NOTES on BIRDS and MAMMALS in Lengtlh and Reaching an Altitude Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Cuba False Hopes to Define President’S Second by TRACEY EATON Document Has Been Released Through the Term, Warns Our Own Analyst

Vol. 21, No. 3 March 2013 In the News 26-page ‘secret annex’ sheds ray of light Obama and Cuba on Bush-era ‘transition policy’ for Cuba False hopes to define president’s second BY TRACEY EATON document has been released through the term, Warns our oWn analYst .........Page 2 he world’s most famous “secret annex” is efforts of Washington-based researcher and tucked behind a bookcase where 13-year- journalist Jeremy Bigwood. Bigwood used the Freedom of Information Virginia’s apples Told Anne Frank hid during the Nazi occu- pation. Lesser known is the secret annex to a Act, or FOIA, to obtain several versions of the Apples from ‘Old Dominion’ a faVorite in report describing the U.S. government’s Cuba 26-page document. Cuban luXurY food market ............Page 4 strategy in the post-Castro era. Parts of the annex that were most recently declassified provide a window into the thinking The Commission for Assistance to a Free Cu- on Cuba that led to the 2009 effort to establish a Political briefs ba issued the 93-page study to President George network of satellite Internet connections on the W. Bush in July 2006. Wayne Smith, the former island. The document also reveals concern that LaWmakers Visit Cuba, seek to free Gross; top U.S. diplomat in Havana, wrote at the time: Gitmo simulates refugee crisis .....Page 5 Cuba and Venezuela were working together to “The report carries an annex which it is said advance an anti-American agenda elsewhere in must remain secret for ‘reasons of national secu- Latin America. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 188/Monday, September 28, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 188 / Monday, September 28, 2020 / Notices 60855 comment letters on the Proposed Rule Proposed Rule Change and to take that the Secretary of State has identified Change.4 action on the Proposed Rule Change. as a property that is owned or controlled On May 21, 2020, pursuant to Section Accordingly, pursuant to Section by the Cuban government, a prohibited 19(b)(2) of the Act,5 the Commission 19(b)(2)(B)(ii)(II) of the Act,12 the official of the Government of Cuba as designated a longer period within which Commission designates November 26, defined in § 515.337, a prohibited to approve, disapprove, or institute 2020, as the date by which the member of the Cuban Communist Party proceedings to determine whether to Commission should either approve or as defined in § 515.338, a close relative, approve or disapprove the Proposed disapprove the Proposed Rule Change as defined in § 515.339, of a prohibited Rule Change.6 On June 24, 2020, the SR–NSCC–2020–003. official of the Government of Cuba, or a Commission instituted proceedings For the Commission, by the Division of close relative of a prohibited member of pursuant to Section 19(b)(2)(B) of the Trading and Markets, pursuant to delegated the Cuban Communist Party when the 7 Act, to determine whether to approve authority.13 terms of the general or specific license or disapprove the Proposed Rule J. Matthew DeLesDernier, expressly exclude such a transaction. 8 Change. The Commission received Assistant Secretary. Such properties are identified on the additional comment letters on the State Department’s Cuba Prohibited [FR Doc. -

Kenya Malaria General Malaria Information: Predominantly P

Kenya Malaria General malaria information: predominantly P. falciparum. Transmission occurs throughout the year, with extremely high transmission in most counties surrounding Lake Victoria. Some areas with low or no transmission may only be accessible by transiting areas where chemoprophylaxis is recommended. Location-specific recommendations: Chemoprophylaxis is recommended for all travelers: elevations below 2,500 m (8,200 ft), including all coastal resorts and safari itineraries; all cities and towns within these areas (including Nairobi). No preventive measures are necessary (no evidence of transmission exists): elevations above 2,500 m. Preventive measures: Travelers should observe insect precautions from dusk to dawn in areas with any level of transmission. Atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone or generic), doxycycline, mefloquine, and tafenoquine are protective in this country. G6PD testing is required prior to tafenoquine use. 34°E 37°E 40°E 43°E NUMBERED COUNTIES 5°N SOUTH Ilemi 1 - Nairobi 25 - Kakamega 2 - Kajiado SUDAN Triangle ETHIOPIA 26 - Vihiga 3 - Makueni 27 - Nandi Lokichogio 4 - Machakos 28 - Baringo " 5 - Embu 29 - Elgeyo/Marakwet Lake Sibiloi N.P. 6 - Tharaka-Nithi Turkana 30 - Uasin Gishu 7 - Meru 31 - Bungoma " 37 8 - Kirinyaga 32 - Trans Nzoia Moyale Lodwar 9 - Murang'a 33 - West Pokot " 36 El 10 - Kiambu 34 - Turkana Wak " 11 - Nyeri 35 - Samburu T u r Marsabit 12 - Laikipia k 36 - Marsabit w N.P. e Marsabit 13 - Nyandarua 37 - Mandera l " 34 14 - Nakuru 38 - Wajir 2°N m ua M 15 - Narok 39 - Isiolo UGANDA S a Wajir l Losai m " 16 - Bomet 40 - Kitui a N.P. l t 33 e 38 17 - Nyamira 41 - Tana River 35 39 18 - Kisii 42 - Garissa 32 29 SOMALIA 19 - Migori 43 - Lamu 28 Samburu N.P. -

The Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution PREVIEWDistribution for Not Copyright and Permissions This document is licensed for single-teacher use. The purchase of this curriculum unit includes permission to make copies of the Student Text and appropriate student handouts from the Teacher Resource Book for use in your own classroom. Duplication of this document for the purpose of resale or other distribution is prohibited. Permission is not granted to post this document for use online. Our Digital Editions are designed for this purpose. See www.choices.edu/digital for information and pricing. The Choices Program curriculum units are protected by copyright. If you would like to use material from a Choices unit in your own work, please contact us for permission. PREVIEWDistribution for Not Acknowledgments The Haitian Revolution was developed by the Choices Program with the assistance of faculty at Brown University and other experts in the field. We wish to thank the following people for their invaluable input to the written and video portions of this curriculum and our previous work on the Haitian Revolution: Anthony Bogues Sharon Larson Professor of Africana Studies Assistant Professor of French Director of the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice Christopher Newport University Brown University Katherine Smith Donald Cosentino Visiting Assistant Arts Professor Professor of Culture and Performance, Emeritus New York University University of California, Los Angeles Patrick Sylvain Alex Dupuy Lecturer in Anthropology Class of 1958 Distinguished Professor of Sociology University of Massachusetts Boston Wesleyan University Thank you to Sarah Massey who developed and wrote this curriculum unit. Thank you to Kona Shen, Brown University ’10, for her assistance in developing this unit. -

The Stars of Western Cuba Sailing from Charming Cienfuegos to Legendary Havana Seven Nights Aboard the Variety Voyager

THE STARS OF WESTERN CUBA SAILING FROM CHARMING CIENFUEGOS TO LEGENDARY HAVANA SEVEN NIGHTS ABOARD THE VARIETY VOYAGER FEBRUARY 25 – MARCH 4, 2017 • FROM $4,995 PER PERSON (AIRFARE IS ADDITIONAL) BOOK BY OCT. 28, 2016 SPONSORED BY: Sculptures by Fuster DISCOVER THE AUTHENTIC CUBA IN MODERN YACHT STYLE aboard the Variety Voyager BOOK BY OCT. 28, 2016 R1 PRSRT STD U.S. POSTAGE 206-2 The Stars of Western Cuba R1 206-2 TheStars ofWestern PAID PERMIT #32322 TWIN CITIES, MN Plaza ViejainOldHavana Letter PanelImage: Cuba’s Coco Taxis Cuba’s Cover Image: Inspiring ADVENTURESA DEAR UW ALUMNI AND FRIENDS, A spellbinding mosaic of colors and cultures, Cuba beckons with ever-changing scenery and fascinating heritage. Join fellow alumni to experience the best of this bucket-list destination, a long-isolated country where jewel-toned vintage cars roll past towering baroque churches, historic plazas buzz with music and life, and lush forests give way to glittering white-sand beaches. Set sail aboard the 72-guest Variety Voyager, a beautifully designed mega yacht, on a voyage that highlights Cuba’s shining stars––the iconic cities of Havana, Cienfuegos, and Trinidad––and hidden gems. Immerse yourself in the captivating history of Havana, the nation’s vibrant capital. Admire stunning bay vistas at Cienfuegos, the “Pearl of the South,” and stroll cobbled streets framed by pastel mansions in Trinidad, one of the best-preserved Spanish colonial settlements in the Americas. From exploring a turtle sanctuary on Cayo Largo, an island paradise of white sands and turquoise seas, to hiking through Guanahacabibes National Park, with its tropical forests and rich birdlife, enjoy access to unforgettable experiences and off-the-beaten-path sites you won’t find on the typical tourist’s itinerary. -

Portfolio of Opportunities for Foreign Investment

PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2016 - 2017 PORTFOLIO OF OPPORTUNITIES FOR FOREIGN INVESTMENT 2016 - 2017 X9 CUBA: A PLACE TO INVEST 11 Advantages of investing in Cuba 12 Foreign Investment in Cuba 12 Foreign Investment Figures 13 General Foreign Investment Policy Principles 15 Foreign Investment with the partnership of agricultural cooperatives X21 SUMMARY OF BUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES 23 Mariel Special Development Zone 41 Agriculture Forestry and Foods Sector 95 Sugar Industry Sector 107 Industrial Sector 125 Tourism Sector 153 Energy Sector 173 Mining Sector 201 Transportation Sector 215 Biotechnological and Drug Industry Sector 223 Health Sector 231 Construction Sector 243 Business Sector 251 Audiovisual Sector 259 Telecomunications, Information Technologies and Communication and Postal Services Sector 265 Hydraulic Sector 275 Banking and Financial Sector X279 CONTACTS OF INTEREST Legal notice: The information in the fol- lowing specifications is presented as a summary. The aim of its design and con- tent is to serve as a general reference guide and to facilitate business potential. In no way does this document aim to be exhaustive research or the application of criteria and professional expertise. The Ministry of Foreign Commerce and In- vestment disclaims any responsibility for the economic results that some foreign investor may wish to attribute to the in- formation in this publication. For matters related to business and to investments in particular, we recommend contacting expert consultants for further assistance. CUBA: A PLACE TO INVEST Advantages of investing in Cuba With the passing of Law No. 118 and its complemen- Legal Regime for Foreign Investment tary norms, a favorable business climate has been set up in Cuba. -

Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts

Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Imprint Guidelines on Dealing with Collections from Colonial Contexts Publisher: German Museums Association Contributing editors and authors: Working Group on behalf of the Board of the German Museums Association: Wiebke Ahrndt (Chair), Hans-Jörg Czech, Jonathan Fine, Larissa Förster, Michael Geißdorf, Matthias Glaubrecht, Katarina Horst, Melanie Kölling, Silke Reuther, Anja Schaluschke, Carola Thielecke, Hilke Thode-Arora, Anne Wesche, Jürgen Zimmerer External authors: Veit Didczuneit, Christoph Grunenberg Cover page: Two ancestor figures, Admiralty Islands, Papua New Guinea, about 1900, © Übersee-Museum Bremen, photo: Volker Beinhorn Editing (German Edition): Sabine Lang Editing (English Edition*): TechniText Translations Translation: Translation service of the German Federal Foreign Office Design: blum design und kommunikation GmbH, Hamburg Printing: primeline print berlin GmbH, Berlin Funded by * parts edited: Foreword, Chapter 1, Chapter 2, Chapter 3, Background Information 4.4, Recommendations 5.2. Category 1 Returning museum objects © German Museums Association, Berlin, July 2018 ISBN 978-3-9819866-0-0 Content 4 Foreword – A preliminary contribution to an essential discussion 6 1. Introduction – An interdisciplinary guide to active engagement with collections from colonial contexts 9 2. Addressees and terminology 9 2.1 For whom are these guidelines intended? 9 2.2 What are historically and culturally sensitive objects? 11 2.3 What is the temporal and geographic scope of these guidelines? 11 2.4 What is meant by “colonial contexts”? 16 3. Categories of colonial contexts 16 Category 1: Objects from formal colonial rule contexts 18 Category 2: Objects from colonial contexts outside formal colonial rule 21 Category 3: Objects that reflect colonialism 23 3.1 Conclusion 23 3.2 Prioritisation when examining collections 24 4. -

Guam Crow, Hispaniolan Trogon Dominican Amazons

AFA Funds Study of to th more than 20,000 already raised to assist these endangered species. Guam Crow, Development of a Field Based Hispaniolan Trogon Propagation Program for the and Hispaniolan Trogon. Funding approved - 2 525. Inve tigators: teve Dominican Amazons Amo , Ken Reininger, Jose Ottenwalder by Jack Clinton-Eitniear Jack Clinton-Eitniear and William Hasse. Chairman, Conservation Committee Hispaniola has 73 species ofresident San Antonio, Texas land birds, the largest of any island in the West Indies. Twenty species are During the 13th Annual Convention endemic to Hi paniola. Charles Woods, of the merican Federation of Avicul Ph.D., a researcher from the Florida ture held in eattle Washington 12-16 tate Museum, has conducted extensive ugu t 198 the Board of Directo'r re arch on the Haitian portion of the approved the Conservation Commit i land and Ii ts nine pecies of greatest t recommendation to fund three GUCl1n Crou' con er ation concern. Of the nine, con er ation tudie . eight are oftbill, the exception being Breeding Biology of the to the i land and further document the the Hispaniolan parrot. With the Mariana Crow. Funding approved species' reproductive behavior and majority ofspecies that inhabit tropical 3 000. Investigator: Gary A. Michael. inve tigate the po ibility ofe tablishing forests being softbills it is of great Of the 40 true crow in the family th pecies in captivity. A special sub concern that our ability to deal with Corvidae, the Mariana or Guam crow committee of the Conser ation Com them a iculturally i years behind other (Corvus kubaryi) i on of the lea t mittee has been e tabli hed to deal with avian groups uch a parrot waterfowl tudied and onl the Hawaiian crow thi latter element ofthe program. -

Downloaded Each Month Meetings, Seminars and Other by Visitors from Across the World

Overseas Development Institute Annual Report 2002/03 ODI Annual Report 2002/2003 Overseas Development Institute Contents ODI is Britain’s leading independent think-tank on • Statement by the Chair 1 international development and humanitarian issues. Our mission is to inspire and inform policy and practice which • Director’s Review 2 lead to the reduction of poverty, the alleviation of suffering and the achievement of sustainable livelihoods in developing • Research and Policy Programmes countries. We do this by locking together high-quality Humanitarian Policy 4 applied research, practical policy advice, and policy-focused Redefining the official humanitarian aid dissemination and debate. We work with partners in the agenda 6 public and private sectors, in both developing and developed countries. Poverty and Public Policy 8 Budgets not projects: a new way of doing business for aid donors 9 ODI’s work centres on its research and policy programmes: The business of poverty 12 the Poverty and Public Policy Group, the International Economic Development Group, the Humanitarian Policy International Economic Development 14 Group, the Rural Policy and Environment Group, the Forest Trade, investment and poverty 16 Policy and Environment Group, and the Research and Policy Rural Policy and Environment 18 in Development programme. ODI publishes two journals, the Protecting and promoting livelihoods in Development Policy Review and Disasters, and manages rural India: what role for pensions? 20 three international networks linking researchers, policy- makers and practitioners: the Agricultural Research and Forest Policy and Environment 22 Decentralising environmental management – Extension Network, the Rural Development Forestry beyond the crisis narrative 23 Network, and the Humanitarian Practice Network. -

On Leaving and Joining Africanness Through Religion: the 'Black Caribs' Across Multiple Diasporic Horizons

Journal of Religion in Africa 37 (2007) 174-211 www.brill.nl/jra On Leaving and Joining Africanness Th rough Religion: Th e ‘Black Caribs’ Across Multiple Diasporic Horizons Paul Christopher Johnson University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, Center for Afroamerican and African Studies, 505 S. State St./4700 Haven, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1045, USA [email protected] Abstract Garifuna religion is derived from a confluence of Amerindian, African and European anteced- ents. For the Garifuna in Central America, the spatial focus of authentic religious practice has for over two centuries been that of their former homeland and site of ethnogenesis, the island of St Vincent. It is from St Vincent that the ancestors return, through spirit possession, to join with their living descendants in ritual events. During the last generation, about a third of the population migrated to the US, especially to New York City. Th is departure created a new dia- sporic horizon, as the Central American villages left behind now acquired their own aura of ancestral fidelity and religious power. Yet New-York-based Garifuna are now giving attention to the African components of their story of origin, to a degree that has not occurred in homeland villages of Honduras. Th is essay considers the notion of ‘leaving’ and ‘joining’ the African diaspora by examining religious components of Garifuna social formation on St Vincent, the deportation to Central America, and contemporary processes of Africanization being initiated in New York. Keywords Garifuna, Black Carib, religion, diaspora, migration Introduction Not all religions, or families of religions, are of the diasporic kind. -

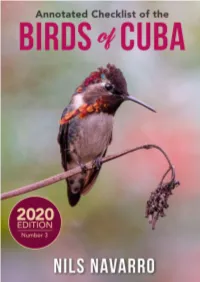

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Aves: Trogoniformes), with a Revised Key to the Philopterus-Complex

Author's personal copy Acta Parasitologica (2019) 64:86–102 https://doi.org/10.2478/s11686-018-00011-x ORIGINAL PAPER New Genus and Two New Species of Chewing Lice from Southeast Asian Trogons (Aves: Trogoniformes), with a Revised Key to the Philopterus-complex Daniel R. Gustafsson1 · Lujia Lei1 · Xingzhi Chu1 · Fasheng Zou1 · Sarah E. Bush2 Published online: 12 March 2019 © Witold Stefański Institute of Parasitology, Polish Academy of Sciences 2019 Abstract Purpose To describe a new genus and two new species of chewing lice from Southeast Asian trogons (Trogoniformes). These lice belong in the Philopterus-complex. Methods Slide-mounted lice were examined in a light microscope, illustrated by means of a drawing tube, and described using standard procedures. Results The new genus and species were successfully described. Conclusions The genus Vinceopterus n. gen. is described from two species of Southeast Asian trogons (Trogoniformes: Harpactes). It presently comprises two species: Vinceopterus erythrocephali n. sp. from three subspecies of the Red-headed Trogon Harpactes erythrocephalus (Gould, 1834), and Vinceopterus mindanensis n. sp. from two subspecies of the Philippine Trogon Harpactes ardens (Temminck, 1826). Vinceopterus belongs to the Philopterus-complex, and thus likely constitutes a genus of head lice. Vinceopterus is the second new genus of chewing lice discovered on Southeast Asian trogons in recent years, the first genus of presumed head lice on trogons worldwide, and the fifth genus of chewing lice known from trogons globally. A translated and revised key to the Philopterus-complex is provided, as well as notes on the various chewing lice genera known from trogons. Keywords Phthiraptera · Philopteridae · Philopterus-complex · Trogoniformes · New genus · New species Introduction The relationships between many species in the Philop- terus-complex are poorly known, and most species are today Lice in the Philopterus-complex are specialized for life placed in the large and heterogeneous genus Philopterus on the heads of their hosts [1, 2].