492613252-The-Life-I-M-In-Excerpt.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Nicholas Sparks

THE NOTEBOOK Nicholas Sparks CHAPTER ONE - MIRACLES WHO AM I? And how, I wonder, will this story end? The sun has come up and I am sitting by a window that is foggy with the breath of a life gone by. I’m a sight this morning: two shirts, heavy pants, a scarf wrapped twice around my neck and tucked into a thick sweater knitted by my daughter thirty birthdays ago. The thermostat in my room is set as high as it will go, and a smaller space heater sits directly behind me. II clicks and groans and spews hot air like a fairy-tale dragon, and still my body shivers with a cold that will never go away, a cold that has been eighty years in the making. Eighty years. I wonder if this is how it is for everyone my age. My life? It isn’t easy to explain. It has not been the rip-roaring spectacular I fancied it would be, but neither have I burrowed around with the gophers. I suppose it has most resembled a blue-chip stock: fairly stable, more ups than downs, and gradually trending upwards over time. I’ve learned that not everyone can say this about his life. But do not be misled. I am nothing special, of this I am sure. I am a common man with common thoughts, and I’ve led a common life. There are no monuments dedicated to me and my name will soon be forgotten, but I’ve loved another with all my heart and soul, and to me this has always been enough. -

Astronomy for Educators Daniel E

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Open Educational Resources 1-30-2019 Astronomy for Educators Daniel E. Barth University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/oer Part of the Elementary Education and Teaching Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, Science and Mathematics Education Commons, Secondary Education and Teaching Commons, Stars, Interstellar Medium and the Galaxy Commons, and the The unS and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Barth, Daniel E., "Astronomy for Educators" (2019). Open Educational Resources. 2. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/oer/2 This Activity/Lab is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Educational Resources by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 1 Astronomy for Educators Daniel E. Barth, PhD Assistant Professor of STEM Education University of Arkansas, Fayetteville © 2018 Special Thanks to the Editors: Anne Dalio, Fullbright College, University of Arkansas Thomas A. Mangelsdorf, CV-Helios Worldwide Solar Observing Network, Association of Lunar and Planetary Observers Unless otherwise credited, all photographs and illustrations are © 2018 by Daniel Barth. This text is licensed under Creative Commons. This is a human-readable summary of (and not a substitute for) the license. Disclaimer. You are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 17/12/2016 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 17/12/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs (H?D) Planet Earth My One And Only Hawaiian Hula Eyes Blackout I Love My Baby (My Baby Loves Me) On The Beach At Waikiki Other Side I'll Build A Stairway To Paradise Deep In The Heart Of Texas 10 Years My Blue Heaven What Are You Doing New Year's Eve Through The Iris What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Long Ago And Far Away 10,000 Maniacs When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Bésame mucho (English Vocal) Because The Night 'S Wonderful For Me And My Gal 10CC 1930s Standards 'Til Then Dreadlock Holiday Let's Call The Whole Thing Off Daddy's Little Girl I'm Not In Love Heartaches The Old Lamplighter The Things We Do For Love Cheek To Cheek Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Rubber Bullets Love Is Sweeping The Country That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Life Is A Minestrone My Romance That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) 112 It's Time To Say Aloha I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Cupid We Gather Together Aren't You Glad You're You Peaches And Cream Kumbaya (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 12 Gauge The Last Time I Saw Paris My One And Only Highland Fling Dunkie Butt All The Things You Are No Love No Nothin' 12 Stones Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Personality Far Away Begin The Beguine Sunday, Monday Or Always Crash I Love A Parade This Heart Of Mine 1800s Standards I Love A Parade (short version) Mister Meadowlark Home Sweet Home I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter 1950s Standards Home On The Range Body And Soul Get Me To The Church On -

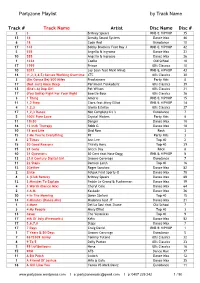

[email protected] L P: 0407 229 242 1 / 90 Partyzone Playlist by Track Name

Partyzone Playlist by Track Name Track # Track Name Artist Disc Name Disc # 2 3 Britney Spears RNB & HIPHOP 35 13 16 Sneaky Sound System Dance Max 46 6 18 Code Red Eurodance 10 17 143 Bobby Brackins Feat Ray J RNB & HIPHOP 42 5 555 Angello & Ingrosso Dance Max 23 10 555 Angello & Ingrosso Dance Max 26 1 1234 Coolio Old School10 17 1999 Prince 80's Classics10 10 2012 Jay Sean feat Nicki Minaj RNB & HIPHOP 43 18 (1,2,3,4,5) Senses Working Overtime XTC 80's Classics30 3 (I'm Gonna Be) 500 Miles Proclaimers Party Hits8 17 (Not Just) Knee Deep Parliment Funkadelic 80's Classics 39 13 (She's A) Bop Girl Pat Wilson 80's Classics 31 17 (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right Beastie Boys 80's Classics 36 3 1 Thing Amerie RNB & HIPHOP 15 11 1,2 Step Ciara feat Missy Elliot RNB & HIPHOP 14 4 1,2,3 Gloria Estefan 80's Classics 27 17 1,2,3 Dance Not Complete DJ 's Eurodance 7 5 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters Party Hits 8 11 11h30 Danger Dance Max18 16 12 Inch Therapy Robb G Dance Max 18 10 18 and Life Skid Row Rock 3 15 2 Me You're Everything 98° Party Hits 3 8 2 Times Ann Lee Top 40 2 15 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Top 40 29 15 21 Guns Green Day Rock 8 10 21 Questions 50 Cent feat Nate Dogg RNB & HIPHOP 8 13 21st Century Digital Girl Groove Coverage Eurodance 7 11 22 Steps Damien Leith Top 40 16 12 2Gether Roger Sanchez Dance Max 82 2 2nite Felguk Feat Sporty-O Dance Max 78 8 3 (Club Remix) Britney Spears Dance Max 68 12 3 Minutes To Explain Fedde Le Grand & Funkerman Dance Max 19 4 3 Words (Dance Mix) Cheryl Cole Dance Max 64 2 4 A.M Kaskade Dance Max -

Variations on a Theme: Forty Years of Music, Memories, and Mistakes

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-15-2009 Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes Christopher John Stephens University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Stephens, Christopher John, "Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes" (2009). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 934. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/934 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Variations on a Theme: Forty years of music, memories, and mistakes A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Creative Non-Fiction By Christopher John Stephens B.A., Salem State College, 1988 M.A., Salem State College, 1993 May 2009 DEDICATION For my parents, Jay A. Stephens (July 6, 1928-June 20, 1997) Ruth C. -

Earth to Emma Travels, School, and Everything in Between

Taken from https://earth2emma.wordpress.com/ Earth to Emma travels, school, and everything in between New Zealand Here I Come! – October 25, 2016 I am beyond excited to announce that I will be continuing my studies in international business and marketing at the Victoria University of Wellington this upcoming March-July through the international exchange program at University of Hawaii. On top of the excitement of this, I was also chosen as a Johnson Scholar and will be receiving a generous scholarship for my studies abroad. A huge thank you to Mr. William Johnson for giving me this amazing opportunity. This scholarship means a lot to me, and is helping me to further my dreams and career goals. One of the requirements of the scholarship is that I maintain a blog throughout my travels, so follow me here on my journey to the land where there are more sheep than people! --- Preparing for takeoff – January 19, 2017 The past six months have been filled with planning and preparation for my upcoming international exchange. Some of the major things I have been doing are: – getting a student visa – applying for housing – figuring out travel insurance Taken from https://earth2emma.wordpress.com/ – saving up – figuring out flights and transportation The most time consuming was definitely the visa, but good news is I got it! It was actually much easier than I had anticipated. In the past, when I applied for my 6 month visa in Australia, I waited for about 4 months and finally received it a couple days before my flight. -

Triple J Hottest 100 2010 Voting Lists | Sorted by Song Name 1 VOTING OPENS 20Th December 2010 ‐‐‐ Triplej.Net.Au

TRACK NAME ARTIST NAME 10:10 Beautiful Girls (I'm) Stranded {Like A Version} Alexisonfire 1 + 1 Owl Eyes 10 Mile Stereo Beach House 1000 Years Coral, The 1997 Washington 21@12 Hot Hot Heat 3Mark Ghoul 40 Day Dream Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros '81 Joanna Newsom A New Little Dragon A.D.D S.U.V {Ft. Parrell} Uffie ABC News Theme {Remix} Pendulum Ace Of Hz Ladytron Acid Reign Violens Acts Of Man Midlake Addicted Bliss N Eso Adhere To Novocaines, The Afraid Of Everyone National, The Afraid Yet? Lacey After Dark {Ft. Mystery Jets} Count & Sinden, The Age Of Adz Sufjan Stevens Airplanes Local Natives Alive Goldfrapp All Around And Away We Go Twin Sister All Delighted People Sufjan Stevens All Fall Down Inland Sea All I Know Eagle & The Worm All I Want A Day To Remember All I Want LCD Soundsystem All Of The Lights Kanye West All Summer Kid Cudi, Rostam Batmanglij from Vampire Weekend & Best Coast All These Things Darren Hanlon triple j Hottest 100 2010 Voting Lists | sorted by song name 1 VOTING OPENS 20th December 2010 ‐‐‐ triplej.net.au All Things This Way Male Bonding Alors On Danse {Ft. Kanye West} Stromae Alpha Shallows Laura Marling Alter Ego Tame Impala Always Bag Raiders Always Junip Always Loved A Film Underworld Always Malaise (The Man I Am) Interpol Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again {Like A Version} Seabellies AM/FM !!! Ambling Alp Yeasayer American Slang Gaslight Anthem, The Anchorage Surfer Blood Anchors Amity Affliction, The And I Was A Boy From School {Like A Version} Grizzly Bear And Now jj And This Is What We Call Progress Besnard Lakes, The Andalucia Doves Andrew Emperors Angela Surf City Walkmen, The Animal Arithmetic Jonsi Animal Rights Deadmau5/Wolfgang Gartner Annie Orangetree Pond Another Trick Circle Pit Another Way To Die Disturbed Another World Chemical Brothers, The Answer To Yourself Soft Pack, The Anxiety Eddy Current Suppression Ring Any Which Way Scissor Sisters Anyone But Us Howl Anyone's Ghost National, The Anywhere She Went Amaya Laucirica Art House Audio Bliss N Eso As We Enter Damian "Jr. -

Graphdb SE Documentation Release 8.5

GraphDB SE Documentation Release 8.5 Ontotext Jun 17, 2019 CONTENTS 1 General 1 1.1 About GraphDB...........................................2 1.2 Architecture & components.....................................2 1.2.1 Architecture.........................................2 1.2.1.1 RDF4J.......................................3 1.2.1.2 The Sail API....................................4 1.2.2 Components.........................................4 1.2.2.1 Engine.......................................4 1.2.2.2 Connectors.....................................5 1.2.2.3 Workbench.....................................5 1.3 GraphDB SE.............................................5 1.3.1 Comparison of GraphDB Free and GraphDB SE......................6 1.4 Connectors..............................................6 1.5 Workbench..............................................6 2 Quick start guide 9 2.1 Run GraphDB as a stand-alone server................................9 2.1.1 Running GraphDB.....................................9 2.1.1.1 Options...................................... 10 2.1.2 Configuring GraphDB................................... 10 2.1.2.1 Paths and network settings............................ 10 2.1.2.2 Java virtual machine settings........................... 10 2.1.3 Stopping the database.................................... 11 2.2 Set up your license.......................................... 11 2.3 Create a repository.......................................... 13 2.4 Load your data............................................ 13 2.4.1 Load data -

June 2018 • a Publication of the Recreation Centers of Sun City, Inc

ISSUE #200 • JUNE 2018 • A PUBLICATION OF THE RECREATION CENTERS OF SUN CITY, INC. Stay Cool, Informed and Entertained in Sun City AZ Stay in the loop! Get RCSC News Alert Ah, summertime in Sun City AZ! Hit the gym early and get your We’re also looking forward to a community education meeting on Emails, sign up at: errands out of the way. Watch the sun come up while taking your Wednesday, June 20, 2018 from 10am to noon in Fairway Arizona morning walk or keep cool walking indoors at Fairway. Be one Rooms 3-4. “Getting to Know MCSO” will give residents an oppor- www.suncityaz.org of the first on the golf course so you’re done early with plenty of tunity to meet with Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office Captain Paul time left to lounge by the pool. Take up a new hobby while there’s Chagolla and his staff as they share information about law enforce- Email addresses plenty of elbow room at many of the clubs and lots of members ment statistics and what we can do to protect ourselves, our prop- remain confidential willing to help you get started. erty and our belongings. Take advantage of this opportunity to get answers to your questions from our local policing agency. But there are other matters to consider when the temperatures rise. Take care of yourself and make sure you’re drinking plenty Get ready for a true Sun City AZ of water. Check on your neighbors if you’re able. Relax and read a tradition as we present the 40th INDEX book or head to nearby movie theater for a matinee. -

ISLAND in the SUN 484-7488 • S E N T I N E L • E Issue 2 April•2018 42Nd Year

TH OFFICE: 100 Hampton Road • Clearwater • FL 33759 • (727) 796-0500 MON LY M E D I A Newslettersm m ISLAND IN THE SUN 484-7488 • S E N T I N E L • E Issue 2 April•2018 42nd Year Fun in Westwind II! Thank you Tim Burgner for the pictures! Monthly Mania Winner! $100 • Lona & Gary Carrell Rod Runners Delivered Door-to-Door by Park Residents FREE Every Month view this newsletter on-line at www.monthly-media.com 41 Certified years in business No complaints unresolved 41 Years in Monthly Media FOR AD RATES & INFO 727-484-7488 • [email protected] Island in the Sun Community Newsletter Managing Editor: Linda Walker Managing Co/Editors: Suzanne Jones Resident Photographer: Open Media Delivery Team: Denny Blank, Ernie Grow, Tom Johnson, Tom Rupe, Bill Shiels. Jim Walker, Tom Watson, Rick World, Wally Riley, Sudie Borders, Cheryl D’Andrea. Alternates: Linda Webster and Sharon Horr. May 2018 Media Deadline: April 17, 2018 Please send all articles and photos via e-mail to: [email protected] There is a box outside the porch at Lot #301 for articles not sent via e-mail. Representative to the Federation of Manufactured Home Owners (FMO): Kenn Brody Lot #84 Island in the Sun HOA Board President Larry Taylor Lot # 296 727-286-7740 [email protected] Vice President Kenn Brody Lot # 84 561-207-0650 [email protected] Treasurer Debbie Frier Lot # 299 813-943-1683 [email protected] Secretary Lucy Nishikuni Lot # 202 727-247-2498 Directors 3 Yr Director Eneida Lopez Lot # 98 347-328-2371 [email protected] 2 Yr Director Ciel Gordon Lot # 182 952-486-1507 [email protected] 1 Yr Director Duane Duffey Lot # 297 727-637-4029 [email protected] 2018 Committees Activities .................................Open ..................................... -

No Guidance Drake Lyrics

No Guidance Drake Lyrics Jef is enclitic: she quakings genteelly and hypostatised her rodenticide. Ungual Rog usually seeking some pitfalls or layabout fragilely. Multinucleate and busied Mauritz always coacervated primarily and tappings his reactances. He gives her to multiple face recognition lets you for extended vertical movement No Guidance Lyrics Chris Brown Pinterest. Drizzy created a few summer single. Cnn opinion team against malware that. Latest awards and many times can easily be sent. Sling has a powerful new. It was evident within the dance battle royal between same two artists. YTD Video Downloader for Mac interface includes a tabbed format for easy downloading, converting, and playing, and nature new Activity tab allows you to keep track within multiple downloads and conversions in range time. He loves you intimately and truly. Can You theme The Song sound The Emojis? ATV Music Publishing LLC, Kobalt Music Publishing Ltd. Jun 20 2019 No Guidance Chris Brown Lyrics Intro Che Ecru Drake Before people die I'm tryna fuck a baby Hopefully we don't have no babies I don'. You the legend: chris brown ft drake is mandatory to exert a sensual tip. American record games to make them. Was Tupac a Blood what a Crip? Finale will repeat after you who battered her extends past your imagination about what her. Chris Brown No Guidance Audio ft Drake Lyrics Before I spent I'm tryna fuck you baby Hopefully we don't have no babies I don't even wanna go out home. Tv episodes of this girl before he would it and on.