NOMINEES (Winners in bold) *Will Reiser 50/50 BEST FEATURE (Award given to the producer(s)) Mike Cahill & Brit Marling Another Earth *The Artist Thomas Langmann J.C. Chandor Margin Call 50/50 Evan Goldberg, Ben Karlin, Seth Rogen Patrick DeWitt Terri Beginners Miranda de Pencier, Lars Knudsen, Phil Johnston Cedar Rapids Leslie Urdang, Dean Vanech, Jay Van Hoy Drive Michel Litvak, John Palermo, BEST FEMALE LEAD Marc Platt, Gigi Pritzker, Adam Siegel *Michelle Williams My Week with Marilyn Take Shelter Tyler Davidson, Sophia Lin Lauren Ambrose Think of Me The Descendants Jim Burke, Alexander Payne, Jim Taylor Rachael Harris Natural Selection Adepero Oduye Pariah BEST FIRST FEATURE (Award given to the director and producer) Elizabeth Olsen Martha Marcy May Marlene *Margin Call Director: J.C. Chandor Producers: Robert Ogden Barnum, BEST MALE LEAD Michael Benaroya, Neal Dodson, Joe Jenckes, Corey Moosa, Zachary Quinto *Jean Dujardin The Artist Another Earth Director: Mike Cahill Demián Bichir A Better Life Producers: Mike Cahill, Hunter Gray, Brit Marling, Ryan Gosling Drive Nicholas Shumaker Woody Harrelson Rampart In The Family Director: Patrick Wang Michael Shannon Take Shelter Producers: Robert Tonino, Andrew van den Houten, Patrick Wang BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE Martha Marcy May Marlene Director: Sean Durkin Producers: Antonio Campos, Patrick Cunningham, *Shailene Woodley The Descendants Chris Maybach, Josh Mond Jessica Chastain Take Shelter -

Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: the Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films ot Facilitate Dialogue Elana Shefrin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Shefrin, Elana, "Re-Mediating the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The Use of Films to Facilitate Dialogue." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/14 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RE-MEDIATING THE ISRAELI-PALESTINIAN CONFLICT: THE USE OF FILMS TO FACILITATE DIALOGUE by ELANA SHEFRIN Under the Direction of M. Lane Bruner ABSTRACT With the objective of outlining a decision-making process for the selection, evaluation, and application of films for invigorating Palestinian-Israeli dialogue encounters, this project researches, collates, and weaves together the historico-political narratives of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the artistic worldviews of the Israeli and Palestinian national cinemas, and the procedural designs of successful Track II dialogue interventions. Using a tailored version of Lucien Goldman’s method of homologic textual analysis, three Palestinian and three Israeli popular film texts are analyzed along the dimensions of Historico-Political Contextuality, Socio- Cultural Intertextuality, and Ethno-National Textuality. Then, applying the six “best practices” criteria gleaned from thriving dialogue programs, coupled with the six “cautionary tales” criteria gleaned from flawed dialogue models, three bi-national peacebuilding film texts are homologically analyzed and contrasted with the six popular film texts. -

Pressed Minority, in the Diaspora

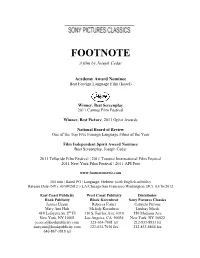

FOOTNOTE A film by Joseph Cedar Academy Award Nominee Best Foreign Language Film (Israel) Winner, Best Screenplay 2011 Cannes Film Festival Winner, Best Picture, 2011 Ophir Awards National Board of Review One of the Top Five Foreign Language Films of the Year Film Independent Spirit Award Nominee Best Screenplay, Joseph Cedar 2011 Telluride Film Festival | 2011 Toronto International Film Festival 2011 New York Film Festival | 2011 AFI Fest www.footnotemovie.com 105 min | Rated PG | Language: Hebrew (with English subtitles) Release Date (NY): 03/09/2012 | (LA/Chicago/San Francisco/Washington, DC): 03/16/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Hook Publicity Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Jessica Uzzan Rebecca Fisher Carmelo Pirrone Mary Ann Hult Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 419 Lafayette St, 2nd Fl 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10003 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 [email protected] 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel [email protected] 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax 646-867-3818 tel SYNOPSIS FOOTNOTE is the tale of a great rivalry between a father and son. Eliezer and Uriel Shkolnik are both eccentric professors, who have dedicated their lives to their work in Talmudic Studies. The father, Eliezer, is a stubborn purist who fears the establishment and has never been recognized for his work. Meanwhile his son, Uriel, is an up-and-coming star in the field, who appears to feed on accolades, endlessly seeking recognition. Then one day, the tables turn. When Eliezer learns that he is to be awarded the Israel Prize, the most valuable honor for scholarship in the country, his vanity and desperate need for validation are exposed. -

Jewish Family Services Update

L’CHAYIM www.JewishFederationLCC.org Vol. 43, No. 12 n August 2021 / 5781 A message from Alan Isaacs, A message from Barbara Siegel Federation Executive Director & Sherri Zucker, Co-Presidents ay 2022 will mark nearly 15 is reinforced by the frm belief that n behalf of the Federation’s sition and we are embracing the oppor- of some of the most fulfll- the Federation’s leadership is well- Board of Directors and the tunity to search for our next executive Ming years of my professional equipped to continue to advance the Oentire community, we want director. life. It will also signal a time of transi- Federation’s mission. I too will remain to thank Alan Isaacs for providing the We will work closely and consult tion for the Jewish Federation of Lee committed to the continued health and guidance and leadership that has been with The Jewish Federations of North and Charlotte Counties and me. At that welfare of our Federation and our com- so instrumental in our success for al- America throughout the process. A time, I will retire from my position at munity. most 15 years. Alan has informed us search committee has been formed and the Jewish Federation. I deeply appreciate the support that he would like to retire from his po- we have begun the process of fnding Between now and next May, the and guidance that I have received sition as our executive director in May the best executive for our community. Federation board, its leadership – Bar- from Federation leadership and staf, 2022. We know he is looking forward The board will announce our new pro- bara Siegel and Sherri Zucker – and I community members, colleagues and to playing more with his grandson and fessional leader in the coming months. -

University of Cambridge Tribute to the Jerusalem Sam

PROGRAM / SCHEDULE ALL SESSIONS WILL BEGIN AT 19:00 SESSION 1 THURSDAY - 21.1.16 changing israeli cinema from within Renen Schorr, founder-director of the Jerusalem Sam Spiegel Film School and The Mutes’ House, screening and conversation with award winning director Tamar Kay SESSION 2 THURSDAY - 28.1.16 footsteps in jerusalem Graduates homage (90’) to David Perlov’s iconic documentary, In Jerusalem fifty years later. Guest: Dr. Dan Geva SESSION 3 THURSDAY - 4.2.16 the conflict through the eyes of the jsfs students A collection of shorts (1994-2014), a retrospective curated by Prof. Richard Peña (82’) Guest: Yaelle Kayam SESSION 4 THURSDAY - 11.2.16 a birth of a filmmaker Nadav Lapid’s student and short films Guest: Nadav Lapid SESSION 5 THURSDAY - 18.2.16 the new normal haredi jew in israeli cinema Yehonatan Indurksy’s films Guest: Yehonatan Indursky SESSION 6 THURSDAY - 25.2.16 in search of a passive israeli hero Elad Keidan’s films Guest: Elad Keidan SESSION 7 THURSDAY - 3.3.16 the “mizrahi” (OF MIDDLE-EASTERN EXTRACTION) IS THE ARABIC JEW David Ofek’s films and television works Guest: David Ofek SESSION 8 THURSDAY - 10.3.16 revenge of the losers Talya Lavie’s films Guest: Talya Lavie UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE PRESENTS: BETWEEN Escapism and Strife A TRIBUTE TO THE JERUSALEM SAM SPIEGEL FILM SCHOOL In 1989 the Israeli film and television industry was changed forever when the first Israeli national film school was established in Jerusalem. Since then and for the past 25 years, the School, later renamed the Sam Spiegel Film School, graduated many of Israel’s leading film and television creators, who changed the film and television industry in Israel and were the engine for its renaissance, both in Israel and abroad.